‘Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.

‘Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.

Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever.

Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never’. (Elie Wiesel. Night, 45).

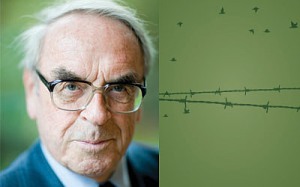

So penned Elie Wiesel in the moving record of his childhood in the death camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. For Wiesel, as for countless others – both inside and outside the camps – the systematic extermination of millions of human beings – whether Jews, political activists, homosexuals, or others – meant the death of faith and of God. In fact, as John de Gruchy perceptively notes in his Theology and Ministry in Context and Crisis: A South African Perspective, ‘suffering is especially a problem for the person who believes, or who wants to believe in God. Yet, paradoxically, the problem can only be handled from the perspective of faith’ (p. 102).

There can be no real argument that ‘suffering is built into the fabric of human existence’ (Ibid., p. 97), and that questions of suffering pose the most real and existentially-alive challenge to belief in God. Suffering, the kind of suffering that ‘plucks the tongue from the head and the voice from the heart’ (Daniel Berrigan in Hans-Ruedi Weber, On a Friday Noon: Meditations Under the Cross, p. 28), is both a challenge and opportunity for Christian belief as well as for pastoral ministry because it is held to demonstrate the logical incoherence of Christianity.

One of the most influential novels of last century was The Plague (1947) by the French-Algerian author, philosopher, and journalist Albert Camus (1913–1960). The Plague recalls a plague (oddly enough) which is causing untold suffering and death, underscoring the universal condition of humankind. Dr Reuss, the main character, a compassionate physician, says at one point, ‘Since … the world is shaped by death mightn’t it be better for God if we refuse to believe in Him and struggle with all our might against death, without raising our eyes toward the heaven where He sits in silence?’ (p. 128.). Elsewhere there is a scene where a priest, an unbeliever and the doctor surround the bed of a little boy who is dying. He suffers in pain. The priest asks God for help: ‘My God, spare this child’ (p. 217). The boy dies. Later the priest declares, ‘That sort of thing is revolting because it passes our human understanding. But perhaps we should love what we cannot understand’. The doctor responds: ‘“No, Father. I’ve a very different idea of love. And until my dying day I shall refuse to love a scheme of things in which children are put to torture”’ (p. 218).

At another time, Camus was returning home from church when a six year old girl asked him why little girls starve in Africa while she has plenty to eat: ‘Doesn’t God love them as much as he does me?’ His inability to provide an answer birthed the conclusion that there was no God. To this, C.S. Lewis may have replied (as he did in The Problem of Pain) that

‘The problem of reconciling human suffering with the existence of a God who loves, is only insoluble so long as we attach a trivial meaning to the word “love”, and look on things as if man were the centre of them. Man is not the centre. God does not exist for the sake of man. Man does not exist for his own sake. “Thou hast created all things, and for thy pleasure they are and were created.” We were made not primarily that we may love God (though we were made for that too) but that God may love us, that we may become objects in which the Divine love may rest “well pleased”. To ask that God’s love should be content with us as we are is to ask that God should cease to be God: because He is what He is, His love must, in the nature of things, be impeded and repelled, by certain stains in our present character, and because He already loves us He must labour to make us lovable’. (p. 36)

On 4 June 1886, T.H. Huxley penned a letter to a Sir John Skelton. The letter concluded with these words: ‘… there is amazingly little evidence of “reverential care for unoffending creation” in the arrangements of nature, that I can discover. If our ears were sharp enough to hear all the cries of pain that are uttered by men and beasts, we should be deafened by one continuous scream! And yet the wealth of superfluous loveliness in the world condemns pessimism. It is a hopeless riddle’ (Leonard Huxley, Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley, in Three Volumes, 2:353). Again, the question of suffering is unquestionably among the most difficult for faith, and so for pastoral ministry. So Jürgen Moltmann in The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God: ‘It is in suffering that the whole human question about God arises … [Suffering] is the open wound of life in this world’ (pp. 47, 49). So too Lance Morrow, in a Time Magazine article entitled ‘Evil’:

‘The historian Jeffrey Burton Russell asks, ‘What kind of God is this? Any decent religion must face the question squarely, and no answer is credible that cannot be given in the presence of dying children’. Can one propose a God who is partly evil? Elie Wiesel, who was in Auschwitz as a child, suggests that perhaps God has ‘retracted himself’ in the matter of evil. Wiesel has written, ‘God is in exile, but every individual, if he strives hard enough, can redeem mankind, and even God himself’’.

This situation is, in Moltmann’s words, ‘the open wound of life’ in which honest pastoral ministry happens. In the post-Auschwitz world, questions of suffering and theodicy have determined, dominated and challenged theology. As Rabbi Richard L. Rubenstein put it in After Auschwitz: History, Theology, and Contemporary Judaism:

‘I believe the greatest single challenge to modern Judaism arises out of the question of God and the death camps. I am amazed at the silence of contemporary Jewish theologians on this most crucial and agonizing of all Jewish issues. How can Jews believe in an omnipotent, beneficent God after Auschwitz? Traditional Jewish theology maintains that God is the ultimate, omnipotent actor in the historical drama. It has interpreted every major catastrophe in Jewish history as God’s punishment of a sinful Israel. I fail to see how this position can be maintained without regarding Hitler and the SS as instruments of God’s will. The agony of European Jewry cannot be likened to the testing of Job. To see any purpose in the death camps, the traditional believer is forced to regard the most demonic, anti-human explosion of all history as a meaningful expression of God’s purposes. The idea is simply too obscene for me to accept’. (p. 171)

And others too have asked:

‘You will sooner or later be confronted by the enigma of God’s action in history’. (Elie Wiesel, in One Generation After, as Cited in Richard L. Rubenstein and John K. Roth, Approaches to Auschwitz: The Holocaust and Its Legacy, p. 327)

‘Given the classical theological positions of both Judaism and Christianity, the fundamental question posed by the Holocaust is not whether the existence of a just, omnipotent God can be reconciled with radical evil. That is a philosophical question. The religious question is the following: Did God use Adolf Hitler and the Nazis as his agents to inflict terrible sufferings and death upon six million Jews, including more than one million children?’ (Ibid., p. 327)

‘The God of Holy Nothingness is ‘omnipresent’, although not in the usual sense meant by theologians. This God resides within destruction. The Holy Nothingness generates this-world and its vicissitudes from out of its own fecund plenitude. Yet, a God so involved in the world and its attendant suffering becomes deeply complicit and can only invite the wrath and enmity of her aggrieved children’. (Zachary Braiterman, (God) after Auschwitz: Tradition and Change in Post-Holocaust Jewish Thought, pp. 99–100)

And Martin Buber, in On Judaism, asks, ‘How is life with God still possible in a time in which there is an Auschwitz?’ He acknowledges that one might still ‘believe in’ a God who permitted the Shoah to happen, but he questions the possibility of hearing God’s word, let alone entering into an I-Thou relationship with God: ‘Can one still hear His word? Can one still, as an individual and as a people, enter at all into a dialogical relationship with Him? Dare we recommend to the survivors of Auschwitz, the Job of the gas chambers: “Give thanks unto the Lord, for He is good; for His mercy endureth forever”?’ (p. 224).

And we could go on, citing proposed responses from Epicures, from David Hume, from Gottfried Leibniz, from John Stuart Mill, from Richard Dawkins, from C.S. Lewis, from Thomas Aquinas, from David Bentley Hart, and from others. But the intro to this post has been long enough to introduce the point that one of the surprising features of life for many when they enter the ministry is confrontation with grief and suffering of immense depth. The pastor dare not trot out glib answers which only increase the suffering and betray her or his lack of understanding. But does this mean that pastors can only, and/or must, remain silent? Yes and No.

Enter one qualified to help pastors out at this point – the Lutheran pastor/theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945). And I want to draw here upon John S. Conway’s fine essay, ‘A Meditation upon Bonhoeffer’s Last Writings from Prison’ in Glaube – Freiheit – Diktatur in Europa und den USA: Festschrift für Gerhard Besier zum 60. Geburtstag (ed. Katarzyna Stokłosa and Andrea Strübind; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007), 235–44.

Enter one qualified to help pastors out at this point – the Lutheran pastor/theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945). And I want to draw here upon John S. Conway’s fine essay, ‘A Meditation upon Bonhoeffer’s Last Writings from Prison’ in Glaube – Freiheit – Diktatur in Europa und den USA: Festschrift für Gerhard Besier zum 60. Geburtstag (ed. Katarzyna Stokłosa and Andrea Strübind; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007), 235–44.

One of the most radical challenges to the traditional views of God’s omnipotence and of divine impassibility has come from Bonhoeffer’s pen. On 19 December 1944, from his bleak underground prison in the cellars of the Gestapo headquarters in central Berlin, Bonhoeffer sat down to write a Christmas letter to his fiancée, Maria von Wedemeyer (For more on their correspondence, see Love Letters from Cell 92). In what was to be his final greeting, Bonhoeffer included in that letter a poem to be shared with his parents. The poem, which has been made into a wonderful hymn known as ‘By Gracious Powers’, reads like this:

With every power for good to stay and guide me,

comforted and inspired beyond all fear,

I’ll live these days with you in thought beside me,

And pass, with you, into the coming year.

The old year still torments our hearts, unhastening:

the long days of sorrow still endure;

Father, grant to the souls thou hast been chastening

that thou hast promised, the healing and the cure.

Should it be ours to drain the cup of grieving

even to the dregs of pain, at thy command,

we will not falter, thankfully receiving

all that is given by thy loving hand.

But should it be thy will once more to release us

to life’s enjoyment and its good sunshine,

that which we’ve learned from sorrow shall increase us,

and all our life be dedicate to thine.

To-day, let candles shed their radiant greeting:

lo, on our darkness are they not thy light

leading us, haply, to our longed-for meeting? –

Thou canst illumine even our darkest night.

When now the silence deepens for our hearkening

grant we may hear thy children’s voices raise

from all the unseen world around us darkening

their universal pæan [song of triumph], in thy praise.

While all the powers of Good aid and attend us

boldly we’ll face the future, be it what may.

At even, and at morn, God will befriend us,

and oh, most surely on each new year’s day! (in Letters and Papers from Prison)

These seven short verses bespeak of Bonhoeffer’s trust in God’s enduring and comforting presence during what was the sixth Christmas season of the war and a time of impending and overwhelming disaster. By this time, Bonhoeffer had already been in Tegel prison for nineteen months, mainly in Cell 92. He had been arrested in April 1943 on suspicion of being involved in smuggling Jewish refugees into Switzerland. The investigations had dragged on without resolution for a year and a half. But then in October 1944 he had been transferred to the far more ominous Interrogation Centre of the Gestapo’s main headquarters in downtown Berlin. He now faced the even more severe charges of abetting the conspiracy which had unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler a few months earlier. He would likely be arraigned before the Chief Justice of the People’s Court, Roland Freisler, whose vindictiveness had already sentenced thousands to death for treason against the Reich, and was to do the same to Dietrich’s brother, Klaus. In the meantime the Gestapo was relentlessly trying to entrap him into incriminating confessions about his friends and relatives. What kind of a faith could withstand such ruthless pressures and still witness to God’s powers of goodness?

In this context, Bonhoeffer’s thoughts revolve around the cumulative and appalling suffering of so many people at this crucial stage of the war. From his contacts with the anti-Nazi resistance, he had learnt of the dreadful crimes committed by his countrymen against millions of Jews, Poles, Russians, gypsies and the mentally handicapped. He was equally aware that millions of his own countrymen, including members of his family, had been misled into losing their lives in the service of the Reich’s machinery of violence. How could this suffering be reconciled with a loving Christ? Where is God in all this? Why doesn’t God intervene to put a stop to it? It was just at this critical juncture that Bonhoeffer heard the news that the planned assassination of Hitler had failed. The likely consequences were all too clear, and the tone of his thinking and writing was from then on increasingly filled with foreboding. His preoccupation with suffering and death becomes even more forceful. The imagery and significance of Christ’s crucifixion became ever more real. Out of this came his shortest, but perhaps most memorable, poem, written in the same month, ‘Christians and Others’:

Men go to God when they are sore bestead [placed],

Pray to him for succour, for his peace, for bread,

For mercy for them sick, sinning, or dead;

All men do so, Christian and unbelieving.

Men go to God when he sore bestead,

Find him poor and scorned, without shelter or bread,

Whelmed under weight of the wicked, the weak, the dead;

Christians stand by God in his hour of grieving.

God goes to every man when sore bestead,

Feeds body and spirit with his bread;

For Christians, heathens alike he hangeth dead,

And both alike forgiving. (in Letters and Papers from Prison)

This poem arose out of Bonhoeffer’s bible readings and meditations on the subject of suffering. He was certainly not just preoccupied with his own fate, but rather overwhelmed by the lethal prospects which all his friends in the resistance movement now faced. He knew enough about personal anguish to give authenticity to his statements on suffering. His purpose was to clarify his understanding of a theologia crucis, a theology of the cross.

The poem opens with the universal human desire for relief, for removal of pain, for cessation of suffering, for an end to hunger, for the cleansing of a guilty conscience, for deliverance from death. This makes their religion a form of spiritual pharmacy. But all too often these prayers are not answered. By 1944 the mass murders seemed unstoppable. And Bonhoeffer interpreted the events as Christ being tortured and crucified anew but this time on Nazi Golgothas. Why did God not respond to such heartfelt petitions? Why does it seem that heaven is silent?

Bonhoeffer proposed something of a response to these kinds of questions in his letter dated 16 July 1944:

‘The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God and with God we live without God. God lets himself be pushed out of the world and on to the cross. He is weak and powerless in the world, and this is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us. Matt. 8.17 [‘This was to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet Isaiah, “He took our infirmities and bore our diseases”‘] makes it quite clear that Christ helps us, not by virtue of his omnipotence, but by virtue of his weakness and suffering’. (Letters and Papers from Prison, p. 134)

Bonhoeffer argues that to be a Christian is to stand by Christ in his hour of grieving, on the cross, in jail, in the bombed-out streets and concentration camps. This is a reversal of what ‘religious’ people typically expect.

So Bonhoeffer:

‘Here is the decisive difference between Christianity and all religions. Man’s religiosity makes him look in his distress to the power of God in the world: God the deus ex machina. The Bible directs man to God’s powerlessness and suffering; only the suffering God can help. To that extent we may say that the development towards the world’s coming of age … opens up a way of seeing the God of the Bible, who wins power and space in the world by his weakness’. (ibid)

Abraham Heschel, in his brilliant work The Prophets, helpfully reminds us that for the Hebrew prophets, ‘divine ethos does not operate without pathos … [God’s] ethos and pathos are one. The preoccupation with justice, the passion with which the prophets condemn injustice, is rooted in their sympathy with divine pathos’ (1:218). So we read in Isaiah 63.9–10,

In all their affliction he was afflicted,

and the angel of his presence saved them;

in his love and in his pity he redeemed them;

he lifted them up and carried them all the days of old.

But they rebelled and grieved his holy Spirit;

therefore he turned to be their enemy,

and himself fought against them.

God suffers because God is holy love. If God were incapable of wrath, of being moved to grief by injustice and oppression, God would not be holy; if God were incapable of suffering, of being moved to grief by the pain and agony of the victims of society, God would not be omnipotent love. In his The Crucified God, Moltmann draws out the connection between the wrath and the love of God as grounded in the life of covenant:

God suffers because God is holy love. If God were incapable of wrath, of being moved to grief by injustice and oppression, God would not be holy; if God were incapable of suffering, of being moved to grief by the pain and agony of the victims of society, God would not be omnipotent love. In his The Crucified God, Moltmann draws out the connection between the wrath and the love of God as grounded in the life of covenant:

‘[If] one starts from the pathos of God, one does not think of God in his absoluteness and freedom, but understands his passion and his interest in terms of the history of the covenant. The more the covenant is taken seriously as the revelation of God, the more profoundly one can understand the historicity of God and history in God. If God has opened his heart in the covenant with his people, he is injured by disobedience and suffers in the people. What the Old Testament terms the wrath of God does not belong in the category of the anthropomorphic transference of lower human emotions to God, but in the category of the divine pathos. His wrath is injured love and therefore a mode of his reaction to men. Love is the source and the basis of the possibility of the wrath of God. The opposite of love is not wrath, but indifference. Indifference towards justice and injustice would be a retreat on the part of God from the covenant. But his wrath is an expression of his abiding interest in man. Anger and love do not therefore keep a balance. ‘His wrath lasts for the twinkling of an eye,’ and, as the Jonah story shows, God takes back his anger for the sake of his love in reaction to human repentance. As injured love, the wrath of God is not something that is inflicted, but a divine suffering of evil. It is a sorrow which goes through his opened heart. He suffers in his passion for his people’. (pp. 171–2)

God grieves, then, because of the rebellion of his people; God grieves because of the broken relationship between himself and his creation; God grieves because of the inevitable consequences of human sin and rebellion; God grieves because he remembers what might have been; God grieves because love always hopes! Moltmann talks about the way that God is ‘injured by disobedience and suffers in the people’ who deserve their suffering, but what of the victims of their injustice? What of those who because of the faithlessness of the people of God find it difficult to believe in God?

de Gruchy is helpful here. Again from Theology and Ministry in Context and Crisis:

‘… it is not so much God who is beyond belief, but the church which has lost its credibility. Indeed, if God has become a problem it is precisely because those who claim to believe in God have too often denied him in practice. The credibility of the church’s testimony today is bound up not so much with its intellectual ability to defend the faith, to solve the theodicy problem as traditionally stated, … but far more with the willingness of the church to participate in the suffering of Christ for the sake of the world. And this means to share in the struggle for justice. To be sure, the justification of God can only be resolved eschatologically, but that takes place penultimately in history through authentic witness to the kingdom of God. The God in whom we believe, the God revealed in the crucified Messiah, the God who is present even when he is experienced as absent, and absent when we think he is present, this God has opted to be on the side of those who suffer because of the oppression of others’. (p. 123)

And de Gruchy helpfully reminds us that the suffering of God described so poignantly and powerfully in the Old Testament is not just grief caused by a sinful and disobedient people; it is also suffering with and on behalf of those who suffer as a result of Israel’s sin – the poor, the oppressed, the hungry, the lowly and innocent ones (see p. 113). And he cites from Terence Fretheim’s The Suffering of God: An Old Testament Perspective, p. 108: ‘The human cry becomes God’s cry, God takes up the human cry and makes it God’s own’. This is precisely what Bonhoeffer, in Discipleship, called God’s ‘hour of grieving’, an hour in which and a grieving of such that God invites his people to participate. The church is not simply the community of Christ which suffers vicariously for others. It is also itself the suffering church and itself the victim of oppression.

Certainly Bonhoeffer knew well that the sufferings and deaths he was daily made aware of could not be ascribed to the moral failings of the individuals concerned. Rather these tribulations had, and have, to be understood as the result of collective human willful sinfulness. But God has not withdrawn into a remote impassivity. Rather, God suffers alongside his creation. To repeat:

Men go to God when he sore bestead,

Find him poor and scorned, without shelter or bread …

The depths of divine suffering are reached in the cross where God finds himself ‘whelmed under weight of the wicked, the weak, the dead’.

So what should the responses of Christians, and of pastors, be? Not like others, who merely pass by, to whom the sight of a dead Jew on a cross is nothing. But Christians in this situation of crisis have a particular and significant calling. As Bonhoeffer notes in the last line of verse 2: ‘Christians stand by God in his hour of grieving’. In a letter written to his friend Eberhard Bethge shortly after the poem was completed, Bonhoeffer expanded on this line:

‘This is what distinguishes Christians from pagans. Jesus asked in Gethsemane, ‘Could you not watch with me one hour?’. That is a reversal of what the religious man expects from God. Man is summoned to share in God’s sufferings at the hands of a godless world.

He must therefore really live in the godless world, without attempting to gloss over or explain its ungodliness in some religious way or other. He must live a ‘worldly’ life, and thereby share in God’s sufferings. To be a Christian does not mean to be religious in a particular way, to make something of oneself (a sinner, a penitent, or a saint) on the basis of some method or other, but to be a man – not a type of man, but the man that Christ creates in us. It is not the religious act that makes the Christian, but participation in the sufferings of God in the secular life. That is metanoia: not in the first place thinking about one own needs, problems, sins, and fears, but allowing oneself to be caught up into the way of Jesus Christ, into the messianic event, thus fulfilling Isa. 53 now …

This being caught up into the messianic sufferings of God in Jesus Christ takes a variety of forms in the New Testament. It appears in the call to discipleship, in Jesus’ table-fellowship with sinners, in ‘conversions’ in the narrower sense of the word (e.g. Zacchaeus), in the act of the woman who was a sinner (Luke 7) – an act that she performed without any confession of sin – in the healing of the sick (Matt. 8.17; see above), in Jesus’ acceptance of children. The shepherds, like the wise men from the East, stand at the crib, not as ‘converted sinners’, but simply because they are drawn to the crib by the star just as they are. The centurion of Capernaum (who makes no confession of sin) is held up as a model of faith (cf. Jairus). Jesus ‘loved’ the rich young man. The eunuch (Acts 8) and Cornelius (Acts 10) are not standing at the edge of an abyss. Nathaniel is ‘an Israelite indeed, in whom there is no guile’ (John 1:47). Finally, Joseph of Arimathea and the women at the tomb. The only thing that is common to all these is their sharing in the suffering of God in Christ. That is their ‘faith’. There is nothing of religious method here. The ‘religious act’ is always something partial; ‘faith’ is something whole, involving the whole of one’s life. Jesus calls men, not to a new religion, but to life’. (Letters and Papers from Prison), pp. 135–6)

But where shall we find the strength and the grace to become such disciples? Verse 3 of the poem boldly asserts that, despite the sins we have all committed, despite the barriers we have all erected, despite all our efforts to behave like others, religiously, nevertheless God visits all people in their distress:

God goes to every man when sore bestead,

Feeds body and spirit with his bread;

For Christians, heathens alike he hangeth dead,

And both alike forgiving.

The second line here draws our attention to the eucharist where by sharing with us his body and his blood, Christ draws us into his pain and suffering. To repeat from the poem which we began our discussion on Bonhoeffer with:

Should it be ours to drain the cup of grieving

even to the dregs of pain, at thy command,

we will not falter, thankfully receiving

all that is given by thy loving hand.

Here we are reminded of what Bonhoeffer explores more fully in Discipleship, namely that in his total identification with humanity in incarnation, and then by calling us into fellowship and discipleship with himself, Christ bids us to ‘come and die’.

Here we are reminded of what Bonhoeffer explores more fully in Discipleship, namely that in his total identification with humanity in incarnation, and then by calling us into fellowship and discipleship with himself, Christ bids us to ‘come and die’.

‘The cross means sharing the suffering of Christ to the last and to the fullest. Only a man thus totally committed in discipleship can experience the meaning of the cross. The cross is there, right from the beginning, he has only got to pick it up: there is no need for him to go out and look for a cross for himself, no need for him to deliberately run after suffering. Jesus says that every Christian has his own cross waiting for him, a cross destined and appointed by God. Each must endure his allotted share of suffering and rejection. But each has a different share: some God deems worthy of the highest form of suffering, and gives them the grace of martyrdom, while others he does not allow to be tempted above that they are able to bear. But it is the one and the same cross in every case.

The cross is laid on every Christian. The first Christ-suffering which every man must experience is the call to abandon the attachments of this world. It is that dying of the old man which is the result of his encounter with Christ. As we embark upon discipleship we surrender ourselves to Christ in union with his death – we give over our lives to death. Thus it begins; the cross is not the terrible end to an otherwise godfearing and happy life, but it meets us at the beginning of our communion with Christ. When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die. It may be a death like that of the first disciples who had to leave home and work to follow him, or it may be a death like Luther’s, who had to leave the monastery and go out into the world. But is the same death every time – death in Jesus Christ, the death of the old man at his call. Jesus’ summons to the rich young man was calling him to die, because only the man who is dead to his own will can follow Christ. In fact every command of Jesus is a call to die, with all our affections and lusts. But we do not want to die, and therefore Jesus Christ and his call are necessarily our death as well as our life. The call to discipleship, the baptism in the name of Jesus Christ means both death and life. The call of Christ, his baptism, sets the Christian in the middle of the daily arena against sin and the devil. Every day he encounters new temptations, and every day he must suffer anew for Jesus Christ’s sake. The wounds and scars he receives in the fray are living tokens of this participation in the cross of his Lord. But there is another kind of suffering and shame which the Christian is not spared. While it is true that only the sufferings of Christ are a means of atonement, yet since he has suffered for and borne the sins of the whole world and shares with his disciples the fruits of his passion, the Christian also has to undergo temptation, he too has to bear the sins of others; he too must bear their shame and be driven like a scapegoat from the gate of the city. But he would certainly break down under this burden, but for the support of him who bore the sins of all. The passion of Christ strengthens him to overcome the sins of others by forgiving them. He becomes the bearer of other men’s burdens – ‘Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ’ (Gal. 6.2). As Christ bears our burdens, so we ought to bear the burdens of our fellow-men. The law of Christ, which it is our duty to fulfil, is the bearing of the cross. My brother’s burden which I must bear is not only his outward lot, his natural characteristics and gifts, but quite literally his sin. And the only way to bear that sin is by forgiving it in the power of the cross of Christ in which I now share. Thus the call to follow Christ always means a call to share the work of forgiving men their sins. Forgiveness is the Chrislike suffering which it is the Christian’s duty to bear.

But how is the disciple to know what kind of cross is meant for him? He will soon find out as he begins to follow his Lord and to share his life.

Suffering, then, is the badge of true discipleship. The disciple is not above his master. Following Christ means passio passive, suffering because we have to suffer. That is why Luther reckoned suffering among the marks of the true Church, and one of the memoranda drawn up in preparation for the Augsburg Confession similarly defines the Church as the community of those ‘who are persecuted and martyred for the gospel’s sake’. If we refuse to take up our cross and submit to suffering and rejection at the hands of men, we forfeit our fellowship with Christ and have ceased to follow Him. But if we lose our lives in his service and carry our cross, we shall find our lives again in the fellowship of the cross with Christ. The opposite of discipleship is to be ashamed of Christ and his cross and all the offense which the cross brings in its train.

Discipleship means allegiance to the suffering Christ, and it is therefore not at all surprising that Christians should be called upon to suffer. It is a joy and token of his grace. The acts of the early Christian martyrs are full of evidence which shows how Christ transfigures for his own the hour of their mortal agony by granting them the unspeakable assurance of his presence. In the hour of the cruelest torture they bear for his sake, they are made partakers in the perfect joy and bliss of fellowship with him. To bear the cross proves to be the only way of triumphing over suffering. This is true for all who follow Christ, because it was true for him’. (pp. 43–6)

In October, Bonhoeffer was transferred to the far more ominous and menacing Gestapo prison in central Berlin. But the evidence that we have is that his own faith and trust in his crucified Lord led him to identify more and more with the future hope of resurrection beyond death. So he could therefore face the inevitable testing through suffering by affirming his belief in God’s guiding hand, and the assuredness of God’s nearness. In his final poem ‘By the powers of Good’, the central verse takes up this issue:

Should it be ours to drain the cup of grieving

even to the dregs of pain, at thy command,

we will not falter, thankfully receiving

all that is given by thy loving hand.

When C.S. Lewis lost his wife he wrote at one point in his anguish: ‘Talk to me about the truth of religion and I’ll gladly listen. Talk to me about the duty of religion and I’ll listen submissively. But don’t come talking to me about the consolations of religion or I shall suspect that you don’t understand’ (A Grief Observed, 23). And yet the task of providing consolation has always been a significant part of the work of a pastor. It is, in many ways, a task among the most difficult for the pastor. It is difficult because questions of suffering involve us in the depths of our humanity. And it is difficult because mere human words have no answer to the mystery of suffering.

When C.S. Lewis lost his wife he wrote at one point in his anguish: ‘Talk to me about the truth of religion and I’ll gladly listen. Talk to me about the duty of religion and I’ll listen submissively. But don’t come talking to me about the consolations of religion or I shall suspect that you don’t understand’ (A Grief Observed, 23). And yet the task of providing consolation has always been a significant part of the work of a pastor. It is, in many ways, a task among the most difficult for the pastor. It is difficult because questions of suffering involve us in the depths of our humanity. And it is difficult because mere human words have no answer to the mystery of suffering.

Here we could do much worse that simply listen to the experience of Nick Wolterstorff who, in grief after losing his 25-year-old son Eric in a mountain climbing accident, penned the wonderfully-moving Lament for a Son:

‘What do you say to someone who is suffering? Some people are gifted with wNicords of wisdom. For such, one is profoundly grateful. There were many such for us. But not all are gifted in that way. Some blurted out strange, inept things. That’s OK too. Your words don’t have to be wise. The heart that speaks is heard more than the words spoken. And if you can’t think of anything at all to say, just say, “I can’t think of anything to say. But I want you to know that we are with you in your grief.”

Or even, just embrace. Not even the best of words can take away the pain. What words can do is testify that there is more than pain in our journey on earth to a new day. Of those things that are more, the greatest is love. Express your love. How appallingly grim must be the death of a child in the absence of love.

But please: Don’t say it’s not really so bad. Because it is. Death is awful, demonic. If you think your task as comforter is to tell me that really, all things considered, it’s not so bad, you do not sit with me in my grief but place yourself off in the distance away from me. Over there, you are of no help. What I need to hear from you is that you recognize how painful it is. I need to hear from you that you are with me in my desperation. To comfort me, you have to come close. Come sit beside me on my mourning bench.

I know: People do sometimes think things are more awful than they really are. Such people need to be corrected-gently, eventually. But no one thinks death is more awful than it is. It’s those who think it’s not so bad that need correcting.

Some say nothing because they find the topic too painful for themselves. They fear they will break down. So they put on a brave face and lid their feelings-never reflecting, I suppose, that this adds new pain to the sorrow of their suffering friends. Your tears are salve on our wound, your silence is salt.

And later, when you ask me how I am doing and I respond with a quick, thoughtless “Fine’’ or “OK,” stop me sometime and ask, “No, I mean really.” (pp. 34–5)

It is imperative to the integrity of its witness that the Church takes suffering and grief with the utmost seriousness. And as for death – Death sucks! There is simply nothing positive we can say about it, nor should we seek to live in peace with it. So Wolterstorff again:

‘Someone said to Claire, “I hope you’re learning to live at peace with Eric’s death.” Peace, shalom, salaam. Shalom is the fulness of life in all dimensions. Shalom is dwelling in justice and delight with God, with neighbor, with oneself, in nature. Death is shalom’s mortal enemy. Death is demonic. We cannot live at peace with death.

When the writer of Revelation spoke of the coming of the day of shalom, he did not say that on that day we would live at peace with death. He said that on that day “There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

I shall try to keep the wound from healing, in recognition of our living still in the old order of things. I shall try to keep it from healing, in solidarity with those who sit beside me on humanity’s mourning bench’. (p. 63)

In the face of death, suffering and grief, what the Church is given to know and to hope in and to proclaim is the word of the cross and resurrection. We have no other word! Moltmann’s The Crucified God is characteristically helpful here:

‘The cross of Christ is not and cannot be loved. Yet only the crucified Christ can bring the freedom which changes the world because it is no longer afraid of death. In his time the crucified Christ was regarded as a scandal and foolishness. Today, too, it is considered old-fashioned to put him in the centre of Christian faith and of theology. Yet only when [human beings] are reminded of him, however untimely this may be, can they be set free from the power of the facts of the present time, and from the laws and compulsions of history, and be offered a future which will never grow dark again. Today the church and theology must turn to the crucified Christ in order to show the world the freedom he offers. This is essential if they wish to become what they assert they are: the church of Christ, and Christian theology … Whether or not Christianity, in an alienated, divided and oppressive society, itself becomes alienated, divided and an accomplice of oppression, is ultimately decided only by whether the crucified Christ is a stranger to it or the Lord who determines the form of its existence … In Christianity the cross is the test of everything which deserves to be called Christian’. (pp. 1, 3, 7)

‘We must not only ask whether it is possible and conceivable that one man has been raised from the dead before all others, and not only seek analogies in the historical structure of reality and in the anticipatory structure of reason, but also ask who this man was. If we do, we shall find that he was condemned according to his people’s understanding of the law as a ‘blasphemer ‘ and was crucified by the Romans, according to the divine ordinance of the Pax Romana, as a ‘rebel.’ He met a hellish death with every sign of being abandoned by his God and Father. The new and scandalous element in the Christian message of Easter was not that some man or other was raised before anyone else, but that the one who was raised was this condemned, executed and forsaken man. This was the unexpected element in the kerygma of the resurrection which created the new righteousness of faith’. (p. 175)

‘This deep community of will between Jesus and his God and Father is now expressed precisely at the point of their deepest separation, in the godforsaken and accursed death of Jesus on the cross’. (pp. 243–44)

‘The death of Jesus on the cross is the centre of all Christian theology … The nucleus of everything that Christian theology says about God is to be found in this Christ event. The Christ event on the cross is a God event. And conversely, the God event takes place on the cross of the risen Christ. Here God has not just acted externally, in his unattainable glory and eternity. Here he has acted in himself and has gone on to suffer in himself. Here he himself is love with all his being’. (pp. 204, 205)

So in the face of death, suffering and grief, the Church is called to:

- point to Jesus, the Crucified God, who reveals God’s endangering goodness and suffering love;

- participate in God’s cruciform life by suffering with those who suffer and working to relieve and eliminate suffering. Such cruciformity constitutes the ethical dimension of the theology of the cross found throughout the NT and the Christian tradition. Paradoxically, because the living Christ remains the crucified one, cruciformity is Spirit-enabled conformity to the indwelling crucified and resurrected Christ. It is the ministry of the living Christ, who re-shapes all relationships and responsibilities to express the self-giving, life-giving love of God that was displayed on the cross. Although cruciformity often includes suffering, at its heart cruciformity – like the cross – is about faithfulness and love.

Many of those who have suffered devastating grief or dehumanising pain have, at some point, been confronted by near relatives of Job’s miserable comforters, who come with their clichés and tired, pious mouthings. These relatives engender guilt where they should be administering balm, and utter solemn truths where their lips ought to be conduits of compassion. They talk about being strong and courageous when they should just shut and weep … and pray to the God ‘who comforts the downcast’ (2 Cor 7.6), who is the ‘God of all comfort’ (2 Cor 1.3), who intercedes for us both when we can articulate what we want to say and when all we have are groans, and to whom not even death represents the end.

Many of those who have suffered devastating grief or dehumanising pain have, at some point, been confronted by near relatives of Job’s miserable comforters, who come with their clichés and tired, pious mouthings. These relatives engender guilt where they should be administering balm, and utter solemn truths where their lips ought to be conduits of compassion. They talk about being strong and courageous when they should just shut and weep … and pray to the God ‘who comforts the downcast’ (2 Cor 7.6), who is the ‘God of all comfort’ (2 Cor 1.3), who intercedes for us both when we can articulate what we want to say and when all we have are groans, and to whom not even death represents the end.

But there is a further posture that we are invited, by God, to maintain. And that is the posture of protest prayer. I am reminded here of Karl Barth’s statement, that ‘to clasp hands in prayer is the beginning of an uprising against the disorder of the world’ (cited in John W. de Gruchy, Cry Justice: Prayers, Meditations, & Readings from South Africa, 23). A Christian response to evil is not theodicy, but struggle – the struggle of taking God’s side against the world’s disorder, and of refusing to treat evil as an acceptable part of a larger harmonious vision. Only to the extent that we can confess that nothingness has been vanquished in the self-nihilation of Christ, and met with, struggled with, and overcome may we say that we ‘know’ something of sin and evil’s reality, and be able to speak hopefully of its end.

Finally, for now, the continuity/discontinuity of Jesus’ resurrection provides the ontological basis for Christian hope, promising that of whatever post-resurrection life consists, it is hope in something other than endless continuity. And as meaningful as life’s plots and subplots might be, it is the end (and the more improbable the better) that confers meaning on the whole. It is to bear witness to this end that pastors labour.

◊◊◊

Other posts in this series: