Month: November 2013

black friday

lots of

tweets

this morning

about BLACK FRIDAY.

never heard of it

’til

this year.

what

a

bizarre

project

for people

(of all things)

to have.

i might

this day

make cheese

instead.

advent: two poems

When I see the cradle rocking

What is it that I see?

I see a rood on the hilltop

Of Calvary.

When I hear the cattle lowing

What is it that they say?

They say that shadows feasted

At Tenebrae.

When I know that the grave is empty,

Absence eviscerates me,

And I dwell in a cavernous, constant

Horror vacui.

– Donald Hall, ‘Advent’, in The Back Chamber: Poems (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 22.

◊

‘A Praise in Advent’, by Arnold Kenseth

‘A Praise in Advent’, by Arnold Kenseth

See, as we stumble in the Advent snows,

God comes to fathom us. He sends his Son,

A gentleness by whom our fear’s undone,

A jubilance who overcomes our woes.

At first, we hold him in the ancient picture:

Skoaled by great angels, crooned by watching beasts,

Thick-footed shepherds by his side, deep frosts;

Love’s history: for you and me hope’s texture.

Now he is with us, at our village stones,

Fingering the mortar, testing. His mirth

Assaults our streets, and daily he goes forth

Troubling our elegant houses with unknowns

That were and are before whatever is

Began to be. By him was made the air,

Sparrows, eagles, Asias, the sweet despair

Of the free mind. All honest things are his.

He is the holy one we waited for, the Word

Who speaks to us who stammer back, the plot

Against the rich and poor, the Gordian knot

Our wit cannot untie. He is time’s Lord.

Thus, shall we sing him well these Christmas days

And at his birth-feast practice with him praise.

– Arnold Kenseth, ‘A Praise in Advent’, in The Ritual Year: Christmas, Winter, and Other Seasons: Poems (Amherst: Amherst Writers and Artists Press, 1993), 90.

More Advent Resources

This year, the Centre for Theology and Ministry has produced a resource to ‘assist individuals, households and small groups in their journey through Advent’. The booklet, which combines ‘individual daily reflections comprising a suggested Scripture reading, some words of reflection and a short prayer’, plus ‘ideas that can be used in the household or multi-age contexts’, can be downloaded here.

This year, the Centre for Theology and Ministry has produced a resource to ‘assist individuals, households and small groups in their journey through Advent’. The booklet, which combines ‘individual daily reflections comprising a suggested Scripture reading, some words of reflection and a short prayer’, plus ‘ideas that can be used in the household or multi-age contexts’, can be downloaded here.

Also, a few years back, I posted some advent reflections. These can be accessed via here, here, here and here.

Advent Reflections: 2011–12

- ‘The Incarnate One’, by Edwin Muir

- Looking for God – a short reflection

- ‘Virgin’

- An Advent Prayer by a 5-year-old

- Marilyn Chandler McEntyre, ‘Simeon with the Christ Child in the Temple’

- ‘The Coming’

- On Max Ernst’s ‘The Virgin Chastises the infant Jesus before Three Witnesses: André Breton, Paul Éluard, and the Painter’ (1926)

- ‘Advent Stanzas’ by Robert Cording

- Advent as learning something of God’s own simultaneous ‘Yes’ and ‘No’

- ‘A Reflection on Advent’, by Rowan Williams

- Setting Out into the Dark with God: A Christmas Meditation

You can also access previous year’s reflections here: 2007, 2009 and 2010.

On dangerous ideas to change the world

A recent episode of Q&A, filmed during the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, dispensed with the most-usual band of dull politicians and instead hosted Peter Hitchens and Germaine Greer (a regular guest on the show), as well as two lesser minds – Hanna Rosin and Dan Savage. (Incidentally, I’ve never seen Tony Jones, who normally does a stellar job, moderate the discussion as poorly as he did. An off night for Tony.) As each guest responded to questions on subjects as diverse as the collapse of Western civilization, internet hook ups, women’s liberation, conservative politics and the permanence (or otherwise) of marriage in the ‘modern’ world, it became startlingly obvious that not only was Hitchens by far the best student of history on the panel but that he was also the only one who seems to hae a scoobie about the moral realities that give shape to such.

The final question, which came from Lisa Malouf, in more ways than one elicited the most revealing responses. The question was: ‘Which so-called dangerous idea do you each think would have the greatest potential to change the world for the better if were implemented?’

Here are the responses:

The entire episode, which is worth watching, can be downloaded here.

Poems of Devotion. A Review

Luke Hankins (ed.). Poems of Devotion: An Anthology of Recent Poets (Eugene, OR.: Wipf and Stock, 2012). 236pp; ISBN: 978-1-61097-712-8

Luke Hankins (ed.). Poems of Devotion: An Anthology of Recent Poets (Eugene, OR.: Wipf and Stock, 2012). 236pp; ISBN: 978-1-61097-712-8

A guest-review by Mike Crowl.

Luke Hankins is not quite thirty. He’s already published a highly regarded book of poems, Weak Devotions, in which he ‘wrestles with the issues Donne, Herbert, Hopkins … also found worthy of their most impassioned work’ (John Wood), and a chapbook of translations from the French poems of Stella Vinitchi Radulescu (three of her poems are included in this book). He is also senior editor of the Asheville Poetry Review.

In Poems of Devotion, Hankins is aiming to present to the modern reader a substantial collection of poems on the theme of devotion, from a wide range of poets – American, English, and other nationalities, including some translations. If the word ‘devotion’ arouses thoughts of prissy, sappy pseudo poems that barely scratch the surface, you will find Hankins’ collection eschews such works; much of what is here is tough, painful, meditative, worshipful, and certainly deep enough to call you back again and again.

Hankins presents poets who are willing to wrestle with God. Many of them come from angles that are anything but devotional in the generally accepted sense. Some know from the outset where they’re going, but Hankins has looked more for poets who appear to work out their experience as they go along. As he writes in his introduction: ‘Great poems are – if not invariably, at least most often – an unfolding, not only for the reader, but for the poet in the process of composing’. And he quotes fellow poet, Charles Wright: ‘Writing is listening. Religious experience is silent listening and waiting. I have always been able to tell whether something I am writing is genuinely an expression of revelation or if it’s just me exercising my intellect. I can feel the difference, see it and taste it, but I don’t know how I can do that’. In the poems collected here, poetry is for the most part a means of meditating rather than an experience recounted.

That is not to say that these are floppy works without poetic structures: subtle rhymes and rhythms abound, the last lines are often a revelation; sharp metaphors of atmosphere and the spirit and creation are evident on every hand. The poets have taken their original searchings and crafted them well.

Many of these poets are not ‘saints’ in any ordinary sense, though they bring themselves to understand the need to submit to God’s will, even when it seems at odds with their very being, or when they haven’t found the answer they set out to look for. Old poets still look for answers in their old age. (Leonard Cohen has a couple of very good prose poems, for instance). There is also great joy and wonder (for example, in Luci Shaw’s Mary’s Delight; Shaw isn’t a poet I’ve greatly admired in the past, but this is a beauty) and praise (several poems are modern psalms) and worship (Thomas Merton’s Evening: Zero Weather, for instance).

Then there are the strange poems: Amit Majmudar’s extraordinary long piece about the angel we generally know as Satan; Michael Schiavo’s odd ‘dub versions of Shakespeare’s sonnets’, Bruce Beasley’s long, collage-like ‘Damaged Self-Portrait’.

Hankins offers seventy-seven poets in all. Some have only one poem, some have several, some provide several parts of a larger poem. But there’s no sense of stinting on the poets here; each one has room to breathe. There are some familiar names – T.S. Eliot, Theodore Roetke, E.E. Cummings, R.S. Thomas, Denise Levertov, Richard Wilbur – but the majority are unfamiliar – to me, anyway, and I suspect to many readers of the book.

The poems are book-ended by the substantial introduction, and a reprint of an interview between Hankins and Justin Bigos, which gives some background to Hankins and his poetic stance.

Launching

Last night, the Knox Centre hosted the launch of four books:

Last night, the Knox Centre hosted the launch of four books:

- The Church in Post-Sixties New Zealand: decline, growth and change, and Losing Our Religion? Changing Patterns of Believing and Belonging in Secular Western Societies, both by my colleague Kevin Ward. And,

- Descending on Humanity and Intervening in History: Notes from the Pulpit Ministry of P.T. Forsyth, and Hallowed be Thy Name: The Sanctification of All Things in the Soteriology of P.T. Forsyth, by yours truly.

John Stenhouse and John Roxborogh spoke to Kevin’s books, and Mike Crowl and Murray Rae spoke to mine. All did a super job. It was a great night. Post-launch, the two authors (and a few others) then partied on with Chinese food and whiskey. The gastronomical combo seemed to work well.

Mike has since posted what he really would have liked to have said, some reflections on his experience of reading P T Forsyth.

Those unable to make it along to the launch can still pick up a copy of the books at the special book launch price. If you’re interested, please contact either Kevin or myself.

‘Our Great High Priest’, a song by Glen Soderholm

Glen Soderholm is an accomplished musician and songwriter, an ordained minister (with the Presbyterian Church in Canada), and a teacher in the area of the theology and curating of worship. He tells me that he is also ‘currently part of a group of friends giving birth to a missional community in his living room and neighbourhood, and that he has a deep and abiding interest in the relationship of trinitarian/incarnational/onto-relational theology to worship, arts, and culture’.

Glen Soderholm is an accomplished musician and songwriter, an ordained minister (with the Presbyterian Church in Canada), and a teacher in the area of the theology and curating of worship. He tells me that he is also ‘currently part of a group of friends giving birth to a missional community in his living room and neighbourhood, and that he has a deep and abiding interest in the relationship of trinitarian/incarnational/onto-relational theology to worship, arts, and culture’.

Following my recent post on James Torrance’s hymn, ‘I know not how to pray, O Lord’, Glen contacted me and shared with me his own song on that theme, ‘Our Great High Priest’. This song, he tells me, was ‘inspired by a life-changing encounter with James Torrance’s book Worship, Community, and the Triune God of Grace. I read it and felt like I’d come home’. Glen gave me permission to share his wonderful song.

Our great high priest now at the throne

You ever live to pray for your own

And to the Father, you make us known

Our great high priest now at the throne

We long to pray, but we don’t know how

We yearn to stay, but lack the power

Our wills are weak, our tongues are tied

Oh lift us now, right to your side

For us you came to this low plane

For us you lived with joy and pain

For us you died to set us free

And rose on high to bear our plea

‘Iolaire’, by Donald S. Murray

Donald Murray, who is originally from Lewis but now lives in Shetland, has shared a very moving (and very Calvinist!) poem about the Iolaire Disaster in 1919 for Remembrance Day 2013:

Sometimes we still sit upon that ledge

and consider the dark fervour of the waves,

wondering why some of us went under

while others clung with every fibre and were saved.

There are no answers to that question. Fortune

(whatever scholars tell us) does not favour the brave

or the virtuous. It rescued some

who could be wicked, hard and wretched ones enslaved

to drink or women, and swept aside

the good, the kind, those who each day forgave

others. We only know a rope was hurled

and we possessed both grip and faith

strong enough to hold it. Nothing else is known to us,

all as dark, intangible as the fervour of these waves.

Ministry and theology for a ‘Post-Fukushima world’

The Rev. Dr. Naoya Kawakami is the Secretary General of Touhoku HELP, a highly commendable ministry birthed in the wake of the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011. Touhoku HELP produced a video for a presentation at the recent WCC General Assembly in Busan. With Korean narration and English subtitles, it illustrates not only the recent (note: some of the footage was filmed last August) situation in Fukushima but also something of the inspiring ministry that is emerging from the rubble.

Naoya and I maintain a steady and prayerful correspondence. In a recent exchange, he wrote of the overwhelming number – over a half of million! – who live with the effects of radiation. He also wrote of his own need, amidst the crushing wave of need around him, to ‘keep time to think and read’, and of the urgency for what he calls a ‘new theology for this “Post-Fukushima” world’.

He mentioned too about a recent meeting of Japanese and Korean theologians who conversed about the situation birthed by the Fukushima tragedy. Among the topics discussed was the possibility of post-mortem salvation for the many victims of the tsunami and of radiation poisoning. He said,

He mentioned too about a recent meeting of Japanese and Korean theologians who conversed about the situation birthed by the Fukushima tragedy. Among the topics discussed was the possibility of post-mortem salvation for the many victims of the tsunami and of radiation poisoning. He said,

In the tradition of the major protestant churches, there is no way of salvation for the dead who have not believed in Jesus Christ as Lord during their living time. But many Japanese theologians who have read PT Forsyth have spoken out against this tradition since the triple disaster. Yesterday, we talked about this issue. I shared the logic of Forsyth for this issue from his book This Life and the Next.

Inspired by Forsyth’s lively challenge (via his Protestant reappraisal of the doctrine of purgatory) that God alone – and not death – determines the time when creation reaches its maturity, these theologians found themselves, in faith and together, straining to hear – but hearing indeed – the promise of the Lord of hope in a land crushed under the burden of fear and despair.

Please join me in praying for Naoya (he carries a great burden for the people who live in the Fukushima area, and for the gospel), and please consider supporting the work of Touhoku HELP.

[Naoya’s dissertation was on Japanese receptions of Forsyth’s theology, and the subject of post-mortem conversion receives attention in the final chapter of my own study, Hallowed be Thy Name: The Sanctification of All Things in the Soteriology of P.T. Forsyth. Naoya kindly described my latest offering on Forsyth, Descending on Humanity and Intervening in History, as a ‘big present for Fukushima’.]

In defence of Clive James’ translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy

I’ve started reading Clive James’ translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, a volume which has been met with mixed reception. Colin Burrow (LRB) and Ian Thomson (FT), among others, have signalled their being largely unimpressed with James’ efforts. A common charge is that the translation lacks fidelity to the original in which ‘accuracy, precision and concision were sovereign virtues’. It’s not only ‘short on precision’, however. It also has too many ‘slangy phrases’ which betray the voice of the antipodean translator as much as they do the original author.

I’ve started reading Clive James’ translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, a volume which has been met with mixed reception. Colin Burrow (LRB) and Ian Thomson (FT), among others, have signalled their being largely unimpressed with James’ efforts. A common charge is that the translation lacks fidelity to the original in which ‘accuracy, precision and concision were sovereign virtues’. It’s not only ‘short on precision’, however. It also has too many ‘slangy phrases’ which betray the voice of the antipodean translator as much as they do the original author.

I’m still in ‘Hell’, so I ought to reserve my comments – and reserve the right to change my mind – but apparent already to me is that while James has taken certain liberties, made certain ‘additions’ (his is almost a paraphrase in parts), the wood is certainly not lost for the trees, and the result is something fresh, energetic, poetically sophisticated. James ‘lets Dante’s poetry shine in all its brilliance’. Moreover, the reader is carried along (a point not lost on Jane Goodall), and with a poem of this size the reader needs all the carrying they can get!

To be sure, it would be a great loss indeed if James’ rendering was the only one we had. But it’s not! And this means that fibre deficient highbrow ilk can take a chill pill, pour a wee dram and enjoy the astonishing offering on hand here. And for goodness sake, show some gratitude – the bloke’s been ploughing away on this work for decades!

Fiona Sampson correctly points out that the Comedy is best appreciated with a host of translations (Singleton’s pretty-flat-but-at-least-annotated version, or Ciardi’s pseudo-paraphrase, or Sinclair’s old English version, or Nichols’ excellent translation) alongside a copy of the magnificent lingua toscana itself – could there be a more perfect language for poetry? – and, I would add, at least one decent introduction (I like Sayers’) and a translation (like Musa’s) that includes some helpful critical apparatus. For, as one reviewer pointed out, not everyone is ‘au fait with 13th-century politics and religious struggle in Europe and the Italian peninsula’. And as another noted, ‘Dante requires at least some exegesis’. James, with genius, includes the footnotes and the exegesis in the text itself, and that without robbing the poem of its music.

Anyway, this grateful reader’s now heading back to his reading, and onwards to purgatory …

James Torrance on ‘Prayer and the Triune God of Grace’

In 1997, Professor James Torrance gave four lectures on the theme ‘Prayer and the Triune God of Grace’, a theme beautifully articulated in his essay ‘The Place of Jesus Christ in Worship’ (published in Theological Foundations for Ministry, edited by Ray Anderson) and in his 1994 Didsbury Lectures (published as Worship, Community, and the Triune God of Grace), among other places.

In 1997, Professor James Torrance gave four lectures on the theme ‘Prayer and the Triune God of Grace’, a theme beautifully articulated in his essay ‘The Place of Jesus Christ in Worship’ (published in Theological Foundations for Ministry, edited by Ray Anderson) and in his 1994 Didsbury Lectures (published as Worship, Community, and the Triune God of Grace), among other places.

The titles of the lectures were:

1. Prayer as Communion: Participating by Grace in the Triune Life of God

2. Prayer and the Priesthood of Christ

3. Different Models of Prayer: Stages in the Life of Prayer

4. Covenant God or Contract God: Is Prayer a Joy or a Burden?

I posted the links to these just over 4 years ago, but those links are now dead, and a number of people have contacted me recently asking me to make them available again. So here they are, resurrected!

Part 1 [MP3]

Part 2 [MP3]

Part 3 [MP3]

Part 4 [MP3]

Part 5 [MP3]

Part 6 [MP3]

The substance of the lectures – indeed, the substance of JB’s public ministry – is articulated in his hymn, ‘I know not how to pray, O Lord’:

1. I know not how to pray, O Lord,

So weak and frail am I.

Lord Jesus to Your outstretched arms

In love I daily fly,

For You have prayed for me.

2. I know not how to pray, O Lord,

O’erwhelmed by grief am I,

Lord Jesus in Your wondrous love

You hear my anxious cry

And ever pray for me.

3. I know not how to pray, O Lord,

For full of tears and pain

I groan, yet in my soul, I know

My cry is not in vain.

O teach me how to pray!

4. Although I know not how to pray,

Your Spirit intercedes,

Convincing me of pardoned sin;

For me in love He pleads

And teaches me to pray.

5. O take my wordless sighs and fears

And make my prayers Your own.

O put Your prayer within my lips

And lead me to God’s throne

That I may love like You.

6. O draw me to Your Father’s heart,

Lord Jesus, when I pray,

And whisper in my troubled ear,

‘Your sins are washed away.

Come home with Me today!’

7. At home within our Father’s house,

Your Father, Lord, and mine,

I’m lifted up by Your embrace

To share in love divine

Which floods my heart with joy.

8. Transfigured by Your glory, Lord,

Renewed in heart and mind,

I’ll sing angelic songs of praise

With joy which all can find

In You alone, O Lord.

9. I’ll love You, O my Father God,

Through Jesus Christ, Your Son.

I’ll love You in the Spirit, Lord,

In whom we all are one,

Made holy by Your love.

[For those who may be interested, I have included this hymn in my essay ‘“Tha mi a’ toirt fainear dur gearan”: J. McLeod Campbell and P.T. Forsyth on the Extent of Christ’s Vicarious Ministry’, published in Evangelical Calvinism: Essays Resourcing the Continuing Reformation of the Church (eds. Myk Habets and Robert Grow. Pickwick Publications, 2012).]

The 2014 Global Institute of Theology

My mate, Frans du Plessis, reminds me that it’s time to remind folk about the forthcoming meeting of the Global Institute of Theology:

The fourth Global Institute of Theology (GIT) is set to take place in San Jose, Costa Rica, 5–28 July 2014. The institute will be held in collaboration with and under the academic auspices of the Universidad Bíblica Latinoamericana (Latin American Biblical University).

The GIT is a bi-annual program by the World Communion of Reformed Churches (WCRC). Previously, it has been held in Ghana, United States, and Indonesia. The program is intended for theological students and pastors beginning their ministry. This year, up to 35 participants will be selected. Applicants should have a particular interest in ecumenical theology and mission. The WCRC will take necessary efforts to ensure that the student body will reflect gender and regional balance to represent the diversity of the Reformed family in the world today.

Through lectures, seminars, worship services, exposure visits, contextual experiences, the sharing of stories and participation in the life of the churches in Costa Rica, GIT participants will explore the theme of “Transforming Mission, Community, and Church.” Students will take part in a core course as well as two elective courses out of six possible choices.

“The ultimate goal of the GIT is to form a new generation of Reformed leaders who are fully aware of the faith dimension of contemporary challenges, including economic injustice and environmental destruction,” explains Douwe Visser, Executive Secretary for Theology at the WCRC, and Secretary of the GIT. “Costa Rica, a nation that set the goal to be climate neutral in 2021, and has been ranked number one in the ‘happy planet index’ will provide an interesting background for these discussions,” added Visser.

The GIT faculty will include, among others, Bas Plaisier (The Netherlands), Peter Wyatt (Canada), Aruna Gnanadason (India), Isabel Phiri (Malawi), Claudio Carvalhaes (United States), Philip Peacock (India), Hans de Wit (The Netherlands), and Roy May (United States).

Applications for the GIT will be accepted until 1 January 2014.

Further information can be obtained on the GIT website or via e-mail.

If you’re a young theologian who chooses to develop your work out of the Reformed tradition as ‘a matter of religious and theological conviction’ (to rip from James Gustafson), then I commend it highly.

Some stuff on the stove

- Steve Holmes’ little paper on ‘The Politics of Christmas’ is wonderful. (Our bible study group is planning to use it as a basis for discussion, and action, as we travel through Advent.)

- Tim Gombis shares some thoughts about what he’s learned about teaching.

- Ben Myers posts a delightful reflection about toes.

- One artist makes some great Banksy GIFs.

- David Hayward offers 10 indefinitive reasons for why leaving pastoral ministry is difficult.

- Some curry love.

- Barbara Fister thinks it’s time that libraries did something about the future of books. She also posts on judging journals.

- An interview with Rowan Williams on his debt to C. S. Lewis (HT: Paul Fromont).

- Speaking of RW, there’s also info on his forthcoming Gifford Lectures.

- Halden Doerge shares a sermon on Luke 18.1-6, ‘God’s Fiction: A Sermon of Vulnerability’

- Peter Leithart on Alexander Schmemann on the eucharist.

- Neville Callam, the General Secretary of the Baptist World Alliance, calls upon Baptists to revive the practice of the veneration of the saints:

Shouldn’t Baptist churches retrieve the practice of venerating the saints, that is, engaging in corporate worship acts designed not to worship the saints, but to remember, honor, learn from, and celebrate saints from our Baptist family and from other Christian communions? Until we regularly include commemoration of the saints in our worship celebrations, we will continue to neglect the opportunity to give proper value to those from our past who have borne courageous witness to faithful discipleship. Commemorative acts done in our Sunday morning services would provide a suitable accompaniment for the tradition some have already developed as part of their Vacation Bible School program, in which stories are told of great spiritual leaders worthy of emulation … [HT: Steven Harmon]

- Some good stuff here from Richard Bauckham, author of the tremendously helpful book The Theology of the Book of Revelation, speaking with Ben Witherington about the Book of Revelation:

[Image: from Old Picture of the Day]

‘God dies in the world’: an interview with an artist

The front cover of my most recent publication, Descending on Humanity and Intervening in History: Notes from the Pulpit Ministry of P. T. Forsyth, includes a section of a painting (above) by my daughter Sinead. The decision to use her painting – a decision which, to be sure, required some grovelling for permission – was not, I hope, motivated by cutesiness but rather by a profound sense of the work’s fittingness to the book’s themes. The painting, which is used upside down, is called ‘Crosses’.

Now that Sinead and I have both finally seen the book in real life, I wanted to ask her again about the painting, about what it ‘means’ (her word), and about how it relates to the material in daddy’s book. So while on the way to school this morning, I conducted a brief ‘interview’ with Sinead. As part of that conversation, Sinead offered the following statement:

Now that Sinead and I have both finally seen the book in real life, I wanted to ask her again about the painting, about what it ‘means’ (her word), and about how it relates to the material in daddy’s book. So while on the way to school this morning, I conducted a brief ‘interview’ with Sinead. As part of that conversation, Sinead offered the following statement:

God dies in the world, and the God who dies in the world is the same God who dies in heaven. And yet somehow these two deaths, which are really the same, are related. In the end, it’s all really a mystery – but in the mystery the church is created and the world is saved. And that’s what my painting is about.

I buzzed.

[Copies of the book are available here or via here or by contacting me directly. If you are interested in reviewing the volume, then please contact James Stock at Wipf and Stock. And if you are interested in a copy signed by Sinead, then it’ll probably cost ya some serious dosh, or a packet of mints!]

Review: Manifesto for Learning: The Mission of the Church in Times of Change

Donn Morgan, Manifesto for Learning: The Mission of the Church in Times of Change (New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2012). ISBN: 978-0-8192-2768-3; 96pp.

Donn Morgan, Manifesto for Learning: The Mission of the Church in Times of Change (New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2012). ISBN: 978-0-8192-2768-3; 96pp.

A guest-review by Kevin Ward.

This is a very brief little book that at first glance does not have much relevance for the church in New Zealand. It comes out of the crisis facing theological education in the US brought about by having far too many theological schools faced with rising costs, declining student numbers and reduced financial commitment from churches. That is a challenge for theological schools in New Zealand also, as I am aware both through teaching in one and being involved at executive level with both the New Zealand and Australia New Zealand Associations of such schools. However, as I read it I realised much of what was being discussed, both in terms of challenges and suggested ways ahead, was generally true for the church in New Zealand as well as theological education.

The core argument is that the mission of the church has three basic elements: worship, service and learning. He argues that while worship and service are regularly prioritised, learning is no longer regarded as ‘an important part of the church’s identity and mission’. ‘Service and worship without education and formation risks separating mission and ministry from fundamental parts of our identity, and creating a kind of amnesia concerning our Christian faith and its particular expressions’ (p. 38). This is a concern I also share and is identified in many recent studies, particularly among young people and young adults. Morgan takes a holistic view of this, not just concern about theological schools, and argues that the most important level of education is what happens at a congregational level. Here, in my observation, it is sadly neglected in many churches. The consequence of this lack of concern is, of course, a lack of commitment of resources to it, both at a congregational level and also in supporting theological education. Giving our scarce resources, service ministries or providing exciting worship is what counts.

The book is helpful in summarising some of the changes that have occurred over the past 50 years which have impacted on churches and theological schools in similar ways in New Zealand. ‘There continues to be debate about both the causes of and the solutions to the mainline churches’ decline. Because some churches continue to thrive, some say this is just a wake-up call for those in decline. But the overall numbers in many denominations reflect devastating change that would appear to require radical rethinking of the church’s mission, of “how to do and be church”’ (p. 17). Rather than thinking about these issues and the wider challenges of the state of the church as a whole, most focus has been on the survival of our particular community and its sustainability. This fosters a foxhole mentality. I would suggest this is true of both theological schools and local churches.

When it comes to looking at implementing the changes needed, Morgan suggests that it is like being in the middle of a three ring circus. The first ring represents the perennial issue of resources, especially financial, and the lack thereof. The second represents changes in church and society, which are, of course, related to the first. But while we spend much time discussing and obsessing about these, there is a third ring where ‘we try to put financial realities together with the changes in church and society as we reconsider mission and ministry’ (p. 61). This is the place where we need to not merely talk about structural change, but get through to doing it. This is the ring that is all-too-rarely entered. From my perspective it is a problem many theological schools have not addressed; namely, why a number in New Zealand have closed over recent years, and others are at crisis point (although I would add that it is one thing the Presbyterian Church has done well). But it is an even bigger issue for mainline churches, none more so than the PCANZ, and although we have been aware of the need for it for over a decade, have done precious little to address it.

The final chapter looks at some of the problems faced along the way of change, such as ‘inertia and investment in the status quo’, ‘particularity and diversity’, and ‘competition’, which are equally shared by churches and education schools. So while this book, at one level, is about challenges facing theological schools in the US, reading it provides many helpful insights and suggestions not only for similar institutions in New Zealand but also for the church in the very challenging context we find ourselves in, where time is no longer our friend.

Seminar on Debates about Religion and Sexuality

Between 10–19 June, 2014, the Harvard Divinity School is running a ‘summer seminar for scholars, other writers or artists, religious leaders, and activists who are working on a first large project in which they hope to change the terms of current debates around religion and sexuality’. The seminar will be directed by Mark D. Jordan (Washington University, St. Louis) and Mayra Rivera Rivera (Harvard University), is limited to 12 participants, and HDS is picking up the tab for travel, accommodation and grub.

Between 10–19 June, 2014, the Harvard Divinity School is running a ‘summer seminar for scholars, other writers or artists, religious leaders, and activists who are working on a first large project in which they hope to change the terms of current debates around religion and sexuality’. The seminar will be directed by Mark D. Jordan (Washington University, St. Louis) and Mayra Rivera Rivera (Harvard University), is limited to 12 participants, and HDS is picking up the tab for travel, accommodation and grub.

Applications are due 5 February, 2014, and questions may be directed to rsseminar@hds.harvard.edu.

More info here.

Review: Resilient Ministry: What Pastors Told Us About Surviving and Thriving

Bob Burns, Tasha D. Guthrie and Donald C. Guthrie, Resilient Ministry: What Pastors Told us about Surviving and Thriving (Downers Grove: IVP Books, 2013). ISBN: 978-0-8308-4103-5; 312pp.

Bob Burns, Tasha D. Guthrie and Donald C. Guthrie, Resilient Ministry: What Pastors Told us about Surviving and Thriving (Downers Grove: IVP Books, 2013). ISBN: 978-0-8308-4103-5; 312pp.

A guest-review by Kevin Ward.

This is a book which every person working as a minister of the gospel would benefit from reading – indeed, more than reading, but also reflecting on and, in light of that, making changes to how they live and work. We are all aware that many of those who enter ministry in response to what they perceive as a life time calling drop out within a relatively short period of time. Precious few of those I trained with nearly four decades ago are still in church ministry. What kills them off is not what goes into sermons or worship services but, as the authors of this book point out, matters of life skills, behaviour patterns and character. This book not only identifies the core issues but also makes suggestions of what needs to change and how to action that.

Rather than just building on anecdotal evidence or personal experience, the book is based on solid scientific research. The team created three pastoral peer groups or cohorts (who were primarily Presbyterian) who met three times a year for two years. They were interviewed to identify the ministry issues they wanted to discuss. They then read books on those subjects, listened to experts who were brought in and then discussed the issues in their groups. The discussions were recorded, transcribed and analysed.

From the transcripts, the researchers identified five themes that they believe are keys to sustaining pastoral excellence. These were:

1. Spiritual formation. Ministers can be so busy in the multiple tasks of ministry that they neglect their own spiritual wellbeing, the source from which ministry flows. They need to internalise the spiritual rhythms of reflection, worship, sabbath and prayer.

2. Self-care. The ongoing development of the whole person: physical, mental, emotional, relational. This involves a range of practical issues including identifying allies and confidants, establishing an exercise routine, planning intellectual development and holidays and creating and keeping good boundaries.

3. Emotional and cultural intelligence. These are related to being aware of oneself and also attentive to and aware of other people, places and social dynamics. Much has been written recently about the importance of emotional intelligence in leadership but the awareness of cultural intelligence, crucial in our increasingly diverse world, is only just emerging.

4. Marriage and family. Unlike many jobs ministers are never really ‘off the clock’, and so the demands of ministry can constantly intrude on marriage and family time. It is, then, critical to be intentional about giving focussed uninterrupted time to spouse and children. The significance of the contribution of the spouse to a minister’s resilience in ministry came through again and again.

5. Leadership and management. I found these chapters full of good insight and found helpful the way they talked about these as the ‘poetic’ and the ‘plumbing’ side of leadership, both of which are essential to good and resilient ministry. The management side can be found addressed in many books but the poetic side of leadership is much more intuitive and harder to explain and there are some helpful concepts here.

As well as having lots of good information the book has questions for personal evaluation and reflection throughout, as well as suggestions for further reading and exploring through media. This is an area I have taught in for the past 15 years or so, and this book is as a helpful as any I have come across. It is both informed and practical. As well as its personal use for ministers, it would be ideal for a group of ministers to read and discuss together and perhaps also to work through with the lay leadership in their church. I certainly intend using it as an important text for my students.

[Those interested in reading more on this topic might like to check out Jason’s series On the Cost and Grace of Parish Ministry]

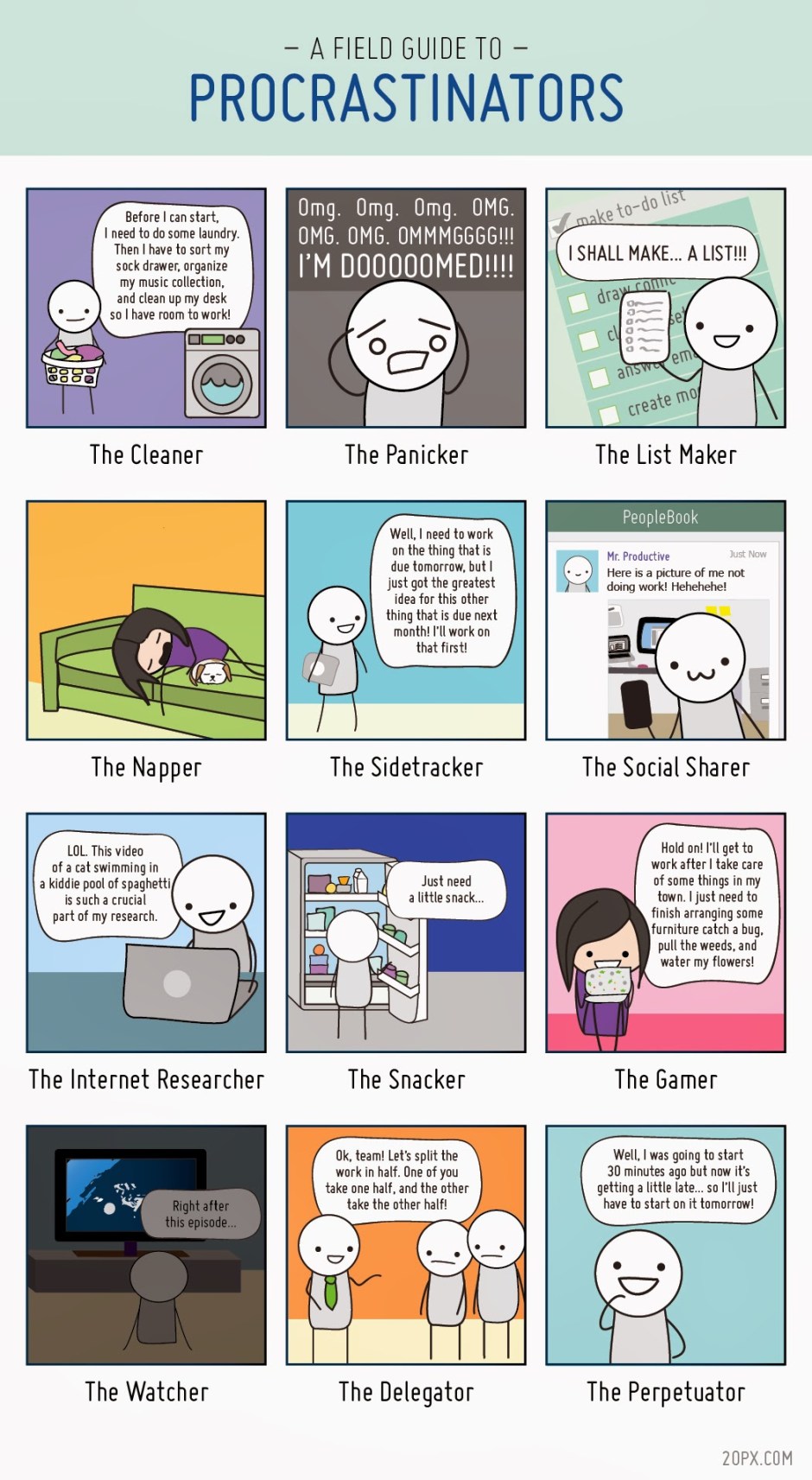

A field guide to procrastinators

Recently, here at PCaL, I shared a cartoon outlining various stages of procrastination. It proved to be so popular (I wish there was nearly as much interest in my more serious posts!) that I thought I’d post another one. So here’s an accompanying ‘field guide’: