- Andy Goodliff draws attention to an upcoming conference – Nil Illegitimi Carborundum: A Conference on Theology, the Church, and Controversy – at the University of Aberdeen from 1–3 July, 2010. Speakers include Robert Jenson, Vigen Guroian, David Bentley Hart, Peter J. Leithart, Carl Trueman, John Webster, Laurence Hemming, Susan Frank Parsons, Markus Mühling, Peter McMylor, Francesca Murphy, and Brian Brock.

- Dave Kirkman rehearses some Calvin and Luther on Christ’s descent into hell.

- David Kerrigan turns to Brueggemann in order to challenge those of us who preach to recognise our calling to be poets in a world of prose.

- Debra Dean Murphy posts on Boutique Discipleship.

- Carl Trueman offers a thought-provoking reflection on Roman Catholicism.

- Mike Gorman is asking about NT introductions.

- Evan Kuehn offers some thoughts on Ryken’s appointment at Wheaton.

- Kent Eilers posts a wonderful excerpt of a sermon by Pannenberg.

- Matt Gerrelts asks ‘What does Hegel mean by Desire?’

- Scott Hamilton posts ‘in defence of brainwashing’.

- Ben Myers, who recently posted twelve wonderful theses on libraries and librarians, also reminds us that the Archbishop of Canterbury doesn’t just sit around and drink lots of tea.

- Steve Harris considers the Lutherans and Locke on faith and reason.

- Rick Floyd turns to Cyril of Alexandria to get some help with a sermon on Luke 13:31–35, and blogs on Is Cyberspace Evil? Thoughts Toward A Christian Ethic of Blogging.

- Finally, a good reflection by Rowan Williams, ‘Out of the abyss of individualism’: ‘… the importance of the family isn’t a sentimental idealising of domestic life; it is about understanding that you grow in emotional intelligence and maturity because of a reality that is unconditionally faithful. In religious terms the unconditionality of family love is a faint mirror of God’s unconditional commitment to be there for us. Similarly, the importance of imaginative life is not a vague belief that we should all have our creative side encouraged but comes out of the notion that the world we live in is rooted in an infinite life, whose dimensions we shall never get hold of. As for the essential character of human mutuality, this connects for me with the Christian belief that if someone else is damaged, frustrated, offended or oppressed, everyone’s humanity is diminished’. Read the rest here.

Author: Jason Goroncy

Andrew Root on (youth) ministry

Andrew Root is the Assistant Professor of Youth and Family Ministry at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is also the author of Relationships Unfiltered: Help for Youth Workers, Volunteers, and Parents on Creating Authentic Relationships, Revisiting Relational Youth Ministry: From a Strategy of Influence to a Theology of Incarnation, Children of Divorce, The: The Loss of Family as the Loss of Being, and The Promise of Despair: The Way of the Cross as the Way of the Church.

Andrew Root is the Assistant Professor of Youth and Family Ministry at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is also the author of Relationships Unfiltered: Help for Youth Workers, Volunteers, and Parents on Creating Authentic Relationships, Revisiting Relational Youth Ministry: From a Strategy of Influence to a Theology of Incarnation, Children of Divorce, The: The Loss of Family as the Loss of Being, and The Promise of Despair: The Way of the Cross as the Way of the Church.

In this 31 minute video, Andrew explains the difference between influence and place-sharing in youth ministry. What he says pertains to all ministry, not just that related to young people. You can also listen to the talk here.

Picking up some Hauerwas for Lent

There’s one wee book of Hauerwas’ that I purchased during the past year and never got around to reading, namely Cross-Shattered Christ: Meditations on the Seven Last Words (Brazos Press, 2004). Lent seemed like the right time to dig in. So I found me a quiet moment tonight and read it. Here’s a few passages that I sat with for a while:

There’s one wee book of Hauerwas’ that I purchased during the past year and never got around to reading, namely Cross-Shattered Christ: Meditations on the Seven Last Words (Brazos Press, 2004). Lent seemed like the right time to dig in. So I found me a quiet moment tonight and read it. Here’s a few passages that I sat with for a while:

‘Everyday death always threatens the everyday, but we depend on our death-denying routines to return life to normality’. (p. 26)

On Luke 23:43: ‘What does it mean to say these are criminals?’ (p. 38)

Citing Rowan Williams: ‘God is in the connections we cannot make’. (p. 39)

‘Our attempt to speak confidently of God in the face of modern skepticism, a skepticism we suspect also grips our lives as Christians, betrays a certainty inappropriate for a people who worship a crucified God’. (p. 40)

‘Our salvation is no more or no less than being made part of God’s body, God’s enfleshed memory, so that the world may know that we are redeemed from our fevered and desperate desire to insure we will not be forgotten’. (p. 44)

‘In spite of the current presumption that Christianity is important for no other reasin than that Christians are pro-family people, it must be admitted that none of the Gospels portray Jesus as family-friendly’. (p. 50)

‘Jesus’s being handed over, Jesus’s obedience even to the point of death, Jesus’s cry of abandonment makes no sense if this is not the outworking of the mystery called Trinity. This is not God becoming what God was not, but rather here we witness what God has always been … The cross, this cry of abandonment, is not God becoming something other than God, is not an act of divine self-alienation; instead this is the very character of God’s kenosis – complete self-emptying made possible by perfect love’. (pp. 62–3)

‘This is not a dumb show that some abstract idea of god appears to go through to demonstrate that he or she really has our best interest at heart. No, this is the Father’s deliberately giving his Christ over to a deadly destiny so that our destiny would not be determined by death’. (p. 63)

‘We try … to compliment God by saying that God is transcendent, but ironically our very notion of transcendence can make God a creature after our own hearts. Our idea of God, our assumption that God must possess the sovereign power to make everything turn out all right for us, at least in the long run, is revealed by Jesus’s cry of abandonment to be the idolatry it is … In truth we stand with Pilate. We do not want to give up our understanding of God. We do not want Jesus to be abandoned because we do not want to acknowledge that the one who abandons and is abandoned is God. We seek to “explain” these words of dereliction, to save and protect God from making a fool out of being God, but our attempts to protect God reveal how frightening we find a God who refuses to save us by violence’. (pp. 64–5)

‘If God is not in Mary’s belly, we are not saved’. (p. 76)

‘”It is finished” is not a death gurgle. “It is finished” is not “I am done for.” “It is finished” will not be, as we know from the tradition of the ordering of these words from the cross, the last words of Jesus. “It is finished is a cry of victory. “It is finished” is the triumphant cry that what I came to do has been done. All is accomplished, completed, fulfilled work. The work that is finished, moreover, is the cross. He will be and is resurrected, but the resurrected One remains the One crucified. Rowan Williams reminds us of Pascal’s stark remark that “Jesus will be in agony until the end of the world.” This is a remark that makes unavoidable the recognition that we live in the time between the times – the kingdom is begun in Christ but will not be consummated or perfected until the end of the world. Williams observes that Pascal’s comment on Jesus’s on-going agony is not an observation about the deplorable state of unbelievers; it is instead an exhortation to us, those who believe in Christ. It is an exhortation not to become nostalgic for a supposedly lets compromised past or take refuge in some imagined purified future, but to dwell in the tension-filled time between times, to remain awake to our inability “to stay in the almost unbearable present moment where Jesus is.”‘ (pp. 83–4)

‘We are told in John 1:18 that without the Son no one can see the Father. Von Balthasar, therefore, reminds us “when the Son, the Word of the Father is dead, then no one can see God, hear of him or attain him. And this day exists, when the Son is dead, and the Father, accordingly, inaccessible.” This is the terror, the silence of the Father, to which Jesus has committed himself, this is why he cried the cry of abandonment. He has commended himself to the Father so he might for us undergo the dark night of death. Jesus commends himself to the Father, becoming for us all that is contrary to God. Christ suffers by becoming the “No” that the salvation wrought by his life creates. Without Christ there could be no hell – no abandonment by God – but the very hell created by Christ cannot overwhelm the love he has for us’. (p. 97)

‘Christ had no Christ to imitate’. (p. 99)

… be the sailor’s friend, be the dolphin Christ

Last night, I was privileged to be part of a gathering at the First Church of Otago for the induction of Anne Thomson. Henry Mbambo recalled – with passion much too rarely evident in the Presbyterianism in my part of the world – God’s charge upon ministers to ‘preach the word’ and that those so charged will, at times, be tired and discouraged. And, I was introduced to Colin Gibson‘s delightful hymn, ‘Where the road runs out’:

Where the road runs out and the signposts end,

where we come to the edge of today,

be the God of Abraham for us,

send us out upon our way.

Lord, you were our beginning,

the faith that gave us birth.

We look to you, our ending,

our hope for heaven and earth.

When the coast is left and we journey on

to the rim of the sky and the sea,

be the sailor’s friend, be the dolphin Christ

lead us in to eternity.

Lord, you were our beginning …

When the clouds are low and the wind is strong,

when tomorrow’s storm draws near,

be the spirit bird hovering overhead

who will take away our fear.

Lord, you were our beginning …

Lenten Resources

Lent has begun. Those seeking Lenten resources might wish to visit the following places:

Lent has begun. Those seeking Lenten resources might wish to visit the following places:

- The Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand has Lenten resources available including services and meditations and Lenten Bible studies.

- The Anglican Diocese of Melbourne has published Walking with Jesus through Lent.

- The PC(USA) is promoting Like a Seed.

- Last year, I prepared some Lenten Studies on The Seven Words of the Cross, and some Lenten images on The Stations of the Cross. I have also previously-posted material here.

- Inhabiting the Cruciform God: Kenosis, Justification, and Theosis in Paul’s Narrative Soteriology by Michael Gorman.

- At the Cross: Meditations on People Who Were There by Richard Bauckham & Trevor Hart.

- Cross-Shattered Christ: Meditations on the Seven Last Words by Stanley Hauerwas.

- Between Cross and Resurrection: A Theology of Holy Saturday by Alan E. Lewis.

- Lent and Easter Wisdom from G.K. Chesterton: Daily Scripture and Prayers Together with G.K. Chesterton’s Own Words by The Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis and Friends.

- Lent and Holy Week by Thomas Merton.

- Death on a Friday Afternoon: Meditations on the Last Words of Jesus from the Cross by Richard John Neuhaus

- Show Me the Way: Daily Lenten Readings by Henri Nouwen.

- Seven Lasting Words: Jesus Speaks from the Cross by Christopher R. Seitz.

- Mysterium Paschale: The Mystery of Easter by Hans Urs von Balthasar.

- Leviticus (New International Commentary on the Old Testament) by Gordon J. Wenham.

- Lent for Everyone: Luke Year C by Tom Wright.

- Christ on Trial: How the Gospel Unsettles Our Judgement by Rowan Williams.

- Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel by Rowan Williams.

- Also worth (re)visiting are Williams’ Lent books for the last three years: Life Conquers Death: Meditations on the Garden, the Cross, and the Tree of Life by John Arnold (2008); Why Go to Church?: The Drama of the Eucharist by Timothy Radcliffe (2009); and Our Sound Is Our Wound: Contemplative Listening to a Noisy World by Lucy Winkett (2010).

Thinking with Calvin about the relationship between pulpit, font and table

I’ve just finished giving some lectures on Calvin, part of which consisted of some reflections on Calvin’s understanding of the relationship between pulpit, font and table. I recalled how when Calvin returned to Geneva in 1541, he sought to make the Lord’s Supper the defining centre of community life. His Catechism of the Church of Geneva, penned in 1545 (the year before Luther died), outlines Calvin’s notion that the institution of the signs of water, bread and wine was fashioned by God’s desire to communicate to us, and that God does this by ‘making himself ours’. The signs testify to divine accommodation, to God ‘teaching us in a more familiar manner that he is not only food to our souls, but drink also, so that we are not to seek any part of spiritual life anywhere else than in him alone’. But the signs are not only God’s. They are also human actions, faith’s testimony to the Church’s cruciform identity in the world, to its belonging, its ontology. Moreover, font and table remain places of privilege where believers expect to see, taste, hear and touch the Word’s carnality in ways not expected elsewhere. The drama performed around font and table constitutes the activity of the Church which, together with its pulpit, ‘proclaims the Lord’s death until he comes’. The sacraments ‘derive their virtue from the word when it is preached intelligently’. In his Short Treatise on the Lord’s Supper, written while in Strasbourg but with an eye on Geneva (where it was printed), Calvin further expanded themes introduced in his Strasbourg liturgy, notably a more christologically-determined epistemology and doctrine of assurance, and the claim that the ‘substance of the sacraments is the Lord Jesus’ himself:

I’ve just finished giving some lectures on Calvin, part of which consisted of some reflections on Calvin’s understanding of the relationship between pulpit, font and table. I recalled how when Calvin returned to Geneva in 1541, he sought to make the Lord’s Supper the defining centre of community life. His Catechism of the Church of Geneva, penned in 1545 (the year before Luther died), outlines Calvin’s notion that the institution of the signs of water, bread and wine was fashioned by God’s desire to communicate to us, and that God does this by ‘making himself ours’. The signs testify to divine accommodation, to God ‘teaching us in a more familiar manner that he is not only food to our souls, but drink also, so that we are not to seek any part of spiritual life anywhere else than in him alone’. But the signs are not only God’s. They are also human actions, faith’s testimony to the Church’s cruciform identity in the world, to its belonging, its ontology. Moreover, font and table remain places of privilege where believers expect to see, taste, hear and touch the Word’s carnality in ways not expected elsewhere. The drama performed around font and table constitutes the activity of the Church which, together with its pulpit, ‘proclaims the Lord’s death until he comes’. The sacraments ‘derive their virtue from the word when it is preached intelligently’. In his Short Treatise on the Lord’s Supper, written while in Strasbourg but with an eye on Geneva (where it was printed), Calvin further expanded themes introduced in his Strasbourg liturgy, notably a more christologically-determined epistemology and doctrine of assurance, and the claim that the ‘substance of the sacraments is the Lord Jesus’ himself:

Jesus Christ is the only food by which our souls are nourished; but as it is distributed to us by the word of the Lord, which he has appointed an instrument for that purpose, that word is also called bread and water. Now what is said of the word applies as well to the sacrament of the Supper, by means of which the Lord leads us to communion with Jesus Christ. For seeing we are so weak that we cannot receive him with true heartfelt trust, when he is presented to us by simple doctrine and preaching, the Father of mercy, disdaining not to condescend in this matter to our infirmity, has been pleased to add to his word a visible sign, by which he might represent the substance of his promises, to confirm and fortify us by delivering us from all doubt and uncertainty.

Calvin contended that ‘the singular consolation which we derive from the Supper’ is that it ‘directs and leads us’ to Christ, attesting to the truth that ‘having been made partakers of the death and passion of Jesus Christ, we have everything that is useful and salutary to us’. So in the 1536 edition of the Institutes, Calvin defines sacrament as ‘an outward sign’ which testifies to God’s grace, and which ‘never lacks a preceding promise but is rather joined to it by way of appendix, to confirm and seal the promise itself, and to make it as it were more evident to us’.

Calvin begins his Summary of Doctrine concerning the Ministry of the Word and the Sacraments with the statement that ‘The end of the whole Gospel ministry is that God, the fountain of all felicity, communicate Christ to us who are disunited by sin and hence ruined, that we may from him enjoy eternal life’. And Calvin proceeds to outline that this communication of Christ – which is both ‘incomprehensible to human reason’ and ‘effected by the Holy Spirit’ – is made possible because of God’s desire to ‘communicate himself to us’ through the same Spirit, and involves us being joined to Christ our Head, ‘not in an imaginary way, but most powerfully and truly, so that we become flesh of his flesh and bone of his bone’. This union is effected by the Spirit who, in Calvin’s words, ‘uses a double instrument, the preaching of the Word and the administration of the sacraments’. Moreover, Calvin imagines that the union of believers with Christ involves ‘two ministers, who have distinct offices’. There is (i) the ‘external minister’ who ‘administers the vocal word’ which is ‘received by the ears’ and ‘the sacred signs which are external, earthly and fallible’, and (ii) there is the ‘internal minister’, the Holy Spirit who ‘freely works internally’ to truly communicate ‘the thing proclaimed through the Word, that is Christ’.

Implicit here is the weight which Calvin places on the event of the Supper as a whole, and not just on the sacramental hosts. So Trevor Hart:

It is the ‘ceremony’ as such which constitutes the wider ‘sign’ within which the particular signifying power of bread and wine is located. And the ceremony is, of course, a synthesis in which objects, actions and words are juxtaposed and related to one another. So, while Calvin insists that the material signs are vital, he also refuses to detach their meaning from the accompanying immaterial symbolics of narrative. The bread and wine are ‘seals’ and ‘confirmations’ of a promise already given, and make sense only when faith apprehends them as such. There must therefore always be some preaching or form of words which interprets the ‘bare signs’ and enables us to make sense of them, and the ‘faith’ which apprehends them, while not mere intellectual assent, has nonetheless a vital cognitive dimension (Inst. IV.xvii.39) … This does not, it should be noted, reduce the elements to dispensable visual aids, as if the essential meaning of the Supper could be conveyed equally well in their absence. Calvin’s choice of similes is helpful here. Certain sorts of images (in our day we might cite photographic as well as painted images) may well require some verbal context before we can make appropriate sense of them, yet when viewed in this context they undoubtedly possess a power or force of their own which transcends the limits of meaning to which words alone may take us.

Clearly, for Calvin, the sacraments are essentially another form of the word. They are, after Augustine, the verbum visibile (‘a visible word’), ‘God’s promises as painted in a picture’ and set before our sight. They confer neither more nor less than the Word, and they have the same function as the Word preached and written: to offer and present Christ to us. They are, just as preaching is, the ‘vehicle of Christ’s self-communication … the signs are nothing less than pledges of the real presence [of Christ]; indeed, they are the media through which Christ effects his presence to his people’. And they constitute – no less than preaching – the Church’s ministry of the Word.

The separation of pulpit, font and table, and the prioritising of ‘words’ over the proclamation activities of baptism and eucharist, betray a failure to understand how these three particular activities might inform – and be informed by – theories of semiotics, ritual, dramaturgy and the sociology of knowledge. It is also, and more urgently, a failure to understand the nature and witness of Word in the Church’s ‘two marks’, and of the way the Spirit functions to create faith is us and to make us ‘living members of Christ’. And this has, consequently, sponsored both disproportion between word and sacrament, and a tendency towards binitarianism, both to the detriment of Reformed worship and ecclesiology. Certainly, preaching and the proclamation activities of font and table constitute two parts of the one action. A ‘low’ view of one results in a ‘low’ view of the other. As Joseph Small has noted: ‘If word and sacraments together are the heart of the church’s true and faithful life, neglect of one leads inexorably to deformation of the other, for when either word or sacrament exists alone it soon becomes a parody of itself … Reformed neglect of the sacraments has led to a church of the word alone, a church always in danger of degenerating into a church of mere words’. Why a community claiming to be concerned with the proclamation of God’s good news would neglect to taste the Word in the Supper each time it gathers to hear the Word expounded in human speech truly is an oddity.

While Calvin argued that ‘it would be well to require that the Communion of the Holy Supper of Jesus Christ be held every Sunday at least as a rule’, forlornly, many Reformed churches have propagated a situation wherein the pulpit and its associated wordiness have eclipsed the sacraments, sponsoring an arid intellectualism which has turned the worshipping community into ‘a class of glum schoolchildren’. It is not uncommon to witness Baptism’s reduction to little more than a welcoming ceremony, for the Supper to be celebrated infrequently, and even for fonts and tables to be discarded in favour of a pulpit which stands unbefriended in the centre of the chancel. In more appalling cases, the pulpit has joined font and table as relics on the sidelines, casualties of modernity’s techno gods.

Calvin, conversely, placed sacrament and word together at the heart of the community’s life not because he was a dreary traditionalist or obstructionist but because he ‘regarded as a settled principle that the sacraments have the same office as the Word of God: to offer and set forth Christ to us, and in him the treasures of heavenly grace’. In other words, pulpit, font, scripture and table function alike as witness to the Word who is the life of the world: (i) proclaiming in bold relief the gospel of Christ in whom we have true knowledge of God, and (ii) communicating Christ’s real presence to us, uniting us to Christ in the power of the Spirit ‘who makes us partakers in Christ’. So Calvin: ‘I say that Christ is the matter or (if you prefer) the substance of all the sacraments; for in him they have all their firmness, and they do not promise anything apart from him’.

I could have gone on (and on, and on) about Calvin, and to recall words from others too who further echo Calvin’s heart on these matters, but even lectures on Calvin must come to an end. Anyway, had I gone on, I may have invited reflection on these two passages:

‘[We understand] the sacraments as pieces of earthly stuff that are meeting places with this [triune] God who exists in ecstatic movements of love. They are doors into the dance of perichoresis in God. [They are a means] of God’s gracious coming and dwelling with us. They are signs which enable us to participate in the drama of death and resurrection which is happening in the heart of God. We share in death as we share in the broken body of the bread and the extravagantly poured out wine, and as we are covered with a threat of hostile waters. We share in life as we come out from under the waters … to take our place in the new community of the body of Christ, and to be filled with the new wine of the Spirit. – Paul S. Fiddes, Participating in God: A Pastoral Doctrine of the Trinity (London: Darton Longman & Todd, 2000), 281.

‘Both sacraments [Baptism and the Lord’s Supper] declare the gospel of participation in the perfect worship of the Son, who has accomplished what we could not accomplish. When we receive the bread and wine at the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, we echo the cry of Jesus on the cross: ‘It is finished!’ Christ has done what I could never do … But we do more than engage in a memorial service! The word anamnesis, which translates into remembrance, has rich meaning…[conveying] a sense of re-living the past as if it were real today … Not only do we participate in shared and thankful remembrance of Christ’s perfect self-offering on our behalf, but we also participate in Christ’s continuing self-offering of himself on our behalf. We do not remember just the Christ of history – we remember the living Christ today, and the Christ who carries us into the future … The sacrament powerfully draws past, present, and future together in the life of the faith-community’. – Graham Buxton, Dancing in the Dark: The Privilege of Participating in the Ministry of Christ (Carlisle: Paternoster, 2001), 137–8.

On writing book reviews

As someone who enjoys writing the odd book review, I was struck by this statement (re-)posted over at Mike Crowl’s blog:

As someone who enjoys writing the odd book review, I was struck by this statement (re-)posted over at Mike Crowl’s blog:

‘Over the years, I have come to find writing book reviews even more distasteful than reading them. Part of this is my own fault, for being one of those old-fashioned holdouts who still believes that you should actually read the book before reviewing it. Sometimes I am only into the first 20 pages of a 500-page book when it becomes painfully clear that this one is a real dog. The rest of the ordeal is like crossing the Sahara Desert – except that often there are no oases. True, the reviewer gets to slaughter the author in print at the end of it all, but this merely appeases the desire for revenge, which only real blood would satisfy’. – Thomas Sowell, Some Thoughts about Writing (Stanford: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, 2001), 21.

Can’t say that I’ve ever felt like ‘slaughter[ing] the author in print’, but there’s still a pile of books on my desk awaiting review, so …

On hospitality

Been thinking lately about how a theology of divine hospitality might better inform – and be informed by – pastoral practice, and then I came across this statement in Wolfgang Vondey’s fascinating book, People of Bread: Rediscovering Ecclesiology (New York: Paulist Press, 2008):

Been thinking lately about how a theology of divine hospitality might better inform – and be informed by – pastoral practice, and then I came across this statement in Wolfgang Vondey’s fascinating book, People of Bread: Rediscovering Ecclesiology (New York: Paulist Press, 2008):

‘The Old Testament presents a harsh condemnation of inhospitable behavior. God’s judgment of Sodom shows that hospitality is not simply a social obligation but also an expression of the personal, moral responsibility of God’s people to others as well as to God. Jerusalem’s unflattering comparison with Sodom reveals not only the consequences of neglecting to offer one’s bread to strangers; it also underlines the effort necessary to engage in deliberate interaction and fellowship with those who are not from among us. Abraham is commissioned to teach his descendents the way of God’s justice and righteousness exhibited in the offer of hospitality and the sharing of companionship with those in need. As descendants of Abraham, the Israelites are called to be a people of bread who extend their companionship to the world.

The repeated emphasis on the “alien” is a fundamental element of the sharing of bread in the Hebrew scriptures. The memory of God’s hospitality in Israel’s experience of the exodus, when the Israelites were aliens in the land of Egypt, proves to be the motivation for Israel’s own extension of hospitality. God showed hospitality to Israel when the people were strangers, aliens, and outcasts. Marginalized and reduced to slavery, the Israelites found that they were no strangers to God. Companionship with God did not remove Israel’s alien status in the land of Egypt. However, God’s display of hospitality provided an environment in which the Israelites could experience companionship with one another and with God in the fellowship of bread.

God’s extension of hospitality allowed Israel to understand the moral failures of their past in a new light. God’s provision of bread invited Israel to participate in the sharing of stories from their past, enjoying the unexpected solidarity and impartiality of the present, and anticipating an unprecedented opportunity for freedom in the future. God’s provision of bread accompanied an even more daring display of hospitality: the deliverance of Israel from a life of exploitation and oppression. The people of bread experienced their God as the ultimate host who delivered them from a life of alienation and elevated them to be God’s chosen nation.

The sharing of bread with the stranger introduces the fellowship (koinonia) of God’s people to the notion of hospitality, a community-building practice performed on the basis of what Alasdair MacIntyre calls the “virtues of acknowledged dependence.” This dependence comes in the form of both the freedom and the responsibilities of companionship. Those who are liberated from their alien existence through God’s companionship are set free to extend God’s hospitality to all those who have remained strangers in the world. The Old Testament makes the experience of marginality and alienation normative for an understanding of hospitality. The extension of hospitality forms a bridge between the host and the guest by removing from their relationship the boundaries that inhibit solidarity and equality. Companionship with the stranger becomes an instrument of liberation, solidarity, and transformation.

Hospitality as a liberating and transforming practice of companionship is always particular, never generic. The relationship between host and guest stands at the forefront of the particular challenge of hospitality. Abraham’s and Lot’s displays of humility to their guests illustrate the attitude and behavior characteristic of the host’s role. Standing at the threshold of his own community, the host rushes out to meet the strangers, extending the realm of his companionship to those he does not know and breaking the sphere of alienation. In honest humility, the host identifies himself as the servant of his guests, offering not a favor but a service to those who are now no longer strangers but masters. In turn, the guests accept the invitation and are liberated from their alien status to participate in the fellowship of bread with those who likewise do not remain strangers but have become companions. Both host and guest forsake their position in their own communities for the sake of companionship. Put differently, the primary motivation for hospitality is the vision to live in a world without strangers.

The ambiguity about the identity of host and guest is a particularly important element in an ethic of hospitality. As John Koenig states, hospitality refers “not to a love of strangers per se but to a delight in the whole host-guest relationship, in the mysterious reversals and gains for all parties that may take place.” The willingness to forsake one’s position in the community for the sake of strangers comes with an uncertain risk attached. This risk lies neither in the host nor the guests themselves but in the community in which the act of hospitality takes place. Defending one’s hospitality to strangers, in the midst of a community that does not participate in the companionship, can make the host a stranger as well. At that point, hospitality comes at a greater cost than companionship. The preservation of hospitality at all costs requires from the very beginning a willingness to forsake one’s social status, community, or class by identifying one’s whole life and being with the fate of the stranger. As Scott H. Moore remarks, “To invite the stranger into one’s home is to make that which is private public and to introduce what is public into the private.” The sharing of bread with the stranger remains the most tangible expression of the commitment to companionship and the execution of righteousness and justice beyond the realm of one’s own community.

The challenge of hospitality as a surrender of oneself is well illustrated in the example of God’s hospitality at the exodus. In the biblical texts, hospitality to strangers is portrayed from the very beginning as a theological relationship mirroring the human companionship with God: hospitality to others is hospitality to God. The bread shared with the stranger is a service directed ultimately to God. John Chrysostom placed particular emphasis on this aspect:

This is hospitality, this is truly to do it for God’s sake. But if you give orders with pride, though you bid him take the first place, it is not hospitality, it is not done for God’s sake. The stranger requires much attendance, much encouragement, and with all this it is difficult for him not to feel abashed; for so delicate is his position, that whilst he receives the favor, he is ashamed. That shame we ought to remove by the most attentive service, and to show by words and actions, that we do not think we are conferring a favor, but receiving one, that we are obliging less than we are obliged.

Chrysostom stressed the idea that the motivation for hospitality among God’s people is born not only out of an identification of oneself with the stranger but also out of an identification of the stranger with God. Hospitality is the challenge to see in the stranger also the presence of God. In other words, the Israelites are asked to share their bread with strangers not because they are a people of bread but because they are the people of God. The freedom of extending one’s companionship to the marginalized and outcasts of society is a gift from God that establishes a testing ground for hospitality in commemoration and imitation of God’s companionship with the world. Hospitality thus becomes a means of both service to the world and worship of God, as we are reminded in this third-century homily:

For if you really wish to worship the image of God, you would do good to humans, and so worship the true image of God in them … If therefore you wish truly to honor the image of God, we declare to you what is true; that you should do good to and pay honor and reverence to everyone, who is made in the image of God. You should minister food to the hungry, drink to the thirsty, clothing to the naked, hospitality to the stranger, and necessary things to the prisoner. That is what will be regarded as truly bestowed upon God.

For the people of God, the primary challenge of hospitality is not only to abide by the rules of social and economic equality and solidarity but also to acknowledge God as the recipient of their moral actions. The bread shared with the stranger is companionship with God extended to the world as a reflection of God’s justice and righteousness.

From an ecclesiological perspective, hospitality is an extension of the covenant relationship with God into the world. In the covenant, the people of bread acknowledge God as the God of hospitality. The premise and goal of all hospitality is God’s companionship with humankind. The bread shared with the stranger is God’s bread. More precisely, however, the biblical texts portray the people of God as a catalyst for the extension of God’s invitation to the world. Israel is singled out as a chosen nation based not on their own achievement but on God’s love (see Deut 7:7–8). Hospitality to the stranger is a reflection of God’s hospitality in Israel’s past, particularly the commemoration of the Passover as a celebration of the final and eternal liberation of God’s people. In this sense, Israel’s call to companionship is also a prophetic sign of God’s extended hospitality to the world in the future.” The promise of God’s eschatological hospitality remains connected to the image of bread: Israel’s bread will not fail, the produce of the ground will be rich and plenteous (see Isa 30:25; 51:14; 55:10–11). The people of God are commissioned “to share their bread” not only with one another but with the stranger, the Gentiles, the foreign nations who one day will partake in God’s fellowship of bread (see Isa 58:7; 60:10–13; Ezek 47:21–23). The sharing of God’s companionship makes God’s hospitality available to those who are still outside of God’s covenant and invites them to share in the eternal fellowship at God’s table.

The sharing of God’s bread introduces to the world the story of God’s people, redirecting the world to an experience of God’s hospitality, and opening up possibilities for companionship with God. The fourth-century bishop Ambrose of Milan reminds us that the hospitality of God’s people is seen as a recommendation of God and approval of God’s people in the eyes of the world. The biblical texts portray hospitality as a call to keep the doors open for the stranger and for God in order to share in solidarity, equality, and unity in the fellowship of bread. This invitation is an indication that God’s covenant ultimately extends beyond the nation of Israel to all of humankind. The God of hospitality asks the people of bread to forsake a life of indifference, self-centeredness, and isolation for the sake of companionship with those who are not of the same nation, race, gender, culture, or faith.

Significantly, God’s call to show hospitality to the world takes place in an environment of sin, violence, isolation, and hostility. The free and selfless display of hospitality provides a key for the establishment of God’s justice and righteousness in the world. God’s challenge to invite the alien and outsider is accompanied by the equally challenging command to remain distant from the transgression and wickedness of the world.

Do not intermarry with them, giving your daughters to their sons or taking their daughters for your sons, for that would turn away your children from following me, to serve other gods. Then the anger of the LORD would be kindled against you, and he would destroy you quickly. But this is how you must deal with them: break down their altars, smash their pillars, hew down their sacred poles, and burn their idols with fire. For you are a people holy to the LORD your God; the LORD your God has chosen you out of all the peoples on earth to be his people, his treasured possession. (Deut 7:3–6)

The concrete display of hospitality shows clear elements of both invitation and separation. The message of the Old Testament is to invite the stranger but to separate from Sodom. Hospitality is an invitation directed to the unprivileged and outcasts of society. The host exercises “the option or love of preference for the poor” by inviting them to find refuge and shelter among the people of God. On the other hand, hospitality provides an environment in which God’s justice and righteousness are established in the world. Host and guest are liberated to enter into companionship with one another and with a holy God. In this way, they become companions to each other but strangers to the world. Ultimately, the display of hospitality serves an act of separation of both host and guest from unrighteousness and sin.

Finally, the notion of hospitality reveals that the execution of God’s justice and righteousness is not restricted to a sinful world but is equally directed at God’s people. Those who were once strangers are called to forsake but not to forget their alienation and oppression. God’s people are motivated to companionship with the oppressed, the poor, and the stranger because they have experienced oppression, poverty, alienation, and sin but no longer participate in them. For those who were once persecuted it is a moral imperative to display hospitality to those who continue to suffer persecution. Morality, then, is the function of life in which the self-centered person extends an invitation to include others in his or her life. Together, host and guest enter a realm of hospitality in which shared moral action can be established on the basis of companionship with God. The call of God’s people to show hospitality is not simply a call to still the hunger of the world but to invite a divided world into a holy and consecrated companionship with God. God’s provision of bread thus remains a testing ground for the solidarity of God’s people with the fate of the world.

The New Testament emphasizes the social and moral responsibility of God’s people with particular force and infuses the challenge of hospitality with further meaning. In the community of the first Christians, the significance of companionship with God and the world is emphasized and transformed by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The image of bread in the Gospels hearkens back to the meaning of bread as a representation of the human relationship with God and with one another and finds its climax in the identification of the bread with the body of Christ. In the celebration of the Lord’s Supper, the human and divine extension of hospitality merge into one gracious invitation to participate in the sharing of the bread of life’. (pp. 97–104)

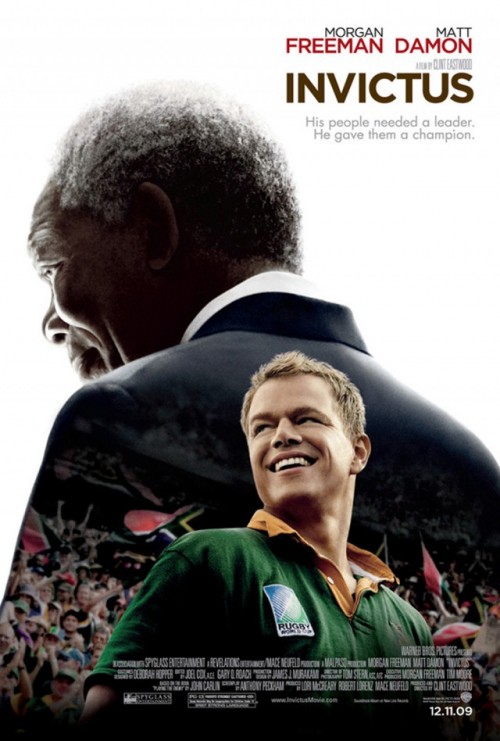

Why the Oscars are a con

‘This year’s Oscar nominations are a parade of propaganda, stereotypes and downright dishonesty. The dominant theme is as old as Hollywood: America’s divine right to invade other societies, steal their history and occupy our memory. When will directors and writers behave like artists and not pimps for a world-view devoted to control and destruction?

‘This year’s Oscar nominations are a parade of propaganda, stereotypes and downright dishonesty. The dominant theme is as old as Hollywood: America’s divine right to invade other societies, steal their history and occupy our memory. When will directors and writers behave like artists and not pimps for a world-view devoted to control and destruction?

I grew up on the movie myth of the Wild West, which was harmless enough unless you happened to be a Native American. The formula is unchanged. Self-regarding distortions present the nobility of the American colonial aggressor as a cover for massacre, from the Philippines to Iraq. I only fully understood the power of the con when I was sent to Vietnam as a war reporter. The Vietnamese were “gooks” and “Indians”, whose industrial murder was preordained in John Wayne movies and left to Hollywood to glamourise or redeem.

I use the word murder advisedly, because what Hollywood does brilliantly is suppress the truth about America’s assaults. These are not wars, but the export of a gun-addicted, homicidal “culture”. And when the notion of psychopaths as heroes wears thin, the bloodbath becomes an “American tragedy” with a soundtrack of pure angst …

My Oscar for the worst of this year’s nominees goes to Invictus, Clint Eastwood’s unctuous insult to the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Based on a hagiography of Mandela by a British journalist, John Carlin, the film might have been a product of apartheid propaganda. In promoting the racist, thuggish rugby culture as a panacea of the “rainbow nation”, Eastwood gives barely a hint that many black South Africans were deeply embarrassed and hurt by Mandela’s embrace of the hated springbok symbol of their suffering. He airbrushes white violence – but not black violence, which is ever present as a threat. As for the Boer racists, they have hearts of gold, because they “didn’t really know”. The subliminal theme is all too familiar: colonialism deserves forgiveness and accommodation, never justice. At first I thought Invictus could not be taken seriously, but then I looked around the cinema at young people and others for whom the horrors of apartheid have no reference, and I understood the damage such a slick travesty does to our memory and its moral lessons. Imagine Eastwood making a happy-Sambo equivalent in America’s Deep South. He would not dare’. – John Pilger

Read the rest here.

Hans Küng on Global Ethics, Roman Catholicism, and other stuff

Last night, Rachel Kohn, presenter of ABC Radio’s The Spirit of Things, aired an interesting interview with the Roman Catholic theologian Hans Küng. Among other things, they discussed global ethics (‘a program which can integrate again secularists and clericalists’), Roman Catholicism under Benedict (that ‘the Catholic church is in a period of roman restoration’) and genital mutilation. You can also download/listen to the conversation here.

John Webster on T.F. Torrance on Scripture [updated]

In his recent lecture on ‘T.F. Torrance on Scripture’ (presented in Montreal, 6 November 2009, at the Annual Meeting of the T.F. Torrance Theological Fellowship), Professor John Webster argued that Torrance’s most sustained writing on Scripture lay not in extended cursive exegesis but rather in ‘epistemological and hermeneutical questions – in giving a theological account of the nature of the biblical writings and of the several divine and human acts which compose the economy of revelation’ (p. 1). Such an account requires the theologian to both develop an anatomy of modern reason, in order to expose a ‘damaging breach in the ontological bearing of our minds upon reality’ (Reality & Evangelical Theology, 10), and to make an attempt at ‘repairing the ontological relation of the mind to reality, so that a structural kinship arises between human knowing and what is known’ (ibid., 10). Webster contends that Torrance’s writings on these matters constitute ‘one of the most promising bodies of material on a Christian theology of the Bible and its interpretation from a Protestant divine of the last five or six decades – rivalled but not surpassed’, Webster suggests, ‘by Berkouwer’s magisterial study Holy Scripture’ (p. 1).

In his recent lecture on ‘T.F. Torrance on Scripture’ (presented in Montreal, 6 November 2009, at the Annual Meeting of the T.F. Torrance Theological Fellowship), Professor John Webster argued that Torrance’s most sustained writing on Scripture lay not in extended cursive exegesis but rather in ‘epistemological and hermeneutical questions – in giving a theological account of the nature of the biblical writings and of the several divine and human acts which compose the economy of revelation’ (p. 1). Such an account requires the theologian to both develop an anatomy of modern reason, in order to expose a ‘damaging breach in the ontological bearing of our minds upon reality’ (Reality & Evangelical Theology, 10), and to make an attempt at ‘repairing the ontological relation of the mind to reality, so that a structural kinship arises between human knowing and what is known’ (ibid., 10). Webster contends that Torrance’s writings on these matters constitute ‘one of the most promising bodies of material on a Christian theology of the Bible and its interpretation from a Protestant divine of the last five or six decades – rivalled but not surpassed’, Webster suggests, ‘by Berkouwer’s magisterial study Holy Scripture’ (p. 1).

Webster devotes the bulk of his paper to three related areas of Torrance’s thought on Scripture: namely, that (i) Scripture must be ordered from a trinitarian theology of revelation; (ii) that the biblical writings are complex textual acts of reference to the Word of God; and (iii) that the Bible directs its readers to ‘a hermeneutics of repentance and faith’ (p. 4).

On this first point, Webster notes that ‘a theological account of the nature of Scripture and its interpretation takes its rise … not in observations of the immanent religious and literary processes, as if the texts could be understood as self-articulations on the part of believing communities, but in the doctrine of the self-revealing triune God. Torrance is unhesitatingly and unrelentingly a positive dogmatician at this point, in a couple of senses. First, and most generally, he takes revelation as a given condition for the exercise of theological intelligence, not as a matter about which intelligence is competent to entertain possibilities or deliver a judgment … Second, more specifically, Torrance’s positivity concerns the way in which knowledge of God, including knowledge of God through Holy Scripture – arises from the specific modes in which God deals with rational creatures’ (pp. 4–5). In support of this claim, Webster cites from (among other sources) Torrance’s Divine Meaning:

‘The source of all our knowledge of God is his revelation of himself. We do not know God against his will, or behind his back, as it were, but in accordance with the way in which he as elected to disclose himself and communicate his truth in the historical theological context of the worshipping people of God, the Church of the Old and New Covenants. That is the immediate empirical fact with which the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New testaments are bound up’ (Divine Meaning, 5).

Such a move, Webster recalls, enables Torrance to develop an account of revelation in which the relation of divine communication to the biblical texts is not fundamentally problematic, but rather is one in which ‘creaturely media can fittingly perform a service in relation to the intelligible speech of God’ (p. 6). He continues:

‘It was this, perhaps more than any other factor, which led to his estrangement from mainstream British theological culture, preoccupied as it was both in biblical and doctrinal work with the supposedly self -ontained realities of Christian texts, beliefs and morals, struggling to move beyond historical immanence, and weakened by a largely inoperative theology of the incarnation. Torrance was able to overcome the inhibitions of his contemporaries by letting a theology of the divine economy instruct him in the way in which God acts in the temporal and intelligible domain of the creature’. (p. 6)

Webster proceeds to note that the ultimate ground of Torrance’s claim that only God speaks of God is the Word’s assumption of flesh, an event which ‘carries with it the election and sanctification of creaturely form’ (p. 7). He concludes the section by underscoring Torrance’s refusal to be ‘trapped either by the kind of revelatory supernaturalism in which the Bible is unproblematically identical with the divine Word, and so effectively replaces the hypostatic union, or the kind of naturalism in which the Bible mediates nothing because it has been secularised as without residue a product or bearer of immanent religious culture’ (p. 8).

In the next section, Webster recalls how for Torrance the relation between the divine Word and the human words of Scripture is a positive one: ‘there is no crisis about the possibility of human text acts serving in God’s personal activity of self-presentation to intelligent creatures’ (p. 9). At this point the doctrine of Scripture exhibits similar formal features as does that of the hypostatic union. And Webster goes on to identify three ways in which Torrance amplifies this basic proposal: (1) Scripture as an accommodated divine Word (a theme that betrays Torrance’s indebtment to Calvin); (2) Scripture as sacrament; (3) Scripture’s expressive or referential relation to the divine Word. On the first, divine accommodation, Webster writes:

‘A theology of accommodation is a way of overcoming the potential agnosticism or scepticism which can lurk within strong teaching about the ineffable majesty of God. Doctrines of divine transcendence can paralyse theological speech, severing the connection between theologia in se and theologia nostra, and cause theology either to retreat into silence or to resign itself to the referential incapacity of secular human words. If, however, we think of divine revelation actively accommodating itself to creaturely forms, we make use of language about divine action, but without the assumption that divine action can only be efficacious an trustworthy if it is direct and immediate, uncontaminated by any created element. We retain, that is, a measure of trust that divine communicative activity is uninhibited by creaturely media, which it can take into its service and shape into fitting (though never wholly adequate) instruments. In terms of the doctrine of Holy Scripture, this means that, although we do not receive the Word of God directly but only ‘in the limitation and imperfection, the ambiguities and contradictions of our fallen ways of thought and speech’ (Divine Meaning, 8), nevertheless we do have the divine Word. Creaturely limitation, imperfection, ambiguity and contradiction do not constitute an unsurpassable barrier to the Word as it makes itself present to created intelligence … Divine appropriation, moreover, brings with it the transformation of creaturely speech, its transposition into a new field of operation and its being accorded a new set of semantic functions’ (pp. 11, 13).

In the next section, Webster turns to the question of biblical interpretation, where he allows the agenda to be set by Torrance’s own questions; namely, What is biblical interpretation’s most characteristic posture before the divine Word? What is the general tenor of its activity? From whence does it come, and to what end does it move? How does it come to learn to dispose itself fittingly in the domain of the divine Word? Webster recalls that for Torrance, the governing rule for the interpretation of Scripture is that the Scriptures ‘are to be interpreted in terms of the intrinsic intelligibility given them by divine revelation, and within the field of God’s objective self-communication in Jesus Christ’ (The Christian Doctrine of God, 43). He later cites from Torrance’s brilliant Reality & Evangelical Theology, noting that for Torrance theological interpretation is, therefore, a matter of ‘subjecting the language used to the realities it signifies and attend[ing] to the bearing of its coherent patterns upon the self-revelation of God which it manifestly intends’ (Reality & Evangelical Theology, 117). Webster concludes that ‘because of this, hermeneutics is not a poetic activity. The interpreter is not a co-creator of meaning by the work which he or she undertakes with the text. And so, in biblical hermeneutics the interpreter’s task is more than anything to receive with the right kind of pliability the gift of meaning which the divine Word extends through the text’s service. It is this all-important alertness to the text’s relation to the reality which it signifies which constitutes the scientific character of biblical hermeneutics … If the all-important property of the Bible is the semantic relation between divine Word and created text, the all-important hermeneutical activity is that of probing behind or beneath literary phenomena in order to have dealings with that which the phenomena indicate. The “depth – surface” language, that is, goes hand in hand with what has already been said of Scripture as sign or sacrament: the movement of which the Bible is part does not terminate in itself, and the interpreter must not be arrested by the merely phenomenal, but instead press through the text to the Word of which it is the ambassador’ (p. 16, 17).

A gravely important point. Webster does not, unfortunately, unpack the claim about poetic activity, nor does he proceed to relate this directly to preaching, and to what sense (if any) preaching – and, indeed, the Church’s entire liturgical witness – entails poetic action, that divine speech in Scripture calls not only for ‘crucifixion and repentance’ (Divine Meaning, 8) but also for a rigorous affirmation of the imagination, not as, to be sure, a ‘co-creator of meaning’ or where readers and hearers might be said to ‘make’ meaning, but as part of the Word’s faithful and sanctifying unveiling. Is imagination somehow not included in the claim, made earlier, that the Word’s assumption of flesh ‘carries with it the election and sanctification of creaturely form’ (p. 7)? I think here of Brueggemann’s Finally Comes The Poet, of Nicholas Lash’s Holiness, Speech and Silence (see, for example, pp. 3–4), and, indeed, of Torrance’s own The Mediation of Christ. Unless I have misunderstood Webster here, surely this is a matter of both/and. So Trevor Hart:

‘We must insist, to be sure, that God’s self-revealing initiative (in Scripture, in his own self-imaging in his Son, and in his personal indwelling of the church in his Spirit) be taken absolutely seriously and accounted for adequately in Christian discipleship and theological construction. Yet we must also acknowledge the vital roles played by imagination in laying hold of the reality of this same God and in enabling our response to God’s engagement with us. For faith, as evangelicals above all know very well, is a relationship with God that transforms and transfigures. It is a relationship in which the Father’s approach in Word and Spirit calls forth from us ever and again imaginative responses as we seek to interpret, to “make sense” of, and to correspond appropriately with what we hear God saying to us. It is not a matter of having a divine image impressed on us like tablets of wax but of having our imagination taken captive and being drawn into a divine drama, playing out the role that the Father grants us in the power of the Spirit, whom he pours out on the entire group of players’. – Trevor A. Hart, ‘Imagining Evangelical Theology’, in Evangelical Futures: A Conversation on Theological Method (ed. J. G. Stackhouse, Jr.; Grand Rapids/Leicester/Vancouver: Baker Books/Inter-Varsity Press/Regent College Publishing, 2000), 197–8.

Professor Hart, who has, I think, engaged with these questions more deeply and more satisfactorily than most in recent centuries, has argued elsewhere that imagination remains a key category for any discourse about themes eschatological, that in order to make sense of the kind of hopeful living towards God’s future that Scripture bears witness to demands that we take the imagination seriously. ‘One of the key functions of imagination is the presentation of the otherwise absent. In other words, we have the capacity through imagination to call to mind objects, persons or states of affairs which are other than those which appear to confront us in what, for want of a better designation, we might call our “present actuality” (i.e. that which we are currently experiencing). I do not say “reality” precisely because the real itself may well prove to be other than what appears to be actual’. He continues: ‘Another key role of imagination in human life is as the source of the capacity to interpret, to locate things within wider patterns or networks of relationships which are not given, but which we appeal to tacitly in making sense of things. We see things as particular sorts of things, and this is, in substantial part, an imaginative activity. And, since more than one way of seeing or taking things is often possible, what appears to be the case may actually change with an imaginative shift of perspective, rendering a quite distinct picture of the real’. – Trevor Hart, ‘Imagination for the Kingdom of God? Hope, Promise, and the Transformative Power of an Imagined Future’ in God Will Be All In All: The Eschatology of Jürgen Moltmann (ed. Richard Bauckham; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2001), 54. In other words, the present, Hart insists, does not contain its full meaning within itself, but only in its relation to what is yet to come.

It is precisely imagination, the capacity which is able to take the known and to modify it in striking and unexpected ways, which offers us the opportunity to think beyond the limits of the given, to explore states of affairs which, while they are radical and surprising modifications of the known, are so striking and surprising as to transcend the latent possibilities and potentialities of the known. If, therefore, the promise of God is the source of hope, it may be that we must pursue the suggestion that it is the imagination of men and women to which that promise appeals, which it seizes and expands, and which is the primary locus of God’s sanctifying activity in human life. (Hart, ‘Imagination’, 76)

Returning back to Torrance (and to Webster), it seems to me that the graced value of the imagination is not necessarily excluded from Torrance’s own rigorous scientific method, though, as Tony Clark has argued in a 2006 paper given at St Mary’s College, St Andrews, Torrance does have a tendency to see the scientific nature of theology as an exclusive paradigm for theological knowledge and in this the Scottish Presbyterian ‘discounts or marginalises other approaches to theology which ought properly to complement the “scientific model”’. [BTW: I heartily commend the published version of Clark’s PhD thesis, Divine Revelation and Human Practice: Responsive and Imaginative Participation]. If Webster’s point that hermeneutics is not a poetic activity is simply to underscore the basic unilateral givenness of the text then I can have no problem with his statement, but if by this claim he means to suggest that ‘the scientific character of biblical hermeneutic’ takes place apart from human imagination, then I would want to suggest otherwise.

To be sure, Webster touches on something of this in the final section of his lecture wherein he alludes to ‘a theology of the Word’s majestic freedom and condescension in appropriating and adapting created speech to revelation’ (p. 24), but he leaves this point undeveloped, electing instead to focus on Torrance’s trumpeting of ‘a genealogy of exegetical and interpretative reason … not only to give a pathology of hermeneutical defect but also to retrieve a set of useable dogmatic, metaphysical and spiritual principles by which to direct the interpretative exercise’ (p. 25).

My relatively-small reservation aside, Professor Webster’s paper is a superb introduction to Torrance on Scripture, and betrays his own longlasting engagement with questions of Scripture and hermeneutics, most obviously in Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch but also in other places. It certainly rekindled my appetite for Webster’s own forthcoming commentary on Ephesians (as part of the Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible series). Many thanks to the TF Torrance Theological Fellowship for making Professor Webster’s paper widely available.

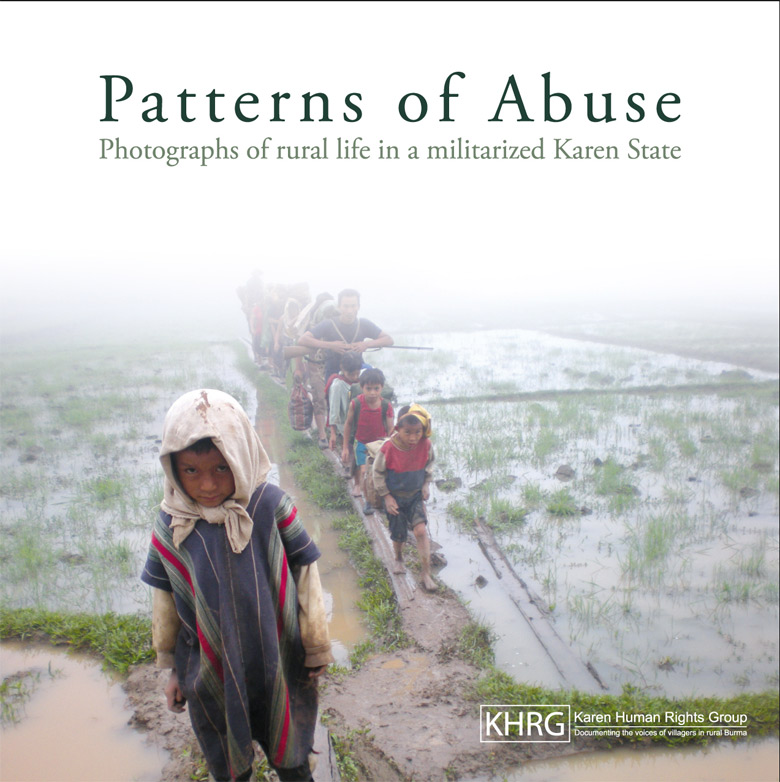

Patterns of Abuse: Photographs of rural life in a militarized Karen State

I have sometimes used this blog to draw attention to the humanitarian abuses facing Karen and Burmese people, two people groups most dear to me. And a few weeks ago, I mentioned that the Karen Human Rights Group (whose important work focuses on the human rights situation of villagers in rural Burma) has produced a 98-page photo-annotated album called Patterns of Abuse: Photographs of rural life in a militarized Karen State. This nicely-produced book contains 125 images taken over a 17-year period and depicts life in rural Karen State. My copy of the book arrived in our mailbox yesterday, and it powerfully documents the most tragic of human rights abuses against a most resilient people living under – and resisting – one of the most oppressive and evil regimes in history. A well-written introduction presents an accurate survey of the historical and political context that the Karen face, and subsequent sections illustrate and describe village life in Karen State, life in State Peace and Development Council-Controlled areas, life in non State Peace and Development Council-Controlled areas, as well as sections on soldiers and various portraits.

I have sometimes used this blog to draw attention to the humanitarian abuses facing Karen and Burmese people, two people groups most dear to me. And a few weeks ago, I mentioned that the Karen Human Rights Group (whose important work focuses on the human rights situation of villagers in rural Burma) has produced a 98-page photo-annotated album called Patterns of Abuse: Photographs of rural life in a militarized Karen State. This nicely-produced book contains 125 images taken over a 17-year period and depicts life in rural Karen State. My copy of the book arrived in our mailbox yesterday, and it powerfully documents the most tragic of human rights abuses against a most resilient people living under – and resisting – one of the most oppressive and evil regimes in history. A well-written introduction presents an accurate survey of the historical and political context that the Karen face, and subsequent sections illustrate and describe village life in Karen State, life in State Peace and Development Council-Controlled areas, life in non State Peace and Development Council-Controlled areas, as well as sections on soldiers and various portraits.

That neighbouring-Thailand’s welcome increasingly seems to be running dry only adds to the deep sense of anxiety that the 133,000+ Karen refugees experience, an anxiety further fed by the increasing sense of donor fatigue over a prolonged refugee crisis.

Please consider purchasing a copy. All proceeds support the work of KHRG.

Two worthwhile pieces on ministry

1. Kate Murphy reflects on whether youth ministry is killing the church:

1. Kate Murphy reflects on whether youth ministry is killing the church:

‘when our children and youth ministries ghettoize young people, we run the risk of losing them after high school graduation … I think I’ve done youth ministry with integrity. But I may have been unintentionally disconnecting kids from the larger body of Christ. The young people at my current congregation—a church that many families would never join because “it doesn’t have anything for youth”—are far more likely to remain connected to the faith and become active church members as adults, because that’s what they already are and always have been’.

2. Joseph Small (who is no stranger to this blog) on why ‘clergy’ and ‘laity’ ought be dropped from all Presbyterian usage:

‘Clergy and laity are two words that should never escape the lips of Presbyterians … Ministry within the church needs to be the responsibility of all the leaders — deacons, elders and pastors … Deacons, Small noted, have too often been relegated to serving coffee on Sunday and sending flowers to shut-ins … Elders “have become the board of directors of a small community service organization.” And … “What happened to ministers? They became clergy,” and clergy have ’emerged as the power in the church.” The divided role of ordained leadership in the church needs to change … and the walls between ordained offices torn down. Deacons are called to “leading the whole church in the ministry of compassion and justice … Elders should ‘share equally in the administration of the ministry of word and sacrament,” … [and] the “primary role” of ministers should be that of “teacher of the faith.”

Small said he favors use of the terms “teaching elders” and “ruling elders.” But … “ruling does not mean governing.” The correct meaning … “is rule like a measuring stick.” Ruling elders measure the congregation’s “fidelity to the gospel” and the “spiritual health of the congregation.” Small called ordained leaders in the church to be “genuine colleagues in ministry.”

Without collegial ministry, he said, the position of pastor becomes one of a lonely leader. He described the history of ministers in the United States as one of accumulated roles, where responsibilities always have been added but never withdrawn. Beginning on the frontier, Small said, pastors were called to be revivalists to “inspire and uplift.” When small towns grew on the prairie, the ministers were still expected to “know more about the faith,” but in addition to being inspirational preachers, ministers were expected to be community builders. As small towns grew into cities, ministers, he said, were expected to also be therapists, who helped those in the congregation “cope” with new stress.

As cities grew, ministers became “managers of an increasingly complex social organization called the church,” and today a pastor is expected to be a entrepreneur and innovator. “It’s just one more layer added on …’.

Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part IX, On Lutherans

We’ll make this the final post on Lischer’s, Open Secrets. Fittingly, it’s on Lutherans:

We’ll make this the final post on Lischer’s, Open Secrets. Fittingly, it’s on Lutherans:

‘Lutherans fill their vacancies more deliberately than any of the churches in Christendom. Vacant congregations go months without thinking about choosing a new leader, and pastors, once they have received a call, may sit on it for additional months before hatching a decision. The time isn’t used for negotiating more favorable terms; it is simply filled with prayer and dormancy. The President-elect of the United States names a Cabinet faster than the smallest Lutheran congregation picks a pastor, because Lutherans consider the latter process far more important. All is left to prayer and the brooding of the Spirit, and everyone knows the Spirit always works slowly’. – Richard Lischer, Open Secrets: A Memoir of Faith and Discovery, 220.

Here’s a list of the earlier posts:

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part I, On Theological Education

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part II, On Theological Education 2

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part III, On Homiletical Gridlock

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part IV, On the Trinity

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part V, On Symbols and National Flags

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part VI, On Gossip

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part VII, On the Church Calendar

- Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part VIII, On Abortion

A Script to Live (and to Die) By: 19 Theses by Walter Brueggemann

These 19 theses by Walter Brueggemann are the most interesting thing I’ve read all day [to be sure, it’s been a bit of an admin marathon today], an encouraging invitation to those of us striving to live by, and to train others to live by, what Brueggemann calls ‘the alternative script’:

These 19 theses by Walter Brueggemann are the most interesting thing I’ve read all day [to be sure, it’s been a bit of an admin marathon today], an encouraging invitation to those of us striving to live by, and to train others to live by, what Brueggemann calls ‘the alternative script’:

1. Everybody lives by a script. The script may be implicit or explicit. It may be recognised or unrecognised, but everybody has a script.

2. We get scripted. All of us get scripted through the process of nurture and formation and socialisation, and it happens to us without our knowing it.

3. The dominant scripting in our society is a script of technological, therapeutic, consumer militarism that socialises us all, liberal and conservative.

4. That script (technological, therapeutic, consumer militarism) enacted through advertising and propaganda and ideology, especially on the liturgies of television, promises to make us safe and to make us happy.

5. That script has failed. That script of military consumerism cannot make us safe and it cannot make us happy. We may be the unhappiest society in the world.

6. Health for our society depends upon disengagement from and relinquishment of that script of military consumerism. This is a disengagement and relinquishment that we mostly resist and about which we are profoundly ambiguous.

7. It is the task of ministry to de-script that script among us. That is, to enable persons to relinquish a world that no longer exists and indeed never did exist.

8. The task of descripting, relinquishment and disengagement is accomplished by a steady, patient, intentional articulation of an alternative script that we say can make us happy and make us safe.

9. The alternative script is rooted in the Bible and is enacted through the tradition of the Church. It is an offer of a counter-narrative, counter to the script of technological, therapeutic, consumer militarism.

10. That alternative script has as its most distinctive feature – its key character – the God of the Bible whom we name as Father, Son, and Spirit.

11. That script is not monolithic, one dimensional or seamless. It is ragged and disjunctive and incoherent. Partly it is ragged and disjunctive and incoherent because it has been crafted over time by many committees. But it is also ragged and disjunctive and incoherent because the key character is illusive and irascible in freedom and in sovereignty and in hiddenness, and, I’m embarrassed to say, in violence – [a] huge problem for us.

12. The ragged, disjunctive, and incoherent quality of the counter-script to which we testify cannot be smoothed or made seamless because when we do that the script gets flattened and domesticated and it becomes a weak echo of the dominant script of technological, consumer militarism. Whereas the dominant script of technological, consumer militarism is all about certitude, privilege, and entitlement this counter-script is not about certitude, privilege, and entitlement. Thus care must be taken to let this script be what it is, which entails letting God be God’s irascible self.

13. The ragged, disjunctive character of the counter-script to which we testify invites its adherents to quarrel among themselves – liberals and conservatives – in ways that detract from the main claims of the script and so to debilitate the focus of the script.

14. The entry point into the counter-script is baptism. Whereby we say in the old liturgies, “do you renounce the dominant script?”

15. The nurture, formation, and socialisation into the counter-script with this illusive, irascible character is the work of ministry. We do that work of nurture, formation, and socialisation by the practices of preaching, liturgy, education, social action, spirituality, and neighbouring of all kinds.

16. Most of us are ambiguous about the script; those with whom we minister and I dare say, those of us who minister. Most of us are not at the deepest places wanting to choose between the dominant script and the counter-script. Most of us in the deep places are vacillating and mumbling in ambivalence.

17. This ambivalence between scripts is precisely the primary venue for the Spirit, so that ministry is to name and enhance the ambivalence that liberals and conservatives have in common that puts people in crisis and consequently that invokes resistance and hostility.

18. Ministry is to manage that ambivalence that is crucially present among liberals and conservatives in generative faithful ways in order to permit relinquishment of [the] old script and embrace of the new script.

19. The work of ministry is crucial and pivotal and indispensable in our society precisely because there is no one except the church and the synagogue to name and evoke the ambivalence and to manage a way through it. I think often I see the mundane day-to-day stuff ministers have to do and I think, my God, what would happen if you took all the ministers out. The role of ministry then is as urgent as it is wondrous and difficult.

[These theses were presented at the Emergent Theological Conversation, September 13-15, 2004, All Souls Fellowship, Decatur, GA., USA]

Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part VIII, On Abortion

‘The Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade meant that country girls like Leeta or Teri or others like them, who found themselves “in trouble,” would have the option of privatizing their problem by removing the stigma of an unwanted pregnancy from the eyes of the congregation. It wouldn’t be necessary for the community to promise to help raise the child. The church would not have the opportunity to offer the hospitality of Jesus to a scared teenager and her family. Nor would it have a chance to fail to do so, as it had sometimes done in the past. No one would know. It was none of the community’s business’. – Richard Lischer, Open Secrets: A Memoir of Faith and Discovery, 208–9.

‘The Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade meant that country girls like Leeta or Teri or others like them, who found themselves “in trouble,” would have the option of privatizing their problem by removing the stigma of an unwanted pregnancy from the eyes of the congregation. It wouldn’t be necessary for the community to promise to help raise the child. The church would not have the opportunity to offer the hospitality of Jesus to a scared teenager and her family. Nor would it have a chance to fail to do so, as it had sometimes done in the past. No one would know. It was none of the community’s business’. – Richard Lischer, Open Secrets: A Memoir of Faith and Discovery, 208–9.

Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets: Part VII, On the Church Calendar

‘The Protestant church was already in the process of discarding the named Sundays of Lent and Easter even as we blessed and planted the seeds. Now they bear the evocative names “The First Sunday in Lent,” “the Second Sunday in Lent,” and so on. The fourth Sunday in Lent was once named Laetare, which means “rejoice.” It was known in the church as Refreshment Sunday. On this Sunday rose paraments replaced the traditional purple of Lent, and, psychologically and spiritually, we breathed a little easier. The color rose seemed to say, There’s light at the end of the tunnel. Even at the dead center of Lent, Christ is risen.