- Scott Stephens on being Christian, government funding and chaplaincy in schools.

- When Did Girls Start Wearing Pink?

- J. Scott Jackson reviews David Haddorff’s Christian Ethics as Witness: Barth’s Ethics for a World at Risk.

- What Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart owes to his big sister, Maria Anna Mozart.

- Michael Jensen on ‘Is God a bloke?’, or on why ‘a Christianity that refuses to call God “Father” is something other than Christianity’.

- The future, according to Google search results.

- John Pilger on Anzac Day and Australia’s role as ‘deputy sheriff’.

- Scott Hamilton on New Zealand’s ‘endangered life form’ – the literary critic – and reviews on Private Bestiary.

- Garry Deverell posts on Holy Week and the Great Three Days of Easter – an introduction for the uninitiated.

- Halden Doerge details a Call for Papers for an AAR session on Jacob Taubes and Christian Theology.

- An excerpt from Žižek’s Living in the End Times.

- An Easter Message from Ricky Gervais.

Karl Barth

Barth on Mozart

‘… Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Why is it that this man is so incomparable? Why is it that for the receptive, he has produced in almost every bar he conceived and composed a type of music for which “beautiful” is not a fitting epithet: music which for the true Christian is not mere entertainment, enjoyment or edification but food and drink; music full of comfort and counsel for his needs; music which is never a slave to its technique nor sentimental but always “moving,” free and liberating because wise, strong and sovereign? Why is it possible to hold that Mozart has a place in theology, especially in the doctrine of creation and also in eschatology, although he was not a father of the Church, does not seem to have been a particularly active Christian, and was a Roman Catholic, apparently leading what might appear to us a rather frivolous existence when not occupied in his work? It is possible to give him this position because he knew something about creation in its total goodness that neither the real fathers of the Church nor our Reformers, neither the orthodox nor Liberals, neither the exponents of natural theology nor those heavily armed with the “Word of God,” and certainly not the Existentialists, nor indeed any other great musicians before and after him, either know or can express and maintain as he did. In this respect he was pure in heart, far transcending both optimists and pessimists. 1756–1791! This was the time when God was under attack for the Lisbon earthquake, and theologians and other well-meaning folk were hard put to it to defend Him. In face of the problem of theodicy, Mozart had the peace of God which far transcends all the critical or speculative reason that praises and reproves. This problem lay behind him. Why then concern himself with it? He had heard, and causes those who have ears to hear, even to-day, what we shall not see until the end of time—the whole context of providence. As though in the light of this end, he heard the harmony of creation to which the shadow also belongs but in which the shadow is not darkness, deficiency is not defeat, sadness cannot become despair, trouble cannot degenerate into tragedy and infinite melancholy is not ultimately forced to claim undisputed sway. Thus the cheerfulness in this harmony is not without its limits. But the light shines all the more brightly because it breaks forth from the shadow. The sweetness is also bitter and cannot therefore cloy. Life does not fear death but knows it well. Et lux perpetua lucet [light perpetual shines] (sic!) eis [upon them]—even the dead of Lisbon. Mozart saw this light no more than we do, but he heard the whole world of creation enveloped by this light. Hence it was fundamentally in order that he should not hear a middle or neutral note, but the positive far more strongly than the negative. He heard the negative only in and with the positive. Yet in their inequality he heard them both together, as, for example, in the Symphony in G-minor of 1788. He never heard only the one in abstraction. He heard concretely, and therefore his compositions were and are total music. Hearing creation unresentfully and impartially, he did not produce merely his own music but that of creation, its twofold and yet harmonious praise of God. He neither needed nor desired to express or represent himself, his vitality, sorrow, piety, or any programme. He was remarkably free from the mania for self-expression. He simply offered himself as the agent by which little bits of horn, metal and catgut could serve as the voices of creation, sometimes leading, sometimes accompanying and sometimes in harmony. He made use of instruments ranging from the piano and violin, through the horn and the clarinet, down to the venerable bassoon, with the human voice somewhere among them, having no special claim to distinction yet distinguished for this very reason. He drew music from them all, expressing even human emotions in the service of this music, and not vice versa. He himself was only an ear for this music, and its mediator to other ears. He died when according to the worldly wise his life-work was only ripening to its true fulfilment. But who shall say that after the “Magic Flute,” the Clarinet Concerto of October 1791 and the Requiem, it was not already fulfilled? Was not the whole of his achievement implicit in his works at the age of 16 or 18? Is it not heard in what has come down to us from the very young Mozart? He died in misery like an “unknown soldier,” and in company with Calvin, and Moses in the Bible, he has no known grave. But what does this matter? What does a grave matter when a life is permitted simply and unpretentiously, and therefore serenely, authentically and impressively, to express the good creation of God, which also includes the limitation and end of man.

‘… Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Why is it that this man is so incomparable? Why is it that for the receptive, he has produced in almost every bar he conceived and composed a type of music for which “beautiful” is not a fitting epithet: music which for the true Christian is not mere entertainment, enjoyment or edification but food and drink; music full of comfort and counsel for his needs; music which is never a slave to its technique nor sentimental but always “moving,” free and liberating because wise, strong and sovereign? Why is it possible to hold that Mozart has a place in theology, especially in the doctrine of creation and also in eschatology, although he was not a father of the Church, does not seem to have been a particularly active Christian, and was a Roman Catholic, apparently leading what might appear to us a rather frivolous existence when not occupied in his work? It is possible to give him this position because he knew something about creation in its total goodness that neither the real fathers of the Church nor our Reformers, neither the orthodox nor Liberals, neither the exponents of natural theology nor those heavily armed with the “Word of God,” and certainly not the Existentialists, nor indeed any other great musicians before and after him, either know or can express and maintain as he did. In this respect he was pure in heart, far transcending both optimists and pessimists. 1756–1791! This was the time when God was under attack for the Lisbon earthquake, and theologians and other well-meaning folk were hard put to it to defend Him. In face of the problem of theodicy, Mozart had the peace of God which far transcends all the critical or speculative reason that praises and reproves. This problem lay behind him. Why then concern himself with it? He had heard, and causes those who have ears to hear, even to-day, what we shall not see until the end of time—the whole context of providence. As though in the light of this end, he heard the harmony of creation to which the shadow also belongs but in which the shadow is not darkness, deficiency is not defeat, sadness cannot become despair, trouble cannot degenerate into tragedy and infinite melancholy is not ultimately forced to claim undisputed sway. Thus the cheerfulness in this harmony is not without its limits. But the light shines all the more brightly because it breaks forth from the shadow. The sweetness is also bitter and cannot therefore cloy. Life does not fear death but knows it well. Et lux perpetua lucet [light perpetual shines] (sic!) eis [upon them]—even the dead of Lisbon. Mozart saw this light no more than we do, but he heard the whole world of creation enveloped by this light. Hence it was fundamentally in order that he should not hear a middle or neutral note, but the positive far more strongly than the negative. He heard the negative only in and with the positive. Yet in their inequality he heard them both together, as, for example, in the Symphony in G-minor of 1788. He never heard only the one in abstraction. He heard concretely, and therefore his compositions were and are total music. Hearing creation unresentfully and impartially, he did not produce merely his own music but that of creation, its twofold and yet harmonious praise of God. He neither needed nor desired to express or represent himself, his vitality, sorrow, piety, or any programme. He was remarkably free from the mania for self-expression. He simply offered himself as the agent by which little bits of horn, metal and catgut could serve as the voices of creation, sometimes leading, sometimes accompanying and sometimes in harmony. He made use of instruments ranging from the piano and violin, through the horn and the clarinet, down to the venerable bassoon, with the human voice somewhere among them, having no special claim to distinction yet distinguished for this very reason. He drew music from them all, expressing even human emotions in the service of this music, and not vice versa. He himself was only an ear for this music, and its mediator to other ears. He died when according to the worldly wise his life-work was only ripening to its true fulfilment. But who shall say that after the “Magic Flute,” the Clarinet Concerto of October 1791 and the Requiem, it was not already fulfilled? Was not the whole of his achievement implicit in his works at the age of 16 or 18? Is it not heard in what has come down to us from the very young Mozart? He died in misery like an “unknown soldier,” and in company with Calvin, and Moses in the Bible, he has no known grave. But what does this matter? What does a grave matter when a life is permitted simply and unpretentiously, and therefore serenely, authentically and impressively, to express the good creation of God, which also includes the limitation and end of man.

I make this interposition here, before turning to chaos, because in the music of Mozart—and I wonder whether the same can be said of any other works before or after—we have clear and convincing proof that it is a slander on creation to charge it with a share in chaos because it includes a Yes and a No, as though orientated to God on the one side and nothingness on the other. Mozart causes us to hear that even on the latter side, and therefore in its totality, creation praises its Master and is therefore perfect. Here on the threshhold of our problem—and it is no small achievement—Mozart has created order for those who have ears to hear, and he has done it better than any scientific deduction could’.

— Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III/3 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2004), 297–99.

Thomas Aquinas and Karl Barth: An Unofficial Protestant-Catholic Dialogue

The Center for Barth Studies at Princeton Theological Seminary and the Thomistic Institute of the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception at the Dominican House of Studies, in cooperation with the Karl Barth Society of North America are organising what promises to be a wonderfully stimulating conference, to be held at Princeton. More information is available here.

The Center for Barth Studies at Princeton Theological Seminary and the Thomistic Institute of the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception at the Dominican House of Studies, in cooperation with the Karl Barth Society of North America are organising what promises to be a wonderfully stimulating conference, to be held at Princeton. More information is available here.

Around: ‘And I am dumb to tell a weather’s wind/How time has ticked a heaven round the stars’

- Wonderful stuff by Slavoj Žižek on the miracle of Tahrir Square

- Fascinating pieces by Bert Olivier on Egypt: The crisis of modernity all over again?, and on Panopticism, Facebook, the ‘information bomb’, and Wikileaks

- Immanuel Kant’s guide to a good dinner party

- Jason Byassee on mentoring people with books

- David Gambrell on welcoming children in worship

- The 2011 Barth Conference is on the theme ‘Thomas Aquinas and Karl Barth: An Unofficial Protestant-Catholic Dialogue’

- On the subject of conferences, registrations for the ‘”Tikkun Olam” – to mend the world’ conference and exhibition are now open. This is shaping up to be a really exciting event.

- Kent Eilers offers ‘four handles’ on reading Barth

- The so-called ‘Romero Prayer’, by John Cardinal Dearden:

It helps, now and then, to step back and take a long view.

The kingdom is not only beyond our efforts,

it is even beyond our vision.

We accomplish in our lifetime only a tiny fraction

of the magnificent enterprise that is God’s work.

Nothing we do is complete, which is a way of saying

that the kingdom always lies beyond us.

No statement says all that could be said.

No prayer fully expresses our faith.

No confession brings perfection.

No pastoral visit brings wholeness.

No program accomplishes the church’s mission.

No set of goals and objectives includes everything.

This is what we are about.

We plant the seeds that one day will grow.

We water seeds already planted,

knowing that they hold future promise.

We lay foundations that will need further development.

We provide yeast that produces far beyond our capabilities.

We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation

in realizing that. This enables us to do something,

and to do it very well. It may be incomplete,

but it is a beginning, a step along the way,

an opportunity for the Lord’s grace to enter and do the rest.

We may never see the end results, but that is the difference

between the master builder and the worker.

We are workers, not master builders; ministers, not messiahs.

We are prophets of a future not our own.

Amen.

Jack Clemo, ‘On the Death of Karl Barth’

He ascended from a lonely crag in winter,

His thunder fading in the Alpine dusk;

And a blizzard was back on the Church,

A convenient cloak, sprinkling harlot and husk –

Back again, after all his labour

To clear the passes, give us access

Once more to the old prophetic tongues,

Peak-heats in which man, time, progress

Are lost in reconciliation

With outcast and angered Deity.

He has not gone silenced in defeat:

The suffocating swirl of heresy

Confirms the law he taught us; we keep the glow,

Knowing the season, the rhythm, the consummation.

Truth predicts the eclipse of truth,

And in that eclipse it condemns man,

Whose self-love with its useful schools of thought,

Its pious camouflage of a God within,

Is always the cause of the shadow, the fall, the burial,

The smug rub of hands

Amid a reek of research.

The cyclic, well-meant smothering

Of the accursed footprints inside man’s frontier;

The militant revival,

Within time and as an unchanged creed,

Of the eternal form and substance of the Word:

This has marked Western history,

Its life’s chief need and counter-need,

From the hour God’s feet shook Jordan.

We touched His crag of paradox

Through our tempestuous leader, now dead,

Who ploughed from Safenwil to show us greatness

In a God lonely, exiled, homeless in our sphere,

Since his footfall breeds guilt, stirs dread

Of a love fire-tongued, cleaving our sin,

Retrieving the soul from racial evolution,

Giving it grace to mortify,

In deeps or shallows, all projections of the divine.

– Jack Clemo, ‘On the Death of Karl Barth’ in The New Oxford Book of Christian Verse (ed. Donald Davie; Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 291–2.

Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth: A Review

Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth, by David Gibson. Pp. xiii + 221. London/New York: T&T Clark, 2009, ISBN 9 780567 468741.

Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth, by David Gibson. Pp. xiii + 221. London/New York: T&T Clark, 2009, ISBN 9 780567 468741.

In the summer of 1922, the young Karl Barth taught a course on the theology of Calvin. As he struggled to prepare lectures, he immersed himself passionately in Calvin’s thought – even cancelling his other announced course (on the Epistle to the Hebrews) so that he could concentrate solely on the Reformer’s writings. In a letter penned to Eduard Thurneysen that same year, Barth expressed his astonishment at the strangeness and power of what he had discovered: ‘Calvin is a cataract, a primeval forest, a demonic power, something directly down from Himalaya, absolutely Chinese, strange, mythological; I lack completely the means, the suction cups, even to assimilate this phenomenon, not to speak of presenting it adequately. What I receive is only a thin little stream and what I can then give out again is only a yet thinner extract of this little stream. I could gladly and profitably set myself down and spend all the rest of my life just with Calvin’. Certainly any project which attempts to bring these two giants into conversation is, to say the least, ambitious; particularly, perhaps, when it comes to their respective doctrines of election.

Unprepared to simply accept various readings of Calvin’s and Barth’s doctrines of election, David Gibson, in a ‘lightly revised version’ (p. xi) of his PhD dissertation completed at the University of Aberdeen under the supervision of Francis Watson, turns to Calvin’s corpus (particularly to his commentaries and to the Institutes) and to Barth (CD II/2 principally) in order to investigate and then compare their respective articulations of the doctrine, and to enquire about what relationship election has with christology in their projects. Moreover, Gibson is concerned to attend carefully to their exegeses, and to the ‘role of text-reception in theological construction’ (p. 11) in both thinkers. His argument is that ‘the exegetical presentations of Christology and election in Calvin and Barth expose a contrasting set of relationships between these doctrinal loci in each theologian’ (p. 1) and that this differing relationship between the two doctrines flows from and informs two contrasting approaches to the interpretation of Scripture. Gibson helps his readers appreciate how, for both Calvin and Barth, doctrine and exegesis are not tasks to be taken in isolation, but are, rather, united around, in different ways, the subject of their enquiry; namely, Jesus Christ and the caelesti decreto.

Employing and qualifying Richard Muller’s distinction between ‘soteriological christocentrism’ (so Calvin) and ‘principial christocentrism’ (so Barth), Gibson suggests a corresponding hermeneutical distinction – ‘extensive’ and ‘intensive’. A ‘Christologically extensive’ hermeneutic is evident, Gibson contends, when ‘the centre of Christology points outwards to other doctrinal loci which have space and scope to exist in themselves at a measure of distance from Christology and from each other’. Here christology ‘may influence and shape’ other loci, but christology neither dictates nor controls them. This, Gibson argues, represents Calvin’s christology. Conversely, a ‘Christologically intensive’ hermeneutic describes when ‘the christological centre defines all else within its circumference. Within this circle, Christology draws everything else to itself so that all other doctrinal loci cannot be read in Scripture apart from explicit christological reference’ (p. 15). So Barth, whose intensively christological hermeneutic ‘privileges the name of Jesus Christ in ways which go significantly beyond Calvin’s understanding of how Christology functions in exegesis’ (p. 27).

Gibson traces these two distinctions through Calvin’s and Barth’s approaches to christology, election and hermeneutics, illustrating that while much of the same grammar is employed, and many of the same biblical texts examined, and while their respective exegeses of election exist within ‘christological horizons which show how doctrine itself may be a hermeneutic’ (p. 16), Calvin and Barth often sing in different keys, and at times different songs though with no less exegetical reasoning in either.

In Chapter 2 – ‘Christology and Election’ – Gibson deepens his basic thesis by further sketching the relationship between Christ and election in Calvin’s and Barth’s exegeses. He argues that, while Barth’s position is not as radical as some recent interpreters have claimed, Barth’s understanding of the pre-existent Jesus as the subject of election sponsors two different understandings of election’s trinitarian basis than we see in Calvin. Gibson’s basic point here is that Calvin’s christocentrism emerges as distinctively soteriological while Barth’s is radically principial: ‘Calvin’s theology allows us to speak of Christ and the decree, but Barth’s theology to say that Christ is the decree’ (p. 30).

In Chapter 3, Gibson illustrates his thesis in detail by outlining Calvin’s and Barth’s reading and use of Romans 9–11. He shows that both theologians operate with different understandings of the relationship between covenant and election because of the location that each grants to christology. This leads to two contrasting ideas of Israel’s vocation and relationship to the Church. Moreover, whereas for Barth, Christ himself is the subject of election, and for whose sake Israel’s election occurs, Calvin reads Romans 9–11 as an exposition of the eternal decree in which christology recedes into the background. In other words, christology, for Calvin, is concerned with the economy of salvation rather than, as it is for Barth, with the eternal ground of salvation itself. Gibson concludes the chapter by asserting that ‘whereas for Calvin, Israel is typological of the church, for Barth both Israel and the church are typological of Christ, so that both forms of the community are “initially the two different but then inseparably related aspects of the fulfilment of the one covenant of grace in Christ”. These radically different conceptions of the covenant in Calvin and Barth issue directly from different forms of christocentrism’ (p. 153).

Gibson turns then in the final chapter to survey how christology shapes the way that his two subjects read Scripture. His aim here again is to show how Calvin’s christologically-extensive theology of interpretation explains how he intends election to be read in Scripture, and how this differs from Barth’s christologically-intensive approach. Gibson describes the latter’s reading of election as a ‘hermeneutic of patience and complexity, of interaction between the individual, multi-faceted predestinarian texts and the christological whole of which they are a part’ (p. 192). He also explores how ‘underlying these different hermeneutical approaches are two fundamentally different conceptions of the doctrine of revelation’ (p. 155).

There is much to commend about Gibson’s study: (i) He offers the reader a clear, careful and fair reading of Calvin and Barth on a doctrine that is, in the latter’s words, ‘the sum of the Gospel’ (CD II/2, p. 3); (ii) He is refreshingly appreciative of the ways in which the connections and motifs internal to Barth’s own thought are deeply indebted to the Reformed tradition, and particularly to Calvin: ‘For all his independent and creative genius, Barth’s theology is profoundly catholic, soaked in dialogue and debate with centuries of tradition and modulated with a Reformed accent’ (p. 18); (iii) The comparative reading (in §3) of Romans 9–11 yields much that is fruitful, and superbly illustrates the thesis of the entire volume. But, to my mind, the supreme value of Gibson’s study is (iv) the reminder – and there is little doubt that current Calvin and Barth scholarship needs such! – that at core, both Calvin and Barth are exegetes of Scripture, and that the neglect of the exegetical contours which shape their respective dogmatic projects is ruinous to providing a faithful reading of their corpuses. ‘For both interpreters, Holy Scripture is the quarry from which their dogmatic structure for election is hewn. Repeatedly, in the writings of both theologians, the emphasis on reception – it is in Scripture and not in their own theologizing that election is properly learned – is accompanied with a stress on right reception’ (p. 198). Gibson also addresses a brief word to contemporary Barth scholarship: ‘It is likely that where Barth’s doctrine of election is debated without attention to his practice as an exegete, and specifically to the very question which mattered most to him – “Does it stand in Scripture?” – then a debate occurs within parameters which Barth himself would not have recognized’ (p. 199). Such an approach is to be enthusiastically welcomed.

There are, however, a few less-satisfying aspects of what is otherwise a very valuable study. I will name five: (i) To my mind, Gibson appropriates too uncritically Muller’s reading of Calvin, and those readers less confident that Muller has read Calvin rightly may well be left wondering just how robust Gibson’s argument is; (ii) The focus of Gibson’s treatment of Barth tends to be too narrowly focused on CD II/2 and so neglects to attend to the nuances and developments in Barth’s understanding and articulation of election in other places. This leads at times to a flatter presentation of Barth’s (and of Calvin’s) thought than if greater attention had been paid to the historical and polemical natures of their projects. In Barth’s case, for example, of the way that his ‘principial christocentrism’ serves as protest to post-Kantian theology; (iii) Not a few readers will be disappointed that there is so little engagement with the secondary literature. For example, while Matthias Gockel’s and Suzanne McDonald’s PhD theses on Barth and T.F. Torrance’s study on Calvin’s hermeneutics are less concerned with the detail of biblical exegesis in their subjects than is Gibson, Gockel’s project is quickly dismissed (on p. 26) and any engagement with McDonald’s and Torrance’s work, and the kinds of systematic terrain that they are concerned to explore, is noticeably absent from Gibson’s essay. They would, if handled carefully, inform and strengthen its own foci; (iv) Most readers would no doubt prefer that extended quotations in Latin be accompanied with translation; and (v) Finally, Gibson resists offering any substantial critique or evaluation of his subjects’ method and doctrinal conclusions. Such may have served to draw out in constructive detail some of the places where Calvin and Barth are less than rewarding to us.

These reservations aside, this study deserves a wide reading, and will be of particular interest to Calvin and Barth scholars, to those interested in the development of the theo-logic of the doctrine of election in the Reformed tradition, and to those who are interested in seeing how two of that tradition’s major voices – one early modern and one late modern – read and used the Bible.

On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part VII

In his book, Called to Be Human: Letters to My Children on Living a Christian Life, Michael Jinkins tells of a letter that he received from a young minister. [BTW: I highly recommend Jinkins’ wonderful wee book, Letters to New Pastors]. This young minister recalls how he loves being a pastor, but is struggling to find his way through a long and bitter church conflict. Meanwhile, a variety of routine pastoral crises keep nipping like Chihuahuas at his heels. And, in the midst of all of this, he and his young wife are coping with the wondrous and life-changing event of the arrival of their first baby. The letter went on to highlight that his life had become so off kilter that he had almost completely lost the joy he knew when he entered the ministry. Jinkins’ response was to recall that ‘learning to live a balanced life is never easy, and even joyful events can sometimes contribute to life’s crises. But finding balance in the life of ministry – and this includes the preparation for ministry – is one of the greatest challenges of this vocation’. Jinkins cites Calvin’s view that ultimately it is our calling that sustains us in ministry. ‘But sometimes it is hard to sort through the accumulation of life’s debris, the flotsam and jetsam that move with every new tide’.

In his book, Called to Be Human: Letters to My Children on Living a Christian Life, Michael Jinkins tells of a letter that he received from a young minister. [BTW: I highly recommend Jinkins’ wonderful wee book, Letters to New Pastors]. This young minister recalls how he loves being a pastor, but is struggling to find his way through a long and bitter church conflict. Meanwhile, a variety of routine pastoral crises keep nipping like Chihuahuas at his heels. And, in the midst of all of this, he and his young wife are coping with the wondrous and life-changing event of the arrival of their first baby. The letter went on to highlight that his life had become so off kilter that he had almost completely lost the joy he knew when he entered the ministry. Jinkins’ response was to recall that ‘learning to live a balanced life is never easy, and even joyful events can sometimes contribute to life’s crises. But finding balance in the life of ministry – and this includes the preparation for ministry – is one of the greatest challenges of this vocation’. Jinkins cites Calvin’s view that ultimately it is our calling that sustains us in ministry. ‘But sometimes it is hard to sort through the accumulation of life’s debris, the flotsam and jetsam that move with every new tide’.

Jinkins then turns to Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic, impressed as he is with the wisdom, sensitivity and humanity evidenced in the Roman Stoic philosopher’s Epistulae morales ad Lucilium. Reflecting on Seneca’s Letters, Jinkins writes:

Jinkins then turns to Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic, impressed as he is with the wisdom, sensitivity and humanity evidenced in the Roman Stoic philosopher’s Epistulae morales ad Lucilium. Reflecting on Seneca’s Letters, Jinkins writes:

‘Too often, it seems to me, Christians fail to treasure the fact that we are human … Maybe the reason we lose our balance in the first place is related to the fact that we under-appreciate our humanity, that we as Christians forget that we are human. We treat our bodies with contempt. We ignore our limitations. We indulge in the self-destructive myth of our own indispensability. And we violate the sacred principle of Sabbath. Then we go to our physicians or our therapists or our pharmacists asking them to calm the symptoms of the illnesses we have induced, without any intention of dealing with the underlying causes’. (p. 119)

One of the things that Jinkins proceeds to reflect on concerns the deep relationship between friendship and a thoroughly-human life. And here he again cites Seneca:

‘There are certain people who tell any person they meet things that should only be confided to friends, unburdening themselves of whatever is on their minds into any ear they please. Others again are shy of confiding in their closest friends, and would not even let themselves, if they could help it, into the secrets they keep hidden deep down inside themselves. We should do neither. Trusting everyone is as much a fault as trusting no one … Similarly, people who never relax and people who are invariably in a relaxed state merit your disapproval – the former as much as the latter. For a delight in bustling about is not industry – it is only the restless energy of a hunted mind. And the state of mind that looks on all activity as tiresome is not true repose, but a spineless inertia’.

Jinkins appreciates Seneca’s warning us to be ‘attentive to the hidden compulsions that drive us’, and he recounts how the experience of CPE (which I wish was compulsory for all our interns in the PCANZ) was so helpful here. It was in CPE – where he experienced being peeled like an onion – that Jinkins learned that ‘the success of my theological education depended on the success of an even more basic human education, the education which Kierkegaard describes as the curriculum a person “goes through in order to catch up with himself.” Anyone, Kierkegaard writes, “who will not go through this course [of study] is not much helped by being born in the most enlightened age”’. Jinkins continues:

Jinkins appreciates Seneca’s warning us to be ‘attentive to the hidden compulsions that drive us’, and he recounts how the experience of CPE (which I wish was compulsory for all our interns in the PCANZ) was so helpful here. It was in CPE – where he experienced being peeled like an onion – that Jinkins learned that ‘the success of my theological education depended on the success of an even more basic human education, the education which Kierkegaard describes as the curriculum a person “goes through in order to catch up with himself.” Anyone, Kierkegaard writes, “who will not go through this course [of study] is not much helped by being born in the most enlightened age”’. Jinkins continues:

‘The compulsions that lead us to talk when we should be silent and to be silent when we should speak, the compulsions that drive us to inappropriate actions and inappropriate inaction can only be dealt with when we find the courage to name them. Iwas unable to find the courage to name these compulsions and to deal with them until I knew (really knew!) that there is nothing in the world that can separate us from the love of God. The balanced life is a life liberated (or at least on the road to being liberated) from the unseen, unexamined compulsions and hidden forces that toss and turn us. Seneca understood the dangers of those inner forces and compulsions, although we have a real advantage over him in that we know something about God’s grace that can liberate us from them. Seneca also understood the importance of friendship for living a balanced life. C.S. Lewis in a letter to his friend Arthur Greeves called friendship “the greatest of worldly goods.” Lewis told his friend, “Certainly to me [friendship] is the chief happiness of life. If I had to give a piece of advice to a young [person] about a place to live, I think I should say, ‘sacrifice almost everything to live where you can be near your friends”’.

The calling to pastoral ministry can and often does separate us geographically – and sometimes in other ways too – from those we love. But we need friends. I remember Geoffrey Bingham once commenting that pastors are expected to be friends to all, but few have any friends of their own. Might it be that one of the main contributors to clergy burnout is a paucity of friends? Effective pastoral ministry is impossible apart from friendship precisely because human flourishing is impossible apart from friendship. Only non-human pastors can go it alone, those particularly uninterested in being associated with the imago dei in creation.

While doing some study recently on 2 Timothy, I was struck by the depth of affection in Paul (or the author) for Timothy, who he remembers ‘constantly in [his] prayers night and day’ (1.3). Recalling Timothy’s tears, Paul writes of longing to see Timothy in order to be ‘filled with joy’ (1.4). Paul is concerned that Timothy may be embarrassed by his current state in prison and invites Timothy to join with him in ‘suffering for the gospel’ (1.8). Paul also notes with pain the abandonment of those in Asia who turned away from him (naming Phygelus and Hermogenes), and with thanksgiving the ‘household of Onesiphorus, because he often refreshed me and was not ashamed of my chain’, recalling that ‘when Onesiphorus arrived in Rome, he eagerly searched’ for Paul and found him (1.15–17). Throughout the letter, Paul proceeds to encourage Timothy to stay steadfast to the truth of the gospel, to ‘proclaim the message with persistence whether the time is favourable or unfavourable’ (4.2), and to resist the temptation to abandon the ministry of the word, reminding him that such a determination will come at cost, and that ‘all who want to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted’ (3.12). It strikes me that this is the tone of a true friend and fellow worker. The letter closes with Paul’s personal appeal to Timothy to ‘do your best to come to me soon’ (4.9), ‘do your best to come before winter’ (4.21), and not only come yourself but also bring Mark along as well (4.11). Moreover, ‘when you come’, Paul writes, ‘bring the cloak that I left with Carpus at Troas, also the books, and above all the parchments’ (4.13). I repeat: Effective pastoral ministry is impossible apart from friendship (and possibly parchments!).

While reading 2 Timothy, I remembered Barth’s comments in the Preface to Church Dogmatics III/4 where he expresses gratitude for ‘so much understanding and confidence, comfort and encouragement, friendship and co-operation, from so many people … both near and in many distant places (even in Germany, with a fidelity which I find very moving) … [who] in writing, in print, by telegraph and over the air .. moved, shamed and delighted’ him (pp. xiii–xiv). And later on in the same volume, he writes of the real honour of friendship, the koinonia in the ministry entrusted by God, reminding us that friendship is a gift of our union in the one Mediator Jesus Christ:

While reading 2 Timothy, I remembered Barth’s comments in the Preface to Church Dogmatics III/4 where he expresses gratitude for ‘so much understanding and confidence, comfort and encouragement, friendship and co-operation, from so many people … both near and in many distant places (even in Germany, with a fidelity which I find very moving) … [who] in writing, in print, by telegraph and over the air .. moved, shamed and delighted’ him (pp. xiii–xiv). And later on in the same volume, he writes of the real honour of friendship, the koinonia in the ministry entrusted by God, reminding us that friendship is a gift of our union in the one Mediator Jesus Christ:

‘It is in service that two men learn to know and respect one another, not by simply observing or thinking about one other, or even by living with one another, however great their concord or even friendship, in indolence or caprice, self-will or arrogance. So long as it depends on these factors, they can only underestimate or overestimate one another and miss the real honour which they both have, since each can only miss his own honour. Mere companions and comrades cannot appreciate either their own honour or that of the other. The honour of two men is disclosed and will be apparent to both when they meet each other in the knowledge that they are both claimed, not by and for something of their own and therefore incidental and non-essential, but for and by the service which God has laid upon them. This alone is the school of true self-estimation and mutual respect. But it really is this’. (CD III/4, 659)

But Barth also warns of the danger of making an idol out of friendship. Only in Christ is friendship free from the tyrannies of idolatry, and the consequent pain birthed when the idols topple, as is inevitable. In the anxieties that attend the condition called ‘being human’, Barth suggests, in CD IV/2, that such anxiety relates firstly to our ‘ignorance of God’, our ‘unwillingness to honour and love [God] as God’ (p. 475), to be, as he writes elsewhere, ‘friends of God’ (‘Our truth is our being in the Son of God, in whom we are not enemies but friends of God …’. CD II/2, 158; cf. CD II/2, 344, 745; CD III/3, 285–87; CD III/4, 40, 503, 576; CD IV/1, 251, 432). He continues:

‘In his anxious care man has secured and bolted himself against God from the very outset. He thinks that he can and should deal with God as if He were not God but a schema or shadow which he has projected on the wall. Is it not inevitable, then, that he should not have hearing ears or seeing eyes for His self-revelation? How can he believe in Him and love Him and hope in Him and pray to Him, however earnestly he may be told, or tell himself, that it is good and right to do this, and however sincerely he may wish to do so? In his care he blocks up what is for him too open access to the fountain which flows for him. Care makes a man stupid.

But when we turn to the horizontal plane care also destroys human fellowship. It does this in virtue of the unreality of its object. The ghost of the threat of a death without hope has no power to unite and gather. It is not for nothing that it is the product of the man who isolates himself from God. As such it necessarily isolates him from his fellow-men. It not only does not gather us but disperses and scatters us. It represents itself to each one in an individual character corresponding to the burrow from which he looks to the future and seeks to grasp its opportunities and ward off its dangers. Care does not unite us. It tears us apart with centrifugal force. We can and will make constant appeals to the solidarity of care, and constant attempts to organise anxious men, reducing their fears and desires to common denominators and co-ordinating their effects. But two or three or even millions of grains of sand, however tightly they may be momentarily compressed, can never make a rock. Anxious man is a mere grain of sand. Each individual has his own cares which others cannot share with him and which do not yield to any companionship or friendship or fellowship or union or brotherhood, however soundly established. By his very nature he is isolated and lonely at heart and therefore in all that he does or does not do. Even in society with others he secretly cherishes his own fears and desires. His decisive expectation from others is that they will help him against the threat under which he thinks he stands. And it is just the same with them too. Cares can never be organised and co-ordinated in such a way as to avoid mutual disappointment and distrust and final dissolution. And behind disappointment and distrust there lurks, ready to spring, the hostility and enmity and conflict of those who are anxious. It is a rare accident if different cares, although not really uniting, do at least run parallel and thus do not lead to strife. For the most part, however, they do not run parallel for long, but soon intersect. And, unfortunately, they do not do so in infinity, but in the very concrete encounters of those who are anxious. What is thought to be the greater anxiety of the one demands precedence over what is supposed to be the lesser anxiety of the other. The desires of the one can be fulfilled only at the expense of the desires of the other. Or the intersection is because they fear very different things, or – even worse – because the one desires what the other fears, or the one fears most of all what the other desires most of all. It is only a short step from a fatal neutrality to the even more fatal rivalry of different cares and those who are afflicted by them. If care itself remains – and it always does, constantly renewing itself from the source of the false opinion of human temporality – we find ourselves willy-nilly on this way in our mutual relationships, and we have no option but to tread it. There can be no genuine fellowship of man with man. There can only be friction and quarrelling and conflict and war. Care dissolves and destroys and atomises human society. In its shadow there can never arise a calm and stable and positive relationship to our fellow and neighbour and brother. It awakens the inhuman element within us’. (pp. 476–77)

So one is a friend when they have ‘the freedom, the ability, to be spontaneously good to another – a voluntary friend of God and therefore of [others]. As such [a person] does not do anything alien or accidental. [One] is not “friendly” amongst other things – casually – when [one] gives [themselves] to God and [to their brother or sister. One] does that which is most proper to him [or her. One] loves in doing it’ (CD IV/2, 833).

To return to Jinkins: Jinkins rightly notes that ‘friends keep us in balance. Friends keep us from taking ourselves too seriously. Often a friend’s laughter is a signpost pointing to our own absurdity, turning the light of grace on a fault so we can correct it. A friend may be the only person who loves you enough to read your sermon manuscript for the next week and tell you: “I know how you feel; but you shouldn’t say that in your sermon.” Or, “I agree with you and I’d be angry too; but don’t mail that letter.” Or, “I understand why you feel the way you do; but for God’s sake don’t do this.” On the high wire of life and Christian ministry, there are times when the net below us is unsure and the wire on which we balance has become frayed. Sometimes the only thing that we have to steady ourselves is a friend’s voice. The words may be spoken in reproof or in comfort. But if you know they are spoken in friendship, they may just save you from yourself’.

In a follow up letter to his son Jeremy, Jinkins again picks up on Seneca and the so-called ‘balanced life’, noting that ‘the life to which we are called in Jesus Christ is not necessarily a balanced life. The Christian life (and this extends to the life of Christian ministry) is, in a way, a profoundly unbalanced life. The Christian life is not simply the life of moderation described by Seneca the Stoic. The Christian life is a life of holy excess – not fanaticism, but excess nonetheless’. To illustrate, he cites from a diary that Reinhold Niebuhr kept as a young pastor (published as Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic) wherein Niebuhr wrote of himself:

In a follow up letter to his son Jeremy, Jinkins again picks up on Seneca and the so-called ‘balanced life’, noting that ‘the life to which we are called in Jesus Christ is not necessarily a balanced life. The Christian life (and this extends to the life of Christian ministry) is, in a way, a profoundly unbalanced life. The Christian life is not simply the life of moderation described by Seneca the Stoic. The Christian life is a life of holy excess – not fanaticism, but excess nonetheless’. To illustrate, he cites from a diary that Reinhold Niebuhr kept as a young pastor (published as Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic) wherein Niebuhr wrote of himself:

‘I am not really a Christian … I am too cautious to be a Christian. I can justify my caution, but so can the other fellow who is more cautious than I am. The whole Christian adventure is frustrated continually not so much by malice as by cowardice and reasonableness … A reasonable person adjusts his moral goal somewhere between Christ and Aristotle, between an ethic of love and an ethic of moderation. I hope there is more of Christ than of Aristotle in my position. But I would not be too sure of it’.

And later in this same diary, Niebuhr says: ‘It is almost impossible to be sane and Christian at the same time, and on the whole I have been more sane than Christian. I have said what I believe, but in my creed the divine madness of a gospel of love is qualified by considerations of moderation which I have called Aristotelian, but which an unfriendly critic might call opportunistic’.

Most of us, I suspect, operate how Jinkins describes himself: as benefiting greatly from our reading of the Stoics, but preferring to dine with the Epicureans. Or what is probably more accurate is that we live in a tension between ‘the good life’ as defined by the ancient Greek philosophers and ‘the call of Jesus Christ’ to take up our cross and follow him. ‘There is indeed something of a “divine madness” about the gospel of Jesus Christ. There is an outlandish, outrageous, insane extravagance about God’s mercy that acts without reservation and without the expectation of getting anything in return. But it is precisely in this holy madness that God reveals his own humanity, and shares it with us’ (p. 125).

I plan to return to this question of friendships in a latter post. But for now, it’s time to re-read 2 Corinthians, … and Dostoevsky, … and MacKinnon …

◊◊◊

Other posts in this series:

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part I

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part II

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part III

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part IV

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part V

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part VI

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part VIII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part IX

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part X

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XI

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XIII

- On the cost and grace of parish ministry – Part XIV

‘Joy is the serious business of Heaven’

This morning I was at St Margaret’s in Frankton (part of the Wakatipu Community parish) where I met some wonderful folk, resisted going fishing, and preached on Luke 15:1–10. The sermon was partly inspired by these words on joy by CS Lewis, and those of Karl Barth on the miracle of the love of God:

This morning I was at St Margaret’s in Frankton (part of the Wakatipu Community parish) where I met some wonderful folk, resisted going fishing, and preached on Luke 15:1–10. The sermon was partly inspired by these words on joy by CS Lewis, and those of Karl Barth on the miracle of the love of God:

‘I do not think that the life of Heaven bears any analogy to play or dance in respect of frivolity. I do think that while we are in this ‘valley of tears,’ cursed with labour, hemmed round with necessities, tripped up with frustrations, doomed to perpetual plannings, puzzlings, and anxieties, certain qualities that must belong to the celestial condition have no chance to get through, can project no image of themselves, except in activities which, for us here and now, are frivolous. For surely we must suppose the life of the blessed to be an end in itself, indeed The End: to be utterly spontaneous; to be the complete reconciliation of boundless freedom with order – with the most delicately adjusted, supple, intricate, and beautiful order? How can you find any image of this in the ‘serious’ activities either of our natural or of our (present) spiritual life? – either in our precarious and heart-broken affections or in the Way which is always, in some degree, a via crucis?: No, Malcolm. It is only in our ‘hours-off,’ only in our moments of permitted festivity, that we find an analogy. Dance and game are frivolous, unimportant down here; for ‘down here’ is not their natural place. Here, they are a moment’s rest from the life we were placed here to live. But in this world everything is upside down. That which, if it could be prolonged here, would be a truancy, is likest that which in a better country is the End of ends. Joy is the serious business of Heaven’. – CS Lewis, Prayer: Letters to Malcolm (London: Collins, 1977), 94–5.

‘God’s loving is concerned with a seeking and creation of fellowship without any reference to an existing aptitude or worthiness on the part of the loved. God’s love is not merely not conditioned by any reciprocity of love. It is also not conditioned by any worthiness to be loved on the part of the loved, by any existing capacity for union or fellowship on his side … The love of God always throws a bridge over a crevasse. It is always the light shining out of darkness. In His revelation it seeks and creates fellowship where there is no fellowship and no capacity for it, where the situation concerns a being which is quite different from God, a creature and therefore alien, a sinful creature and therefore hostile. It is this alien and hostile other that God loves … This does not mean that we can call the love of God a blind love. But what He sees when He loves is that which is altogether distinct from Himself, and as such lost in itself, and without Him abandoned to death. That He throws a bridge out from Himself to this abandoned one, that He is light in the darkness, is the miracle of the almighty love of God’. – Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics II.1 (ed. G.W. Bromiley and T.F. Torrance; trans. T.H.L. Parker, et al.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1957), 278.

Here’s how I concluded:

If these two parables teach us anything at all about repentance, it is that the whole of our life is ‘finally and forever out of our hands and that if we ever live again, our life will be entirely the gift of some gracious other’ [Robert Farrar Capon, The Parables of Grace, 39]. The Gospel is the announcement that God finds us not in the garden of improvement but in the desert of death. It’s precisely from death that we are brought home. And these parables are about coming home. They speak to us about the nature of lostness, and about the necessity of experiencing lostness if we are to experience homecoming. ‘Weary or bitter or bewildered as we may be, God is faithful, He lets us wander so we will know what it means to come home’ [Marilynne Robinson, Home, 102]. So they teach us something about the nature of God.

They also give us a hint … of what history is about: that history is the time that God creates in order to find and to restore the lost. And, finally, these parables give us a hint about how that time will end, offering us every hope to believe that our stories do not end at the grave. Even hell is no obstacle, for this is a God who, in Jesus Christ, comes not only into the far country in search of us, but who also descends into the very depths of hell in order to carry us home. This is the God of relentless grace – the Hound of Heaven – and it is he and not death or any human decision who will decide how history ends. This is what it means to call God the judge of the living and the dead. Like the good shepherd in Ezekiel 34 who searches for the lost and rescues them from all the places where they are scattered, Jesus’ work is not done until all come home. He keeps seeking the lost, even in the grave. He seeks those who have refused his love. He seeks those who have abandoned his love. He seeks those who have never known of his love. He seeks those for whom life has ended prematurely. In Christ, there is no such thing as empty time, or ‘dead’ time, for all time is filled with Christ’s lordship over the living and the dead, and filled with experience of the Spirit who is the giver of life …

And here in Luke 15 we are given a picture of the nature of God, an insight into the purpose of history, and, I believe, a glimpse of how history ends, of how your life ends and my life ends – of how the lives of those we love and of those who have made life hell for us, will end – with celebration, with a banquet, with the extravagant joy with which God welcomes the found and eats with them, … with homecoming.

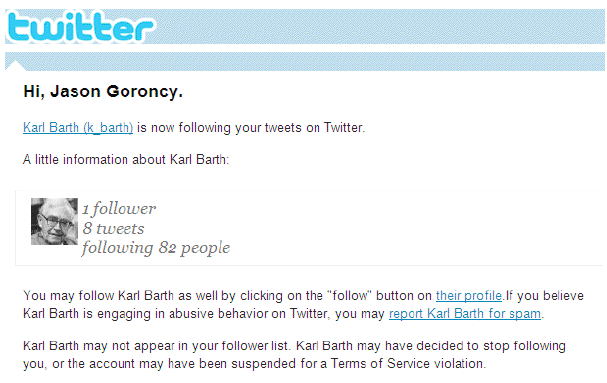

Karl Barth on Twitter

Now here’s an email I don’t get every day:

He walks with me and tweets with me

Along life’s narrow way.

He lives, He lives, Salvation to impart!

If you’re interested in following Uncle Karl, you can find him here.

Barth on the being and knowledge of God

Who was it that said recently that a day without reading something from Uncle Karl is a day wasted, or something to that effect? Well today, a friend of mine reminded me of this interesting passage (not least in light of the fruitful discussion that arose from my post on Ten (Draft) Propositions on the Missionary Nature of the Church) from Uncle Karl (CD §28), who, at least on my reading, properly refuses to collapse epistemology and ontology:

Who was it that said recently that a day without reading something from Uncle Karl is a day wasted, or something to that effect? Well today, a friend of mine reminded me of this interesting passage (not least in light of the fruitful discussion that arose from my post on Ten (Draft) Propositions on the Missionary Nature of the Church) from Uncle Karl (CD §28), who, at least on my reading, properly refuses to collapse epistemology and ontology:

‘When we ask questions about God’s being, we cannot in fact leave the sphere of His action and working as it is revealed to us in His Word. God is who He is in His works. He is the same even in Himself, even before and after and over His works, and without them. They are bound to Him, but He is not bound to them. They are nothing without Him. But He is who He is without them. He is not, therefore, who He is only in His works. Yet in Himself He is not another than He is in His works. In the light of what He is in His works it is no longer an open question what He is in Himself. In Himself He cannot, perhaps, be someone or something quite other, or perhaps nothing at all. But in His works He is Himself revealed as the One He is. It is, therefore, right that in the development and explanation of the statement that God is we have always to keep exclusively to His works (as they come to pass, or become visible as such in the act of revelation)—not only because we cannot elsewhere understand God and who God is, but also because, even if we could understand Him elsewhere, we should understand Him only as the One He is in His works, because He is this One and no other. We can and must ask about the being of God because as the Subject of His works God is so decisively characteristic for their nature and understanding that without this Subject they would be something quite different from what they are in accordance with God’s Word, and on the basis of the Word of God we can necessarily recognise and understand them only together with this their Subject.

At the same time we must be quite clear on the other side, that our subject is God and not being, or being only as the being of God. In connexion with the being of God that is here in question, we are not concerned with a concept of being that is common, neutral and free to choose, but with one which is from the first filled out in a quite definite way. And this concretion cannot take place arbitrarily, but only from the Word of God, as it has already occurred and has been given to us in the Word of God. This means that we cannot discern the being of God in any other way than by looking where God Himself gives us Himself to see, and therefore by looking at His works, at this relation and attitude—in the confidence that in these His works we do not have to do with any others, but with His works and therefore with God Himself, with His being as God.

What does it mean to say that “God is”? What or who “is” God? If we want to answer this question legitimately and thoughtfully, we cannot for a moment turn our thoughts anywhere else than to God’s act in His revelation. We cannot for a moment start from anywhere else than from there.

What God is as God, the divine individuality and characteristics, the essentia or “essence” of God, is something which we shall encounter either at the place where God deals with us as Lord and Saviour, or not at all. The act of revelation as such carries with it the fact that God has not withheld Himself from men as true being, but that He has given no less than Himself to men as the overcoming of their need, and light in their darkness—Himself as the Father in His own Son by the Holy Spirit. The act of God’s revelation also carries with it the fact that man, as a sinner who of himself can only take wrong roads, is called back from all his own attempts to answer the question of true being, and is bound to the answer to the question given by God Himself. And finally the act of God’s revelation carries with it the fact that by the Word of God in the Holy Spirit, with no other confidence but this unconquerable confidence, man allows being to the One in whom true being itself seeks and finds, and who meets him here as the source of his life, as comfort and command, as the power over him and over all things.

If we follow the path indicated, our first declaration must be the affirmation that in God’s revelation, which is the content of His Word, we have in fact to do with His act. And first, this means generally—with an event, with a happening. But as such this is an event which is in no sense to be transcended. It is not, therefore, an event which has merely happened and is now a past fact of history. God’s revelation is, of course, this as well. But it is also an event happening in the present, here and now. Again, it is not this in such a way that it exhausts itself in the momentary movement from the past to the present, that is, in our to-day. But it is also an event that took place once for all, and an accomplished fact. And it is also future—the event which lies completely and wholly in front of us, which has not yet happened, but which simply comes upon us. Again, this happens without detriment to its historical completeness and its full contemporaneity. On the contrary, it is in its historical completeness and its full contemporaneity that it is truly future. “Jesus Christ the same yesterday and to-day and for ever” (Heb. 13:8). This is something which cannot be transcended or surpassed or dispensed with. What is concerned is always the birth, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, always His justification of faith, always His lordship in the Church, always His coming again, and therefore Himself as our hope. We can only abandon revelation, and with it God’s Word, if we are to dispense with it. With it we stand, no, we move necessarily in the circle of its event or, in biblical terms, in the circle of the life of the people of Israel. And in this very event God is who He is. God is He who in this event is subject, predicate and object; the revealer, the act of revelation, the revealed; Father, Son and Holy Spirit. God is the Lord active in this event. We say “active” in this event, and therefore for our salvation and for His glory, but in any case active. Seeking and finding God in His revelation, we cannot escape the action of God for a God who is not active. This is not only because we ourselves cannot, but because there is no surpassing or bypassing at all of the divine action, because a transcendence of His action is nonsense. We are dealing with the being of God: but with regard to the being of God, the word “event” or “act” is final, and cannot be surpassed or compromised. To its very deepest depths God’s Godhead consists in the fact that it is an event—not any event, not events in general, but the event of His action, in which we have a share in God’s revelation.

The definition that we must use as a starting-point is that God’s being is life. Only the Living is God. Only the voice of the Living is God’s voice. Only the work of the Living is God’s work; only the worship and fellowship of the Living is God’s worship and fellowship. So, too, only the knowledge of the Living is knowledge of God’.

– Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics II.1 (ed. G.W. Bromiley and T.F. Torrance; trans. T.H.L. Parker, et al.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1957), 260–3.

So if you’ve read this far you can now sleep tonight in the full knowledge that your day wasn’t a complete waste of time. Certainy mine wasn’t: I drank gallons of Milo, finished marking a ute-load of assignments, and read some Barth. Oh, and we also decided on a school for our daughter, or at least I think we did!

‘The bodice of my new costume caught on the handlebar …’

- The Centre for Public Christianity (CPX) has posted two recent interviews with Paul Fiddes. And there’s more Fiddes here on ‘The End of the World: A Work in Progress’.

- Frank Rees posts on ‘Christian Freedom’ and a free church.

- John Pilger on why Tony Blair must be arrested.

- A public lecture by Professor Steve Reicher (professor of social psychology at the University of St Andrew’s) titled ‘Beyond the Banality of Evil’. The lecture, which goes for about 85 minutes, critically addresses Hannah Arendt’s hypothesis on the banality of evil arguing that those who commit extreme acts are not aware of the consequences of their actions; rather, they celebrate these consequences as moral.

- Jim Gordon posts on R S Thomas, the Crucified God and the virtue of metaphysical humility.

- Rick Floyd posts on Disability and Grace.

- Kimlyn J. Bender reviews Gunton’s The Barth Lectures. My own review of Gunton’s volume can be read here.

- Sung-Sup Kim reviews David Gibson’s Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth. My own review of this is here.

- Ben Myers, aka Mr Tomato Plant, shares two chapters of his forthcoming Man Booker Prize-shortlisted novel on gelato and the girl who buttons her coat as her ‘dad arrives to close the shop’.

- Here’s two books I’m waiting for: The Pastor: A Memoir by Eugene H. Peterson, and Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom by Peter J. Leithart

- Finally, I’m enjoying U2’s Go Home: Live from Slane Castle.

Around: ‘Love seeketh not itself to please’

- Stanley Hauerwas and the university

- Richard Hays on the word of reconciliation

- Byron Smith shares a great quote from Karl Rahner on ‘Christian pessimism’

- John Pilger on ‘Julia Gillard, the new warlord of Oz’

- Walter Kasper on the regret of no shared communion

- Elliott Prasse-Freeman on Retaking power in Burma (Part I)

- Carol Howard Merritt on What Causes Pastors to Burnout?

- J.R. Daniel Kirk shares a parents prayer

- Kim Fabricius shares a wonderful sermon on baptism

- Sung-Sup Kim reviews David Gibson’s Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth

- Ben Myers is completely uninterested in ‘being a real man’

- ‘Speaking Christian: A Commencement Address for Eastern Mennonite Seminary’ by Stanley Hauerwas

- Finally, here’s some William Blake that I’m enjoying today:

‘The Clod and the Pebble’

‘Love seeketh not itself to please,

Nor for itself hath any care,

But for another gives its ease,

And builds a heaven in hell’s despair.’

So sung a little clod of clay,

Trodden with the cattle’s feet,

But a pebble of the brook

Warbled out these metres meet:

‘Love seeketh only Self to please,

To bind another to its delight,

Joys in another’s loss of ease,

And builds a hell in heaven’s despite.’

Lectures by T.F. Torrance, Interview with Trevor Hart

Grace Communion International have made available for download T.F. Torrance’s lectures on the Ground And Grammar Of Theology. These were given in 1981 at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Grace Communion International have made available for download T.F. Torrance’s lectures on the Ground And Grammar Of Theology. These were given in 1981 at Fuller Theological Seminary.

- Lecture 1

- Lecture 2

- Lecture 2 Q&A

- Lecture 3

- Lecture 3 Q&A

- Lecture 4

- Lecture 4 Q&A

- Lecture 5

- Lecture 5 Q&A

- Lecture 6

- Lecture 6 Q&A

- Lecture 7

- Lecture 7 Q&A

- Lecture 8

- Lecture 8 Q&A

- Lecture 9

- Lecture 9 Q&A

- Lecture 10

- Lecture 10 Q&A

They have also uploaded a recent interview with Dr. Trevor Hart, in which Trevor (who was my Doktorvater) talks with characteristic clarity about the theology of Karl Barth, and about the vicarious humanity of Jesus Christ.

They have also uploaded a recent interview with Dr. Trevor Hart, in which Trevor (who was my Doktorvater) talks with characteristic clarity about the theology of Karl Barth, and about the vicarious humanity of Jesus Christ.

You can watch the interview here.

Reading Genesis 1:2

A guest post by Rev. Dr John Emory McKenna. [John, a student of TF Torrance, serves as a Doctrinal Advisor to the Worldwide Church of God in California, as Professor & Vice-President at the World Mission University in Los Angeles, and as Adjunct Professor with Haggard Graduate School of Theology. He has published The Setting in Life for The Arbiter of John Philoponus, 6th Century Alexandrian Scientist and The Great AMEN of the Great I-AM: God in Covenant with His People in His Creation]

A guest post by Rev. Dr John Emory McKenna. [John, a student of TF Torrance, serves as a Doctrinal Advisor to the Worldwide Church of God in California, as Professor & Vice-President at the World Mission University in Los Angeles, and as Adjunct Professor with Haggard Graduate School of Theology. He has published The Setting in Life for The Arbiter of John Philoponus, 6th Century Alexandrian Scientist and The Great AMEN of the Great I-AM: God in Covenant with His People in His Creation]

About Genesis 1:2, Karl Barth has written, “This verse has always constituted a particular crux interpretum – one of the most difficult in the whole Bible – and it is no small comfort to learn from Gunkel that it is a ‘veritable mythological treasure chamber.’”[1] After a rather thorough examination and analysis of the history of the exegesis this verse, the great Swiss theologian concluded in a fine print section of his reading, “Our only option is to consider v.2 as a portrait, deliberately taken from myth, as the world which according to His revelation was negated, rejected, ignored and left behind in His actual creation.”[2] Barth develops his understanding of ‘Das Nichtige’ (‘The Nothingness’), as belonging to the mystery of evil in the Biblical world, a world he reminds us that is very different from the one with which we are already only too familiar. The ‘chaos (תהו) and emptiness (בהו), ‘darkness’ (חשך) and ‘deep’ (תהום) of the ‘waters’ (מים) over which the Spirit of God ‘broods’ (מרחפת) in Genesis 1:2 are terms, then, that belong to the myths and idols of those views of the world that exists outside of God’s Revelation of His ‘Very Good’ Creation. Genesis 1:2 belongs to a confession, in common with the various ‘creation epics’ found among the nations of the Ancient Near East, that contradicts the perfection inherent to the Creation Week according Israel’s view of the world.[3]

In this post, I will argue that Barth’s understanding of the significance of Genesis 1:2 and his assertion that ‘Das Nichtige’ of Israel’s Creation Theory is only a partial grasp of the intent and purpose of the author of the confession of the Creation Week. I would argue that Barth’s grasp of the meaning of Genesis 1:2, achieved in the context of a general consensus accomplished by modern or post-modern methods of historical-critical methods of interpretation applied to Genesis, is only a partial understanding of the purpose of the significance of the confession. I will argue that, for suppositional reasons, the modern mind has become more comfortable with reading the creation out of chaos of v. 2 as the intent of the confession, when we tend to disregard the implication of doctrine of creatio ex nihilo found within the Judeo-Christian tradition of interpretation.[4] The willingness to divorce our understanding of chaos, emptiness, darkness, and the deep of the waters, over which the Spirit of God is said to ‘brood’, is the willingness of modern Biblical Theologians to remain separated from the meaning of the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo of v. 1, a meaning with which the early fathers of the Church steadily wrestled.[5] We will argue that the preference for reading the concept of ‘creation out of something’, without a confession of the ‘creation out of nothing’ doctrine, perpetuates a fragmentation in our understanding of the meaning of ‘Day One’ in the Creation Week inherent in the confession of Israel’s Moses, the great prophet of her history among the nations. We need to recover the interpretation of the early fathers of the Church and obtain a fresh grasp of the theological wholeness of the confession in our time our theology and its relationship with science.

The confession of the Creation Week possesses, from beginning to end, a wholeness the polemical power of which is purposed to call Israel among the nations in God’s Creation away from her idols and myths about the gods and the world. It posits a background whereby the other creation epics prevalent in the Ancient Near East are denied their claims to the reality of the world, of mankind, and of God. It would transform any language into that service that is true to the intention and purpose of the Voice Moses heard in the Burning Bush and in the events of the Exodus of Israel from Egypt. ‘The Beginning’ according to Moses’ claims that no other Voice than this Voice is to heard as the Creator of the world and its mankind. Against all the idol and myth-making among the nations surrounding Israel in the ANE, Israel as the People of God must bear witness to this One, who as the Creator is the Great I-AM and Lord of the world’s redemption. In the face of Moses’ witness as the Prophet in the Ancient World, mankind is to throw away its myths and idols about the world of the gods. This One is the Redeemer-Creator who as the Great I-AM would be known as the One He truly is, the Creator of ‘the Beginning’ in the Beginning.

Genesis 1:2 may not be construed as possessing, in common with the creation epics found and read among the nations in the ANE, a language influenced in its significance by the myths and gods of the ancient peoples, but a language meant to transform their beliefs into the real service of the Revelation that drove Moses to his confession. We will claim that, just as the Exodus of Israel is something new in the history of the world, Moses’ confession of the Creator, based upon the Revelation with him of the Redeemer, is something new in the history of the race’s understanding of the Creation and the Creator. The One of this Revelation is to be known as the true Creator of the heavens and the earth. The One of this Revelation, the Redeemer of Israel among the nations in His Creation, is to be known against the myths of the gods of the ancient peoples. This One is the True Creator who possesses nothing in common with the gods of the ancient worlds, with their cosmogonies, with their interactions with our kind, with the idol-making common to the times. Rather, with this One the reality of the world as God’s Creation is to known in its nature, free from the magic and the superstitions of these peoples. This is the One who is Israel’s Lord and God, the One who redemptive acts with Israel would have His People to know their true Creator. With His acts to deliver Israel from her bondage to Egyptian gods and Egypt’s Pharaoh, wrought through the priestly and prophetic servant of God Moses was called to be, Israel is commanded to understand and to throw away all her gods, her Mesopotamian gods, her Egyptian gods, her Canaanite gods, and so forth, and know Him as the Great I-AM He is. When Moses employs, then, the terms of his confession among the nations in the ancient world, he would transform their meaning and give them a new significance never before heard in the history of the world. We do well, I believe, to hear them on his terms and not our own.

The language of Moses’ confession, then, transforms the terms that may be found in common among the peoples of the nations in the ancient world into meaning that serves the Voice of God in His Beginning of the heavens and the earth and so forth. The Voice that spoke with him from the flames of the Burning Bush at Horeb is the Voice that speaks in the Creation Week. The events of the Exodus of Israel from Egypt all belong to this Voice. This is the Voice Moses learns to confess as the Creator with His Creation. To Israel with this Voice is given the knowledge that her Redeemer is none other than the Creator of the Creation. Moses’ confession is purposed to serve this Voice with an intention that belongs to the redemption of Israel in the Exodus and the knowledge of her Lord and God, the Creator of the Beginning. This is the One Lord God Israel must hear and follow. This is the Voice of the Great I-AM the One Lord God is. This is the Creator of the holy ground on which Moses stands at Horeb and on which Israel must always stand. This is the Creator. His Beginning is the Beginning confessed against all idols and idol-making about the gods of the world. This is the Lord God of space, time, and all things that exist as created realities. The power of Moses’ polemic ought never be allowed to escape our attention. It belongs to what is universal. It belongs to what is particular. It belongs to what mankind is under the heavens and upon the earth as rooted in this Self-Revelation of the Great I-AM the Lord God is with Moses, His Servant. The confession of the formation of ‘Day One’ of the Creation Week belongs to this Revelation. It is with this Beginning that Moses knows the ‘Very Good’ orders of the Creation Week, blessed by God. It is in the light of the Great I-AM the Redeemer is with His People among the nations that Israel can confess the Creator and His Creation.[6]