- Keith Thomas laments the state of the modern university, in Universities under Attack.

- Charles Simic on Serenity.

- Alan Hollinghurst and Jeffrey Eugenides on the art of fiction.

- The Changi POW artwork of Des Bettany is finally online – a beautiful project. Speaking of war art, check out Macy Halford’s piece on An Artist’s War.

- Chad Marshall reviews Mark S. Gignilliat’s Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel: Barth’s Theological Exegesis of Isaiah.

- Michiko Kakutani reviews Robert Hughes’s Rome: A Cultural, Visual, and Personal History.

- Jarrod M. Longbons’s interview with Tracey Rowland on Pope Benedict XVI.

- The gospel according to Stephen Fry; and Fry on London.

- The Centre for Theology and Ministry (Uniting Church in Australia) is seeking a new Professor of Systematic Theology.

- Robert Fisk on bankers as the dictators of the West.

- Ben Myers looks through an icon of theophany.

- Rick Floyd reminds me of that old Bing Crosby cassette I probably still have laying around in a box somewhere.

- A Rowan Williams lecture on The Future of Interfaith Dialogue.

- Crispin Blunt’s lecture on Restorative Justice.

- Steve Holmes reviews Scot McKnight’s Junia Is Not Alone.

- Finally, I’m still relishing John Updike’s Higher Gossip.

Art

Human artistry and the adding of value to creation

While preparing some lectures recently on theology and the arts, I was struck again by one limitation that both art and Christian theology share – namely, the impossibility of absolute innovation. As Rowan Williams noted, ‘To add to the world, to extend the world and its possibilities, the artist [like the theologian] has no option but to take his [or her] material from the world as it is’. Even our best attempts at liberation from words, from the determinations of human language and imaginings, can only carry us so far as we are brought to what Williams calls ‘a complete imaginative void, the dark night of an utter alienation from the “available” world, “the desert of the heart”’.

While preparing some lectures recently on theology and the arts, I was struck again by one limitation that both art and Christian theology share – namely, the impossibility of absolute innovation. As Rowan Williams noted, ‘To add to the world, to extend the world and its possibilities, the artist [like the theologian] has no option but to take his [or her] material from the world as it is’. Even our best attempts at liberation from words, from the determinations of human language and imaginings, can only carry us so far as we are brought to what Williams calls ‘a complete imaginative void, the dark night of an utter alienation from the “available” world, “the desert of the heart”’.

Still, the human response of taking up ‘material from the world as it is’ does not obviate the truth that the world is God’s, nor suggest that God ‘“made something” and then wondered what to do with it’. Rather, as Ruth Etchells puts it in A Model of Making: Literary Criticism and its Theology, ‘from the first the creative purpose was one of profound and secure relationship’. And, it seems, if such a relationship is to be truly characterised by love, then its prime instigator will also create ‘room’ for creation to be itself. In other words, God’s love achieves its end not through brute force but by patient regard for what Emmanuel Levinas termed the ‘otherness of the other’. To be sure, God never retreats from creation into some kind of self-imposed impotence, but rather remains unswervingly faithful, interested and involved in all that goes on. But this is not to suggest that all is, so to speak, in order. And so Christians, when they speak of creation, will want to speak, as many physicists too will want to do, not only of creation’s order and but also of its disorder, not only about its being but also about its becoming, and about the space that God has granted the world, space which implies some risk, and which can neither be ignored nor annihilated if all there is is to be brought to love telos; i.e., to all that ‘God has prepared for those who love him’ (1 Cor 2.9).

Not a few scholars and practitioners are now talking about the sense in which art serves to make this space meaningful, and of the way that art is concerned to transform created things, to improve creation, to add value to creation, to, in Auden’s words, ‘make a vineyard of the curse’. J.R.R Tolkien understood this well, as his fairy stories and indeed his entire project of mythopoesis attest his concern to not merely ennoble, challenge and inspire, but also to heighten reality itself, to invite us to look again at familiar things, and see them as if for the first time. Jacques Maritain, too, in Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry, once wrote that ‘Things are not only what they are. They ceaselessly pass beyond themselves, and give more than they have …’. In other words, it is claimed that there is absolutely nothing passive going on when a painter picks up a piece of charcoal, or a dancer performs Swan Lake. Abraham Kuyper was right to insist in his 1898 Stone lectures that art ‘discover[s] in those natural forms the order of the beautiful, and … produce[s] a beautiful world that transcends the beautiful of nature’. And others, too, have spoken of the way that the arts contribute to the transformation of disorder, bearing witness to the belief that creation is not indispensable to God’s liberating purposes for all that God has made, purposes which point not to a return to a paradise lost but to a creation made new, a making new which apprehends the reality of human artistry and which proceeds in the hope that both the location and the vocation of the children of God is inseparable from creation itself.

Alfonse Borysewicz on his art

For regular readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem, the name of New York-based artist Alfonse Borysewicz will be somewhat familiar. While on a trip recently to the USA, I had the privilege and joy of staying with Alfonse and his family, during which time my appreciation of his work and its importance at this moment in history was more-deeply confirmed. (I was almost-equally impressed with the intimate knowledge he had of, and affection he displayed about, NYC’s subway system). Alfonse’s bookshelves betray a mind that has long-wrestled with theology, philosophy and aesthetics. But like most artists, Alfonse is more comfortable speaking into and through his art than he is speaking about his art. Still, he does a good deal of, and good job with, the latter too. Here he is in a recent interview produced by Calvary Baptist Church in Grand Rapids:

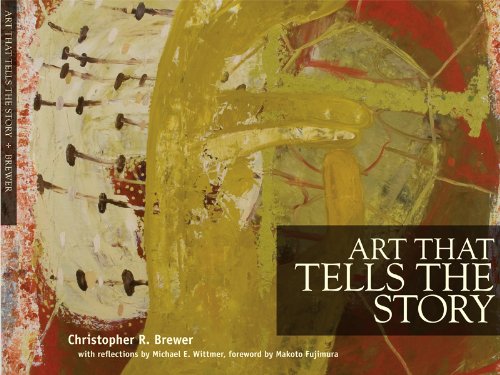

Art that Tells the Story: a commendation

We homo sapiens are, essentially, both a storied people and a story-telling people. So, a basic human question is not primarily, ‘What am I, as an individual, to do or decide?’ but rather, ‘Of what stories do I find myself a part, and thus who should I be?’; for we literally live by stories. The Church, too, understands itself as a pilgrim people, as a people storied on the way, as a people whose very way becomes the material which shapes the narrative that has long preceded it and which is being written with it. It understands that being human never begins with a white piece of paper. As Alasdair MacIntyre rightly reminds us in After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, we never start anywhere. Rather, we simply find ourselves within a story that has been going on long before our arrival and will continue long after our departure. Moreover, Christian community begins with being found in the very act of God’s self-disclosure, an act which, in Jamie Smith’s words, ‘cuts against the grain of myths of progress and chronological snobbery’ and places us in the grain of the universe. And what – or, more properly, who – is disclosed in that crisis of discovery is one who provides memory, unity, identity and meaning to the story of our life. So Eberhard Jüngel: ‘We are not … simply agents; we are not just the authors of our biography. We are also those who are acted upon; we are also a text written by the hand of another’. Hence it is not just any story by which the Church lives but rather a particular story given to it – namely, Israel’s story in which, in the words of R.S. Thomas, it ‘gaspingly … partake[s] of a shifting identity never [its] own’.

We homo sapiens are, essentially, both a storied people and a story-telling people. So, a basic human question is not primarily, ‘What am I, as an individual, to do or decide?’ but rather, ‘Of what stories do I find myself a part, and thus who should I be?’; for we literally live by stories. The Church, too, understands itself as a pilgrim people, as a people storied on the way, as a people whose very way becomes the material which shapes the narrative that has long preceded it and which is being written with it. It understands that being human never begins with a white piece of paper. As Alasdair MacIntyre rightly reminds us in After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, we never start anywhere. Rather, we simply find ourselves within a story that has been going on long before our arrival and will continue long after our departure. Moreover, Christian community begins with being found in the very act of God’s self-disclosure, an act which, in Jamie Smith’s words, ‘cuts against the grain of myths of progress and chronological snobbery’ and places us in the grain of the universe. And what – or, more properly, who – is disclosed in that crisis of discovery is one who provides memory, unity, identity and meaning to the story of our life. So Eberhard Jüngel: ‘We are not … simply agents; we are not just the authors of our biography. We are also those who are acted upon; we are also a text written by the hand of another’. Hence it is not just any story by which the Church lives but rather a particular story given to it – namely, Israel’s story in which, in the words of R.S. Thomas, it ‘gaspingly … partake[s] of a shifting identity never [its] own’.

Back in 1993, Robert Jenson wrote a great little piece titled ‘How the World Lost Its Story’ (First Things 36 (1993), 19–24). He opened that essay with these words:

Back in 1993, Robert Jenson wrote a great little piece titled ‘How the World Lost Its Story’ (First Things 36 (1993), 19–24). He opened that essay with these words:

It is the whole mission of the church to speak the gospel … It is the church’s constitutive task to tell the biblical narrative to the world in proclamation and to God in worship, and to do so in a fashion appropriate to the content of that narrative, that is, as a promise claimed from God and proclaimed to the world. It is the church’s mission to tell all who will listen, God included, that the God of Israel has raised his servant Jesus from the dead, and to unpack the soteriological and doxological import of that fact.

To speak the gospel and, in Jenson’s parlance, to ‘do so in a fashion appropriate to the content of that narrative’, the Church is given a pulpit, a font and a table; in fact, many pulpits, fonts and tables. And these remain the principle ‘places’ where the people of God can expect to hear and to see and to taste and to learn and to proclaim the story into which they have been gathered, redeemed and made an indispensable character. This is not, however, to suggest that these are the only places wherefrom the free and sovereign Lord may speak, nor to aver in any way that the gospel is somehow kept alive by the Church’s attempt to be a story teller, for the story is itself nothing but God’s own free and ongoing history in Jesus. As Jüngel put it in God as the Mystery of the World, ‘God does not have stories, he is history’.  To speak gospel is literally to proclaim God, speech that would be a lie and completely empty were it not the story of God with us, of the saving history which has become part of God’s own narrative, of the world which has, in Jesus Christ, become ‘entangled in the story of the humanity of God’ (Jüngel), a story at core kerygmatic and missionary, and unfinished until all its recipients are included in its text. For, as Jenson has written in his much-too-neglected Story and Promise, the story of Jesus – who is the content of the gospel – ‘is the encompassing plot of all men’s stories; it promises the outcome of the entire human enterprise and of each man’s involvement in it’. To know this man’s story, therefore, is to know not only the story of God but also our own story. Indeed, it is the story that makes human life possible at all. As Jenson would write elsewhere, ‘Human life is possible — or in recent jargon “meaningful” — only if past and future are somehow bracketed, only if their disconnection is somehow transcended, only if our lives somehow cohere to make a story’.

To speak gospel is literally to proclaim God, speech that would be a lie and completely empty were it not the story of God with us, of the saving history which has become part of God’s own narrative, of the world which has, in Jesus Christ, become ‘entangled in the story of the humanity of God’ (Jüngel), a story at core kerygmatic and missionary, and unfinished until all its recipients are included in its text. For, as Jenson has written in his much-too-neglected Story and Promise, the story of Jesus – who is the content of the gospel – ‘is the encompassing plot of all men’s stories; it promises the outcome of the entire human enterprise and of each man’s involvement in it’. To know this man’s story, therefore, is to know not only the story of God but also our own story. Indeed, it is the story that makes human life possible at all. As Jenson would write elsewhere, ‘Human life is possible — or in recent jargon “meaningful” — only if past and future are somehow bracketed, only if their disconnection is somehow transcended, only if our lives somehow cohere to make a story’.

And here we come up against the perennial question of human speech, and it’s back to Jüngel (and to Peter Kline’s article on Jüngel and Jenson) to help me out: ‘The language which corresponds to the humanity of God’, writes Jüngel, ‘must be oriented in a highly temporal way in its language structure. This is the case in the language mode of narration, [or] telling a story’. In other words, if Kline reads Jüngel correctly, Jüngel is suggesting that narrative or story is the mode of human  language which most appropriately corresponds to the form of God’s life among and with us. Commenting on Jüngel, Kline argues that narrative alone witnesses to the change from old to new, can capture the movement and becoming in which God has his being, corresponds to the eschatological event of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and brings ‘the word of the cross’ to expression in a way apposite to us. So Jüngel: ‘God’s humanity introduces itself into the world as a story to be told’. Kline notes that for Jüngel, the church is given a story to tell, but, in Jüngel’s words, it ‘can correspond in [its] language to the humanity of God only by constantly telling the story anew’. God’s humanity ‘as a story which has happened does not cease being history which is happening now, because God remains the subject of his own story . . . God’s being remains a being which is coming’. The community, Kline says, tells only the story of Jesus Christ’s history, and so it constantly looks back to what has happened. Yet the telling of this story is also always new because God’s entrance into human language that once happened continues to happen again and again as Jesus Christ continues to live in the freedom of the Spirit. God is not confined to his once-enacted history, to one language or culture; history does not consume God. So Jüngel again: ‘God who is eschatologically active and who in his reliability is never old [is] always coming into language in a new way’.

language which most appropriately corresponds to the form of God’s life among and with us. Commenting on Jüngel, Kline argues that narrative alone witnesses to the change from old to new, can capture the movement and becoming in which God has his being, corresponds to the eschatological event of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and brings ‘the word of the cross’ to expression in a way apposite to us. So Jüngel: ‘God’s humanity introduces itself into the world as a story to be told’. Kline notes that for Jüngel, the church is given a story to tell, but, in Jüngel’s words, it ‘can correspond in [its] language to the humanity of God only by constantly telling the story anew’. God’s humanity ‘as a story which has happened does not cease being history which is happening now, because God remains the subject of his own story . . . God’s being remains a being which is coming’. The community, Kline says, tells only the story of Jesus Christ’s history, and so it constantly looks back to what has happened. Yet the telling of this story is also always new because God’s entrance into human language that once happened continues to happen again and again as Jesus Christ continues to live in the freedom of the Spirit. God is not confined to his once-enacted history, to one language or culture; history does not consume God. So Jüngel again: ‘God who is eschatologically active and who in his reliability is never old [is] always coming into language in a new way’.

‘Telling the story anew’. ‘God … [is] always coming into language in a new way’. Which brings me to Chris Brewer’s new book, Art that Tells the Story. Others have already summarised the book, so let me simply say that Art that Tells the Story is a freshly-presented and beautifully-produced book which attempts to tell the old, old story … again. Boasting some intriguing prose (by Michael E. Wittmer) and coupled with well-curated images from a diverse array of accomplished visual artists including Jim DeVries, Wayne Forte, Edward Knippers, Barbara Februar, Clay Enoch, Julie Quinn, Michael Buesking and Alfonse Borysewicz, among others, herein, word and image work in concert to open readers up to hear and see again, and to hear and see as if for the first time, the Bible’s story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, inviting – nay commanding!, for the gospel is command – readers to comprehend in this story their own, and to enter with joy into the narrative which is the life of all things. A book this beautiful ought to be in hardback; but may it, all the same, find itself opened and dialogued with next to many coffee mugs, and in good and diverse company. Like its subject, this is one to sit with, to be transformed by, and to share with others.

‘Telling the story anew’. ‘God … [is] always coming into language in a new way’. Which brings me to Chris Brewer’s new book, Art that Tells the Story. Others have already summarised the book, so let me simply say that Art that Tells the Story is a freshly-presented and beautifully-produced book which attempts to tell the old, old story … again. Boasting some intriguing prose (by Michael E. Wittmer) and coupled with well-curated images from a diverse array of accomplished visual artists including Jim DeVries, Wayne Forte, Edward Knippers, Barbara Februar, Clay Enoch, Julie Quinn, Michael Buesking and Alfonse Borysewicz, among others, herein, word and image work in concert to open readers up to hear and see again, and to hear and see as if for the first time, the Bible’s story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, inviting – nay commanding!, for the gospel is command – readers to comprehend in this story their own, and to enter with joy into the narrative which is the life of all things. A book this beautiful ought to be in hardback; but may it, all the same, find itself opened and dialogued with next to many coffee mugs, and in good and diverse company. Like its subject, this is one to sit with, to be transformed by, and to share with others.

Flannery O’Connor once confessed, in Mystery and Manners, that ‘there is a certain embarrassment about being a story teller in these times when stories are considered not quite as satisfying as statements and statements not quite as satisfying as statistics’. ‘But’, she continued, ‘in the long run, a people is known, not by its statements or statistics, but by the stories it tells’. And so the dogged persistence of theologians and artists. Indeed, it is stories – in fact, a particular, if not very short or simple, story – that Brewer’s book is primarily concerned to tell. That his chosen medium is the visual arts reminded me of something that NT Wright once said, and which is, I think, worth repeating:

We have lived for too long with the arts as the pretty bit around the edge with the reality as a non-artistic thing in the middle. But the world is charged with the grandeur of God. Why should we not celebrate and rejoice in that? And the answer sometimes is because the world is also a messy and nasty and horrible place. And, of course, some artists make a living out of representing the world as a very ugly and wicked and horrible place. And our culture has slid in both directions so that we have got sentimental art on the one hand and brutalist art [on] the other. And if you want to find sentimental art then, tragically, the church is often a good place to look, as people when they want to paint religious pictures screen out the nasty bits. But genuine art, I believe, takes seriously the fact that the world is full of the glory of God, and that it will be full as the waters cover the sea, and, at present (Rom 8), it is groaning in travail. Genuine art responds to that triple awareness: of what is true (the beauty that is there), of what will be true (the ultimate beauty), and of the pain of the present, and holds them together as the psalms do, and asks why and what and where are we … And our generation needs us to do that not simply to decorate the gospel but to announce the gospel. Because again and again, when you can do that you open up hermeneutic space for people whose minds are so closed by secularism that they just literally cannot imagine any other way of the world being. I have debated in public … with colleagues in the New Testament guild who refuse to believe in the bodily resurrection and, again and again, the bottom line is when they say ‘I just can’t imagine that’, the answer is, ‘Smarten up your imagination’. And the way to do that is not to beat them over the head with dogma but so to create a world of mystery and beauty and possibility, that actually there are some pieces of music which when you come out of them it is much easier to say ‘I believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit’ than when you went in.

We have lived for too long with the arts as the pretty bit around the edge with the reality as a non-artistic thing in the middle. But the world is charged with the grandeur of God. Why should we not celebrate and rejoice in that? And the answer sometimes is because the world is also a messy and nasty and horrible place. And, of course, some artists make a living out of representing the world as a very ugly and wicked and horrible place. And our culture has slid in both directions so that we have got sentimental art on the one hand and brutalist art [on] the other. And if you want to find sentimental art then, tragically, the church is often a good place to look, as people when they want to paint religious pictures screen out the nasty bits. But genuine art, I believe, takes seriously the fact that the world is full of the glory of God, and that it will be full as the waters cover the sea, and, at present (Rom 8), it is groaning in travail. Genuine art responds to that triple awareness: of what is true (the beauty that is there), of what will be true (the ultimate beauty), and of the pain of the present, and holds them together as the psalms do, and asks why and what and where are we … And our generation needs us to do that not simply to decorate the gospel but to announce the gospel. Because again and again, when you can do that you open up hermeneutic space for people whose minds are so closed by secularism that they just literally cannot imagine any other way of the world being. I have debated in public … with colleagues in the New Testament guild who refuse to believe in the bodily resurrection and, again and again, the bottom line is when they say ‘I just can’t imagine that’, the answer is, ‘Smarten up your imagination’. And the way to do that is not to beat them over the head with dogma but so to create a world of mystery and beauty and possibility, that actually there are some pieces of music which when you come out of them it is much easier to say ‘I believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit’ than when you went in.

Art that Tells the Story is grounded upon the premise that artists and theologians can not only help us to see better, but also that like all human gestures toward the truth of things, the work of artists can become an instrument through which God calls for our attention. And here I wish to conclude by re-sounding a call trumpeted by Michael Austin in Explorations in Art, Theology and Imagination:

Theologians must be on their guard against commandeering art for religion, must allow artists to speak to them in their own language, and must try to make what they can of what they hear. What they will hear will tell of correspondences and connections, of similarities, of interactions and of parallel interpretations and perceptions which will suggest a far closer relationship of essence between art and religion than many theologians have been prepared to acknowledge. As the churches at the beginning of the twenty-first century become more fearful and therefore more conservative there may be fewer theologians prepared to take the risks that embracing a truly incarnational religion demands of them. In particular what they hear may suggest to them that their many (often contradictory) understandings of God and redemption and salvation in Christ need to be radically reconsidered if a new world is to be made.

Chris Brewer’s Art that Tells the Story is just such an attempt. It’s good stuff.

Fred Williams: Intimate Horizons

The day has been filled with a number of highlights, not least of which was the discovery of a piece about Fred Williams by Peter Conrad in the latest issue of The Monthly. Williams is certainly among my favourite painters, from Australia or elsewhere. I well remember his show at the National Gallery of Victoria back in the 80s – it was absolutely mind-blowing. Anyway, here’s a wee snippet from Conrad’s piece:

The day has been filled with a number of highlights, not least of which was the discovery of a piece about Fred Williams by Peter Conrad in the latest issue of The Monthly. Williams is certainly among my favourite painters, from Australia or elsewhere. I well remember his show at the National Gallery of Victoria back in the 80s – it was absolutely mind-blowing. Anyway, here’s a wee snippet from Conrad’s piece:

In 1947 the art historian Kenneth Clark sympathised with Sidney Nolan’s early efforts to paint “the Australian countryside (if one can call that inhospitable fringe between sea and desert by such a reassuring name)”. Clark suspected that art, with its play of bright but not blinding light and soft shadow, was disabled because Australia contained “no dark woods … no thick, sappy substances”, no excuse for pictorial impasto.

A decade later, Fred Williams returned to Melbourne after spending six years as a student in London and began to prove Clark wrong. The work Williams had done in England – mostly figurative, with wistful urban vignettes of buskers and beggars, or souvenirs of the desperately jaunty acrobats and comedians in the last remaining music halls – proved to be a false start. In Australia the land was starkly depopulated bush, with no workers tidily pruning the trees, as seen in one of his English etchings, and no church steeples to organise and sanctify the view. The affectionately downtrodden rural scenery of Constable seemed irrelevant, as did Turner’s frothy sublimity. On a trip to Kosciuszko National Park, Williams discovered something quite unlike the Alps that had excited the European Romantics. Storm clouds pummelled the Australian mountains in an aerial bombardment and snow, as it settled onto rock, sketched grotesque, leering faces.

The geometrical boulders painted by Cézanne were of some help, because they reminded Williams to consider what the land was made of, but his visual education did little to prepare him for his first expeditions to Mittagong in the Southern Highlands, New South Wales, and Upwey in the Dandenongs, Victoria. He was bewildered by the lack of a skyline, and by the eye’s inability to find a track through the mess of scrub: perspective is an urban convenience, allowing us to travel to the horizon in a straight line, and Australian space refused to be regulated.

You can read the whole piece here.

I was especially pleased, too, to read that the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra will be hosting an exhibition of Williams’ work entitled ‘Infinite Horizons’, from 12 August to 6 November 2011. It’s enough to make one want to jump onto a plane, very soon.

The good, the beautiful and the true

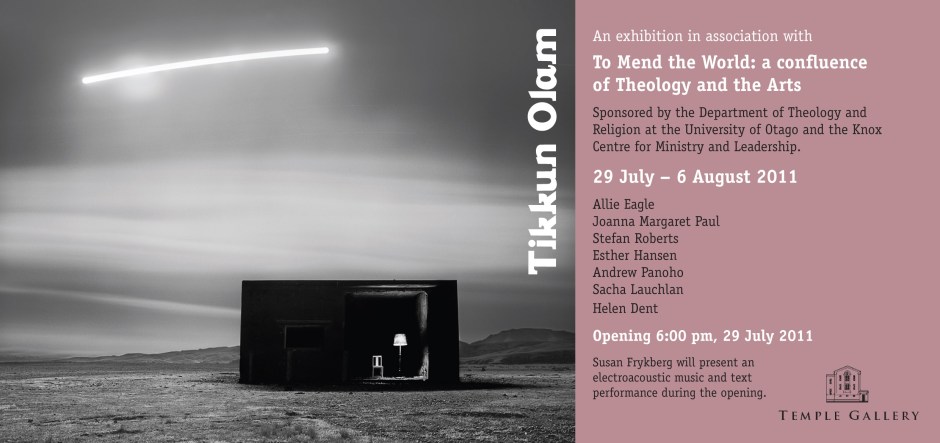

Last week, a conference and exhibition (actually, the exhibition is still running) took place which I had the privilege to help organise. We chose for our theme the Hebrew phrase ‘Tikkun Olam’ – to mend the world – and invited artists and theologians to converse together about the following questions: Can there be repair? Can art and can theology tell the truth of the world’s woundedness and still speak of hope?

Last week, a conference and exhibition (actually, the exhibition is still running) took place which I had the privilege to help organise. We chose for our theme the Hebrew phrase ‘Tikkun Olam’ – to mend the world – and invited artists and theologians to converse together about the following questions: Can there be repair? Can art and can theology tell the truth of the world’s woundedness and still speak of hope?

One of the themes to arise from the conversations concerned the Church’s long and deep indebtment to the three-fold notion of the good, the beautiful and the true, a notion articulated in Plato and given significant mileage through Thomas Aquinas in whom it reaches something of a dead end because in the final analysis Thomas’s articulation – like Kant’s after him – is too divorced from the particular form that God’s life actually takes in the world. For God’s beauty is not, as some suggest, the infinite serenity of God’s life. Rather, God’s beauty is the infinite drama of God’s life, a drama which, as Jonathan Edwards so wonderfully articulated, draws attention to God’s intrinsic plurality – God is beautiful precisely because God is Triune.

And so it is perhaps not too odd that the twentieth century which witnessed something of a renaissance of interest in the doctrine of the Trinity also witnessed a widescale broadening of the notion of beauty in the discourse of aesthetics. Beauty was no longer understood in the narrow terms outlined by Kant and others, and it became rightly recognised as having to do, in John de Gruchy’s words, with ‘the experience and perception of reality that we associate with the imagination and creativity, with metaphor and symbol, with games, playfulness, and friendship. The arts, whether fine or popular in all their manifold forms are central to aesthetics because they embody and express this dimension of experience, they evoke memories and suggest possibilities, thereby enabling us to see reality differently’.

Where beauty has been banished from contemporary aesthetic discourse, it has largely been in ‘reaction to the aestheticism of those who pursued beauty for its own sake, a Romantic escapism oblivious to the ugly realities of a world gripped by oppression’. But movements birthed by reaction alone are doomed to fail; and anyway, any account of aesthetics which claims the name ‘Christian’ will have to deal with the fact that the very centre of divine unveiling recalls that the beautiful and the ugly are not so easy to disentangle as we might first expect. Indeed, a Christian account of beauty can neither ignore nor offer easy escape from evil.

It is not, therefore, improper – indeed, it may be incumbent upon Christian theologians and artists – to approach the question of beauty through a consideration of its opposite, namely ugliness. Indeed, it is sometimes the case, as Theodor Adorno observes, that ‘art has to make use of the ugly in order to denounce the world which creates and recreates ugliness in its own image’. John de Gruchy suggests that ‘it is precisely this protest against unjust ugliness that reinforces the value and significance of beauty as something potentially redemptive. Indeed, if aesthetics were just about the beautiful we would never really understand “the dynamic life inherent in the concept of beauty”’. If ugliness has the capacity to destroy life, then Dostoevsky’s claim that ‘beauty will save the world’ invites us to not only (as PT Forsyth put it) ‘distrust the easy optimism of the merely happy creeds’, but also to see the invitation towards theological aesthetics as about faith seeking to understand reality – in its ugly forms too – from the vista of the beauty of God revealed primarily in the bloodied wounds of the cross where all that is ugly is transfigured by a profundity of beauty. Such beauty, as Karl Barth insists, ‘embraces death as well as life, fear as well as joy, what we might call the ugly as well as what we might call the beautiful’. To speak of beauty in its deepest reality is, in other words, to speak not just of any beauty, but rather of a very specific beauty. Indeed, it is beauty so specific that it goes by a particular name – Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ – who he is and what God does in him – is the very beauty of God.

To Mend the World: gratitude

Those for whom Per Crucem ad Lucem is a regular stopping place will know that recent months have seen me involved in birthing a twin project called To Mend the World. With the exhibition now in full swing (at the Temple Gallery) and the conference furniture packed away, it’s good to be able to pause a while, to claim some space to do an initial reflection. It has been a wonderful and wonderfully-full two days.

Those for whom Per Crucem ad Lucem is a regular stopping place will know that recent months have seen me involved in birthing a twin project called To Mend the World. With the exhibition now in full swing (at the Temple Gallery) and the conference furniture packed away, it’s good to be able to pause a while, to claim some space to do an initial reflection. It has been a wonderful and wonderfully-full two days.

It has certainly been a privilege to be part of a small band who together envisioned the conference, whose energy made it possible, and whose commitment to the conversation between art and theology is long and outstanding. We had a great line up of speakers who, via some wonderfully-stimulating presentations, modelled what the organisers of the conference had hoped – a humble and respectful but no less critical and intelligent conversation by artists and theologians around the conference theme of ‘Tikkun olam’. We were overwhelmed by the number of people who registered for the conference – around double what we had initially anticipated – plus a number of welcomed-walk ins too, all of whom engaged in the conversations with enthusiasm and grace. Like every conference of which I’ve been a part, this one too provided opportunity to re-connect with friends, to finally put some faces to names, and to meet in-the-flesh those with whom one has only ever ‘met’ in e-land. Of this latter category, it was really great to finally meet Paul Fromont, with whom I enjoyed a very rewarding conversation and my first pint of Moe Methode.

An event of this kind is an all-too-rare thing, and its happening has been both a real joy and a long-time goal for me personally. I hope that all who attended left the event as encouraged, challenged and enriched as I was by the encounter.

Speaking of theology and the arts, here’s a few recent links of interest:

- Chris Brewer interviews Alfonse Borysewicz – Part I and Part II.

- Chris Smith reviews Bill Dyrness’ latest book, Poetic Theology: God and the Poetics of Everyday Life.

- Jonathan Master reviews Beauty Will Save the World: Recovering the Human in an Ideological Age by Gregory Wolfe.

- Peter M. Candler on The Tree of Life and the Lamb of God.

- Jim Gordon on Hieronymous Bosch and Being Human.

‘To Mend the World’: conference and exhibition

I want to give the ‘To Mend the World’ conference and exhibition one final plug. The conference runs from 29–30 July, and the exhibition from 29 July through to 6 August. It really is shaping up to be a very exciting twin-project, with an impressive line-up of speakers and artists. Registration for the conference has exceeded expectation, and is still open if you’re keen to attend.

Nota Bene

- John Cleary interviews He Qi.

- David Congdon reflects on analytic theology.

- David Anderson on R.S. Thomas: Poet of the Cross.

- Dateline airs a program on the Restorative Justice Project.

- An Encounter program on the poetry and prayers of Kevin Hart.

Dunedin to host two theology conferences

There can be little doubt that the 5-month delay of the parousia (until 21 October) is principally so that Dunedin – the global centre for theology, semi-decent coffee, and steep streets – can serve as host to two planned theological conferences.

There can be little doubt that the 5-month delay of the parousia (until 21 October) is principally so that Dunedin – the global centre for theology, semi-decent coffee, and steep streets – can serve as host to two planned theological conferences.

The first, from July 29–30, is a conference on theology and art titled ‘To Mend the World’. The keynote speaker will be Professor Bill Dyrness from Fuller Theological Seminary and the conference will include an exhibition on the conference theme at the Temple Gallery, and a special screening of ‘The Insatiable Moon’ followed by discussion with the writer Mike Riddell. Further details here.

The second conference, to be held from September 2–3, will offer a Christian response to the phenomenon of ‘The New Atheism’ as represented by writers like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. This conference, ‘The New Atheism: A Christian Response’, will be jointly hosted by the Faraday Institute at Cambridge University and the University of Otago. Further details here.

To Mend the World: a confluence of theology and the arts

The sixteenth-century Jewish mystic, Isaac Luria, made much of the notion of tikkun olam, a phrase which we might translate as ‘to mend the world’. Luria believed that the Creator of all things, in deciding to create a world, drew in – contracted – the divine breath in order to make room for the creation coming into being. In this enlarged space, the Creator then set vessels and poured into them the radiance of the divine light. But the light was too brilliant for the vessels, causing them to shatter and scatter widely. Since then, the vocation given to human person has consisted of picking up and to trying to mend or refashion the shards of creation.

The sixteenth-century Jewish mystic, Isaac Luria, made much of the notion of tikkun olam, a phrase which we might translate as ‘to mend the world’. Luria believed that the Creator of all things, in deciding to create a world, drew in – contracted – the divine breath in order to make room for the creation coming into being. In this enlarged space, the Creator then set vessels and poured into them the radiance of the divine light. But the light was too brilliant for the vessels, causing them to shatter and scatter widely. Since then, the vocation given to human person has consisted of picking up and to trying to mend or refashion the shards of creation.

Tikkun olam is also the theme of a conference and exhibition that I’m involved in organising, and which will take place in Dunedin this July. It is shaping up to be a very exciting twin-project, with an impressive line-up of speakers and artists. Registration for the conference has exceeded expectation for this stage so far out from the date, is still open, and there’s still some time to get in on the ‘early-bird’ rate.

Around the traps: To the memory of ulcers scraped with a tin spoon

- Rowan Williams on the Big Society.

- Les Murray and the Poetry of Depression, a review-piece by Meghan O’Rourke.

- The latest edition of Zeitschrift für Neuere Theologiegeschichte (Vol. 18, No. 1, April 2011) is now available and includes an essay on ‘Albrecht Ritschl and the Tübingen School. A neglected link in the history of 19th century theology’ by Johannes Zachhuber. The Forsythian in me is excited to see this. [I also found a version of this essay here].

- The preacher your preacher could preach like.

- Alain Badiou responds to Jean-Luc Nancy on Libya, and on elsewhere in the Middle East.

- Kurt Vonnegut on the simple shapes of stories.

- Warner Brothers wins the Roger Awards.

- The latest edition of the Journal of Reformed Theology (5/1, 2011) is out.

- Robert Manne on the untold story of Julian Assange.

- T&T Clark launch Continuum e-Books.

- Michael Jensen is blogging on human nature and the arts (parts I, II, III, IV).

- The Postcolonial Theology Network and Whitley College are hosting a conference – Story Weaving: Colonial Contexts and Postcolonial Theology.

- Michael Jinkins on Martin Luther King’s questions about the church.

- Bruce Hamill reflects on what the church is called to be in our world.

- Travis McMaken has been posting on and linking to posts on David Kelsey’s 2011 Warfield Lectures (parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI).

- John Pilger on Westminster, Libya and Yemen.

To Mend the World (Tikkun Olam): a confluence of theology and the arts

The traditions of artistic expression and of Christian faith are richly intertwined. Artists help us to see differently. They draw attention to the order of things, and to their disorder. They help us to see the world’s beauty; they present us with its simplicity, and confront us with its tragedy. Now and again the work of artists becomes something more. Like all human gestures toward the truth of things, the work of artists can become an instrument through which God calls for our attention.

The traditions of artistic expression and of Christian faith are richly intertwined. Artists help us to see differently. They draw attention to the order of things, and to their disorder. They help us to see the world’s beauty; they present us with its simplicity, and confront us with its tragedy. Now and again the work of artists becomes something more. Like all human gestures toward the truth of things, the work of artists can become an instrument through which God calls for our attention.

Attentiveness to God is also the task of Christian theology. Theology is, simply, a mode of attentiveness to the self-disclosure of God, and a striving to see the truth of things in light of that self-disclosure.

A group of us here in Dunedin are organising a conference and exhibition which will bring together artists and theologians to foster this intertwining.

The conference and exhibition are premised on the conviction that artists, theologians and people of faith have things to learn from one another, things about the complex inter-relationality of life, and about a coherence of things given and sustained by God.

The aim is to bring painters, poets, musicians, indeed, artists of all descriptions, together with theologians, and with people of faith, to explore a particular theme; can there be repair? Can there be a mending of the world, wounded as it is by war, by hatred, by exploitation and by neglect. We have chosen the Hebrew phrase ‘Tikkun Olam’ – to mend the world – to signal the conference theme, and to pose the question: Can there be repair? Can art and can theology tell the truth of the world’s woundedness and still speak of hope? Can poetry still be written after unspeakable tragedy, a concerto played, a brush taken up? Must it be written, played, or taken up, perhaps more than ever?

We invite you to join us in exploring this theme.

Conference Dates & Place

29–30 July 2011. Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership, Knox College, Arden Street, Dunedin.

Conference Speakers

The theme will be addressed by a range of speakers including Professor William Dyrness, Professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary, California.

Exhibition Dates & Place

An exhibition of work that picks up the theme of the conference – To mend the world: Tikkun Olam – is also being organised and will run for a week over the period of the conference.

Invitation to Artists

Artists are invited to participate in a group exhibition to be held at a Dunedin gallery. Information about submissions is available here.

More information on both the conference and exhibition is available here.

‘Life in Gaza Today’: an exhibition

Christian World Service are sponsoring an exhibition of paintings by Christian and Muslim children and adult artists who live in Gaza.

Where: Knox Church, 449 George St, Dunedin, in the Gathering Area.

When: 20–22 December 2010, 3–5 January 2011. 10.00 am – 4.00 pm.

The exhibition will be launched on Monday 20 December @ 5.15pm with a talk by Mai Tamimi.

Enquiries: email or phone (03) 477 0229.

Are images of Jesus idolatrous?

It is impossible, it seems, for a theologian to think seriously about the arts and not before long be confronted with the question of visual representations of God and, for the Christian theologian, of God as incarnate. The Orthodox and the Reformed traditions, in particular, have long taken this question with the utmost seriousness (and that beside heated debates on the communicatio idiomatum or of those on the question of Christ’s presence in the Supper). The four main objections seem to be:

It is impossible, it seems, for a theologian to think seriously about the arts and not before long be confronted with the question of visual representations of God and, for the Christian theologian, of God as incarnate. The Orthodox and the Reformed traditions, in particular, have long taken this question with the utmost seriousness (and that beside heated debates on the communicatio idiomatum or of those on the question of Christ’s presence in the Supper). The four main objections seem to be:

# 1. Violation of the second commandment

There are no commands to make pictures of our Lord. In fact such pictures, it is argued, clearly violate the second commandment. There are issues here of the ongoing question of idolatry, witnessed to in the Old Testament’s depiction of pagan idols described as being made of gold, silver, wood, and stone – i.e. of the ‘stuff’ of creation, of the work of human hands, unable to speak, see, hear, smell, eat, grasp, or feel, and powerless either to injure or to benefit (Ps 135:15–18). And, of course, there is the Decalogue’s second commandment:

‘You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth’. (Exodus 20:3–4)

Does this commandment put a fence around what artists can – and cannot – depict of God? Are images of Jesus – whether in Sunday School books, galleries, or spaces dedicated for public worship – idolatry? And if not, then how ought we understand the relation between the unique and unrepeatable revelation of God in the incarnation (and that attested to in the inscripturated word and from the Church’s pulpit, font and table) and visual depictions of that Word?

# 2. All attempts are false representations

Since no accurate representation of Christ can be produced by creatures, all attempts are false representations and can only promote idolatry.

# 3. We don’t know what Jesus looks like

Despite passages like Isaiah 53:2 and Revelation 1:13–16, the Bible does not give us enough information to make a faithful representation of Christ’s physical appearance. Therefore, it is obvious that God does not sanction portraits of God’s Son.

# 4. All plastic (i.e. material) representations of Jesus implicitly promote the ancient heresy of Nestorianism

# 4. All plastic (i.e. material) representations of Jesus implicitly promote the ancient heresy of Nestorianism

The most serious objection to artists’ attempts to represent Jesus pictorially has been associated with this charge of Nestorianism. In other words, even if we had a photo of Jesus which depicted what he looked like, no human artistry can portray Christ’s divine nature. Therefore, all attempts are a lie and portray Jesus as infinitely less, or other, than he is as the God-human. This argument was proposed by the Council of Constantinople in 754:

‘If any person shall divide human nature, united to the Person of God the Word; and, having it only in the imagination of his mind, shall therefore, attempt to paint the same in an Image; let him be holden as accursed. If any person shall divide Christ, being but one, into two persons; placing on the one side the Son of God, and on the other side the son of Mary; neither doth confess the continual union that is made; and by that reason doth paint in an Image of the son of Mary, as subsisting by himself; let him be accursed. If any person shall paint in an Image the human nature, being deified by the uniting thereof to God the Word; separating the same as it were from the Godhead assumpted and deified; let him be holden as accursed’.

Regarding this council Philip Schaff, in History of the Christian Church. Volume IV: Mediæval Christianity from Gregory I to Gregory VI; A.D. 590–1073, writes:

The council [of Constantinople, 754], appealing to the second commandment and other Scripture passages denouncing idolatry (Rom. 1:23, 25; John 4:24), and opinions of the Fathers (Epiphanius, Eusebius, Gregory Nazianzen, Chrysostom, etc.), condemned and forbade the public and private worship of sacred images on pain of deposition and excommunication … It denounced all religious representations by painter or sculptor as presumptuous, pagan and idolatrous. Those who make pictures of the Saviour, who is God as well as man in one inseparable person, either limit the incomprehensible Godhead to the bounds of created flesh, or confound his two natures, like Eutyches, or separate them, like Nestorius, or deny his Godhead, like Arius; and those who worship such a picture are guilty of the same heresy and blasphemy. The eucharist alone is the proper image of Christ. (pp. 457–8.)

This issue is just one of the many in which the great twentieth-century theologian Karl Barth and his reformation great-grandfather, John Calvin, agree. They both held that:

- Preaching and sacraments are central to the community’s activity;

- That static works are a distraction to the ‘listening community’;

- That the community should not be bound to a particular conception of Jesus;

- That even the best art cannot ‘display Jesus Christ in his truth, i.e., in his unity as true Son of God and Son of Man. There will necessarily be either on the one side, as in the great Italians, an abstract and docetic over-emphasis on His deity, or on the other, as in Rembrandt, an equally abstract, ebionite over-emphasis on His humanity, so that even with the best of intentions error will be promoted’ (Barth, CD IV.3.2, 867). To be sure, Barth had already anticipated this move in CD IV.2 when he insisted that Jesus Christ cannot be known in his humanity as abstracted from his divine sonship. See CD IV.2, 102–3.

- ‘Whatever [people] learn of God in images is futile’ (Calvin, Institutes, I.xi.5). God’s majesty ‘is far above the perception of our eyes … Even if the use of images contained nothing evil, it still has no value for teaching’ (Inst., I.xi.12); and

- ‘Theology cannot fix upon, consider, and put into words any truths which rest on or are moved by themselves – neither an abstract truth about God nor about man nor about the intercourse between God and man. It can never verify, reflect or report in a monologue. Incidentally, let it be said that there is no theological visual art. Since it is an event, the humanity of God does not permit itself to be fixed in an image’ (Barth, The Humanity of God, 57).

That art is concerned with ‘earthly, creaturely things’ is reflected in Karl Barth’s scathing critique of attempts to visualise the ‘inaccessible and incomprehensible side of the created world’, and he lists ‘heaven’, and Christ’s resurrection and ascension as examples: ‘There is no sense in trying to visualise the ascension as a literal event, like going up in a balloon. The achievements of Christian art in this field are amongst its worst perpetrations’ (CD III.2, 453). And, on the resurrection, he writes:

That art is concerned with ‘earthly, creaturely things’ is reflected in Karl Barth’s scathing critique of attempts to visualise the ‘inaccessible and incomprehensible side of the created world’, and he lists ‘heaven’, and Christ’s resurrection and ascension as examples: ‘There is no sense in trying to visualise the ascension as a literal event, like going up in a balloon. The achievements of Christian art in this field are amongst its worst perpetrations’ (CD III.2, 453). And, on the resurrection, he writes:

There is something else, however, which the Easter records and the whole of the New Testament say but wisely do not describe. In the appearances He not only came from death, but from His awakening from the dead. The New Testament almost always puts it in this way: “from the dead.” From the innumerable host of the dead this one man, who was the Son of God, was summoned and awakened and reconstituted as a living man, the same man as He had been before. This second thing which the New Testament declares but never attempts to describe is the decisive factor. What was there actually to describe? God awakened Him and so He “rose again.” If only Christian art had refrained from the attempt to depict it! He comes from this event which cannot be described or represented – that God awakened Him. (Barth, CD IV.2, 152)

While Barth and Calvin could and did find proper recognition of the gift of God’s love expressed in human culture, they both failed to find in their theology a positive place for the plastic arts that they could find, for example, in music. Ah Wolfgang!

So what ought we make of Barth’s – and others (e.g. Calvin, Kierkegaard) – judgement against visual representations of Jesus? Are visual representations of Jesus really any more susceptible than words (poetry, sermons, etc) about Jesus? (One recalls here Calvin’s insistence that it is the heart that is factory of idols.) Does not God’s act of redeeming creation not extend to the arts’ service of giving an account to the creatureliness of God in Jesus Christ? Does Barth’s and Calvin’s rejection misunderstand the nature of the dynamic and continuing event which is the relationship of the viewer of a painting or a sculpture with the artwork, and of the freedom of the Word in that event? (See Michael Austin, Explorations in Art, Theology and Imagination, 21.)

For most of the Reformed, theology is something that is meant to be done with words, and not with images. But, of course, every decision we make about how we choose to communicate the good news is loaded with visual symbolism and reinforces a perception that God communicates with us in a particular kind of way. The question, therefore, is not, whether or not we should communicate visually; it is, rather, how we do so and what we say when we do.

One of the things that good art does is to shed light on the true nature of things; it broadens our horizons, enriches our capacity to see, alerts us to dimensions of reality that we had not seen before, and for which words, sometimes, are simply not enough. The arts help us to birth the kind of imagination and re-imagination that the good news itself fosters and encourages and demands and makes and invites. Artists see differently, but no less truthfully than scientists, how things are with the world. If we are to walk in our world well, and justly and with the mercy of God, then we cannot do so without the kind of re-imagining of reality and of human society that the arts promote and invite.

‘We have lived for too long with the arts as the pretty bit around the edge with the reality as a non-artistic thing in the middle. But the world is charged with the grandeur of God. Why should we not celebrate and rejoice in that? And the answer sometimes is because the world is also a messy and nasty and horrible place. And, of course, some artists make a living out of representing the world as a very ugly and wicked and horrible place. And our culture has slid in both directions so that we have got sentimental art on the one hand and brutalist art in the other. And if you want to find sentimental art then, tragically, the church is often a good place to look, as people when they want to paint religious pictures screen out the nasty bits. But genuine art, I believe, takes seriously the fact that the world is full of the glory of God, and that it will be full as the waters cover the sea, and, at present (Rom 8), it is groaning in travail. Genuine art responds to that triple awareness: of what is true (the beauty that is there), of what will be true (the ultimate beauty), and of the pain of the present, and holds them together as the psalms do, and asks why and what and where are we. You can do that in music, and you can do that in painting. And our generation needs us to do that not simply to decorate the gospel but to announce the gospel. Because again and again, when you can do that you open up hermeneutic space for people whose minds are so closed by secularism that they just literally cannot imagine any other way of the world being. I have debated in public in America with colleagues in the New Testament guild who refuse to believe in the bodily resurrection and, again and again, the bottom line is when they say ‘I just can’t imagine that’, the answer is, ‘Smarten up your imagination’. And the way to do that is not to beat them over the head with dogma but so to create a world of mystery and beauty and possibility, that actually there are some pieces of music which when you come out of them it is much easier to say ‘I believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit’ than when you went in’. (NT Wright, ‘Jesus, the Cross and the Power of God’. Conference paper presented at European Leaders’ Conference, Warsaw, February, 2006).

Of course, as Murray Rae recently reminded a bunch of us here in Dunedin, the risk-taking work of re-imagining means that there can be no guarantee that misunderstanding and misinterpretation will be avoided. But neither do we have any such guarantee in the use of our words. In both cases, it seems, what we offer is an act of faith given under God’s imperative that we should share the good news. We offer in Christian witness so much as we have understood, knowing it to be partial, inadequate, and marred by our own sinfulness. And we do so in the name and under the inspiration of the God who makes eloquent the stumbling witness of our faith, and moulds our communication to good and loving purpose. It’s risky, but it is, it seems, God’s risk too.

Perhaps a few words from John de Gruchy would be a fitting way to conclude this post:

Art in itself cannot change society, but good art, whatever its form, helps us both individually and corporately to perceive reality in a new way, and by so doing, it opens up possibilities of transformation. In this way art has the potential to change both our personal and corporate consciousness and perception, challenging perceived reality and enabling us to remember what was best in the past even as it evokes fresh images that serve transformation in the present. This it does through its ability to evoke imagination and wonder, causing us to pause and reflect and thereby opening up the possibility of changing our perception and ultimately our lives … From a Christian perspective, the supreme image that contradicts the inhuman and in doing so becomes the icon of redemption is that of the incarnate, crucified and risen Christ. So it is not surprising that artists through the centuries have sought to represent that alien beauty as a counter to the ugliness of injustice. We are not redeemed by art nor by beauty alone, but by the holy beauty which is revealed in Christ and which, through the Spirit evokes wonder and stirs our imagination. (John W. de Gruchy, ‘Holy Beauty: A Reformed Perspective on Aesthetics Within a World of Ugly Injustice’ in Reformed Theology for the Third Christian Millennium: The 2001 Sprunt Lectures, 14–5).

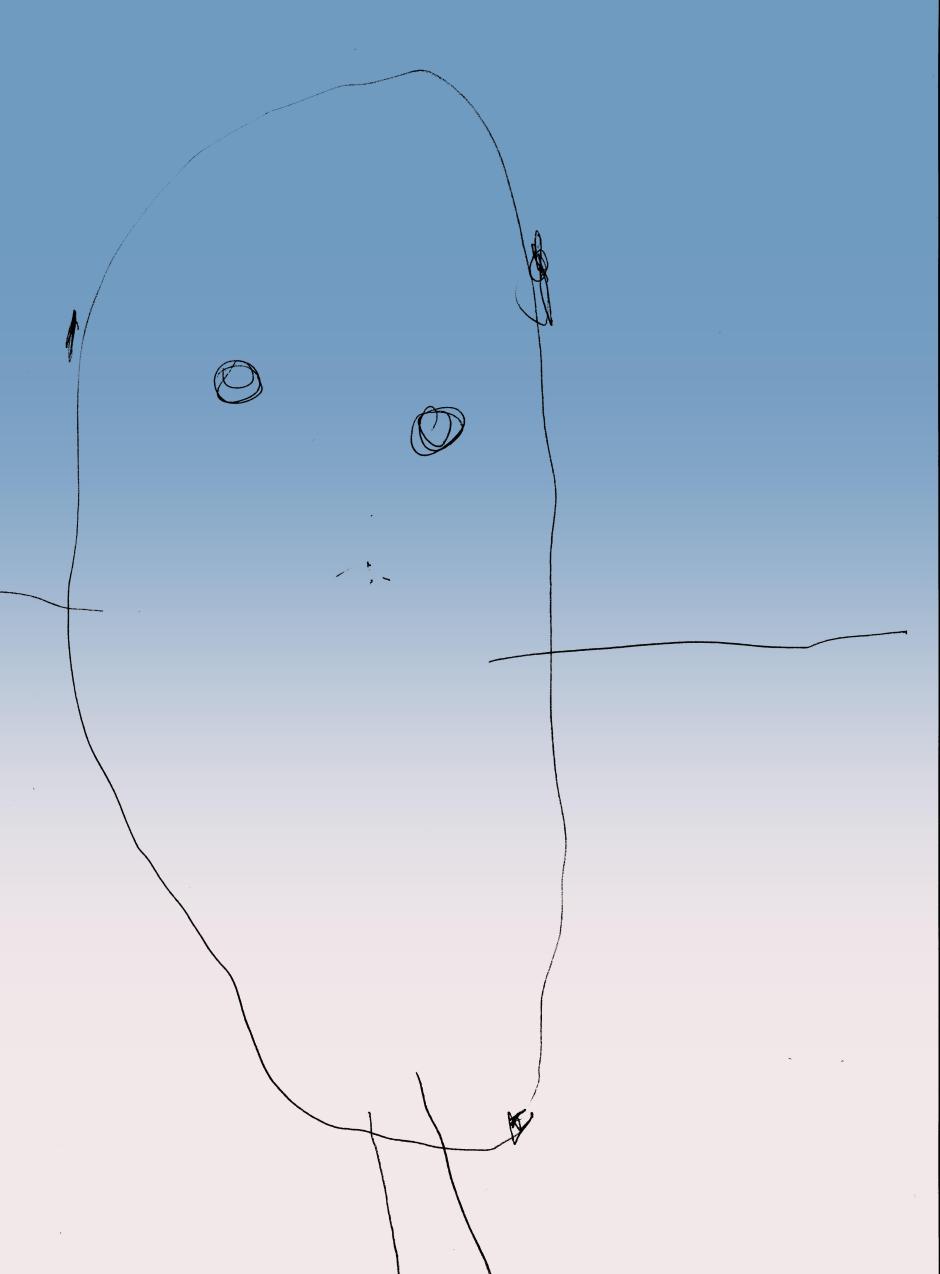

‘Look, daddy, this is you’: A view from the other side

This is how my daughter sees me. Little wonder that she rarely takes me seriously.

… and apparently I look nothing at all like Jesus (must be Jesus’s serious acne problem that distinguishes us), whom she also rarely takes seriously:

[A note: to my shame, my daughter remains completely ignorant – or just dismissive – of Calvin’s and Barth’s and Kierkegaard’s judgement against visual representations of Jesus. Neither does she appear to have learnt the Ten Commandments yet (and certainly not the big #5). At this rate, she’ll make a great Presbyterian!].

Recent wanderings: ‘The sudden disappointment of a hope leaves a scar which the ultimate fulfillment of that hope never entirely removes’

- An attack on liberal Anglicanism – and on art?

- Some words for teachers on the relationship between teaching styles and learning styles

- David Fergusson on Rudolph Bultmann

- Michael Gorman on why Christmas ought not include singing Happy Birthday to Jesus

- Saddened to hear of the news of Edward Schillebeeckx’s passing. Schillebeeckx’s was one of the great voices in recent years, a true scholar and gentle prophet of reform. Here’s what he had to say twenty years ago: ‘My concern is that the further we move away in history from Vatican II, the more some people begin to interpret unity as uniformity. They seem to want to go back to the monolithic church which must form a bulwark on the one hand against communism and on the other hand against the Western liberal consumer society. I think that above all in the West, with its pluralist society, such an ideal of a monolith church is out of date and runs into a blind alley. And there is the danger that in that case, people with that ideal before their eyes will begin to force the church in the direction of a ghetto church, a church of the little flock, the holy remnant. But though the church is not of this world, it is of men and women. Men and women who are believing subjects of the church’. This mature voice once stated, in God Is New Each Moment, that ecumenism means ‘that we have to bear in mind the great Christian tradition that can be found in all the Christian churches – the Catholica, which does not in itself coincide with the empirical phenomenon of the Roman Catholic Church … In that sense, my work is, I think, a valid contribution to the unity of the church, in which there may be all kinds of differences, but in which the one Church community recognizes itself in the other communities and they recognize themselves in it’ (p. 74).

- Some disturbing religious activities

- An interesting interview with Better World Books

- Robert Minto brings Simone Weil and Graham Greene’s Whiskey Priest into the same frame

- Andrew Errington shares some Seamus Heaney

- David Guretzki begins some reflections on Barth’s Credo

- Jim Gordon posts on the importance of ideas in the practical renewal of the church

- James Merrick shares some Marilynne Robinson on evangelicalism and Protestant liberalism

- Finally, as one who has posted on beer before, I was delighted to read Arni Zachariasse’s post on ‘6 reasons why your church needs (more) beer’:

- Beer is good for the community. Beer reduced inhibitions and nowhere are people more inhibited than in church. Congregants want at least one chair between them and the person next them. Even better if they get the entire pew to themselves. With a few pints down them, on the other hand, that invisible wall, that awkward space is all but gone. People will start laughing together, they will start crying together. They will even hug! Paul’s “holy kiss” might once again become commonplace, and not a relic of the Bible sped through by embarrassed readers-aloud. In addition to strengthening the ties between those already in the local church, the stranger will be welcomed with open arms, both his presence and his strange thoughts. Which leads me to the second point.

- Beer is good for the church’s communal theological inquiry. Here again alcohol’s inhibition reduction is beneficial. Imagine if people actually asked what was on their mind and weren’t afraid of embarrassing themselves because they weren’t among the chosen few in the front five pews, because they didn’t know the jargon or didn’t worry about having the Bible quoted at them. Imagine if people actually voiced those fleeting thoughts, objections and ideas. Theology would then, at last, actually be done in the church and by the church. Dogmatics, you could say, would finally become church dogmatics. Beer would not only have people doing theology and doing it more freely, but would strengthen people’s ties to the church while simultaneously opening the doors to new ideas from outside the church. (Maybe that’s why church leaders are against alcohol!)

- Beer is good for the worship. Have you ever heard drunk people sing? Of course you have! It’s about 80% of what drunk people do. They don’t do it well, no – but they do it with sincerity! With vocal chords and emotional capabilities lubricated by some good brew, the church’s worship would be amazing. It would be loud, brash, unashamed and totally in keeping with that unruly Holy Spirit. Liturgy would be shouted back at the minister. Hymns and choruses would sung on top of lungs along to bands unafraid to actually jam. And I can’t imagine what would happen in charismatic churches with all their tongue speaking and other pneumatalogical craziness.

- Beer is good for moral reflection. If you’re like 90% of Evangelicals, you’ve been taught that beer is bad. Consuming of alcohol is something that heathens and liberals do. But look at it this way: Drinking a beer is a physical manifestation of you re-evaluating your morals, of you thinking through, maybe for the first time, how you act out your faith. And it will be an entry into wider reflection, a small, very fun step in the direction of the examined life. And in light of the points raised previously, you’ll do it with your friends and you’ll have a great time.

- Keeping with the morals, beer supports Christian brothers and sisters. Or, more specifically, brothers. Some of the best beers in the world, Trappist beers in particular, are made by monks in Belgium and Holland. Trappist monastics brew this heavenly ales in order to keep their communities afloat and to support charitable causes. By buying Trappist beer you not only get some of the best tasting beer you’ll ever try, but you’ll also keep some of your brothers in Christ in their special monastic service.

- Beer will introduce you to the finer things in life. Not all beer will do this, granted, but if you do take my advice and buy some Trappist beer you will be introduced to a fascinating world of subtle flavours that will titillate your taste buds and satisfy your soul. Now, I’m not suggesting hedonism for it’s own vacuous sake. I’m suggesting that enjoying God’s gifts can be a worshipful activity and experience. Slowly savouring a glass of fine beer will inspire deep gratitude to the Lord for the blessings he has bestowed upon you, your ability to enjoy them and for existence itself. Fine beer will further introduce you to other tasty beverages like wine, whiskey, brandy and the like. Which means even more thanksgiving. This thanksgiving is great in solitude, but fantastic communally, with brothers and sisters in the church. Imagine a service of beer tasting. No, imagine the Eucharist with gourmet beer. Beautiful!

Rethinking Serrano’s ‘Piss Christ’

![Andreas Serrano - Piss Christ [1987] Andreas Serrano - Piss Christ [1987]](https://jasongoroncy.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/andreas-serrano-piss-christ-1987.jpg?w=940) ABC’s Encounter Program recently re-ran a conversation with David Freedman (Rabbi, Sydney), Robin Jensen (Professor of the History of Christian Worship and Art, Vanderbilt University, Nashville), Rod Pattenden (Director, Blake Prize for Religious Art), Steven Liew (Plastic surgeon, Sydney), Maureen O’Sullivan (Plastic surgery patient), and Christine Piff (Founder and CEO, Let’s Face It) on the topic of the human face. The conversations reflected on artistic representations of God, and modern cosmetic surgery and its relationship with experiences of facial disfigurement. It was a fascinating program (and it can be downloaded here). One the reflections that struck me was that of Rod Pattenden on Andreas Serrano’s much-debated photograph ‘Piss Christ’. I appreciated being invited (even compelled) to revisit this piece, and, in so doing, rethink and revisit some earlier reflections, questions and conclusions I drew from it both as a piece of art and as a christological statement. Here’s what Pattenden had to say:

ABC’s Encounter Program recently re-ran a conversation with David Freedman (Rabbi, Sydney), Robin Jensen (Professor of the History of Christian Worship and Art, Vanderbilt University, Nashville), Rod Pattenden (Director, Blake Prize for Religious Art), Steven Liew (Plastic surgeon, Sydney), Maureen O’Sullivan (Plastic surgery patient), and Christine Piff (Founder and CEO, Let’s Face It) on the topic of the human face. The conversations reflected on artistic representations of God, and modern cosmetic surgery and its relationship with experiences of facial disfigurement. It was a fascinating program (and it can be downloaded here). One the reflections that struck me was that of Rod Pattenden on Andreas Serrano’s much-debated photograph ‘Piss Christ’. I appreciated being invited (even compelled) to revisit this piece, and, in so doing, rethink and revisit some earlier reflections, questions and conclusions I drew from it both as a piece of art and as a christological statement. Here’s what Pattenden had to say:

This image is an image of a familiar crucifixion. Jesus is spread out upon a cross, probably it’s a little hard to see because we’re seeing it through an orange or red glowing light, with what appears to be bubbles. It looks like the crucifixion has been immersed in this kind of gaseous, underwater, soft orange light. So at first instance, it looks like a very pious image, something very familiar to us, but in a place which seems unfamiliar.

It’s only when we are told that the title is Piss Christ, that we immediately recoil, and as we understand the artist has made a photograph of a traditional plastic crucifix which he’s purchased in a gift store, and placed it in a large – presumably glass – container and filled it with urine, and photographed it. And so you have what seems like a moment of blasphemy, of an offence, of an artist transgressing what is familiar and pious and precious to a believing person, into a situation that seems horrendously offensive.

One of the issues we face as contemporary human beings, is that we live in the age of AIDS, and other diseases which are passed on by human body fluids, and so here is a crucifix placed in body fluids. So the artist – who describes himself as a faithful Catholic, and grew up in a family that was very pious – is actually making a theological connection in this work, about the very humanity of Jesus, and blood, and death, and what it is to suffer.

And what I like about it is that it reminds me that as a religious person I become very familiar with my symbols; I anaesthetise them, I dust them, I make them into gold and precious ornaments, and they become something safe on my shelf. And he reminds me that Jesus actually died and bled and suffered, and that this is offensive and grotesque and difficult. And that that’s a part of what it is to be human. So in the very offence that arises for particularly people of faith, in Serano’s images I think, is an opportunity to revisit the fundamental shock of the crucifixion, and the meaning of Jesus’ death and life.

Andrew Hudgins, in his (pungent and overstated) poem, Andres Serrano, 1987, echoes Pattenden’s claim that it’s in the naming of this photograph that we ‘recoil’, but that it’s not only in the naming:

If we did not know it was cow’s blood and urine,

if we did not know that Serrano had for weeks

hoarded his urine in a plastic vat,

if we did not know the cross was gimcrack plastic,

we would assume it was too beautiful.

We would assume it was the resurrection,

glory, Christ transformed to light by light

because the blood and urine burn like a halo,

and light, as always, light makes it beautiful.

We are born between the urine and the feces,

Augustine says, and so was Christ, if there was a Christ,

skidding into this world as we do

on a tide of blood and urine. Blood, feces, urine—

what the fallen world is made of, and what we make.

He peed, ejaculated, shat, wept, bled—

bled under Pontius Pilate, and I assume

the mutilated god, the criminal,

humiliated god, voided himself

on the cross and the blood and urine smeared his legs

and he ascended bodily unto heaven,

and on the third day he rose into glory, which

is what we see here, the Piss Christ in glowing blood:

the whole irreducible point of the faith,

God thrown in human waste, submerged and shining.

We have grown used to beauty without horror.

We have grown used to useless beauty.

Adorno on dismantling the affirmative lie of culture

A delightful morning spent meditating on two related thoughts from Theodor Adorno:

A delightful morning spent meditating on two related thoughts from Theodor Adorno:

‘The eclipse of art which is being propagated by people who are either just plain thoughtless or resentful of art would be false and would play into the hands of conformism. Desublimation – the instantaneous, immediate gratification which art is supposedly able to furnish – is of course beneath art in terms of intra-aesthetic standards. But even in terms of real libidinal gratification, desublimation has little to offer … The impoverished aestheticism that accompanies the sort of panting politics of the student movement is a complement of the general exhaustion of aesthetic vigour. To recommend the acceptance of jazz and rock-and-roll over Beethoven does nothing to dismantle the affirmative lie of culture. All it does is give the culture industry an excuse for more profit-taking and barbarity. The allegedly vigorous and uncorrupted essence of such products is in reality synthetically put together by the very powers that are the target of this supposed Great Refusal. They are worse than anything else’. – Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann; trans. C. Lenhardt; London/Boston/Melbourne/Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), 440–1.