Luke Hankins (ed.). Poems of Devotion: An Anthology of Recent Poets (Eugene, OR.: Wipf and Stock, 2012). 236pp; ISBN: 978-1-61097-712-8

Luke Hankins (ed.). Poems of Devotion: An Anthology of Recent Poets (Eugene, OR.: Wipf and Stock, 2012). 236pp; ISBN: 978-1-61097-712-8

A guest-review by Mike Crowl.

Luke Hankins is not quite thirty. He’s already published a highly regarded book of poems, Weak Devotions, in which he ‘wrestles with the issues Donne, Herbert, Hopkins … also found worthy of their most impassioned work’ (John Wood), and a chapbook of translations from the French poems of Stella Vinitchi Radulescu (three of her poems are included in this book). He is also senior editor of the Asheville Poetry Review.

In Poems of Devotion, Hankins is aiming to present to the modern reader a substantial collection of poems on the theme of devotion, from a wide range of poets – American, English, and other nationalities, including some translations. If the word ‘devotion’ arouses thoughts of prissy, sappy pseudo poems that barely scratch the surface, you will find Hankins’ collection eschews such works; much of what is here is tough, painful, meditative, worshipful, and certainly deep enough to call you back again and again.

Hankins presents poets who are willing to wrestle with God. Many of them come from angles that are anything but devotional in the generally accepted sense. Some know from the outset where they’re going, but Hankins has looked more for poets who appear to work out their experience as they go along. As he writes in his introduction: ‘Great poems are – if not invariably, at least most often – an unfolding, not only for the reader, but for the poet in the process of composing’. And he quotes fellow poet, Charles Wright: ‘Writing is listening. Religious experience is silent listening and waiting. I have always been able to tell whether something I am writing is genuinely an expression of revelation or if it’s just me exercising my intellect. I can feel the difference, see it and taste it, but I don’t know how I can do that’. In the poems collected here, poetry is for the most part a means of meditating rather than an experience recounted.

That is not to say that these are floppy works without poetic structures: subtle rhymes and rhythms abound, the last lines are often a revelation; sharp metaphors of atmosphere and the spirit and creation are evident on every hand. The poets have taken their original searchings and crafted them well.

Many of these poets are not ‘saints’ in any ordinary sense, though they bring themselves to understand the need to submit to God’s will, even when it seems at odds with their very being, or when they haven’t found the answer they set out to look for. Old poets still look for answers in their old age. (Leonard Cohen has a couple of very good prose poems, for instance). There is also great joy and wonder (for example, in Luci Shaw’s Mary’s Delight; Shaw isn’t a poet I’ve greatly admired in the past, but this is a beauty) and praise (several poems are modern psalms) and worship (Thomas Merton’s Evening: Zero Weather, for instance).

Then there are the strange poems: Amit Majmudar’s extraordinary long piece about the angel we generally know as Satan; Michael Schiavo’s odd ‘dub versions of Shakespeare’s sonnets’, Bruce Beasley’s long, collage-like ‘Damaged Self-Portrait’.

Hankins offers seventy-seven poets in all. Some have only one poem, some have several, some provide several parts of a larger poem. But there’s no sense of stinting on the poets here; each one has room to breathe. There are some familiar names – T.S. Eliot, Theodore Roetke, E.E. Cummings, R.S. Thomas, Denise Levertov, Richard Wilbur – but the majority are unfamiliar – to me, anyway, and I suspect to many readers of the book.

The poems are book-ended by the substantial introduction, and a reprint of an interview between Hankins and Justin Bigos, which gives some background to Hankins and his poetic stance.

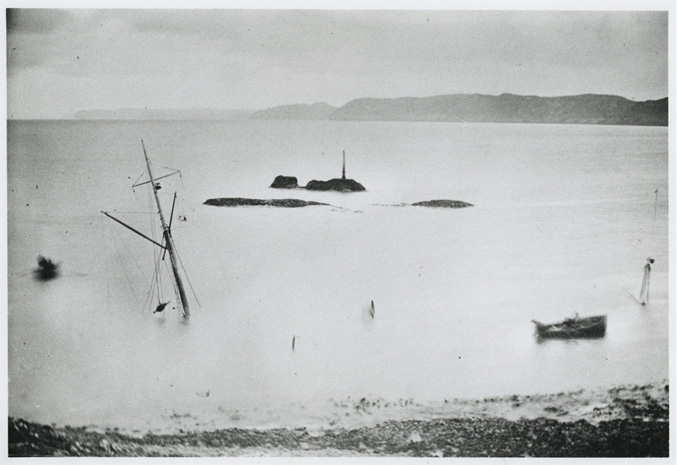

He mentioned too about a recent meeting of Japanese and Korean theologians who conversed about the situation birthed by the Fukushima tragedy. Among the topics discussed was the possibility of post-mortem salvation for the many victims of the tsunami and of radiation poisoning. He said,

He mentioned too about a recent meeting of Japanese and Korean theologians who conversed about the situation birthed by the Fukushima tragedy. Among the topics discussed was the possibility of post-mortem salvation for the many victims of the tsunami and of radiation poisoning. He said,