On 30 November 2016, the Senate of the Australian Federal Parliament resolved to establish a Select Committee to inquire into the Commonwealth Government’s exposure draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill. The Committee is due to report on or by 13 February this year.

On 30 November 2016, the Senate of the Australian Federal Parliament resolved to establish a Select Committee to inquire into the Commonwealth Government’s exposure draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill. The Committee is due to report on or by 13 February this year.

The Committee is looking into religious views on amending the Marriage Act, and is using Attorney-General George Brandis’ Exposure Draft Bill on Marriage as a reference point. To be clear, the committee is not asking whether the law should change. Rather, it is asking what, assuming a change of law, might be the implications of such a change, including implications for religious bodies and organisations.

The background to this inquiry is in part the suggestion from many religious leaders and religious lobby groups that legalising same-sex marriage threatens to undermine religious freedoms and communities. This concern, almost always poorly expressed, is possibly the highest hurdle still to be passed if there is to be a change in law. Yet it is not at all an argument against same-sex marriage itself. At most, it is merely a claim that amendments to the law should safeguard religious interests, some cultural geography, and the rights of religious communities to mark marriage in ways consistent with their particular ‘doctrines, tenets or beliefs’.

Submissions from a variety of religious perspectives are welcome and vital at this stage. The Committee is receiving submissions by email and online only until next Friday 13 January.

The Committee invites short submissions, written in one’s own words (pro forma submissions, in other words, will be disregarded), from all sections of faith groups. It will also accept submissions from those who wish their names not to be publicly disclosed. This is an important safeguard so that all views can be freely expressed.

The Committee has provided some general advice here on preparing submissions. In addition, a friend of mine has provided a helpful framework for making a submission on this particular inquiry:

Guidelines for Submission

Address to: Committee Secretary, Select Committee on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill, Department of the Senate, PO Box 6100, Canberra ACT 2600.

Heading: Submission to Select Committee on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill

Your Name, Title & Contact Details

(+ if you wish: ‘I do not wish my name to be disclosed publicly’.)

Reason for Writing – who you represent

Give the Committee an insight into who you represent. For ordained members of religious bodies, this is mostly self-evident. For others, however, it is suggested that you sketch some background of your involvement in your religious organisation. In particular, mention any leadership roles that you have fulfilled, such as committees, volunteer roles, etc., as well as the length and extent of your involvement. Your age too may be added – young people’s views are typically under-represented. Clergy should include positions held and all titles.

Reason for Writing – your interest in this issue

A personal connection to the issue is relevant. For example, your engagement with or in the LGBTIQ community, your conversations with friends, relatives, and religious communities, and your involvement in public discourses around this matter can be mentioned here. Mention also any previous submissions that you have been involved in, if and where you have written on the topic, and ways that you have been involved in advocacy in any form.

Your Views on the Terms of Reference (*)

Many legal experts will be giving advice on the technicalities of the legislation – you don’t need to do that. More important here is to convey views of people of faith ‘on the ground’. For example:

‘I remember when the Church changed its position on divorce by accepting divorcees for re-marriage. The law didn’t need to be changed during that major change. Some ministers refuse to remarry divorcees and I don’t see the need for any extra powers to refuse same sex couples’. [add a personal anecdote to illustrate]

Or,

‘I have same-sex friends who wish to marry. They would never contemplate “forcing” an unwilling minister to marry them against his/her wishes. What kind of wedding would that be?’

(*) It’s often helpful to highlight the Terms of Reference (ToR) addressed. You can put the ToR as a sub-heading or simply put ‘Term of Reference (a)’ – they’re numbered (a)–(d).

The Committee’s advice here is clear:

Please read the terms of reference carefully before making your submission. The committee has resolved that it will only accept submissions strictly addressing its terms of reference, with a particular focus on the following areas:

- the proposed exemptions in the Exposure Draft for ministers of religion, marriage celebrants and religious bodies and organisations to refuse to conduct or solemnise marriages, and the extent to which those exemptions prevent encroachment upon religious freedoms;

- the nature and effect of the proposed amendment to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984;

- whether there should be any consequential amendments to this bill, or any other Act, and, if so, the nature and effect of those consequential amendments.

Substantive submissions that explore the technical aspects of the terms of reference will be published, however the committee does not have the resources or time to consider short statements expressing support either for or against same-sex marriage. As such, these statements will be treated as correspondence and not published.

As mentioned, claims about the denial of religious freedom are central. Fears being raised include ministers being forced to officiate at same-sex weddings, churches being forced to hold same-sex weddings in their buildings, and religious bodies being forced to provide commercial goods and services to same-sex weddings. The draft Bill aims to address these fears by adding multiple means for faith groups to refuse involvement in same-sex weddings. But many think these new measures go too far. The Bill singles out same-sex couples as the paramount concern of religious people. It also provides brand new, potentially sweeping, powers for refusal by religious groups – and even civil celebrants.

Analysis of the draft Bill by Australians for Equality is here and here. For a different perspective, see the Australian Christian Lobby’s analysis here.

Personal stories have great value. Just keep them clear, concise, and relevant to the Terms of Reference (remembering that this inquiry is not about if the law should change but about what effects would result from the change). Don’t worry about making lots of points. One well-made point serves best.

Closing

Conclude with a statement on the effect of legalising same-sex marriage on your faith community, and a recommendation. A conclusion + recommendation might be:

‘The existing Marriage Act already gives my religious body/ministers sufficient power to refuse to officiate at, or participate in, same sex weddings.

Recommendation: A law that recognises marriage irrespective of gender should retain and not exceed these powers’.

≈

Remember, the closing date is Friday 13 January. You can make a submission by either emailing it or uploading it online.

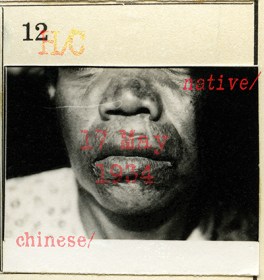

Among the many Constantinian assumptions that much Protestantism shares quite uncritically with Rome is a commitment to modes of imperialism that preference and propagate particular cultural forms. The near-idolatry of, and proclivity to proliferate, its own forms, coupled with an ecclesiocentric view of the world, has very often restricted the church from entering into unfamiliar territory in anything but highly-qualified and guarded ways – ways usually accompanied by the violent protection of the state, such as was the case with the Conquistadors (lit. ‘conquerors’) who sought to extend the bounds of Europe to the Americas, to Oceania, to Africa, and to Asia.

Among the many Constantinian assumptions that much Protestantism shares quite uncritically with Rome is a commitment to modes of imperialism that preference and propagate particular cultural forms. The near-idolatry of, and proclivity to proliferate, its own forms, coupled with an ecclesiocentric view of the world, has very often restricted the church from entering into unfamiliar territory in anything but highly-qualified and guarded ways – ways usually accompanied by the violent protection of the state, such as was the case with the Conquistadors (lit. ‘conquerors’) who sought to extend the bounds of Europe to the Americas, to Oceania, to Africa, and to Asia.

It really is an incredible time to be thinking about and learning from Dietrich Bonhoeffer, that pastor and teacher who from a life cut short over 70 years ago left us a profound vision of what it might mean to speak responsibly of ‘God’ and of ‘the world’ in the same breath, and to be Christian community in one of the most violent and unstable and disenchanted times in recent human history. Rather than seek to escape such realities, Bonhoeffer believed that to follow Jesus is to be thrown ever more deeply into them, into the darkness. He taught us that the first place to look for Christ is in hell, and that it is ‘only by living completely in this world that one learns to have faith’. It is only by ‘living unreservedly in life’s duties, problems, successes and failures, experiences and perplexities’ that, he said, we ‘throw ourselves completely into the arms of God’. And this means, for Bonhoeffer, that ministers of the gospel are ‘not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice’ but rather are called to ‘drive a spoke into the wheel itself’.

It really is an incredible time to be thinking about and learning from Dietrich Bonhoeffer, that pastor and teacher who from a life cut short over 70 years ago left us a profound vision of what it might mean to speak responsibly of ‘God’ and of ‘the world’ in the same breath, and to be Christian community in one of the most violent and unstable and disenchanted times in recent human history. Rather than seek to escape such realities, Bonhoeffer believed that to follow Jesus is to be thrown ever more deeply into them, into the darkness. He taught us that the first place to look for Christ is in hell, and that it is ‘only by living completely in this world that one learns to have faith’. It is only by ‘living unreservedly in life’s duties, problems, successes and failures, experiences and perplexities’ that, he said, we ‘throw ourselves completely into the arms of God’. And this means, for Bonhoeffer, that ministers of the gospel are ‘not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice’ but rather are called to ‘drive a spoke into the wheel itself’.

The one thing that is certain in our current political climate is that things are ‘deeply uncertain and fluid’ (Rowan Williams). The other one thing that is certain is that those in liberal democracies are embroiled in a real battle about power, and about what role, if any, the ‘existing rulebook’ (Bretherton) will play, and about the possibility of living a genuinely-shared life (with or without the hassle of all those left-leaning loopheads

The one thing that is certain in our current political climate is that things are ‘deeply uncertain and fluid’ (Rowan Williams). The other one thing that is certain is that those in liberal democracies are embroiled in a real battle about power, and about what role, if any, the ‘existing rulebook’ (Bretherton) will play, and about the possibility of living a genuinely-shared life (with or without the hassle of all those left-leaning loopheads  After César Vallejo

After César Vallejo Call me ‘old school’, but I’m really not very tolerant when it comes to damaging public property. Places such as parks, public libraries, schools, rivers, parliaments, etc. are, in my view, sacrosanct, and when such places undergo vandalism the damage is done to us all. More specifically, when such damage is undertaken for the economic gain of a few, there really can be no acceptable defence at all.

Call me ‘old school’, but I’m really not very tolerant when it comes to damaging public property. Places such as parks, public libraries, schools, rivers, parliaments, etc. are, in my view, sacrosanct, and when such places undergo vandalism the damage is done to us all. More specifically, when such damage is undertaken for the economic gain of a few, there really can be no acceptable defence at all.

On 30 November 2016, the Senate of the Australian Federal Parliament resolved to establish a

On 30 November 2016, the Senate of the Australian Federal Parliament resolved to establish a