It is impossible, it seems, for a theologian to think seriously about the arts and not before long be confronted with the question of visual representations of God and, for the Christian theologian, of God as incarnate. The Orthodox and the Reformed traditions, in particular, have long taken this question with the utmost seriousness (and that beside heated debates on the communicatio idiomatum or of those on the question of Christ’s presence in the Supper). The four main objections seem to be:

It is impossible, it seems, for a theologian to think seriously about the arts and not before long be confronted with the question of visual representations of God and, for the Christian theologian, of God as incarnate. The Orthodox and the Reformed traditions, in particular, have long taken this question with the utmost seriousness (and that beside heated debates on the communicatio idiomatum or of those on the question of Christ’s presence in the Supper). The four main objections seem to be:

# 1. Violation of the second commandment

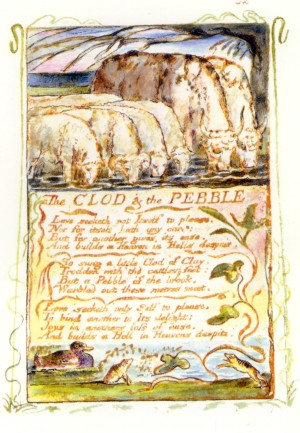

There are no commands to make pictures of our Lord. In fact such pictures, it is argued, clearly violate the second commandment. There are issues here of the ongoing question of idolatry, witnessed to in the Old Testament’s depiction of pagan idols described as being made of gold, silver, wood, and stone – i.e. of the ‘stuff’ of creation, of the work of human hands, unable to speak, see, hear, smell, eat, grasp, or feel, and powerless either to injure or to benefit (Ps 135:15–18). And, of course, there is the Decalogue’s second commandment:

‘You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth’. (Exodus 20:3–4)

Does this commandment put a fence around what artists can – and cannot – depict of God? Are images of Jesus – whether in Sunday School books, galleries, or spaces dedicated for public worship – idolatry? And if not, then how ought we understand the relation between the unique and unrepeatable revelation of God in the incarnation (and that attested to in the inscripturated word and from the Church’s pulpit, font and table) and visual depictions of that Word?

# 2. All attempts are false representations

Since no accurate representation of Christ can be produced by creatures, all attempts are false representations and can only promote idolatry.

# 3. We don’t know what Jesus looks like

Despite passages like Isaiah 53:2 and Revelation 1:13–16, the Bible does not give us enough information to make a faithful representation of Christ’s physical appearance. Therefore, it is obvious that God does not sanction portraits of God’s Son.

# 4. All plastic (i.e. material) representations of Jesus implicitly promote the ancient heresy of Nestorianism

# 4. All plastic (i.e. material) representations of Jesus implicitly promote the ancient heresy of Nestorianism

The most serious objection to artists’ attempts to represent Jesus pictorially has been associated with this charge of Nestorianism. In other words, even if we had a photo of Jesus which depicted what he looked like, no human artistry can portray Christ’s divine nature. Therefore, all attempts are a lie and portray Jesus as infinitely less, or other, than he is as the God-human. This argument was proposed by the Council of Constantinople in 754:

‘If any person shall divide human nature, united to the Person of God the Word; and, having it only in the imagination of his mind, shall therefore, attempt to paint the same in an Image; let him be holden as accursed. If any person shall divide Christ, being but one, into two persons; placing on the one side the Son of God, and on the other side the son of Mary; neither doth confess the continual union that is made; and by that reason doth paint in an Image of the son of Mary, as subsisting by himself; let him be accursed. If any person shall paint in an Image the human nature, being deified by the uniting thereof to God the Word; separating the same as it were from the Godhead assumpted and deified; let him be holden as accursed’.

Regarding this council Philip Schaff, in History of the Christian Church. Volume IV: Mediæval Christianity from Gregory I to Gregory VI; A.D. 590–1073, writes:

The council [of Constantinople, 754], appealing to the second commandment and other Scripture passages denouncing idolatry (Rom. 1:23, 25; John 4:24), and opinions of the Fathers (Epiphanius, Eusebius, Gregory Nazianzen, Chrysostom, etc.), condemned and forbade the public and private worship of sacred images on pain of deposition and excommunication … It denounced all religious representations by painter or sculptor as presumptuous, pagan and idolatrous. Those who make pictures of the Saviour, who is God as well as man in one inseparable person, either limit the incomprehensible Godhead to the bounds of created flesh, or confound his two natures, like Eutyches, or separate them, like Nestorius, or deny his Godhead, like Arius; and those who worship such a picture are guilty of the same heresy and blasphemy. The eucharist alone is the proper image of Christ. (pp. 457–8.)

This issue is just one of the many in which the great twentieth-century theologian Karl Barth and his reformation great-grandfather, John Calvin, agree. They both held that:

- Preaching and sacraments are central to the community’s activity;

- That static works are a distraction to the ‘listening community’;

- That the community should not be bound to a particular conception of Jesus;

- That even the best art cannot ‘display Jesus Christ in his truth, i.e., in his unity as true Son of God and Son of Man. There will necessarily be either on the one side, as in the great Italians, an abstract and docetic over-emphasis on His deity, or on the other, as in Rembrandt, an equally abstract, ebionite over-emphasis on His humanity, so that even with the best of intentions error will be promoted’ (Barth, CD IV.3.2, 867). To be sure, Barth had already anticipated this move in CD IV.2 when he insisted that Jesus Christ cannot be known in his humanity as abstracted from his divine sonship. See CD IV.2, 102–3.

- ‘Whatever [people] learn of God in images is futile’ (Calvin, Institutes, I.xi.5). God’s majesty ‘is far above the perception of our eyes … Even if the use of images contained nothing evil, it still has no value for teaching’ (Inst., I.xi.12); and

- ‘Theology cannot fix upon, consider, and put into words any truths which rest on or are moved by themselves – neither an abstract truth about God nor about man nor about the intercourse between God and man. It can never verify, reflect or report in a monologue. Incidentally, let it be said that there is no theological visual art. Since it is an event, the humanity of God does not permit itself to be fixed in an image’ (Barth, The Humanity of God, 57).

That art is concerned with ‘earthly, creaturely things’ is reflected in Karl Barth’s scathing critique of attempts to visualise the ‘inaccessible and incomprehensible side of the created world’, and he lists ‘heaven’, and Christ’s resurrection and ascension as examples: ‘There is no sense in trying to visualise the ascension as a literal event, like going up in a balloon. The achievements of Christian art in this field are amongst its worst perpetrations’ (CD III.2, 453). And, on the resurrection, he writes:

That art is concerned with ‘earthly, creaturely things’ is reflected in Karl Barth’s scathing critique of attempts to visualise the ‘inaccessible and incomprehensible side of the created world’, and he lists ‘heaven’, and Christ’s resurrection and ascension as examples: ‘There is no sense in trying to visualise the ascension as a literal event, like going up in a balloon. The achievements of Christian art in this field are amongst its worst perpetrations’ (CD III.2, 453). And, on the resurrection, he writes:

There is something else, however, which the Easter records and the whole of the New Testament say but wisely do not describe. In the appearances He not only came from death, but from His awakening from the dead. The New Testament almost always puts it in this way: “from the dead.” From the innumerable host of the dead this one man, who was the Son of God, was summoned and awakened and reconstituted as a living man, the same man as He had been before. This second thing which the New Testament declares but never attempts to describe is the decisive factor. What was there actually to describe? God awakened Him and so He “rose again.” If only Christian art had refrained from the attempt to depict it! He comes from this event which cannot be described or represented – that God awakened Him. (Barth, CD IV.2, 152)

While Barth and Calvin could and did find proper recognition of the gift of God’s love expressed in human culture, they both failed to find in their theology a positive place for the plastic arts that they could find, for example, in music. Ah Wolfgang!

So what ought we make of Barth’s – and others (e.g. Calvin, Kierkegaard) – judgement against visual representations of Jesus? Are visual representations of Jesus really any more susceptible than words (poetry, sermons, etc) about Jesus? (One recalls here Calvin’s insistence that it is the heart that is factory of idols.) Does not God’s act of redeeming creation not extend to the arts’ service of giving an account to the creatureliness of God in Jesus Christ? Does Barth’s and Calvin’s rejection misunderstand the nature of the dynamic and continuing event which is the relationship of the viewer of a painting or a sculpture with the artwork, and of the freedom of the Word in that event? (See Michael Austin, Explorations in Art, Theology and Imagination, 21.)

For most of the Reformed, theology is something that is meant to be done with words, and not with images. But, of course, every decision we make about how we choose to communicate the good news is loaded with visual symbolism and reinforces a perception that God communicates with us in a particular kind of way. The question, therefore, is not, whether or not we should communicate visually; it is, rather, how we do so and what we say when we do.

One of the things that good art does is to shed light on the true nature of things; it broadens our horizons, enriches our capacity to see, alerts us to dimensions of reality that we had not seen before, and for which words, sometimes, are simply not enough. The arts help us to birth the kind of imagination and re-imagination that the good news itself fosters and encourages and demands and makes and invites. Artists see differently, but no less truthfully than scientists, how things are with the world. If we are to walk in our world well, and justly and with the mercy of God, then we cannot do so without the kind of re-imagining of reality and of human society that the arts promote and invite.

So NT Wright:

So NT Wright:

‘We have lived for too long with the arts as the pretty bit around the edge with the reality as a non-artistic thing in the middle. But the world is charged with the grandeur of God. Why should we not celebrate and rejoice in that? And the answer sometimes is because the world is also a messy and nasty and horrible place. And, of course, some artists make a living out of representing the world as a very ugly and wicked and horrible place. And our culture has slid in both directions so that we have got sentimental art on the one hand and brutalist art in the other. And if you want to find sentimental art then, tragically, the church is often a good place to look, as people when they want to paint religious pictures screen out the nasty bits. But genuine art, I believe, takes seriously the fact that the world is full of the glory of God, and that it will be full as the waters cover the sea, and, at present (Rom 8), it is groaning in travail. Genuine art responds to that triple awareness: of what is true (the beauty that is there), of what will be true (the ultimate beauty), and of the pain of the present, and holds them together as the psalms do, and asks why and what and where are we. You can do that in music, and you can do that in painting. And our generation needs us to do that not simply to decorate the gospel but to announce the gospel. Because again and again, when you can do that you open up hermeneutic space for people whose minds are so closed by secularism that they just literally cannot imagine any other way of the world being. I have debated in public in America with colleagues in the New Testament guild who refuse to believe in the bodily resurrection and, again and again, the bottom line is when they say ‘I just can’t imagine that’, the answer is, ‘Smarten up your imagination’. And the way to do that is not to beat them over the head with dogma but so to create a world of mystery and beauty and possibility, that actually there are some pieces of music which when you come out of them it is much easier to say ‘I believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit’ than when you went in’. (NT Wright, ‘Jesus, the Cross and the Power of God’. Conference paper presented at European Leaders’ Conference, Warsaw, February, 2006).

Of course, as Murray Rae recently reminded a bunch of us here in Dunedin, the risk-taking work of re-imagining means that there can be no guarantee that misunderstanding and misinterpretation will be avoided. But neither do we have any such guarantee in the use of our words. In both cases, it seems, what we offer is an act of faith given under God’s imperative that we should share the good news. We offer in Christian witness so much as we have understood, knowing it to be partial, inadequate, and marred by our own sinfulness. And we do so in the name and under the inspiration of the God who makes eloquent the stumbling witness of our faith, and moulds our communication to good and loving purpose. It’s risky, but it is, it seems, God’s risk too.

Perhaps a few words from John de Gruchy would be a fitting way to conclude this post:

Art in itself cannot change society, but good art, whatever its form, helps us both individually and corporately to perceive reality in a new way, and by so doing, it opens up possibilities of transformation. In this way art has the potential to change both our personal and corporate consciousness and perception, challenging perceived reality and enabling us to remember what was best in the past even as it evokes fresh images that serve transformation in the present. This it does through its ability to evoke imagination and wonder, causing us to pause and reflect and thereby opening up the possibility of changing our perception and ultimately our lives … From a Christian perspective, the supreme image that contradicts the inhuman and in doing so becomes the icon of redemption is that of the incarnate, crucified and risen Christ. So it is not surprising that artists through the centuries have sought to represent that alien beauty as a counter to the ugliness of injustice. We are not redeemed by art nor by beauty alone, but by the holy beauty which is revealed in Christ and which, through the Spirit evokes wonder and stirs our imagination. (John W. de Gruchy, ‘Holy Beauty: A Reformed Perspective on Aesthetics Within a World of Ugly Injustice’ in Reformed Theology for the Third Christian Millennium: The 2001 Sprunt Lectures, 14–5).