It was the best of times,

it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief,

it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light,

it was the season of Darkness,

it was the spring of hope,

it was the winter of despair,

we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way— in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only. (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities)

It was indeed something of a Dickens of a General Assembly, about which I’d thought I’d share a few reflections.

There were a number of genuine springs of hope for which I give thanks:

- The powhiri and service of worship at the Church’s national marae at Ohope, hosted by Te Aka Puaho, was very special, overcoming all the challenges of weather, logistics and a crummy sound system. One of the real highlights for me was when Richard Dawson presented the new moderator, Ray Coster, with a copy of the church’s confession of faith, Kupu Whakapono, written in Te Reo Maori, followed by a sung version led by Malcolm Gordon. The Assembly was last held at the marae in 1984 – too long ago – and this Assembly marked, in a number of significant ways, including Wayne Te Kaawa’s rousing speech during the Assembly business time, a maturation in the church’s bicultural journey.

- The former moderator, Peter Cheyne, spoke well about the things that have inspired him throughout his moderatorial term: ministry and mission at the grassroots, the caring witness of the people of God in Christchurch, his ongoing concern for a church committed to discipleship and to raising biblical literacy.

- The decision to call upon a foreign government (i.e., the New Zealand Government) – and hopefully there are responsibilities here that the church might be able to undertake as well – to establish relocation strategies with the governments of Pacific island nations in danger of disappearing as a result of climate change.

- It is always a highlight for me when we welcome international guests and observers. This GA, we welcomed 16 guests from Korea, Burma, Chile, Vanuatu and Tahiti.

- The church backed the campaign by Living Wage Aotearoa New Zealand. Margaret Mayman made the point that ‘people and their work have a dignity that makes the labour market substantially different from the purchase of other goods. The price of a person’s labour shouldn’t be determined solely by the market’. This is good news for theologians!

- I always have a real sense of pride when ex-students rise to speak. They invariably do so with a neat combination of wisdom and wit, and I reckon that their fresh – and most often younger – voices offer one of the most important contributions to the discussions.

- The moderator modelled grace, good humour and appropriate dignity throughout. Well done Ray!

- I have mixed feelings about the GA’s decision to grant presbytery status to the Pacific Islands Synod. (Howard Carter expressed my mind well.) Given the decision, however, we might have marked this significant event with more carnivalesque fanfare than we did.

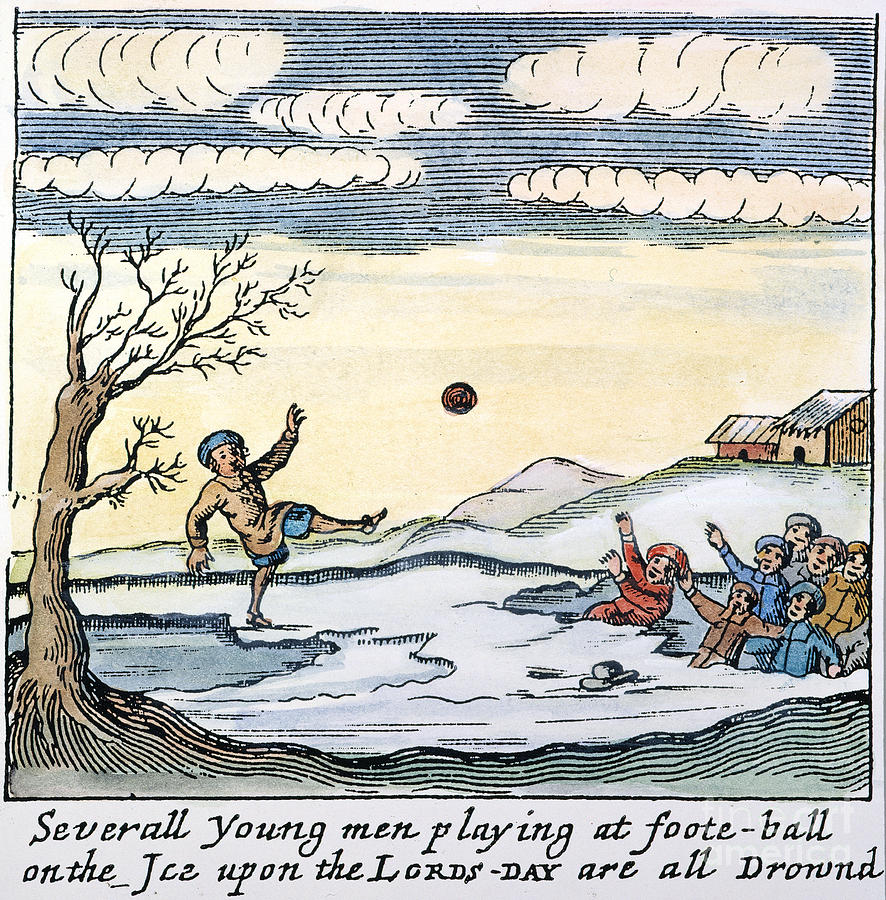

And there were a number of factors which signified that we had indeed entered an ‘epoch of incredulity’ – all-too-familiar territory for the church. Among these were:

- No real coffee. I fail to see how anyone can be expected to discern the will of God without real coffee. This is the one great tragedy of the GA!

- While I’m on the matter, the vote to support the living wage movement seemed to be radically undermined by the absence of any Fair Trade beverages.

- And while I’m on the matter of hypocrisy, the church’s rhetoric of concern regarding climate change seems at odds with our decision to have hundreds of people jump into aeroplanes to attend one of these gatherings and then think little of the environmental cost of such a decision. My minister – peace be upon him – raised a wonderful point about this incongruence. He could have also mentioned something about the number of forests we raped doing our holy business.

- Apart from the few extra-ecclesial matters that were discussed, the highest court of the denomination – charged as it is with the solemn and joyous responsibility of listening for and to the divine voice in the world – seems to be much more interested in clanging its own cymbals and blowing its own bassoons. This is not altogether unexpected for it is almost inevitable that anxiety would drive us toward Pelagianism.

- The processes of discernment employed by the GA seem to be particularly successful in turning otherwise fine and friendly souls into packs of frightened, blind and deaf wolves. Put otherwise, the church seems to lack the imagination – and/or the theological resources and/or the leadership – required to enter into processes of discernment in ways other than marked by an unholy cannibalism with make a stranger stare (and then walk away) and which perpetuate cycles of abuse from one generation to the next. Like modern day Israel, those who were once victims now employ the very same tactics that they learnt from their abusers, tactics which disempower others to equally ugly effects and cycles which can only be broken by the ministry of mediation and healing given to us in God. Such behaviour served to remind me that the gospel is not a set of doctrines or ideologies, no matter how carefully articulated and well-intentioned – and that with due fidelity to Scripture – but a person; namely, Jesus the Christ. When our ethics, processes, practices, decisions and speech are cut loose from him they roam in the desert of meaning out of step with the grain of the universe, a desert that breeds a kind of unholy desperation out of step with apostolic faith. I know that the Church is the glorious bride of Christ, and the most beautiful creature in creation, but she really can be an ugly and vexatious bitch sometimes.

- Much of the debate concerned vexed matters around sexuality and leadership. It is really disappointing – not least because it is most unprotestant! – that both sides insist on grounding their arguments in logic devoid of any kind of christology. Either way you walk, Jesus simply seems to make no difference. For those on the left, the argument seems to be grounded in notions of ‘natural justice’, while those on the right insist on the making their case on the basis of ‘nature’. (I am, of course, aware of St Paul’s words about ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’ intercourse in Romans 1, but remain entirely unconvinced that Pauline anthropology would sponsor the argument as articulated by traditionalists.) I wonder what might happen were both ‘sides’ to sit at the Lord’s Table together – the most suitable place for debate, and for love making – and begin with a different question; namely, who is Jesus Christ? That said, I am deeply encouraged that some of the ministry interns are trying to do precisely that! I am also deeply encouraged by a number of signs that the hard lines that have characterised our church in the past show real signs of wear and tear. Perhaps a new vision of being church together may result, a vision unenslaved to those modes of modernity which insist on perpetuating irrelevant and outmoded structures of top-heavy leadership – we really don’t need a presbyterian pope! – and where the rhetoric of ‘servanthood’ and ’empowerment’ and ‘local’ continue to characterise where the real action takes place.

- Among the many motions upon which the recent GA was invited to discern the mind of God God (quite a bold if not ridiculous thought when you think about it that way) was whether or not an invitation ought to be made to our Church’s Doctrine Core Group to ‘prepare a discussion paper on the theology of marriage within the Presbyterian Church, and explore its implications for public covenants of same-gender relationships’ (Notice of Motion #133). Given the liveliness of this topic in wider NZ society, and a long-standing Presbyterian tradition of seeking the welfare of the city, one may not be surprised to learn that not a few who attended Assembly were profoundly disappointed and somewhat bewildered when this motion received the support of less than half of the voting commissioners. I was also surprised to learn that this significant matter was not even reported on the PCANZ website among the list of items discussed on Saturday. (NB. I am not suggesting that anything sinister or underhanded is going on here, but simply making the observation). There are many things one might deduce from such a decision of our church’s highest court, but I am not interested here in commenting on these. Rather, I wish to offer a few observations about how and why such a move is so foreign to the best instincts of our tradition.

The Reformed faith is, according to John Leith, ‘not a fixed pattern of church life but a developing pattern that has both continuity and diversity’. Being reformed, in other words, is not so much about espousing certain doctrines or sharing a particular interpretation of the Bible but is rather about the fact that one has committed oneself to being involved in a certain kind of project: the project of renewing the faith according to the Word of God. So Michael Jinkins:

The Reformed faith is more an ongoing project than it is a tradition, a denomination, or even a communion, though it has elements of each of these. When we say, ‘We are Reformed,’ we are saying that we are Christians committed to a particular project. The Reformed project is concerned not so much with defining and defending such things as the uniqueness of a Reformed tradition as it is with recovering, in each new generation, Christian faith as God’s calling of humanity to new life in Jesus Christ. Such a mission reflects the commitment of John Calvin ‘to renew the ancient form of the church.’ Whenever the Reformed movement has become preoccupied with itself it has missed the point of its existence. The Reformed project exists to draw our attention to Jesus of Nazareth in whom God is revealed and through whom God redeems creation … This does not mean that there are no distinctive features of what we might call ‘Reformed faith.’ There are particular emphases that have distinguished the Reformed approach to Christian faith from that of other Christians. But these Reformed emphases remain just that: emphases. The most distinctive aspect of the Reformed faith is also its most catholic, or universal: its unflagging commitment to articulate the gospel of Jesus Christ.

The reformed project, in other words, is not about our beliefs, or our righteousness, or our values, or our interests, or our devotion, or our aspirations, or our hopes. The reformed project is about what the Christian faith is about – namely, the God revealed in Jesus Christ. It is about who this God is and what this God is doing in the world. It is about ever calling the church catholic to fulfil our vocation as witness-bearers to this good news. So the reformed minister and theologian Karl Barth understood that in theological study we are ‘always to begin anew at the beginning’. And, for Barth, as for all those engaged in the reformed project, the beginning point is never a concept or a principle. The beginning point is always a name: Jesus Christ. One simply cannot arrive at the right answers until one sets off with the right question. And the ‘quintessential question’ (Bonheoffer) facing our church is not, ‘What can the Reformed tradition do to ensure that it has a future?’ Or, even worse, ‘How can we guarantee the survival of the Presbyterian Church?’ Rather, the right questions are ‘Who is Jesus Christ?’, and ‘What is he up to?’, and ‘What is he calling us to participate in?’ The Lutheran theologian Ernst Käsemann expressed this well when he wrote: ‘Wherever ecclesiology moves into the foreground, however justifiable the reasons may be, Christology will lose its decisive importance, even if it does so by becoming integrated, in some form or other, in the doctrine of the church, instead of remaining the church’s indispensable touchstone’. And Barth too is worth citing here at length:

Theological work is distinguished from other kinds of work by the fact that anyone who desires to do this work cannot proceed by building with complete confidence on the foundation of questions that are already settled, results that are already achieved, or conclusions that are already arrived at. He cannot continue to build today in any way on foundations that were laid yesterday by himself, and he cannot live today in any way on the interest from a capital amassed yesterday. His only possible procedure every day, in fact every hour, is to begin anew at the beginning. And in this respect theological work can be exemplary for all intellectual work. Yesterday’s memories can be comforting and encouraging for such work only if they are identical with the recollection that this work, even yesterday, had to begin at the beginning and, it is to be hoped, actually began there. In theological science, continuation always means ‘beginning once again at the beginning.’ In view of the radical exposure of this science to danger, this is obviously the only possible way. The endangering of theology is strong enough to cut the ground away from under the feet of the theologian time and again and to compel him to look around anew for ground on which he can stand as if he had never stood on such ground before. And above all, the ever-new start is the only possible way because the object of theology is the living God himself in his free grace, Israel’s protector who neither slumbers nor sleeps. It makes no difference whether theological work is done with attention to the witness of Scriptures, with the reassuring connection to the communio sanctorum of all times, and certainly also with a thankful memory of the knowledge previously attained by theology. If God’s goodness is new every morning, it is also every morning a fully undeserved goodness which must give rise to new gratitude and renewed desire for it.

For this reason every act of theological work must have the character of an offering in which everything is placed before the living God. This work will be such an offering in all its dimensions, even if it involves the tiniest problem of exegesis or dogmatics, or the clarification of the most modest fragment of the history of the Church of Jesus Christ, but, above all, if it is the preparation of a sermon, lesson, or Bible study. In this act of offering, every goal that previously was pursued, every knowledge that previously had been won, and, above all, every method that was previously practiced and has supposedly proved its worth, must be thrown into the cauldron once again, delivered up to the living God, and proffered to him as a total sacrifice.

Theological work cannot be done on any level or in any respect other than by freely granting the free God room to dispose at will over everything that men may already have known, produced, and achieved, and over all the religious, moral, intellectual, spiritual, or divine equipage with which men have traveled. In the present continuation of what was won yesterday, the continuity between yesterday and today and between today and tomorrow must be submitted to God’s care, judgment, and disposing. Theology can only be a really free and happy science in a continually new performance of this voluntary offering. If it does not want to succumb to hardening of the arteries, barrenness, and stubborn fatigue, its work should at no step of the way become a routine or be done as if it were the action of an automaton. Because it has to be ever renewed, ever original, ever ready to be judged by God himself and by God alone, theology must be an act of prayer. The work of theology is done when nothing else is accomplished but the humble confession, ‘Not as I will, but as thou willest!’

It ought come as little surprise, therefore, to learn that Barth protested against attempts to found a theological school of thought or a ‘movement’ that might advance his own project. In this Barth was simply being true and consistent with his reformed conviction, for to be committed to the reformed project is not to be committed to being ‘Reformed’ but to being ‘Christian’ (albeit in a reformed kind of way) and to loving the church so much that you direct all your efforts towards her continual hearing of the Word of God rather than assuming that what you heard yesterday is the Word of God for today. The Word of God, in other words, is not an idea or words about an idea, but the dynamic person of God himself who in the freedom of grace makes himself available to us.

Some reformed theologians – Shirley Guthrie Jr., for example – have drawn attention to a double crisis within the tradition – a crisis of identity and of relevance. In some churches so much value is placed on identity – i.e., on adherence to tradition which is then often reduced to a series of propositional truths, etc. – that it often leads to the suppression of imaginative and critical thinking, and to the church becoming both exclusive and judgmental of those who think and live otherwise, and unable to respond creatively and effectively to rapidly changing circumstances. New information or perspectives are discounted in attempts to safeguard doctrine, polity or practice. In the end, it’s often simply about power.

At the other extreme, in a quest for relevance, some churches jettison tradition and historical memory altogether, losing their identity in the process. Abandoning or rendering superficial the resources of history, tradition, liturgy, and theology leaves churches vulnerable to cultural forces that promote idolatry. A church that has lost its memory is in a state akin to senility and prone to repeat the mistakes of the past. Henry Chadwick once made this point powerfully when in the midst of a debate at the Anglican Church’s General Synod (1988) he famously stated that ‘Nothing is sadder than someone who has lost his memory, and the church which has lost its memory is in the same state of senility’. A similar point was made by Simon Schama who, in responding to the lack of historical instruction in Britain’s secondary education, noted that ‘a generation without history is a generation that not only loses a nation’s memory, but loses a sense of what it’s like to be inside a human skin’. And Jinkins also writes:

When memory exits so goes our identity, our grasp on those particular and idiosyncratic recollections that make us who we are, that make us human, that hold us in relationship with one another, that not only make sense of our past but also orient us in the world. When memory fails us we are reduced to confusion. We cannot move forward because we have lost continuity with ourselves and with those who are closest to us. The question is why anyone – and more to the point I want to make – why any church would choose to jettison the memory that makes us who we are. Having loved and lost those who suffered from Alzheimer’s, how could any of us wish for such a fate to befall our church?

Once upon a time, of course, ‘Presbyterians simply looked like Presbyterians. They were clean and well starched. They went to Sunday school and believed in predestination’ (Alston). We may well wish to distance ourselves from such a caricature but there remains much value in our distinctiveness that takes us beyond the straitjacketed stereotypes. Correspondingly, we might think of the habitus, or character, of reformed Christianity in conjunction with its cultural-linguistic identity, a trait George Stroup characterises as ‘family resemblance’. Here, reformed identity is not so much an outdated stereotype, nor a set of theological-ecclesiological propositions, but a family photo album that spans several generations. While no two members of the family are identical, as you become familiar with the family it becomes possible to intuitively pick out a member of the family. [I am very grateful to one of my many amazing ex-students, Rory Grant, for pointing me to this article.]

We might think of such generational family resemblance as an artifact of the narrative history of the tradition – the reformed ‘look’ similar because they have a shared history. However, shared history does not automatically equate to a fixed set of criteria or attributes that define reformed identity. We need to think here of a tradition characterised by both continuity and diversity.

In my teaching, I am keen to assist students to understand and value the characteristics that make the reformed faith distinct. Among these characteristics are (i) a commitment to being a broad church, and (ii) our strong emphasis on education and, relatedly, an expectation of an educated clergy.

Certainly, the reformed tradition is – at its best – a broad tradition, captive to neither the left nor the right of the theological spectrum. The reformed believe that the politicising of the body of Christ along lines which limit the love and availability of God are a scandal against the Table of the Lord. One place we see such happening in our context here in New Zealand is where those associated with more progressive expressions of reformed faith and who dominated our General Assembly and college for over half a century now find themselves on the margins and struggling to find a place in a sea of more conservative expressions of the faith. Regardless of where one sees oneself on the theological spectrum, this situation constitutes an ongoing challenge to our identity historically conceived. Also, as in many other places, increasingly our ministers and congregations come from non-reformed backgrounds. This basic ignorance of reformed identity means a loss of connection with our past, and that leaves us more vulnerable to both repeat its mistakes, and not free to celebrate, learn from and build on its strengths.

Breadth also means taking seriously the cultural, ethnic and social diversity in the Presbyterian family, and a commitment to making the journey together. We are all so much the poorer without each other. Shall the toenail say to the belly-button, ‘I don’t need you’? We as a church are yet to find ways where our full ethnic diversity is both represented and celebrated. There are challenges here, to be sure – translating all the English material into Korean and vice versa, for example – but it’s worth taking up as a priority for the next Assembly, and at presbytery level too. We as a church are all so much the poorer without our breadth.

If what I have witnessed at the past two GAs is any indication of things, the trust barometer of the church is pretty low. And without trust, the divisions shall only widen, and harden. I have also witnessed a people who – on all sides of each debate – care deeply for the church, who love the church and who are invested in its betterment and in the betterment of its witness to God’s love in the world. We must all do better to widen that affection not only for our own patch, or for the church in the abstract, but for the actual people that God has made us family with. This road will require forgiveness, apart from which there will be no future for the PCANZ. The Christian does not carve out his or her own story ex nihilo, or even with the likeminded alone. Jesus does not grant us the liberty to choose our friends. Rather, whenever Jesus comes to us he always brings his friends along with him as well … and he helps us to love them, to stake our very existence on the claim that I simply cannot be me without them, hence the deep existential pain born of the great mistrust between Abel and Cain. Remain unconvinced? Read 1 John! ‘Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen. The commandment we have from him is this: those who love God must love their brothers and sisters also’. To this end, it is my hope that the PCANZ might learn here from our brothers and sisters across the ditch in the Uniting Church in Australia and embrace the consensus model of discernment at every level of its governance. Enough said.

On the question of education, we might simply note that education was fundamentally important in Grandpa Calvin’s church, and in the early reformed movement more widely. In Geneva, for example, this is evident through the emphases on catechesis and the ‘sermon’, and through the establishment, in 1559, of the Genevan Academy which became the nursery of reformed movements in France, the Netherlands and Scotland. In 1536, at a town meeting, the Genevans also voted to begin what is considered to be the first public-run school. Such a commitment betrays the reformed assessment of all creation thriving as both under the sovereign government of God and as the ‘theatre’ of God’s glory, and sponsors the reformed determination to engage in public theology. The church has always faced the temptation to disengage from the world, to take a turn inwards and focus almost entirely on ‘churchly’ or ‘spiritual’ matters. One response to this turn here in NZ has been to try to carve out a space in university departments for Christian theologians with a proven record and proficiency in the area of public theology to contribute in a constructive way to public discourse around issues facing our nation (e.g., domestic violence, restorative justice, climate change, foreign trade, etc.). These strategic positions sometimes need to be funded from church sources but the positions I have in mind in NZ are already proving to make an important contribution to public discourse, and to model for local churches how they might go about doing the same in their contexts. For example, Chris Marshall serves as Head of School of Art History, Classics and Religious Studies at Victoria University, a position initially fully-funded by a local church in Wellington. Also, the University of Otago has set up the excellent Centre for Theology and Public Issues which is headed up by Andrew Bradstock. One downfall of this model of subcontracting public theology to the university, however, is that it threatens to remove public theology from the life of the church. Does the church need to resurrect its Public Issues Committee, freshly conceived?

The matter of education also finds deep roots in the inclination of the reformed to insist on an educated and theologically-rigorous clergy and church. Historically, one of the real gifts that the reformed have bequeathed to the wider Church and to the discipline of theology has been the rigour with which it has undertaken the indispensable task of talking about God and about God’s work in the world. The twin temptations of abandoning this rigour and/or buying too uncritically into the humanist and enlightenment program with which it has sometimes been associated are real. But it is only to our detriment and – more importantly – to the detriment of the Church’s ongoing witness to Christ that the reformed would neglect this fundamental task. To speak of God in such a way that engages the real questions of our time is not a task for the faint-hearted or the frivolous.

Again, Jinkins:

One of the greatest gifts of the Reformed project is its commitment to the life of the mind in the service of God. From the first, Reformed Christians have sought to advance the best thinking in the face of superficiality, superstition, bad religion, social reactivity, and anxiety. As expressions of confidence that Christian faith and the promotion of knowledge go hand-in-hand, the Reformed project established the first programs of universal education, founding universities, graduate schools, and teaching hospitals as it moved across the world. Today the world’s problems have become extraordinarily complex, and many religious people try to prove their religious devotion by refusing to test their convictions intellectually or by seeking to silence those with whom they disagree. Now more than ever, we as Reformed Christians must foster the curiosity and intellectual openness that have driven us to think deeply, for there is desperate need for faithful people who are bold and unflinching thinkers, people who will use their best knowledge and concerted intellect to engage and mend a broken world.

So we are thinking here about the posture of the reformed to love God (and God’s world) with our mind, as well as with our heart, soul and strength. The reformed are typically those in the body of Christ who worry about what will become of Christian faith – and, indeed, of the world – if Christians fail to ask the tough, deep, critical, sometimes intractable questions about life. They are those who are ‘concerned about what it will mean for our faith if we choose to ignore life’s most profound mysteries and insoluble riddles’, who are ‘concerned about the integrity of the church if we abandon the curiosity that is unafraid to swim at the deep end of the pool, if we jettison a passion for ideas, for knowledge, and for wisdom for their own sake’ and who are equally ‘disturbed about what will become of society if persons of faith retreat from the public sphere, where ideas must fight for their lives among competing interests, where justice is served by vigorous argumentation and intelligent action as much as by high ideals’ (Jinkins). They are those who believe that the greatest heresy the church faces today is not atheism but superficiality, and its attendant ‘cult’. To cite Jinkins, again:

Occasionally I hear editors of church publications or church growth consultants arguing that Christian laypeople just aren’t interested in theology, or that laypeople aren’t interested in the history of their faith or, worse still, that laypeople simply can’t understand complicated ideas. Yet, when I speak in congregations around the country, I regularly encounter crowds of lively, intelligent laypeople hungry to know more about their faith. These are laypeople, incidentally, who in their daily lives run businesses and shape economies, teach, read or even write important books on a variety of serious subjects, argue legal cases before judges and juries, write laws that shape our common life, and cure our diseases of the mind and body. These laypeople are tired of being infantilized at church. They want to understand their faith more deeply.

The comments of the laypeople I meet, people who want to learn more about their faith, are often along the lines of what an elderly woman said … one Sunday after [Tom Long] had preached in one of the many congregations in which he speaks around the country. As he was making his way from the pulpit to the sanctuary exit, the woman stepped forward to greet him. Earlier in the evening, Tom had invited members of the congregation to share with him any messages they’d like him to take back to the future ministers he teaches in seminary. As this woman stepped forward, Tom greeted her with the question, ‘Is there a message you’d like me to take back to the seminary, something you’d like me to tell our students?’

‘Yes, there is,’ she said. ‘Tell them to take us seriously.’

Now, I know that not every person in our churches, or indeed in our society, craves to understand God (or anything else) more deeply. But I would also maintain that at the core of the gospel there is a sacred mandate – we call it the Great Commission – to go into all the world to make disciples, ‘teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you’ (Matt. 28:20). The word disciple translates a Greek word that means ‘pupil’ or ‘willing learner.’ As church leaders, then, we have this duty, this mission, this commission: to teach, to kindle curiosity, to expand knowledge, to renew minds, to make our people wiser. And there are many, many people only too eager to learn.

The reformed emphasis on the importance of education needs to be tempered, however, with the kind of humility that many reformed emphasise concerning human personhood in general, and about the noetic effects of the Fall in particular. Truth (as the saying goes) is the first casualty of war. But self-criticism is among the first casualties of insecurity, especially those brands of insecurity that transform thinking people into an unthinking herd.

Christian faith, on the other hand, thrives on a spirit that resists taking itself too seriously. As G. K. Chesterton once suggested, angels can fly because they take themselves lightly. Devils, on the other hand, fall under the weight of their own self-regard. Again, Jinkins:

A thinking faith is a self-critical faith. A thinking faith knows its own limits because it is guided by a comprehension of a basic reality: we are human. We are creatures. We are not God. Thinking faith’s recognition of human finitude generates reverence for transcendence and recognition of the limits even of its own claims.

Thinking faith is characterized as much by its humility and reticence as by its pronouncements. Along with its reverence for God and respect for others, it is characterized by a kind of irreverence toward its own certainty. One might regard thinking faith as a faith chastened by knowledge and experience. One would certainly regard thinking faith as a faith that has made its peace with ambiguity, because it cannot and it will not try to justify itself in the presence of God. But it is inevitable, for these very reasons, for a thinking faith to be thought ‘weak’ by some.

It has become commonplace in our culture for Christians to believe they can only prove their faith by claiming to know the mind of God. Yet, pretensions to certainty do not signal a superabundance of faith. They indicate, rather, faith’s vanity and paucity. Religious dogmatism is the child of insecurity.

All this is to say that it strikes me that there is something most foul and most un-reformed at work whenever a member of the reformed family of churches makes a decision to not keep engaging theologically, particularly with the very matters that it has just discerned are ‘fundamental’ to the Christian faith. That the recent GA made precisely such a decision (regarding NOM #133) strikes me as deeply disturbing.

The matters to which NOM #133 are inviting the church to engage are not black and white, but brim with doctrinal, pastoral, ecumenical and ecclesial implications, not least around the question of our relationship with the State. We are a people called to have our agenda set not by the State but by God’s good news announced in Jesus Christ – news which ought to inform and give shape to all our life together and to God’s vision for a society in which human personhood is radically reconstituted after the image of One whose hospitality is most irresponsible, surprising and risky. I consider NOM #133 to be an invitation – perhaps even an invitation by God – to pause and to ask deeper questions about our identity as creatures and as church, and to grow as a result. I am not sure that we as a church together have asked those questions yet in a mode that leaves us satisfied enough to move forward on this divisive issue in a way that gives due fidelity to the gospel and to the hard questions that the gospel raises for us. I can only hope that this desire will not rest, and that ministers and others will seek to bring the essence of NOM #133 to their respective presbyteries (and invite other presbyteries too) with a view to an invitation then being made to the much under-utilised Doctrine Core Group to do some work on this question for us all. The invitation for this important work need not come from the GA though the fruit might well serve that court of our church.

[Image by Diane Gilliam-Weeks. Used with permission]