‘And the angel said to them,

‘And the angel said to them,

“Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you Good News of a great joy that will come to all the people: for to you is born this day in the city oft David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord. And this will be a sign for you: you will find a babe wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger” ( Luke 2:10–12).

On Christmas night the shepherds are addressed by an angel who shines upon them with the blinding glory of God, and they are very much afraid. The tremendous, unearthly radiance shows that the angel is a messenger of heaven and clothes him with an incontrovertible authority. With this authority he commands them not to be afraid but to embrace the great joy he is announcing to them. And while the angel is speaking thus to these poor frightened people, he is joined by a vast number of others, who unite in a “Gloria” praising God in heaven’s heights and announcing the peace of God’s goodwill to men on earth. Then, we read, “the angels went away from them into heaven.” In all probability the singing was very beautiful and the shepherds were glad to listen; doubtless they were sorry when the concert was over and the performers disappeared behind heaven’s curtain. Probably, however, they were secretly a little relieved when the unwonted light of divine glory and the unwonted sound of heavenly music came to an end, and they found themselves once more in their familiar earthly darkness. They probably felt like shabby beggars who had suddenly been set in a king’s audience chamber among courtiers dressed in magnificent robes and were glad to slip away unnoticed and take to their heels.

But the strange thing is that the intimidating glory of the heavenly realm, which has now vanished, has left behind a human glow of joy in their souls, a light of joyous expectation, reinforcing the heavenward-pointing angel’s word and causing them to set out for Bethlehem. Now they can turn their backs on the whole epiphany of the heavenly glory �for it was only a starting point, an initial spark, a stimulus leading to what was really intended; all that remains of it is the tiny seed of the word that has been implanted in their hearts and that now starts to grow in the form of expectation, curiosity and hope: “Let us go over to Bethlehem and see this thing that has happened, which the Lord has made known to us.” They want to see the word that has taken place. Not the angel’s word with its heavenly radiance: that has already become unimportant. They want to see the content of the angel’s word, that is, the Child, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. They want to see the word that has “happened”, the word that has taken place, the word that is not only something uttered but something done, something that can not only be heard but also seen.

Thus the word that the shepherds want to see is not the angel’s word. This was only the proclamation (the kerygma, as people say nowadays); it was only a pointer. The angels, with their heavenly authority, disappear: they belong to the heavenly realm; all that remains is a pointer to a word that has been done. By God, of course. Just as it is God who made it known to them through the angels.

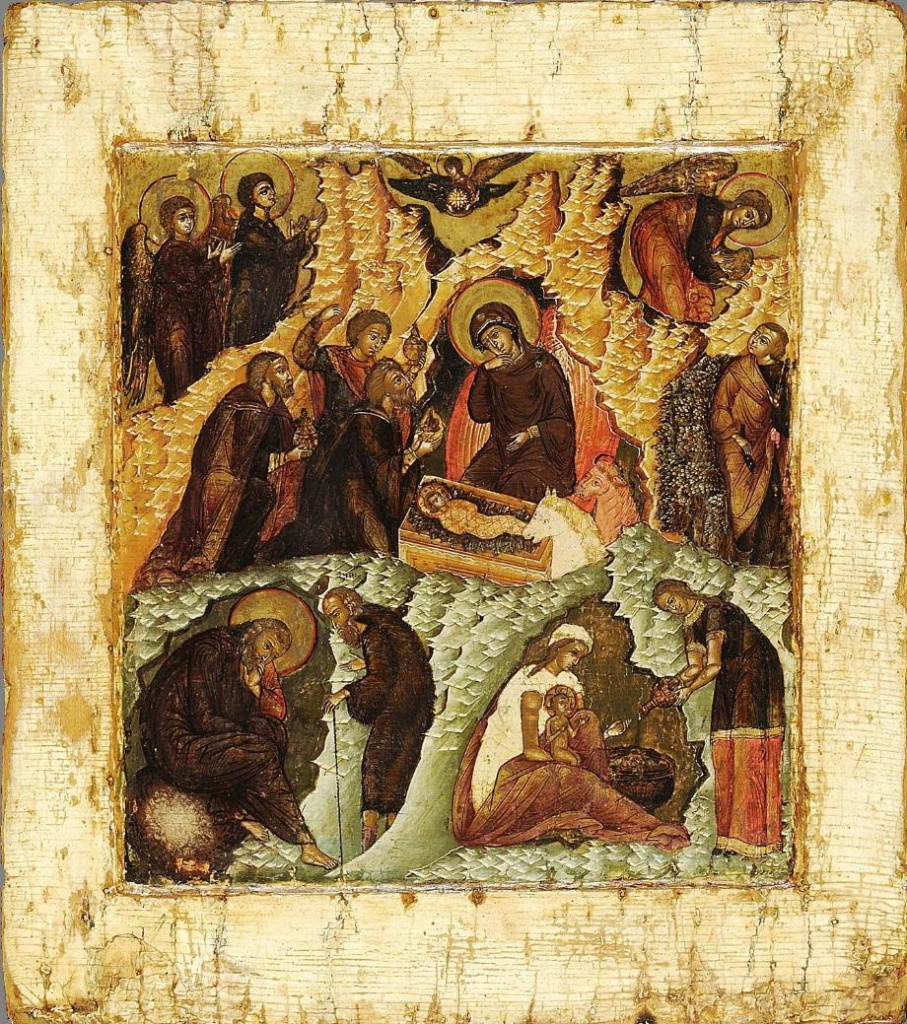

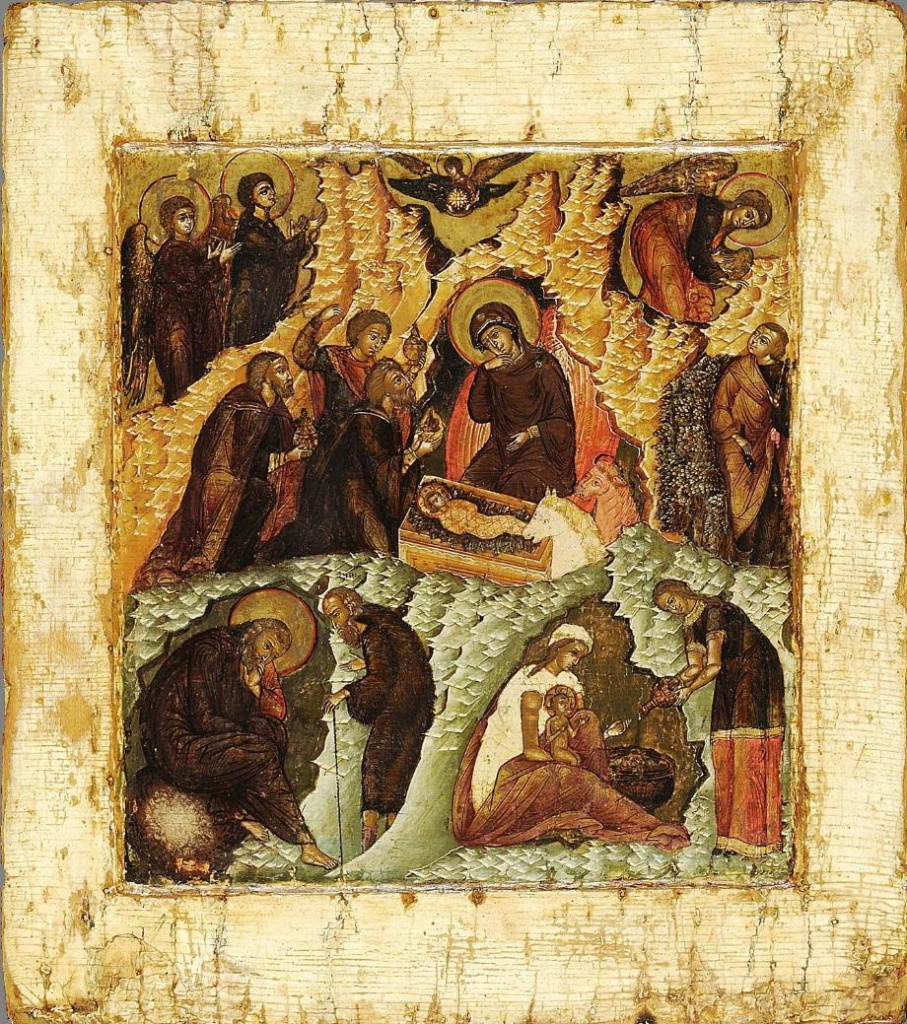

So they set off, heaven behind them, and the earthly sign before them. But, Lord, what a sign! Not even the Child, but a child. Some child or other. No special child. Not a child radiating a light of glory, as the religious painters depicted, but on the contrary: a child that looks as inglorious as possible. Wrapped in swaddling clothes. So that it cannot move. It lies there, imprisoned, as it were, in the clothes in which it has been wrapped through the solicitude of others. There is nothing elevating about the manger in which it lies, either, nothing even remotely corresponding to the heavenly glory of the singing angels. There is practically nothing even half worth seeing; the destination of the shepherds’ nightly journey is the most ordinary scene. Indeed, in its poverty it is decidedly disappointing. It is something entirely human and ordinary, something quite profane, in no way distinguished�except for the fact that this is the promised sign, and it fits.

The shepherds believe the word. The word sends them from heaven and to earth, and as they proceed along this path, from light to darkness, from the extraordinary to the ordinary, from the solitary experience of God to the realm of ordinary human intercourse, from the splendor above to the poverty below, they are given the confirmation they need: the sign fits. Only now does their fearful joy under heaven’s radiance turn into a completely uninhibited, human and Christian joy. Because it fits. And why does it fit? Because the Lord, the High God, has taken the same path as they have: he has left his glory behind him and gone into the dark world, into the child’s apparent insignificance, into the unfreedom of human restrictions and bonds, into the poverty of the crib. This is the Word in action, and as yet the shepherds do not know, no one knows, how far down into the darkness this Word-in-action will lead. At all events it will descend much deeper than anyone else into what is worldly, apparently insignificant and profane; into what is bound, poor and powerless; so much so that we shall not be able to follow the last stage of his path. A heavy stone will block the way, preventing the others from approaching, while, in titter night, in ultimate loneliness and forsakenness, he descends to his dead human brothers.

It is true, therefore: in order that he shall find God, the Christian is placed on the streets of the world, sent to his manacled and poor brethren, to all who suffer, hunger and thirst; to all who are naked, sick and in prison. From henceforth this is his place; he must identify with them all. This is the great joy that is proclaimed to him today, for it is the same way that God sent a Savior to us. We ourselves may be poor and in bondage too, in need of liberation; yet at the same time all of us who have been given a share in the joy of deliverance are sent to be companions of those who are poor and in bondage.

But who will step out along this road that leads from God’s glory to the figure of the poor Child lying in the manger? Not the person who is taking a walk for his own pleasure. He will walk along other paths that are more likely to run in the opposite direction, paths that lead from the misery of his own existence toward some imaginary or dreamed-up attempt at a heaven, whether of a brief pleasure or of a long oblivion. The only one to journey from heaven, through the world, to the hell of the lost, is he who is aware, deep in his heart, of a mission to do so; such a one obeys a call that is stronger than his own comfort and his resistance. This is a call that has complete power and authority over my life; I submit to it because it comes from a higher plane than my entire existence. It is an appeal to my heart, demanding the investment of my total self; its hidden, magisterial radiance obliges me, willy-nilly, to submit. I may not know who it is that so takes me into his service. But one thing I do know: if l stay locked within myself, if I seek myself, I shall not find the peace that is promised to the man on whom God’s favor rests. I must go. I must enter the service of the poor and imprisoned. I must lose my soul if I am to regain it, for so long as I hold onto it, I shall lose it. This implacable, silent word (which yet is so unmistakable) burns in my heart and will not leave me in peace.

In other lands there are millions who are starving, who work themselves to death for a derisory day’s wage, heartlessly exploited like cattle. There too are the slaughtered peoples whose wars cannot end because certain interests (which are not theirs) are tied up with the continuance of their misery. And I know that all my talk about progress and mankind’s liberation will be dismissed with laughter and mockery by all the realistic forecasters of mankind’s next few decades. Indeed, I only need to open my eyes and ears, and I shall hear the cry of those unjustly oppressed growing louder every day, along with the clamor of those who are resolved to gain power at any price, through hatred and annihilation. These are the superpowers of darkness; in the face of them all our courage drains away, and we lose all belief in the mission that resides in our hearts, that mission that was once so bright, joyous and peace bringing; we lose all hope of really finding the poor Child wrapped in swaddling clothes. What can my pitiful mission achieve, this drop of water in the white-hot furnace? What is the point of my efforts, my dedication, my sacrifice, my pleading to God for a world that is resolved to perish?

“Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you Good News of a great joy … This day is born the Savior”, that is, he who, as Son of God and Son of the Father, has traveled (in obedience to the Father) the path that leads away from the Father and into the darkness of the world. Behind him omnipotence and freedom; before, powerlessness, bonds and obedience. Behind him the comprehensive divine vision; before him the prospect of the meaninglessness of death on the Cross between two criminals, Behind him the bliss of life with the Father; before him, grievous solidarity with all who do not know the Father, do not want to know him and deny his existence. Rejoice then, for God himself has passed this way! The Son took with him the awareness of doing the Father’s will. He took with him the unceasing prayer that the Father’s will would be done on the dark earth as in the brightness of heaven. He took with him his rejoicing that the Father had hidden these things from the wise and revealed them to babes, to the simple and the poor. “I am the way”, and this way is “the truth” for you; along this way you will find “the life”. Along “the way” that I am you will learn to lose your life in order to find it; you will learn to grow beyond yourselves and your insincerity into a truth that is greater than you are. From a worldly point of view everything may seem very dark; your dedication may seem unproductive and a failure. But do not be afraid: you are on God’s path. “Let not your hearts be troubled: believe in God; believe also in me.” I am walking on ahead of you and blazing the trail of Christian love for you. It leads to your most inaccessible brother, the person most forsaken by God. But it is the path of divine love itself. You are on the right path. All who deny themselves in order to carry out love’s commission are on the right path.

Miracles happen along this path. Apparently insignificant miracles, noticed by hardly anyone. The very finding of a Child wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger �is this not a miracle in itself? Then there is the miracle when a particular mission, hidden in a person’s heart, really reaches its goal, bringing God’s peace and joy where there were nothing but despair and resignation; when someone succeeds in striking a tiny light in the midst of an overpowering darkness. When joy irradiates a heart that no longer dared to believe in it. Now and again we ourselves are assured that the angel’s word we are trying to obey will bring us to the place where God’s Word and Son is already made man. We are assured that, in spite of all the noise and nonsense, today, December 25, is Christmas just as truly as two millennia ago. Once and for all God has started out on his journey toward us, and nothing, till the world’s end, will stop him from coming to us and abiding in us’.

– Hans Urs von Balthasar, ‘Setting Out into the Dark with God’, in You Crown the Year With Your Goodness: Sermons Throughout the Liturgical Year (Ignatius Press, 1989).

… in the previous

… in the previous  An old song of the music hall

An old song of the music hall