A few days before the recent leadership spill in the Australian Labor Party, former Cabinet Minister and (in my view, quite exceptional) Foreign Minister Gareth Evans offered some thoughts, or some evidence of ‘relevance deprivation syndrome’, on the ALP and what we all might be able to learn from Australia’s political meltdown. I thought them worth reposting:

Australian politics should, on the face of it, hold as much interest for the rest of the world as Mongolian throat singing or Bantu funerary rites. But I have found otherwise in my recent travels in North America, Europe, and Asia. Much more than one might expect, there is an eerie fascination in political and media circles with the death throes of the current Australian Labor Party (ALP) government.

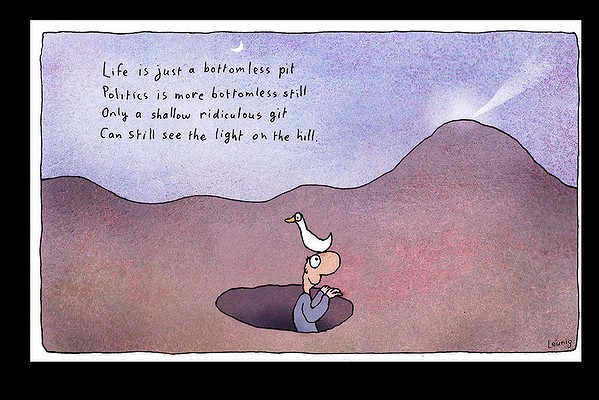

How is it, policymakers and analysts ask, that a government that steered Australia comfortably through the global financial crisis, and that has presided for the last six years over a period of almost unprecedented prosperity, could be facing electoral extinction in September, as every opinion poll is now predicting?

How did a diverse, socially tolerant country with living standards that are the envy of much of the world, become roiled by so much political divisiveness and bitterness? Is there a message for democratic governments generally, or center-left governments elsewhere, or just for the ALP?

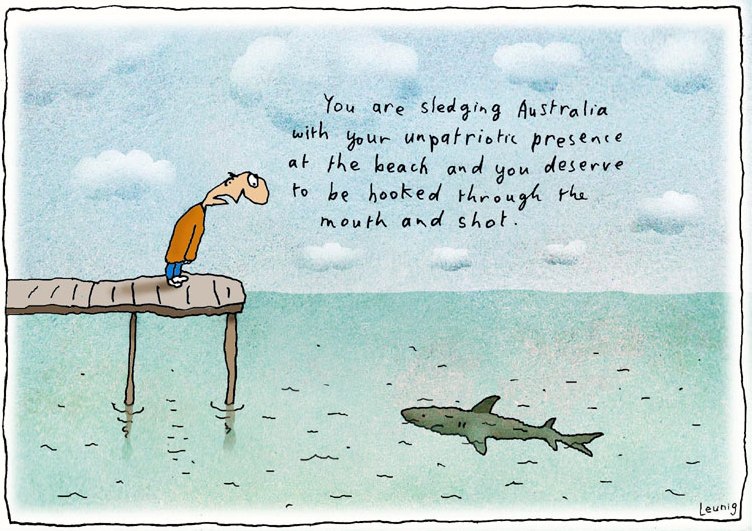

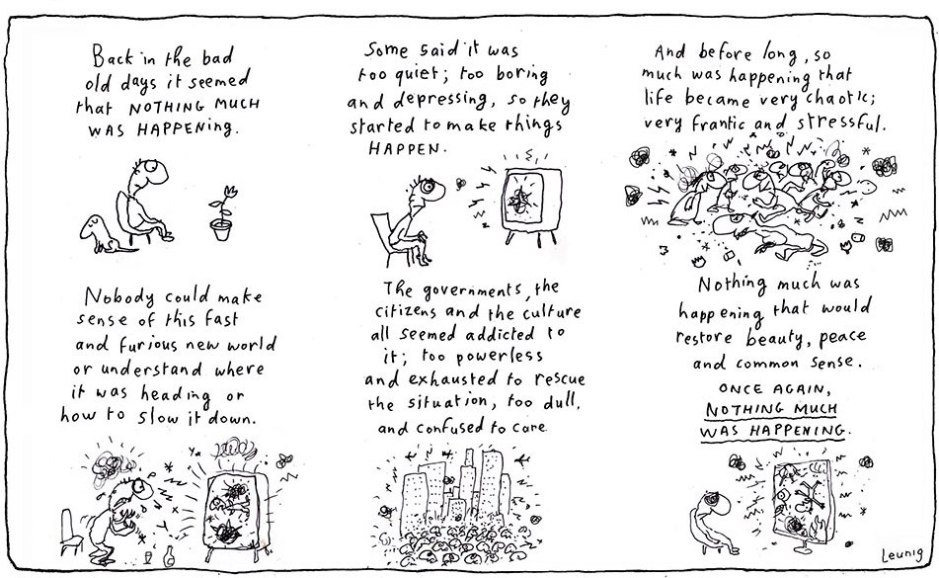

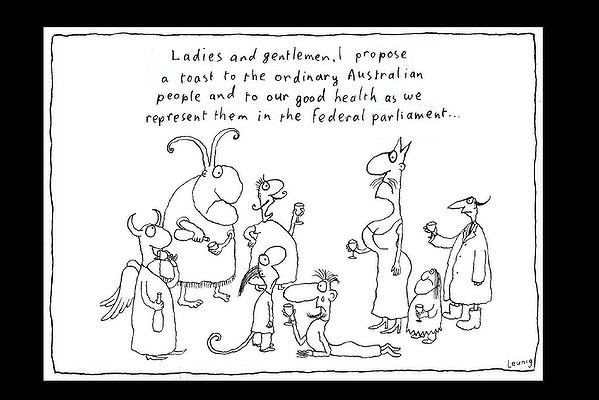

It may be that certain peculiarities of the Australian situation are creating more tensions than would be likely elsewhere. A ludicrously short three-year electoral cycle makes it almost impossible to govern in a campaign-free atmosphere. Party rules allow for leaders – including serving prime ministers – to be politically executed overnight by their parliamentary colleagues. Our media’s preoccupation with trivia – and collective lack of conscience – is impressive even by British tabloid standards.

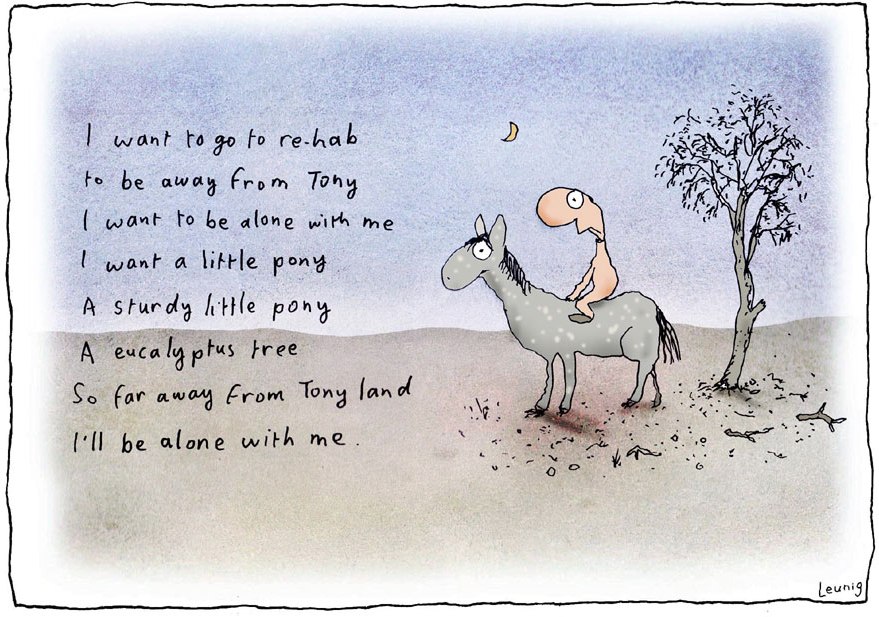

But none of these factors is new. They might have compounded the tensions, but they don’t explain how, in 2010, a party less than three years into its term dispatched a leader, Kevin Rudd, who had brought it to power after 11 years in the political wilderness and still commanded a majority of the public’s support. Nor do they explain why now, three years after she replaced Rudd, Julia Gillard enjoys practically no public support at all and seems destined to lead the ALP back into exile for another generation, if not for good.

Even if Gillard is dropped by her panicking colleagues – and that could happen at any time in the Grand Guignol theater that Australian politics has become – the situation for the world’s oldest labor party is dire indeed.

Those like me who have been out of public office for a long time need to be wary about offering gratuitous commentary – or, worse, advice. It is unlikely to be gratefully received by one’s successors, and it suggests a severe case of what I call “relevance deprivation syndrome.”

But there do seem to be some fundamental rules of political survival that have been ignored in Australia in recent years. Perhaps spelling them out will help others to remember them, not least those parties in Europe, Canada, and elsewhere that share some of the ALP’s social-democratic and center-left ideological traditions and are also struggling to win or retain electoral support.

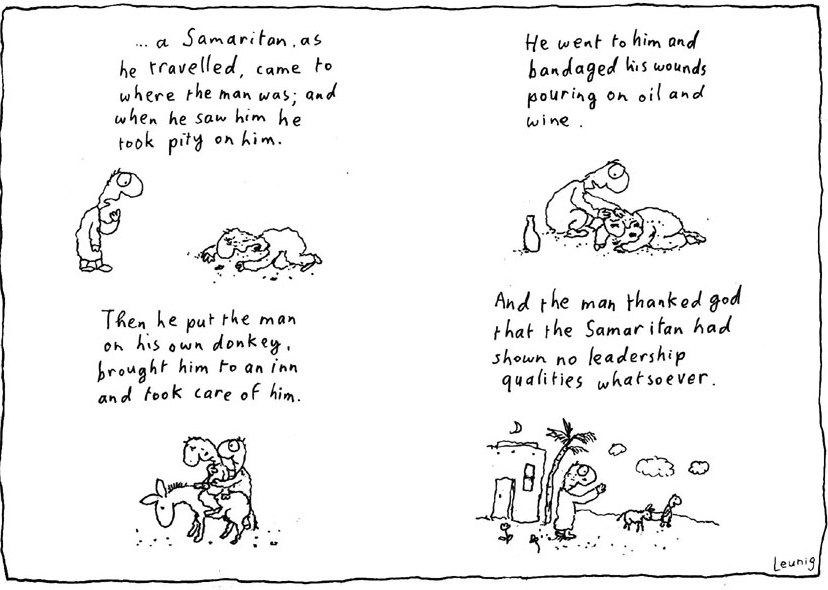

The first rule is to have a philosophy – and to stick to it. The hugely successful Labor governments led by Bob Hawke and Paul Keating two decades ago did just that, essentially inventing the “third way” model that later became associated with Tony Blair and Gordon Brown in Britain. Its elements were clear: dry, free-market economics (but in our case with low-paid workers benefiting enormously from “social wage” increases in medical care and retirement pensions); compassionate social policy; and a liberal internationalist foreign policy.

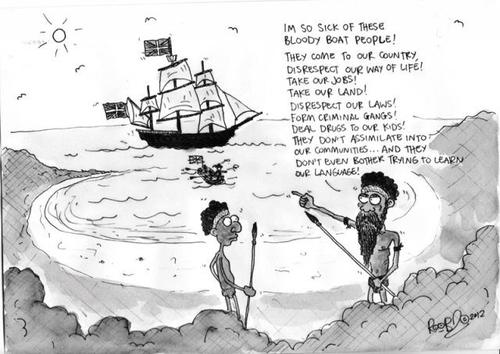

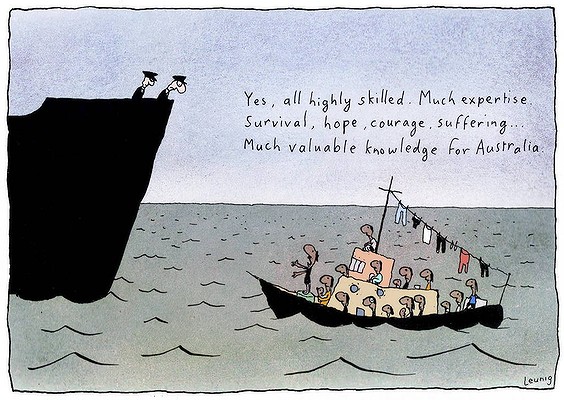

Australia’s current government, by contrast, has struggled to re-create anything as compelling. It seems torn between old industrial labor preoccupations, the new environmentalism, and capitulating to populist anxiety on issues like asylum-seeking “boat people.”

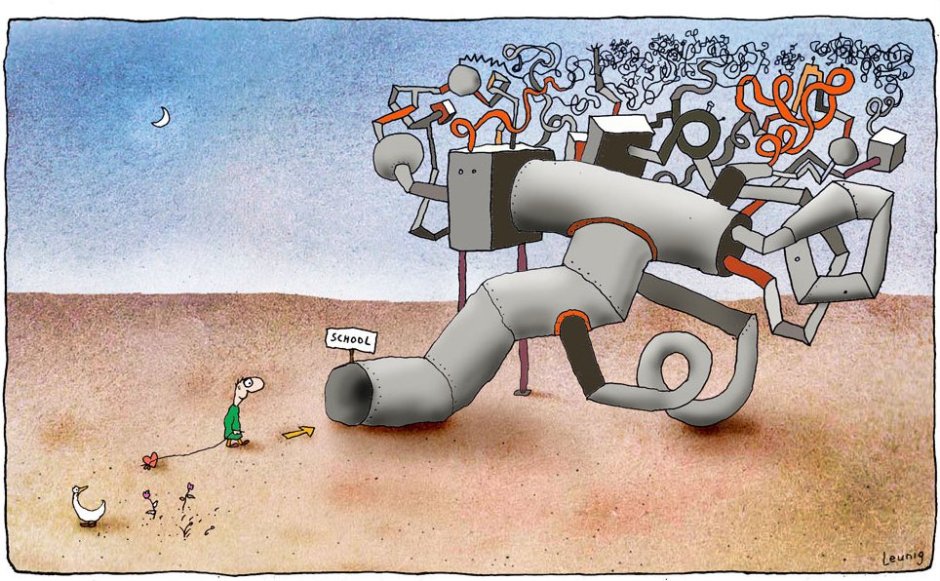

The second rule is to have a narrative – and to stick to it. Confused and ever-changing messages don’t win votes. The most wounding criticism of the ALP government is that no one really knows what it stands for. It has initiated visionary national policies in areas like broadband access, disability support, and education, but it has struggled to maintain a coherent and consistent overall story line.

The third rule is to have a decent governing process – and to stick to it. The Rudd administration successfully navigated the global financial crisis largely because the prime minister, with a small inner group, bypassed traditional Cabinet processes. But, with the crisis over, the bypassing continued – increasingly by the prime minister alone. Genuinely collective decision-making can be a painfully difficult process, but, in government as elsewhere, there is wisdom in crowds.

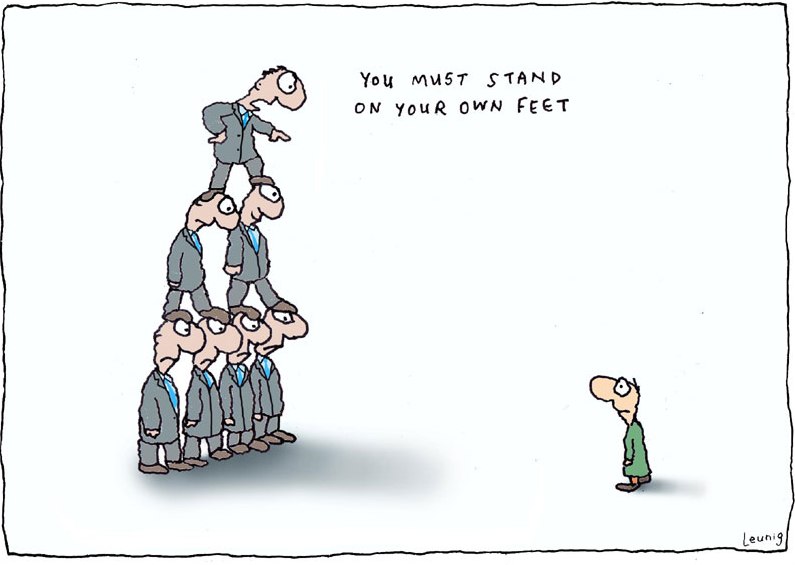

The fourth rule is that leaders should surround themselves with well-weathered colleagues and advisers who will remind them, as often as necessary, of their mortality. Self-confidence, bordering on hubris, gets most leaders to the top. If that is not occasionally punctured, things are bound to end in tears.

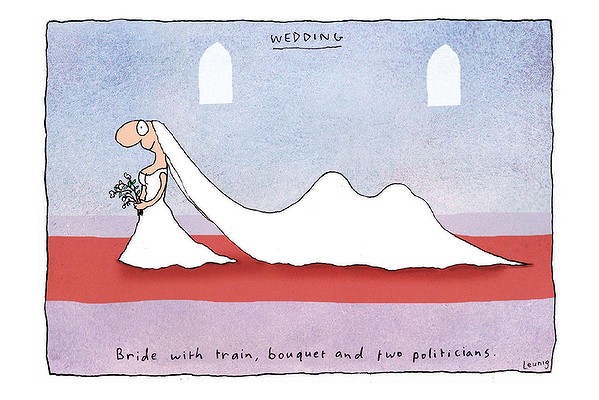

The last rule is that one should never trash the brand. Those who mounted the coup against Rudd three years ago felt it necessary to explain that it was because his government was, beneath the surface, a dysfunctional mess. The public hadn’t actually noticed that at the time, but has been prepared to believe it ever since. The tragedy is that both Rudd and Gillard are superbly capable and have complementary skill sets; working together effectively, they were as good as it gets in Australian politics.

Adherence to these rules will not ensure that a governing party stays in office forever. Many other factors, domestic and international, are always in play. Over time, electorates will tire of even the best-run governments, and look for reasons to vote for change.

But following all of these rules should ensure that a party maintains credibility and respect, and that, in defeat, it at least remains competitive for the next election. Observing none of them guarantees catastrophe.