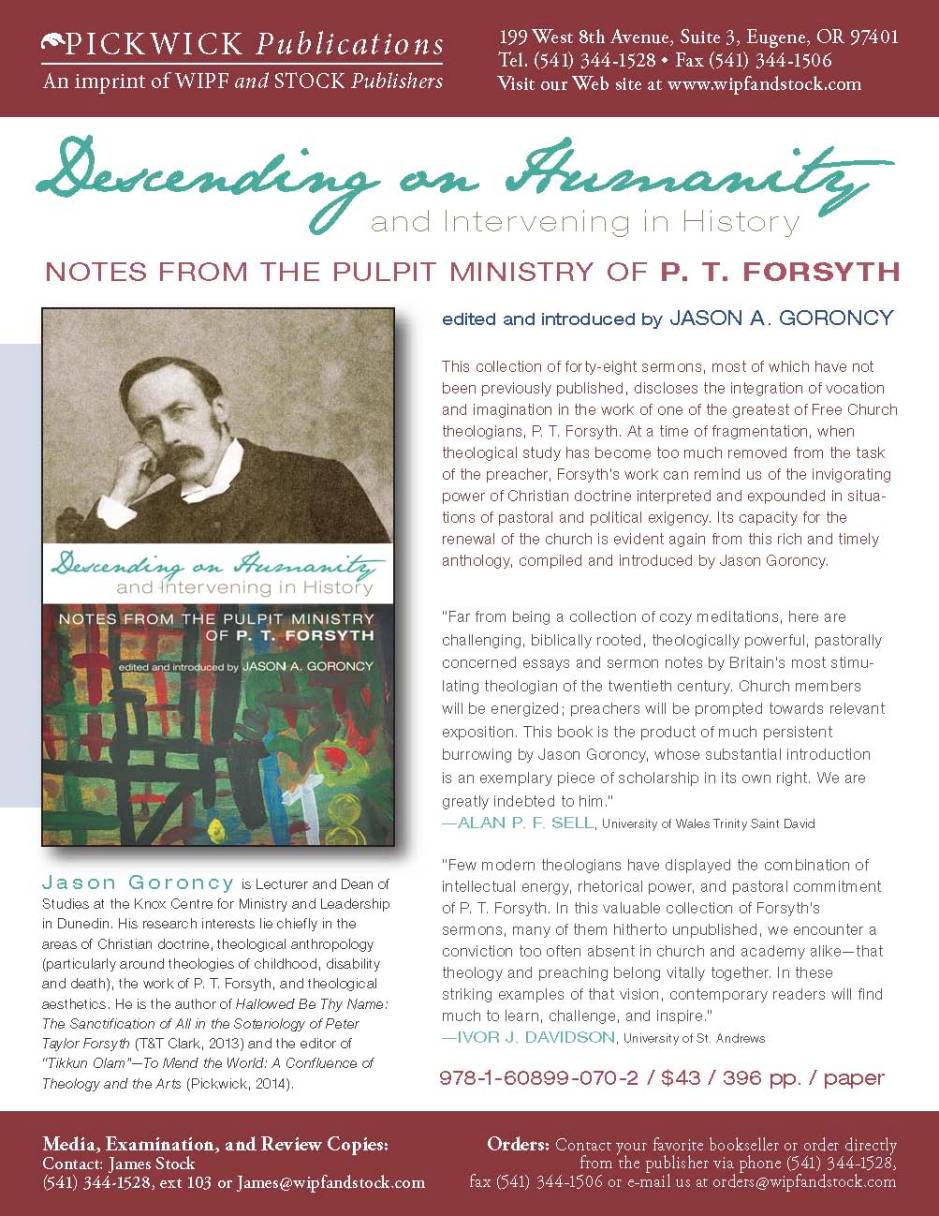

I am delighted to announce that my latest edited volume – Tikkun Olam—To Mend the World: A Confluence of Theology and the Arts – is now available. It has received kind endorsements from Jeremy Begbie and Paul Fiddes, and the Table of Contents reads:

I am delighted to announce that my latest edited volume – Tikkun Olam—To Mend the World: A Confluence of Theology and the Arts – is now available. It has received kind endorsements from Jeremy Begbie and Paul Fiddes, and the Table of Contents reads:

Foreword: Alfonse Borysewicz

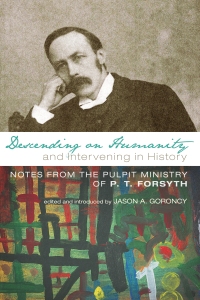

Introduction: Jason Goroncy

1. “Prophesy to these Dry Bones”: The Artist’s Role in Healing the Earth — William Dyrness

2. Cosmos, Kenosis, and Creativity — Trevor Hart

3. Re-forming Beauty: Can Theological Sense Accommodate Aesthetic Sensibility? — Carolyn Kelly

4. Questioning the Extravagance of Beauty in a World of Poverty — Jonathan Ryan

5. Living Close to the Wound — Libby Byrne

6. The Sudden Imperative and Not the Male Gaze: Reconciliatory Relocations in the Art Practice of Allie Eagle — Joanna Osborne and Allie Eagle

7. Building from the Rubble: Architecture, Memory, and Hope — Murray Rae

8. The Interesting Case of Heaney, the Critic, and the Incarnation — John Dennison

9. New Media Art Practice: A Challenge and Resource for Multimedia Worship — Julanne Clarke-Morris

10. Silence, Song, and the Sounding-Together of Creation — Steven Guthrie

A brief section from the Introduction provides a summary of each chapter:

The essays compiled in this volume, each in their own way, seek to attend to the lives and burdens and hopes that characterize human life in a world broken but unforgotten, in travail but moving toward the freedom promised by a faithful Creator. Bill Dyrness’s essay focuses on the way that the medieval preference for fiction over history has been exactly reversed in the modern period so that we moderns struggle to make a story out of the multitude of facts. Employing Augustine’s notion of signs as those which move the affections, the chapter develops the notion of poetics as the spaces in peoples’ lives that allow them to keep living and hoping, suggesting one critical role that art can play in imagining another world, a better world. For art offers to carry us to another place, one that doesn’t yet exist, and in this way offers hope and sustenance to carry people through the darkest times. This is illustrated by the outpouring of Haiku after the recent tsunami in Japan, or in the spaces made available for poetry in Iraq. Most importantly, it is underwritten by the centrality of lament in the biblical materials wherein we are reminded that lament and prophecy provide aesthetic forms that carry believers toward the future that God has planned for the world.

The essay by Trevor Hart considers the place of human “creativity” (artistic and other sorts) and seeks to situate it in relation to God’s unique role as the Creator of the cosmos. It draws on literary texts by Dorothy Sayers and J. R. R. Tolkien, as well as theological currents from Jewish writers and Christian theologians, to offer a vision of human artistry as (in Tolkien’s preferred phrase) “sub-creation,” a responsible participation in a creative project divinely initiated, ordered, and underwritten, but left deliberately unfinished in order to solicit our active involvement and ownership of the outcomes.

Beauty, Hans Urs von Balthasar has suggested, is “a word from which religion, and theology in particular, have taken their leave and distanced themselves in modern times by a vigorous drawing of boundaries.” More recently, a number of theologians have addressed this distance and attempted to dismantle the boundaries widely assumed between certain Protestant theologies and the realm of the arts or aesthetics. In her essay, Carolyn Kelly seeks to contribute to that communal exploration by addressing the particularly imposing boundary line demarcating, on the one hand, Reformed affirmations of the beauty of Truth and, on the other, a Romantic commitment to the truth of Beauty. Kelly reflects on what Romantic and aesthetic “sensibility” might gain from its modern counterpart and, in turn, what Reformed theological “sense” might have to gain from a re-cognition of Beauty.

But what place is there for extravagant works of beauty in a world tarnished with the ugliness of poverty and injustice? This is a question taken up by Jonathan Ryan in his essay. Beginning with the recollection of the disciples’ objection to an extravagant act of beauty retold in Mark 14:4, Ryan allows the “anointing at Bethany” narrative in Mark 14 to frame this question and to suggest the legitimacy—and necessity—of works of beauty and creativity for bearing witness to God’s extravagant love for the world.

Libby Byrne’s essay explores the premise that the artist’s calling is to “live close to the wound.” Locating this contention within the nexus that seems to exist between art, theology and philosophy, she argues that we are able to consider the prevailing conditions required for the artist to work toward the task of mending that which is broken, and, drawing on theory from Matthew Del Nevo and Rowan Williams, Byrne helps us understand the importance of melancholy and vulnerability in the sacramental work of human making. She provides examples of how this theory may work in practice with particular reference to the work of Anselm Kiefer and finally with her own studio practice, reminding us that it takes courage to choose to live and work close to our wounds, and also that by so doing the artist not only opens themselves to the possibility of transformation but also offers to others gifts that reverberate within the world and that call us to healing and wholeness.

New Zealand artists Allie Eagle and Joanna Osborne discuss the Sudden Imperative, Eagle’s art project that reframes much of the ideology she held as a feminist separatist during the 1970s. They also outline a reappraisal of direction and motivation in Eagle’s thinking and highlight the theological and reconciliatory center of her current art practice.

Murray Rae takes up the question posed by Theodor Adorno following the Jewish Holocaust and considers whether art can have anything at all to say in the face of evil or whether some evils might, in fact, be unspeakable. Through a consideration of architecture and, in particular, the work of Daniel Libeskind at Ground Zero and in the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Rae contends that while architecture, along with the arts more generally, has no power to redeem us, much less to make amends, it can nevertheless give expression to our memories, our sorrow, and our penitence. He concludes that art may also reveal the extent to which the Spirit is at work within us, prompting us toward forgiveness and reconciliation and a true mending of the world.

In his essay on the Irish poet Seamus Heaney, John Dennison argues that one of the most notable—and least understood—aspects of Heaney’s trust in the good of poetry and the arts in general is the way in which his account approximates religious faith. Some critics have been encouraged toward the conclusion that Heaney’s poetics constitutes an active (if heterodox and often apophatic) extension of Christian theology through the arts. Most importantly here, John Desmond in his book Gravity and Grace argues that Heaney’s writings assume certain fundamentals that mark his transcendental cultural poetics as Christian. Central to Heaney’s thought, Desmond insists, is the doctrine of the Incarnation. Christian doctrine, and in particular the doctrine of the Incarnation, is indeed central to understanding the character of Heaney’s public commitment to the restorative function of art. But, Dennison argues, if we attend to the development and structures of Heaney’s thought, we can see how this influential account of the arts’ world-mending powers is not so much extensive with Christian soteriology as finally delimited by the biblical and theological descriptions it knowingly appropriates. It allows us to see, also, the degree to which Heaney’s trust in the adequacy of poetry turns on a refracted after-image of Christian doctrine, particularly that of the Incarnation.

Julanne Clarke-Morris’s offering proposes that multimedia worship and worship installations would benefit from a more consistent approach to aesthetics and context than is often the norm. She suggests that new media art forms offer communities of faith a range of ready-made critical practices that could amiably be brought to bear in the case of liturgical installation art. Seeking to draw attention to the coherence and communicative power of multimedia liturgical installations in order to improve both their accessibility and artistic credibility, she investigates some significant insights from virtual reality art, immersion art, multimedia installation art, and site-specific art as resources for preparing worship installations and assessing their effectiveness.

The closing essay, penned by Steven Guthrie, bears witness to ways in which Christian scripture and the Christian theological tradition both testify to a natural world that has a voice; one that not only speaks, but sings. The Hebrew prophet Isaiah speaks of mountains and hills “bursting forth in song” (Isaiah 55), and St John exiled on the island of Patmos listens with astonishment to “every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth” singing (Revelation 5). This idea is taken up in turn by Augustine, Boethius and many others in the tradition, where it is often joined to the Pythagorean idea of “the music of the spheres.” According to this tradition, all of creation comprises a finely tuned symphony, the combined voices of which articulate the Creator’s praise. This tradition of thought—conceiving of the world as a singing creation—is a valuable resource for all who hope to faithfully care for God’s world. The musical creation described by Augustine and other theologians is a beautiful and profoundly interconnected cosmos, filled with an astonishing harmony of human and non-human voices. In this universal song, humans have a vital but circumscribed role. Silence, song and harmony have the capacity to make us more—or less—fully aware of, and more—or less—responsive to the world we inhabit. Music may act as a kind of aural armor by which we shut out the voices of the creation and others who inhabit it. It may also be a weapon by which we dominate the surrounding space. Or music may be a schoolmaster from whom we learn attentiveness and responsiveness, and with which we might join with all creation to participate in God’s symphonic work of healing the creation.

More information about the book is available here.