Let the words of my mouth and the meditations of my heart be acceptable in Thy sight, O Lord, my strength and my Redeemer.

The parable of the Good Samaritan is more complex than it might seem at a first or a hundredth reading. Its central point is precious and also clear, that we are to help where help is needed, putting aside every distinction and consideration that might give us an excuse to pass by on the other side. If we are more like the scribe and the priest on too many occasions, sometimes we encounter, and sometimes we are, good Samaritans, people who do the kind and necessary thing, even the difficult and costly thing, when occasion arises, hoping nothing in return but to secure the well being of a stranger. This nameless, and fictional, Samaritan has left innumerable descendants, and they have been a blessing to us all.

Luke gives the parable an interesting context. A lawyer rises to “test” Jesus. He asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. Jesus asks him what is written in the law. He answers, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus replies, “Do this and you will live.” Good brothers and sisters in Christ, let us ponder the fact that, if Jesus is to be believed, the law of Moses is fully sufficient to the securing of eternal life.

The lawyer is offering an established first-century Jewish understanding of the essence of the law of Moses. Notice that here the lawyer cites the law. In the Gospel of Matthew it is Jesus who quotes it. He does so repeatedly, a fact which might explain, though it cannot excuse, the belief widely held among Christians that the commandment originated with Jesus. I have even seen it argued that this commandment to love, which is found in Leviticus, a Book of Moses, epitomizes the difference between the law of Moses and the law of Christ, between Judaism and Christianity. It’s hard to know sometimes whether to laugh or to weep or to tear one’s hair. Be that as it may. Here Luke gives us two first-century Jews discussing the correct interpretation of a particularly venerated law of Moses.

What is called a “law” here is in fact a phrase taken from a law, Leviticus 19:18, which forbids grudgeholding and revenge. In the New Testament the phrase is consistently understood to have a much broader meaning than its original context would give it. Indeed, it seems to be in its nature somehow to have and to acquire always broader reference. The phrase occurs three times in the Gospel of Matthew. In the first, Jesus enlarges the circle of those to be loved to include one’s enemy, since God “makes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sendeth rain on the just and the unjust.” Again, when a young man asks what he must do to be saved, Jesus cites the Ten Commandments, and then, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” It is remarkable to find this phrase, stripped of its context, given equal standing with the Decalogue. Its great importance is made clear again when Jesus responds to a question put to him by another lawyer – “Teacher, which is the great commandment in the law?” Jesus replies, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all they heart, and with all the soul, and with all thy mind. This is the great and first Commandment. And a second like unto it is this, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments the whole law hangeth, and the prophets.” In the Gospel of Mark Jesus quotes the great commandment, to love the Lord, as the first in importance. Then he says, “The second is this, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself, There is none other commandment greater than these.” Paul quotes the phrase in Romans, saying that the law is summed up “in this word, namely, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” He says, “Love worketh no ill to his neighbor; therefore love is the fulfillment of the law.”

In the exchange in Matthew that prompts the famous parable of compassion in today’s text, the lawyer who is testing Jesus grants the authority of this commandment, but, being a lawyer, he wants a clarification. “Who is my neighbor?” Luke says he is seeking to justify himself when he asks this question, which might be understood to mean that he is asking “Whom am I obliged to love? and, conversely, who falls outside the range of those to whom love is owed?” Presumably the lawyer in his attempt to be obedient to this law has been proceeding on a definition of his own that allows him to be a little bit selective. The Hebrew word translated “neighbor” can mean kinsman, friend, companion, or neighbor as we understand the word. The Greek word suggests less in terms of personal relationship and more in terms of nearness, physical proximity. In both cases, the concept “neighbor” is potentially somewhat narrow, as it is for us. The lawyer, intent on his own salvation, clearly does not want on one hand to risk loving where he would realize no eternal benefit from it, or, on the other. to allow himself indifference or hostility toward anyone on whom his eternal happiness might depend. In the way of pious people in all times and places, he wants to get it right.

Now, as it happens, there is another law, another commandment to love, in the same chapter of Leviticus, fifteen verses on, which is far too little known, though we must assume Jesus knew it, and probably the lawyer did, too. It says: When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God. A phrase very like the one with which we are familiar could have floated free of this context – Thou shalt love the alien as thyself. Here the law specifically draws the stranger, as stranger, into the great defining narrative of the people Israel. Aliens are in effect naturalized, made, in the same language, properly the objects of love just as neighbors are, and on precisely the grounds that they are outsiders. Without reference to origins or any other quality, their circumstance is all the identity that matters. Put these laws side by side, and together they make neighbor and stranger equivalent terms. In the language of the Hebrew Bible there is a structure called a merism. The naming of two extremes – heaven and earth, good and evil – implies everything that falls between them. This is to say that, taken together, the commandments to love in Leviticus are very broad indeed. Whence, perhaps, the energy that makes this fragment of a law, thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself, rank among the greatest laws.

Still, the lawyer seems to feel that he can love where the law requires, that the requirement of the law can be limited and defined – and that self-interest can inspire a good enough approximation to that exalted emotion to satisfy the commandment, and to serve his eternal purposes. Looking at context again, this characteristic pairing of the laws to love God and neighbor makes them both dependent on the one word “love.” Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, and thy neighbor as thyself. To perform actions that only signify love of God is not sufficient – is in fact reprehensible, offensive to God, as all the prophets tell us. The very emphatic language of the first of the laws – love is to engross heart, soul, strength and mind – makes this point. It is in effect a definition of love, that it is engrossed by its object, and is in that sense selfless. The lawyer is using his own interests, piously defined, to determine the limits of his love as well as its proper focus. Insofar as his thinking influences his feeling, he is preventing himself from really loving anyone. The self-forgetfulness love requires is impossible for him.

Still, the lawyer seems to feel that he can love where the law requires, that the requirement of the law can be limited and defined – and that self-interest can inspire a good enough approximation to that exalted emotion to satisfy the commandment, and to serve his eternal purposes. Looking at context again, this characteristic pairing of the laws to love God and neighbor makes them both dependent on the one word “love.” Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, and thy neighbor as thyself. To perform actions that only signify love of God is not sufficient – is in fact reprehensible, offensive to God, as all the prophets tell us. The very emphatic language of the first of the laws – love is to engross heart, soul, strength and mind – makes this point. It is in effect a definition of love, that it is engrossed by its object, and is in that sense selfless. The lawyer is using his own interests, piously defined, to determine the limits of his love as well as its proper focus. Insofar as his thinking influences his feeling, he is preventing himself from really loving anyone. The self-forgetfulness love requires is impossible for him.

I propose that the parable turns on this point. The kindness of the Samaritan has no self-interest behind it, no motive of friendship or kinship. In fact, there was inveterate hostility between Samaritans and Jews. In a broad, cultural sense, the Jew was the Samaritan’s enemy. Freud might have referred this hostility to what he called the narcissism of minor difference, the tendency of friction and conflict to occur most frequently between populations that are most similar to each other. Our own United States has engaged in three wars in which its national survival was at stake – the Revolution and the War of 1812, fought against England, and the Civil War, between our own North and South. Over the centuries Europeans have found differences among themselves that were intolerable to them and trivial or invisible to outsiders. And so with the world at large.

The kingdom of Israel became divided after the reign of Solomon. After the separation, the northern kingdom was called Israel, then Samaria, and the southern kingdom was called Judah, then Judea. This distinction is reflected in the word “Jew,” which means Judean. Both peoples centered their faith and worship around the five books of Moses. The Samaritans did not accept the prophets or worship at the temple in Jerusalem but at a temple of their own in Bethel. These distinctions are reflected in the Old Testament text from the writing of the prophet Amos. Christianity, of course, has its origins in the religious culture of Judea, which might lead to further, sadder reflection on the narcissism of minor differences. In any case, the antipathy felt on both sides, Samaritan and Judean, was very real and is certainly a factor in this parable. The compassion of the Samaritan expresses an utter freedom, on this occasion, at least, from the mean distinctions culture and history seem always to generate and to impose. In making the good man of the parable a Samaritan, another inheritor of the traditions of Moses, and specifically of the commandments to love in Leviticus, Jesus suggests that this “heretic’s” understanding of them and obedience to them were of a higher order than the lawyer’s, a man who had devoted himself to mastering the law, and probably prided himself on his command of it. Jesus is inviting his hearers to put aside these same mean distinctions, to emulate a Samaritan. In putting aside the strictures of religion, they will enable themselves to be truly obedient to the law. We are all painfully aware that the most telling indictment of Christianity is our persistent failure to distinguish identity and adherence from actual, lived faithfulness.

But Jesus broadens the question much further. A commandment to love is mysterious in itself. Thou shalt love the Lord thy God. How is this done? If one’s heart does not incline to love, or to this kind of love, what then? How does one love God, of Whom reverence itself requires us to acknowledge that we can know so little? Jesus says; the commandment “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself” is like unto the first great law. How is this to be understood? For Christians, the answer lies in Jesus Himself, in the Incarnation. In another famous parable, this one in the 25th chapter of Matthew, the Son of Man, appearing enthroned as apocalyptic judge of all the nations of the earth, says to the blessed, “I was hungry, and you fed me. I was naked and you clothed me.” To the Samaritan he would say, “I was beaten and robbed and left lying by the road, and you bound my wounds and cared for me, bearing every expense of time and effort and money, expecting nothing in return.” This parable in Matthew is also addressed to the question put by the lawyer in the text we have read today, what one must do to inherit eternal life, and there is absolutely nothing sectarian in the answer it gives. Humanity’s remotest ancestors could come under its blessing. The impulse to be kind manifest in the parable of the Good Samaritan is a human impulse, rarer than it ought to be and beautiful wherever it finds expression. Christians can know that they honor God Himself whenever they honor another human being, showing that they understand the value of his or her dignity, life, peace and safety. Jesus, man of sorrows, Son of Man, gives us most explicit instruction on this point. If we fail in our reverence toward others, it is not because we don’t know better.

Still there is a question. Can we oblige God to think well of us by showing mercy and generosity? As children of the Reformation we must answer, no, we cannot. The revelation we are given in Matthew’s parable of the Great Judgment is not simply that heaven blesses acts of mercy, but something vastly more astounding, that Christ is present in those who are vulnerable to our oppression or neglect, and that Christ feels and remembers in his own person every kindness that is done to them. It is not the pathos of the world but its profound sacredness that is shown to us. At issue in our parable is not how the word neighbor is to be understood, but what is meant by the word love.

That one verb expresses the right relation of ourselves to God and of ourselves to whomever circumstance puts in our way. Notice how Jesus’s parable shifts our perspective. The neighbor is definitely not a relative, not the member of the community, not a co-religionist. Jesus’s having made his protagonist a Samaritan suggests that he takes the lawyer to expect the definition of the word “neighbor” to fall within one of these categories, if not more than one. The letter of the law could be used, as it so often is, to deny the spirit of the law. Jesus does not even allow the word to mean “whoever needs our kindness or our help,” though this would be a very broad definition, since everyone does need kindness very often. Instead he defines the neighbor not as the proper object of love – but as the one who acts lovingly. More precisely, his story moves the lawyer to this recognition. If love of neighbor were a commandment honored generally, then its effects would be reciprocal. As neighbors we would receive the benefits of this love, and also extend them to others. We create ourselves as neighbors – and fulfill the law – when we honor our side of this shared bond, whether the bond is acknowledged on the other side or not. The word has as broad a definition as we have insight, engagement and compassion to give it.

And there is always another, much larger, context. The Gospel gives us a scene in which a legal scholar is disputing with a self-taught carpenter about a point of law. A bright fellow, he must have thought, interesting enough to spar with a little. He’s attracting crowds, and that can be dangerous. If I give him a question we specialists have struggled with, I might take him down a peg. No harm in that.

The writers of the Gospels take this carpenter to have been, in fact, the epitome of holiness, the Word made flesh, the universal judge. The lawyer is debating the law with God Himself, whose own commandments are at issue. This makes the scene most remarkable. But it is remarkable for nothing more than for the fact that Jesus, the Christ of Luke’s Gospel, is an ordinary man. On a landscape where prophets have appeared he is taken by some people to be one more prophet. Others have no opinion, or take no notice. But, in light of the utterly singular Presence the writer we call Luke understood him to be, there is the greatest significance in the fact that he really is one of us. He might have been the man lying injured by the side of the road, and he might have been the Samaritan who took him up. His wounds would have bled, his voice and his hands would have comforted, just as theirs did, just as ours do. The deep holiness with which human life is invested, which is so great that the Christ could take on true humanity without the least diminishment of his holiness, should tell us who we are and whom we are among, and why it is that the love of neighbor is “like unto” the love of God.

Let us be truly faithful to the last commandment of Jesus, that we love one another. Amen.

♦

Marilynne Robinson preached this sermon at the Congregational United Church of Christ of Iowa City, 14 July 2013.

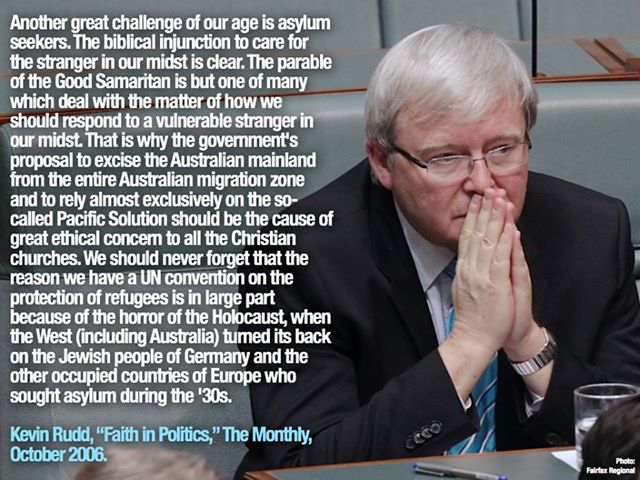

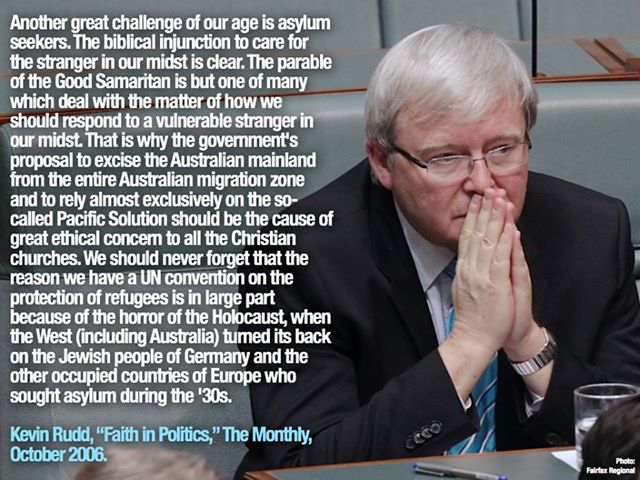

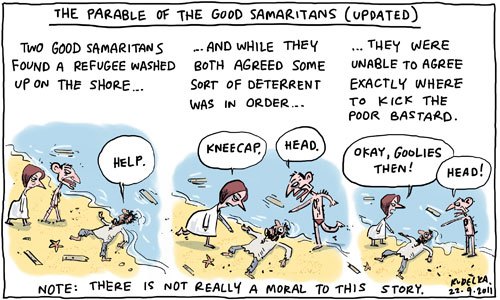

[A note on the first image: The first image, of Kevin Rudd, is accompanied with words from Rudd’s essay ‘Faith in Politics’, published in The Monthly, October 2006. It seemed a fitting image to use given the subject of the sermon, and the shameful political context in Australia during recent days from where I first read it.]

The thought of my affliction and my homelessness is wormwood and gall! My soul continually thinks of it and is bowed down within me. But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope: The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness. “The Lord is my portion,” says my soul, “therefore I will hope in him.” – Lamentations 3.19–24

The thought of my affliction and my homelessness is wormwood and gall! My soul continually thinks of it and is bowed down within me. But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope: The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness. “The Lord is my portion,” says my soul, “therefore I will hope in him.” – Lamentations 3.19–24