But you misdoubt me, you pursue me, you press me. And you accuse me of theology. Revelation is a great word, you say. It suggests great things and powers–sea, hill, and sky, a world of living passionate men and women. And Redemption suggests old folios, dead and done with. You ask to know if we must confine revelation to Christ and the Cross with their systems and sermons, if it means but redemption, if it come home but by justification. Must we use these dry old schemes and names? Is there no language, no action of a more human and hearty kind for God and His ways, none of a kind more literary, and poetic, and sympathetic? Is revelation not a word too large for these shrunk theological terms? Is not all illumination revelation–the light of nature, of reason, of the heart? Is there no revelation in earth’s daily splendour around us, in heaven’s mighty glory above us, in the heart’s tender or tragic voice within US? The lover, the mother, the child, ‘the poet, the thinker, the hero—is there no revelation there? Oh, surely! It would be heartless and soulless to deny it. It would disqualify any man for discussing die subject. The inhuman heart is no expositor of the love of God. To sear our affections is no way to commend God’s. But after all, these things are but as moonlight unto sunlight.

“The sun at noon

To God is moon.”

They reveal a borrowed fight. The light they have comes from their reflection of the Sun of the soul–the Saviour. For, in the first place, they but suggest God rather than they assure Him to us. And what we want for our faith, to stake our eternal soul on, is absolute certainty. The matter of religion is God Himself in the soul; the result of it is certainty. And again, they suggest Him to individuals rather than make Him sure to a world. They appeal also to the pure ‘in heart rather than to the sinful soul, soiled and dark and outside God. You will come to a pass one day when the glorious world falls from you, the dearest must leave you, your nerve perhaps is broken, you have no witness of a good conscience, and your self–respect no more sustains you. Poetry and happiness, knowledge and sensibility, end perhaps in moral wreck. That is the time for real revelation. Man’s extremity is God’s great opportunity. Then, as never before, you need a light that does not fail. You need the revelation indeed, the one certainty for which you would exchange all the mere impressions you ever felt. And then, as when the first light arose, it rises with a new creation. God made us in order to understand His creative love; and so He must make us over again if we are to understand anything so tremendous, so incredible as His redeeming love, the gift of Himself and His mercy. It is beyond human power to believe in the mercy of a holy God when we need it most. just when you most need it, you cannot rise to it. If you could, you would not need it. It is a miracle. But when you do arrive there, then everything is a revelation. It is a new heaven–and a new earth. You go down to your new house justified.

True enough, we are led on from revelation to revelation as life presses and opens on us. But it is the final revelation that carries the secret and fixes the colours of them all. And is it not your justification?

What is the word to your conscience and its collapse?

What moral reserves are you laying up?

Do we not know the passion of knowledge, its joy, its glow; and the knowledge of passion, its fire and sting? Are the young among you not in the midst of it all? Have we not heard the message of the dim woods? And silent upon a peak have we never felt the appeal of the whole world lying in light at our feet? From a sunset the new Jerusalem has descended on us, adorned with all manner of precious stones. The breath of the breeze and the bloom of the flowers, dews in the valley and mist on the hill, cloud shadows lying lightly on long braes and murmuring stripies hidden among the heather–were such things no revelations to us of a kind in their time? Again, do we not know the joy of new truth, poetic beauty, the spell of grand ideals? Was the world not once crystalline for us in Shelley, opal in Tennyson, ruby in Rossetti? Was life not newly intimate for us in Shakespeare, and greatness majestic in Milton? Are we not touched any more by the divine thing in love’s young dream? Are we ignorant how it transfigures all the world and uplifts all the soul–all the colour of life in the heart of one pearl, all the wonder of it in the heart of one girl? Do we want to forget the wholeheartedness of our young hero– worship, when we found one man who seemed either to eclipse or glorify all the rest of Humanity? Or again, in the clash of living wins, the successful sense of power, the ruling word of conscience, had we no revelation of the crushing sense of loss and failure, does there come no suggestion of the Cross by which that mastery was won for ever? In the long tale of human history–its romance, its tragedy, its achievement, its fascination–is there no light that leaps out on us from there, nothing that makes us other men, nothing that opens up divine reaches of being? Is there no call of fife, clarion and trumpet, that takes us from the sensual world and an age without a name, and makes us thrill to the crowded hours of glorious life?

To come quite near home. How many a youth in the years of romance feeds his imagination in this, the loveliest and most romantic dry in the world? But the romance of Edinburgh is not in its beauty only, it is in its history, and all its history stands for. The glamour and tragedy of our Scottish past is there–a romantic Queen–Mariolatry it be comes to some who do not feel the mystic Mariolatry of the Queen of Rome at all. Such things enlarge and humanize the spell laid on us by the witchery of this city. All Scotland’s past is in it. And chiefly there is in it the Church of our people, which has made Scotland the best that she is, and sent out from Scotland the best she has done. Our sense of Scotland’s beauty rises to the sense of its old romance; and its historic romance passes upwards into its historic faith. The charm of earth turns the power of God. Nature rises to history and history to religion.

That is a parable of the way of the soul and its history– the revelation of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Thus. We begin with a romantic revelation. We go on to a historic. We end in a moral and spiritual. We begin with a romantic religion. We cherish an idealism for which nothing is too good to be true. All geese are swans, and every maid a queen. Every father must surely be to his children what ours is to us. And above all the Father of all.

We readily see a generous All–fatherhood brooding over the whole world. Nothing we think could be true which gave that the lie. And then. as our mind grows, our range grows. Knowledge comes of a vaster world. Idealism and poetry and all their glamour are enlarged by real contact with history. with life. Our idolatry of one or two people becomes the idealizing of the race. The charm of nature yields to the spell of all Humanity. Some people could take you to the very spot where at a certain hour the love of nature and home became love of humanity. The revelation is no more in the family but in history. And in the heart of history stands Christ, now more than the Jesus of heart and home. We believed in a universal Father; we now believe also in the Son. We believe in the Christ of the race. the Son of Man, the Man Divine. But we do not stop there. He becomes more than historic, he becomes a Son Eternal, the Son of God, a Son who never dies, never leaves us, a Son brought home in a Church. The Lord is the Spirit. The Holy God of Israel becomes the Holy Spirit of Christ, which makes me a sinner. We believe in a Father and Son who come down in the Spirit to our little door, in our Baptism, and home to our very soul by the saving Word. I perceive a message, a power, a salvation for me, individualized to me. We believe in the Holy Ghost. We believe in the will of the Eternal Father, the work of the historic Son, the Word, the Church of the Holy Ghost. The heart is no revelation for itself It is too fickle, treacherous.

“The best of what we are and feel, just God forgive.”

History is no revelation, with its awful anomalies, its cruel passions, its egoisms, its barren conflicts and their uncertain ends. Man realizes God more than Nature does, only to defy Him more.

‘I saw Him in the flowering of the field,

I marked Him in the shining of the stars,

But in his ways with men I found Him not.”

And Newman found history a scroll written over with mourning and lamentation and woe. The Revelation is not history, though it is in history. It is historic in the Son and in the Church, it is near and searching in the Holy Ghost.

We began seeking God, because we felt so able and so, sure to find Him. We end by serving Him, because He has sought and found us, disabled and unsure. We began with a love of justice, we end with a prayer for justification. We begin by willing and knowing, we end by being willed and known. “His will is our peace.”

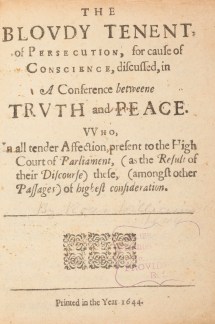

When, in 1644, the great Baptist pastor Roger Williams defended the claim that Christ is King alone over conscience ‘was and is the summe of all true preaching of the Gospell or glad newes’ (The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution), he was articulating a basic tenet of what it means to do faith in the Free Church tradition. He was also signalling that as noble as the human conscience is, its freedom is not achieved by its being made into an idol. Rather, the conscience is free – and faith is truly voluntaristic – only insofar as it recognises the final authority of Another.

When, in 1644, the great Baptist pastor Roger Williams defended the claim that Christ is King alone over conscience ‘was and is the summe of all true preaching of the Gospell or glad newes’ (The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution), he was articulating a basic tenet of what it means to do faith in the Free Church tradition. He was also signalling that as noble as the human conscience is, its freedom is not achieved by its being made into an idol. Rather, the conscience is free – and faith is truly voluntaristic – only insofar as it recognises the final authority of Another.

In his wonderful study,

In his wonderful study,