One afternoon, in a small window of time between when my students departed at the end of another two-week block course and my turning of attention to report writing, I spent a few moments reflecting on the mysterious relationship between what we ecclesiastical types call ‘call’ and the ancient (its origins were in the 5th century) Feast of the Annunciation – that much-downplayed event in the church’s calendar set to mark the archangel Gabriel’s announcement to Mary that she would conceive and become theotokos (God-bearer), and Mary’s fiat, her ready reception of this most inconceivable of happenings.

One thing that struck me was that this feast, which is observed on 25 March – a full term before the celebration of ‘the birth’ – coincides with Good Friday during those seasons when Holy Week happens in March. This not to be glossed over. For the real subject of the Feast is none other than he who was, at least according to one modern translation of the Bible, ‘slain from the creation of the world’ (Rev 13.8). The entirety of human history, in other words, has a distinct mark of the pietà about it, of the fragile God given into human hands. And there is something peculiarly cataclysmic too about 25 March: according to tradition, events as diverse as the creation of the earth, the creation of Adam, Lucifer’s fall, and the crossing of the Red Sea are all supposed to have happened on this date. And yet, none of these events are as significant to the church as the broadcast to a young girl that she is to bear in her womb the very one in whom, by whom and for whom all things exist. Her womb becomes the place where all life, all that will be, is born. Her womb is also the place where she will feel the pain of her son’s death at the hands of violent strangers, and the pain of lifelessness as he who once suckled on her warm breasts in now laid in a cold rock-hewn tomb belonging to some Sanhedrin member from Arimathea.

A further thing that struck me was the way in which this Feast trumpets Christian ministry’s most basic confession; namely, its impossibility – impossibility marked by the unrelenting command to witness to the sheer givenness of God’s unexpected and messy irruption among us and in us. That Christian ministry and theology, as Valdir Steuernagel has it, is ‘born in the guts, twisted by the shock of God’s visit’, and that ‘the cradle of theology is stupefaction, when we find ourselves absolutely lost and completely thankful for God’s visit’, is not the stuff of carefully manufactured and controlled environments. To offer one’s womb so that the life of another might be formed in us, to embrace waiting, to receive the burden of vocation along with others – others who, like cousin Elizabeth, help us to carry on – is to feel ‘pulled into God’s history’. And to be drowned in baptism (sometimes called ‘ordination’) is to discover oneself a character in the divine humour, the early gurglings of him who will have the last laugh. The Feast of the Annunciation is the church’s answer to those who refute that laughter, and the claim that vocations born of Yes’s like Mary’s are marked above all else by anything other than extreme ambiguity.

Most of my window, however, was spent reading and thinking with three poems on the annunciation – one by the Irish poet-priest John O’Donohue, one by the well-known English poet Elizabeth Jennings, and one by the great Welsh poet-priest R. S. Thomas – poems I wanted to share with readers here.

Cast from afar before the stones were born

Cast from afar before the stones were born

And rain had rinsed the darkness for colour,

The words have waited for the hunger in her

To become the silence where they could form.

The day’s last light frames her by the window,

A young woman with distance in her gaze,

She could never imagine the surprise

That is hovering over her life now.

The sentence awakens like a raven,

Fluttering and dark, opening her heart

To nest the voice that first whispered the earth

From dream into wind, stone, sky and ocean.

She offers to mother the shadow’s child;

Her untouched life becoming wild inside.

– John O’Donohue, ‘The Annunciation’, in Conamara Blues (London: Bantom Books, 2001), 61.

≈≈≈

Nothing will ease the pain to come

Nothing will ease the pain to come

Though now she sits in ecstasy

And lets it have its way with her.

The angel’s shadow in the room

Is lightly lifted as if he

Had never terrified her there.

The furniture again returns

To its old simple state. She can

Take comfort from the things she knows

Though in her heart new loving burns

Something she never gave to man

Or god before, and this god grows

Most like a man. She wonders how

To pray at all, what thanks to give

And whom to give them to. “Alone

To all men’s eyes I now must go”

She thinks, “And by myself must live

With a strange child that is my own.”

So from her ecstasy she moves

And turns to human things at last

(Announcing angels set aside).

It is a human child she loves

Though a god stirs beneath her breast

And great salvations grip her side.

– Elizabeth Jennings, ‘The Annunciation’, in Collected Poems (Manchester/New York: Carcanet Press, 1986), 45–46.

≈≈≈

She came like a saint

She came like a saint

to her bride-bed, hands

clasped, mind clenched

on a promise. ‘Some

fell by the wayside,’

she whispered. ‘Come, birds,

winnow the seed lest

standing beside a chaste

cradle with a star

over it, I see flesh

as snow fallen and think

myself mother of God.’

– R. S. Thomas, ‘Annunciation’, in Collected Later Poems, 1988–2000 (Highgreen: Bloodaxe, 2004), 194.

≈≈≈

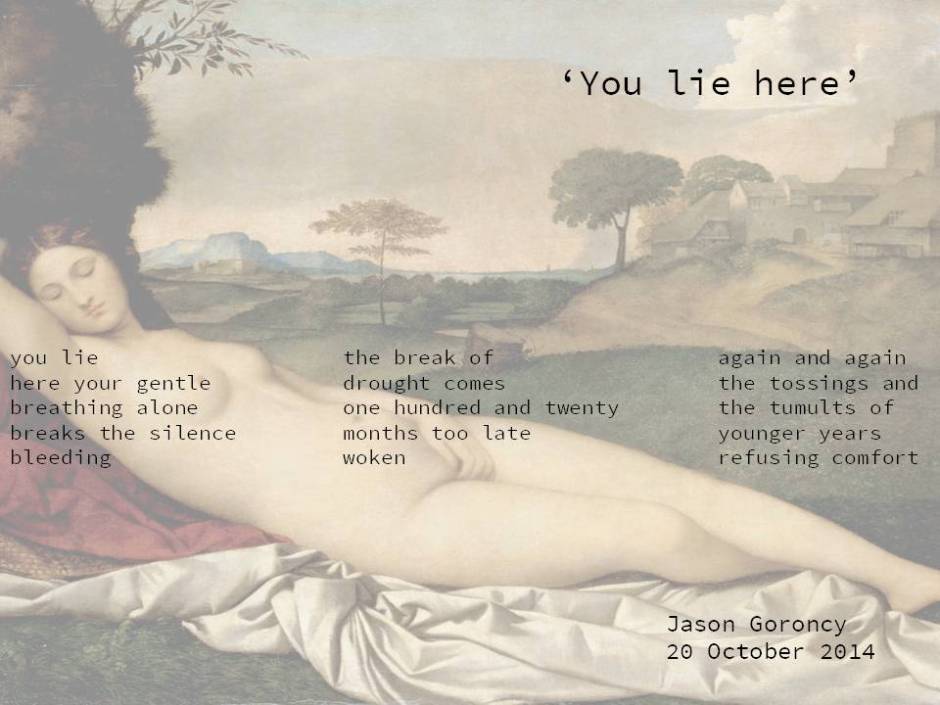

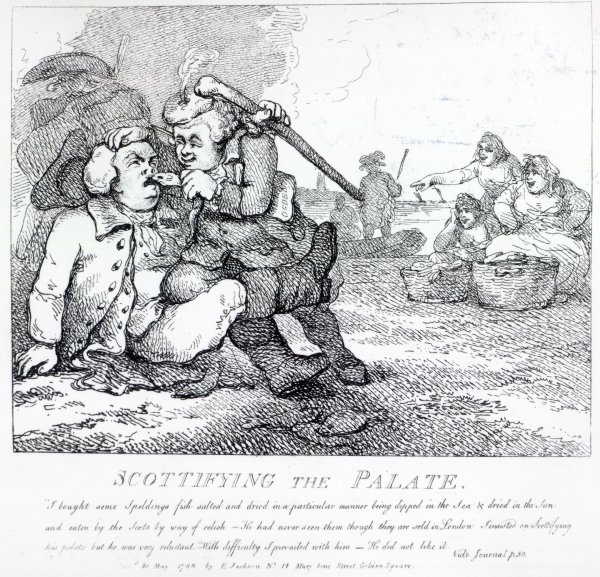

[Image: Duane Michals, ‘The Annunciation, 6/25’. Gelatin Silver Print, 8 x 10 in. Source]

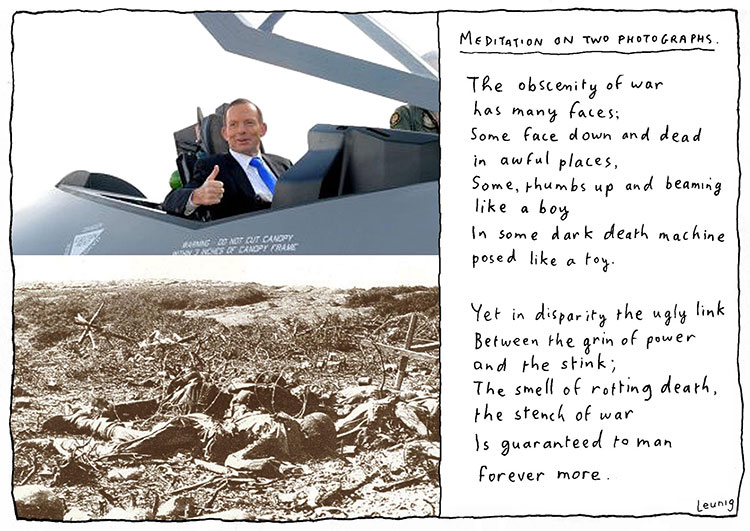

John Milne, who is no stranger to this blog, has recently produced two new choral pieces, both anti-war in theme.

John Milne, who is no stranger to this blog, has recently produced two new choral pieces, both anti-war in theme. The second piece is ‘Still Falls the Rain’. The text here is provided by Edith Sitwell, and cites scripture, ‘Faust’, and all sorts of arcana. Sitwell endured a night of the Blitz in London in 1940, and it is believed that she wrote the poem as the sun rose, bringing with it life’s announcement of perseverance and graced permanence (the Germans bombed exclusively at night). While nowadays we seem to accept with little protest the faceless and mechanised bombing of civilian populations as commonplace, the Blitz marked the first time it was ever done in earnest, and it must have seemed unspeakably vile. John Milne described the closing lines of the poem as ‘as powerful an affirmation of God’s enduring love in the face of near-infinite human evil as I’ve ever encountered’. Those interested in reading further about the poem can read the exegesis provided by Robin Bates, a professor of English at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

The second piece is ‘Still Falls the Rain’. The text here is provided by Edith Sitwell, and cites scripture, ‘Faust’, and all sorts of arcana. Sitwell endured a night of the Blitz in London in 1940, and it is believed that she wrote the poem as the sun rose, bringing with it life’s announcement of perseverance and graced permanence (the Germans bombed exclusively at night). While nowadays we seem to accept with little protest the faceless and mechanised bombing of civilian populations as commonplace, the Blitz marked the first time it was ever done in earnest, and it must have seemed unspeakably vile. John Milne described the closing lines of the poem as ‘as powerful an affirmation of God’s enduring love in the face of near-infinite human evil as I’ve ever encountered’. Those interested in reading further about the poem can read the exegesis provided by Robin Bates, a professor of English at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

These words were written in the 1930s, in response to a photograph accompanying a newspaper article on the Spanish Civil War. Like much of Read’s writing, they could have been written this week or, indeed, in any week since the third century BCE, when the first paper lanterns were created. This is part of their enduring power. But what most strikes me about Read’s poem is the contrast between the violence and loss described in the first three stanzas and the order and reclamation – the being ‘laid out in ranks’ – spoken of in the final one: the mocking plastering-over of violence blasphemously championed under the pretext of bringing order to chaos.

These words were written in the 1930s, in response to a photograph accompanying a newspaper article on the Spanish Civil War. Like much of Read’s writing, they could have been written this week or, indeed, in any week since the third century BCE, when the first paper lanterns were created. This is part of their enduring power. But what most strikes me about Read’s poem is the contrast between the violence and loss described in the first three stanzas and the order and reclamation – the being ‘laid out in ranks’ – spoken of in the final one: the mocking plastering-over of violence blasphemously championed under the pretext of bringing order to chaos.