Chris E. W. Green, Toward a Pentecostal Theology of the Lord’s Supper: Foretasting the Kingdom (Cleveland: CPT Press, 2012). ISBN: 9781935931300

Chris E. W. Green, Toward a Pentecostal Theology of the Lord’s Supper: Foretasting the Kingdom (Cleveland: CPT Press, 2012). ISBN: 9781935931300

Reading this study meant jumping some hurdles. First, while it may well say something embarrassing about me and my reading habits, it is not very often at all that I pick up a book of theology and get almost half way through it without recognising more than a handful of the names mentioned therein. Then again, I don’t read a lot of historical theology concerned to tell a particular chapter of Pentecostalism’s story. Consequently, there were times when reading this study by the young Pentecostal theologian Dr Chris Green (the Assistant Professor of Theology at the Pentecostal Theological Seminary in Cleveland) that it felt something like what I imagine it may have been like to visit a foreign country in pre-flying days where even if you recognised something of the language upon arrival there was simply no escaping that you were a long way from home.

And then there was the inkling that a book on Pentecostals and the Lord’s Supper represents something, to say the least, of an oxymoron. But Green has convinced me that while Pentecostals do still have ‘an “allergic response” to the sacramentalism’ (p. 35) of higher church traditions and their ‘sacramental baggage’ (as Amos Young calls it), it was not always so. Indeed, Green goes to considerable length, and depth, to build precisely such an argument, the presentation of which appears to serve his own apologetic purposes and assists him to avoid the cheap and undue polemics so often associated with wider discussions on the Supper.

The book proper begins with a helpful survey of the scholarly literature in which Green documents what Pentecostal scholars have said and are saying about the sacraments in general and the Lord’s Supper in particular. He begins by noting that while it is widely believed – both within and outwith Pentecostalism – that Pentecostals have attended little to sacramental thinking and practice, and that while Pentecostals have often spoken about the sacraments in predominantly negative terms, ‘this is far from the whole of the story’ (p. 5). Surveying the work of a long list of some 40 Pentecostal theologians – from Myer Pearlman, Ernest Swing Williams and C.E. Brown writing in the 1930s and 50s, to figures such as Simon Chan, Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, Jamie Smith and Daniel Tomberlin working more recently and whose work represents something of a ‘“turn” to the sacraments among Pentecostals’ (p. 71) – Green ably catalogues the development and state of Pentecostal theological reflection with regard to the sacraments generally and the Eucharist in particular. He draws attention both to the diverse paths that Pentecostal sacramental theology has taken – it is not an overly unified story – as well as to ‘some common ground’, namely an eschewing of any ‘magical’ views of the sacraments, and a shared allergy of ‘the dangers of liturgical formalism and clericalism’ (p. 72).

Green then turns our attention, in Chapter 3, to a careful and comprehensive reading of the early Pentecostal periodical writings from 1906–1931, attending to the breadth within the movements (e.g., the Wesleyan-Holiness and Finished Work ‘streams’) under the Pentecostal umbrella, and identifying the contours, convictions and habits that characterised early Pentecostal sacramental theology and practice. He concludes by noting that

It is impossible to appreciate early Pentecostal spirituality generally, or their sacramentality specifically, unless one discerns that they arose from a form of imitatio Christi. It was a following of Jesus ‘to fulfill all righteousness’ that fired their experience of the sacraments. They observed the ordinances of water baptism, Holy Communion, and footwashing as occasions for encountering and imitating the risen Jesus and mediation of the grace of divine transformative presence. These rites were never merely ceremonial or memorialistic, although their rich symbolism was not lost on the practitioners. The evidence indicates first generation Wesleyan-Holiness and Finished Work Pentecostals experienced these rites as ‘sacred occasions’, unique opportunities for the Spirit to work in the community. (p. 178)

Green also notes that early Pentecostals ‘did not find themselves compelled to explain the metaphysics of Christ’s presence in the Supper, even though plainly many of them did believe that Christ himself was present to the church through, or at least with, the observance of the Meal. For them, the Lord’s Supper was never merely a memorial feast. Numerous accounts of dreams or visions about the Supper illuminate in an inimitable way how formative the Eucharist was for early Pentecostal spirituality’ (p. 179).

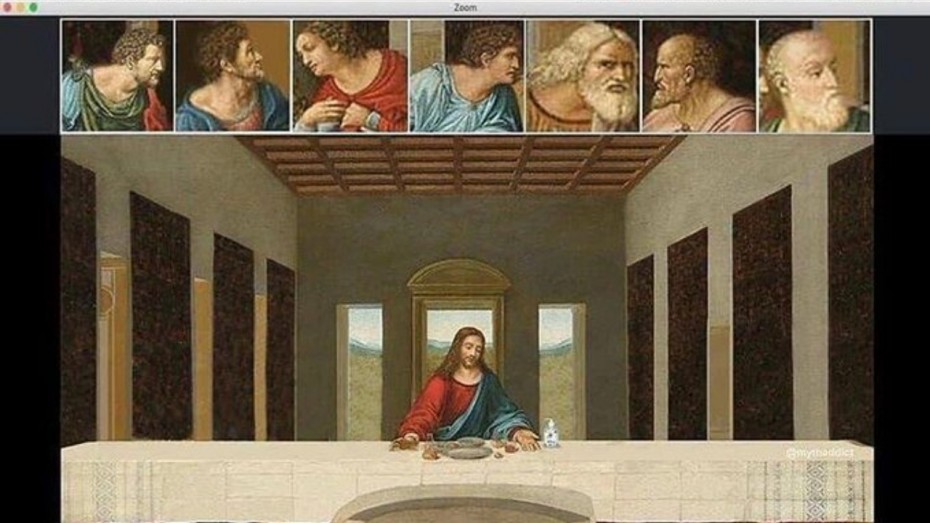

With the literature and historical surveys complete, Green turns then to outline his own constructive proposal beginning, in Chapter 4, with a careful reading and commentary on a number of the key Bible texts, before turning, in Chapter 5, to assemble his own theological vision for a Pentecostal theology of the Supper. Green’s stated intention is to draw ‘heavily on the texts’ “effective history”, allowing what the texts have meant to other Christian readers, pre-modern and contemporary, to influence the shape of [his] own reading’ (p. 3). Matters of hermeneutics and the relationship between Spirit and Word are handled with a watchful and responsible eye, and readings of some key texts (especially Acts 2.41–47, 1 Corinthians 10.14–22 and John 6.25–59, etc.) unearth some creative and theologically mature results. On 1 Corinthians 10, for example, Green consistently and convincingly argues that the Supper ‘shows itself to be one of the ways in which Christ’s body is “there” for the church’ (p. 202), that it is a meal which makes the Community, and which forces on the Community the responsibilities of love such as creativity, humility and longsuffering patience. He suggests too that ‘it is helpful to see the church’s receiving of the Lord’s Supper as a romantic gesture, as a gift between lovers, a tryst with Christ who is jealous for his bride, and a way in which Christ, God fleshed, is bodily present to and for his church’ (p. 207). From the Johannine material, he concludes that because the Gospel teaches us that what happens to us in our sacramental encounter with Christ is beyond human understanding, that it remains too beyond our capacity to answer how it is possible, it also reminds us that the willingness to remain in eucharistic communion with Christ even in the face of confusion marks the decisive difference between those who believe in him and those who do not. Indeed, Green suggests that the mysteriousness of the meal makes possible the articulation of the abiding faith of believers. Furthermore, he proposes that Paul, Luke, and John – in addition to the communities for and to whom they spoke – understood the church’s celebration of the Supper as in some sense a continuation of Jesus’ own ministry, a re-enacting of Jesus’ life of sweeping, boundary-violating hospitality and his atoning death for the life of the world, while all the while pre-enacting the future messianic feast as well. Certainly, Green is, to my mind, correct to consider the Eucharist as both a ‘missionary meal that precisely in its strangeness draws all people to Christ’, and a meal which ‘precisely in its mysteriousness reveals God truly’ (p. 242). He does not neglect ways that the Supper also represents a sounding of divine judgement, even while resituating and re-narrating not only the Church but all creation too into the ‘one story of creation and redemption and consummation, the story of Israel and the church and the world for which they are called as God’s ambassadors and collaborators’. Insofar as the Supper is the promised location in which God in God’s gracious freedom is present in the power of divine love, the Supper is for us ‘the “present tense of Calvary”, and in some sense is also the present tense of all the feasts of God’s people, past and future, including of course the eternal messianic banquet’ (p. 241).

Chapter 5 represents the book’s theologically most constructive chapter, and is concerned with discerning and proposing a theologically mature Pentecostal theology of the Supper. Here is Green in full flight, attending in some detail to those issues that he adjudges to be especially important to Pentecostals. These Green identifies early in the book as ‘questions of how God works in and through the church’s celebration of the Communion rite and how Christ and the Spirit are personally present and active in the eating and drinking of the Eucharistic bread and the wine’ (pp. 3–4). Here he is also concerned with issues of praxis, and with forms of Eucharistic practice which are both recognisably catholic and distinctively Pentecostal. Against the perception – or reality – that many if not most distinctly Pentecostal theologies of the sacraments have tended to be carried out in exclusively baptistic terms, complete with an imbalance on the Supper’s memorialist dimensions and even being spoken of as ‘mere ordinances’, Green reminds his readers that this has not always been the case, and he proceeds in this chapter to bring ‘the fathers and mothers of the Pentecostal movement’, the exegetical work undertaken in the previous chapter, and dialogue partners from both within and outwith the Pentecostal tradition(s) to put forward a ‘constructive and revisionary proposal’ for a theology of the Supper, concerned to ‘remain true to the biblical witness and [to] the Pentecostal tradition’ (pp. 244–45). Along the way, Green attends to many of the familiar themes associated with theologies of the Supper – e.g., the Supper as Divine Lex, the Supper as thanksgiving, Supper as anamnesis, Supper as covenant renewal, Supper as a location for Spirit-led discernment, Supper and healing, Supper as divine-human dialogue, Supper and soteriology, Supper and sanctification or ‘moral formation’ (p. 312), Supper and theological method, Supper and mission, Supper and worship, Supper as a sign and foretaste of eschatological feast or what Green calls ‘an ontologically-transforming proleptic share in the metaphysics of the life everlasting’ (p. 271), etc. – and he does so in ways that betray a mind that is well read and conversant with the issues, with courage to identify practices and ideas that are problematic, and with a genuine concern for the church and her faithful witness to the Word of which she is a creature. The section on the metaphysics of the Supper, in particular, echoes rich Jensonesque tones, skilfully accompanied by John of Damascus and Sergius Bulgakov. It is Green’s contention that ‘Christ is really, personally, and bodily present in Communion because the Father wills it and the Spirit makes it so for the sanctification of the church on mission in the world. In the Eucharist-event’, he believes, ‘the Spirit “broods over” the cosmically-enthroned Christ, the celebrating congregation, and the elements on the Table, opening the celebrants to the presence of the risen Jesus who the Spirit makes in that moment bodily present for them with, in, and through the thereby-transfigured bread and wine’ (p. 282). Green also believes that short of the beatific vision, Christ’s ‘embodiment at the Father’s right hand includes the Eucharistic bread and wine, the preached Gospel, and the sanctorum communio’, and [that] these last serve as sacraments – effective signs in the present of the future eschatological state of things’ (p. 283). So, contra Herbert McCabe, Green contends that bread and wine are ‘both-at-once’ natural objects and eschatological objects. Put otherwise, bread and wine ‘remain natural objects that have been eschatologized’ (p. 285).

On the question of hermeneutics, Green argues that ‘the charismatic and Eucharistic community as it communes in the Spirit with the totus Christus is the authoritative interpreter of Scripture. As a result, it is in the context of the community’s Spirit-baptized and Spirit-led Eucharistic worship that believers learn best what Scripture is and is for, and over time learns the habits necessary for reading faithfully, with an ever-deepening appreciation for Scripture’s “fuller sense”. All the many other faithful uses of Scripture, whether scholarly or devotional, pastoral or evangelistic, should be judged in this light’ (p. 296). And on the question of how the Supper relates to Christian worship, Green is concerned throughout, and appropriately so, to ‘guard against the flattening and hardening of the sacramental celebration into mere ritual’ (p. 319). He is equally concerned that ‘the Eucharist-event should be recognized as the hub of the worship service … as the hearth around which all the other liturgical furniture is arranged’ (p. 316). Fair enough, but just how the Supper is to be both ‘framed and undergirded by Pentecostal practices, such as the altar call, “tarrying”, prayers for healing, testimonies, and footwashing’ (p. 317) is not spelled out, readers being left to work out on their own how such practices ‘underscore the communal reality of Communion’ (p. 318).

The study concludes with a description of major contributions and an invitation to further research.

My enthusiasm for this book does not mean that there are not things therein that disappoint or distract. Here I will note just three: The first concerns the scattering throughout of Latin and Greek phrases. Where such are necessary – and this, I suggest, is on a much rarer occurrence than we find here – some translation should have been provided, particularly for the benefit of those readers unfamiliar with the terms. As it stands, it may just be for many readers a distraction from and hurdle within the main flow of the writing.

Second, there is, from time to time, a creeping Pelagianism at work in this essay. Perhaps just one example will suffice. At the conclusion of Green’s stimulating and fruitful exegesis on some of the key New Testament texts, he suggests that ‘these texts teach us that the sharing of a common loaf and cup is truly the Lord’s Supper for us only as we faithfully respond to the Word of God that comes to us alongside, through, and as the sacred meal’ (p. 242. Italics mine). Not only does such a claim seem to be somewhat at odds with what Green has stated elsewhere in the book (for example, on p. 285: ‘the reality of Christ’s and the Spirit’s shared presence in the Supper does not wait on our believing (in) it. Christ is there by the Spirit, whether we believe it or not’. Italics mine.), but short of interpreting such statements in a more explicitly trinitarian framework, and that particularly in ways that highlight the vicarious humanity of the Son and the revelatory work of the Spirit, such claims on their own threaten to undermine or deny the depths of the twofold movement that God makes possible when and as the baptised gather around broken loaves and generous helpings of pinot noir.

Third, while Green’s essay has been strengthened significantly via (mostly) judicious engagement with voices from across the ecumenical amphitheatre, it is disappointing and unfortunate that there is relatively little engagement therein with the best of the Reformed tradition (to be sure, he draws briefly upon the work of Michael Welker, Jürgen Moltmann and J. Rodman Williams), and that for a number of reasons. Not only is the Reformed a project with considerable sympathy at countless points with that brand of Pentecostalism Green is keen to encourage, but also because such a conversation may well have served to bring some needed clarity around the issue I raised above regarding whatever creeping Pelagianism may exist. I wonder too whether if Green had drawn more on the Reformed (and especially upon John Calvin and, perhaps, George Hunsinger) and less on the Anglicans, the Orthodox and Robert Jenson (upon whom he relies heavily in the final chapter), the thesis would have been considerably better served and the book’s reception among Pentecostals better attend to Green’s own apologetic intention.

These three caveats aside, there is no doubt in my mind that Pentecostals – and not only Pentecostals – will be much blessed, challenged and inspired in the reading of this fine study, a study that is indeed intended ‘first and foremost as a conversation starter for the Pentecostal communities’ (p. xi). To be sure, some readers both from within and outwith that ecclesial tribe may lament that the volume lacks hard critique of current Pentecostal practice, and that Green’s presentation is so revisionist that one can only really read here a ‘Pentecostal’ theology of the Supper by underscoring the word ‘Toward’ in the title, but that would be most unfair, for Dr Green has served up a great dinner here, and I suspect that his readers will no doubt find themselves as I do – in his debt. Now let the conversation begin!