Václav Havel is no stranger to this blog. I find myself turning again and again to his words – words matured in the crucible of suffering and of hope, in the illusive corridors of ‘power’ and in the freedom of ‘powerlessness’. Recently, I had reason to revisit reading a number of his talks given during the ’90s. It was challenging to re-hear these words from his famous Commencement Address given at Harvard University on 8 June 1995:

Václav Havel is no stranger to this blog. I find myself turning again and again to his words – words matured in the crucible of suffering and of hope, in the illusive corridors of ‘power’ and in the freedom of ‘powerlessness’. Recently, I had reason to revisit reading a number of his talks given during the ’90s. It was challenging to re-hear these words from his famous Commencement Address given at Harvard University on 8 June 1995:

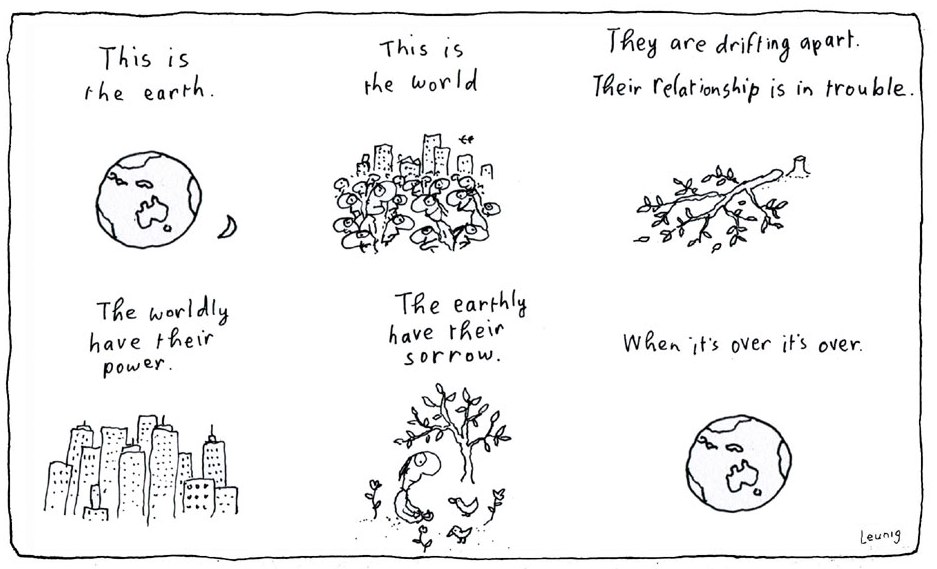

The veneer of global civilization that envelops the modern world and the consciousness of humanity, as we all know, has a dual nature, bringing into question, at every step of the way, the very values it is based upon, or which it propagates. The thousands of marvellous achievements of this civilization that work for us so well and enrich us can equally impoverish, diminish, and destroy our lives, and frequently do. Instead of serving people, many of these creations enslave them. Instead of helping people to develop their identities, they take them away. Almost every invention or discovery from the splitting of the atom and the discovery of DNA to television and the computer can be turned against us and used to our detriment. How much easier it is today than it was during the First World War to destroy an entire metropolis in a single air-raid. And how much easier would it be today, in the era of television, for a madman like Hitler or Stalin to pervert the spirit of a whole nation. When have people ever had the power we now possess to alter the climate of the planet or deplete its mineral resources or the wealth of its fauna and flora in the space of a few short decades? And how much more destructive potential do terrorists have at their disposal today than at the beginning of this century.

In our era, it would seem that one part of the human brain, the rational part which has made all these morally neutral discoveries, has undergone exceptional development, while the other part, which should be alert to ensure that these discoveries really serve humanity and will not destroy it, has lagged behind catastrophically.

Yes, regardless of where I begin my thinking about the problems facing our civilization, I always return to the theme of human responsibility, which seems incapable of keeping pace with civilization and preventing it from turning against the human race. It’s as though the world has simply become too much for us to deal with.

There is no way back. Only a dreamer can believe that the solution lies in curtailing the progress of civilization in some way or other. The main task in the coming era is something else: a radical renewal of our sense of responsibility. Our conscience must catch up to our reason, otherwise we are lost.

It is my profound belief that there is only one way to achieve this: we must divest ourselves of our egoistical anthropocentrism, our habit of seeing ourselves as masters of the universe who can do whatever occurs to us. We must discover a new respect for what transcends us: for the universe, for the earth, for nature, for life, and for reality. Our respect for other people, for other nations, and for other cultures, can only grow from a humble respect for the cosmic order and from an awareness that we are a part of it, that we share in it and that nothing of what we do is lost, but rather becomes part of the eternal memory of Being, where it is judged.

A better alternative for the future of humanity, therefore, clearly lies in imbuing our civilization with a spiritual dimension. It’s not just a matter of understanding its multicultural nature and finding inspiration for the creation of a new world order in the common roots of all cultures. It is also essential that the Euro-American cultural sphere the one which created this civilization and taught humanity its destructive pride now return to its own spiritual roots and become an example to the rest of the world in the search for a new humility.

General observations of this type are certainly not difficult to make, nor are they new or revolutionary. Modern people are masters at describing the crises and the misery of the world which we shape, and for which we are responsible. We are much less adept at putting things right.

So what specifically is to be done?

I do not believe in some universal key or panacea. I am not an advocate of what Karl Popper called “holistic social engineering”, particularly because I had to live most of my adult life in circumstances that resulted from an attempt to create a holistic Marxist utopia. I know more than enough, therefore, about efforts of this kind.

This does not relieve me, however, of the responsibility to think of ways to make the world better.

It will certainly not be easy to awaken in people a new sense of responsibility for the world, an ability to conduct themselves as if they were to live on this earth forever, and to be held answerable for its condition one day. Who knows how many horrific cataclysms humanity may have to go through before such a sense of responsibility is generally accepted. But this does not mean that those who wish to work for it cannot begin at once. It is a great task for teachers, educators, intellectuals, the clergy, artists, entrepreneurs, journalists, people active in all forms of public life.

Above all it is a task for politicians.

Even in the most democratic of conditions, politicians have immense influence, perhaps more than they themselves realize. This influence does not lie in their actual mandates, which in any case are considerably limited. It lies in something else: in the spontaneous impact their charisma has on the public.

The main task of the present generation of politicians is not, I think, to ingratiate themselves with the public through the decisions they take or their smiles on television. It is not to go on winning elections and ensuring themselves a place in the sun till the end of their days. Their role is something quite different: to assume their share of responsibility for the long-range prospects of our world and thus to set an example for the public in whose sight they work. Their responsibility is to think ahead boldly, not to fear the disfavour of the crowd, to imbue their actions with a spiritual dimension (which of course is not the same thing as ostentatious attendance at religious services), to explain again and again both to the public and to their colleagues that politics must do far more than reflect the interests of particular groups or lobbies. After all, politics is a matter of serving the community, which means that it is morality in practice. And how better to serve the community and practise morality than by seeking in the midst of the global (and globally threatened) civilization their own global political responsibility: that is, their responsibility for the very survival of the human race?

Last night’s edition of the ABC program Sunday Nights, hosted by John Cleary, included an interview with the Rev Dr Kerry Enright, the outgoing National Director of UnitingWorld, and a friend of mine. During the interview, Kerry reflects upon two of his favorite topics – the catholic nature of the church as gift from God and as sign to the world, and on the role of the church in civil society (here the discussion is focused particularly on Fiji, Australia and New Zealand). He also talks a bit about his forthcoming appointment as minister of Knox Church (Presbyterian) in Dunedin. I’m looking forward to welcoming Kerry back to Dunedin, and back to the PCANZ, soon. You can listen to the interview here.

Last night’s edition of the ABC program Sunday Nights, hosted by John Cleary, included an interview with the Rev Dr Kerry Enright, the outgoing National Director of UnitingWorld, and a friend of mine. During the interview, Kerry reflects upon two of his favorite topics – the catholic nature of the church as gift from God and as sign to the world, and on the role of the church in civil society (here the discussion is focused particularly on Fiji, Australia and New Zealand). He also talks a bit about his forthcoming appointment as minister of Knox Church (Presbyterian) in Dunedin. I’m looking forward to welcoming Kerry back to Dunedin, and back to the PCANZ, soon. You can listen to the interview here.