By way of drawing a conclusion to a series of wee posts on exploring a theology of childhood (see previous posts on John Calvin, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Karl Barth, David Jensen, Karl Rahner and Tony Kelly) I turn here to German Reformed theologian Jürgen Moltmann. In his essay ‘Child and Childhood as Metaphors of Hope’ [Theology Today 56, no. 4 (2000), 592-603], Moltmann observes the difference in how parents or educators speak about the child, how a child speaks about herself, and how adults recall their own childhood. These three ways of speaking of childhood can also be referred to as (1) ‘pedagogical childhood’, (2) ‘child’s childhood’, and (3) ‘future childhood’.

By way of drawing a conclusion to a series of wee posts on exploring a theology of childhood (see previous posts on John Calvin, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Karl Barth, David Jensen, Karl Rahner and Tony Kelly) I turn here to German Reformed theologian Jürgen Moltmann. In his essay ‘Child and Childhood as Metaphors of Hope’ [Theology Today 56, no. 4 (2000), 592-603], Moltmann observes the difference in how parents or educators speak about the child, how a child speaks about herself, and how adults recall their own childhood. These three ways of speaking of childhood can also be referred to as (1) ‘pedagogical childhood’, (2) ‘child’s childhood’, and (3) ‘future childhood’.

1. A concerned parents and educators view of childhood.

From the view of concerned parents and teachers, childhood is an age that is meaningful and good in itself on the one hand; on the other hand, it is a stage that is to be overcome by the child’s own development, through training provided by adults and education provided by the society. Finally, parents have to bring up their children, so that they can become something and can be made fit for a life in the world of adults … The open future of children has been pressed into the prescribed adult world through parental and educational measures. Childhood has been viewed as the ‘evolving’ stage of human existence, while old age seems to be the ‘devolving-stage of human existence’. The model of full humanity thus has been the grown-up human being between the ages of twenty-five and sixty-preferably, of course, the ubiquitous man ‘in his best years’.

Moltmann proceeds to cite the work of Leopold von Ranke to sponsor his protest against those notions which would reduce childhood to a mere ‘underdeveloped stage that must be overcome’, or, in von Ranke’s words, as a ‘prologue of the future’, claiming that

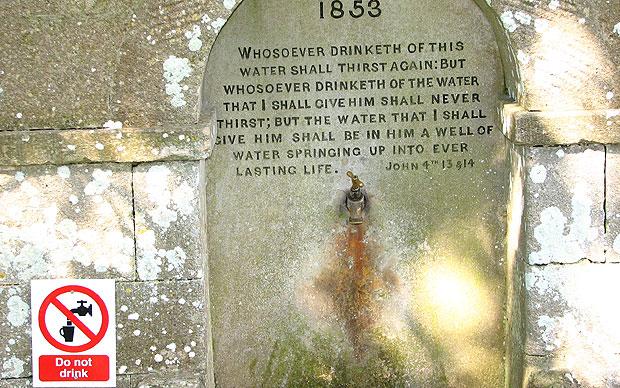

‘every epoch is immediate to God’, since the Divine strives to manifest itself in every epoch, and cannot be manifest in its entirety in any one single age. The same is valid for the stages of human life. Children, adolescents, adults and seniors find meaning in each stage of their lives. Every lived moment has meaning for eternity and represents ‘life in abundance’. Thus, every child and youth has a ‘right to their own present’. Even a child who dies early could have had an ‘abundant’ life. Life in abundance is not measured in terms of length, but in terms of the depth of life experience, a quality that will never be reached by a mere quantity of years lived and time spent. Life that is abundant in every present moment has to be affirmed and respected by others, by parents and educators, and should not be sacrificed on the altar of progress.

2. A child’s view of childhood.

2. A child’s view of childhood.

How children view childhood is an almost impossible mystery for adults to discern. Moltmann writes:

What childhood is for children or how children view their own childhood remains a mystery almost impossible for adults to access since our experiences get confused with both our desires and fears … Perhaps we only become conscious of our childhood experience when we are no longer children, since we can only recognize that from which we are already removed. I think that childhood is outlined and determined by the fact that we are no longer ‘in the safety’ of our mother’s womb, but not yet ‘independent’ … On the other hand, we recall the dependencies, the nightly fears, the powerless dreams of one’s own all-powerfulness and the empty days. We also call to mind how small we were and how big the father, how helpless we were and how omniscient our mother, as well as how the bigger children always seemed already capable of everything. And still we experienced and performed everything ‘for the first time’. With boundless amazement, we would follow the flight of a fly and would interrogate our parents with unanswerable questions of ‘why’. How entranced we were in our games, reacting spontaneously and with unpremeditated laughter and tears. The darkness of the lived moment” would often be very dark and would not become light, either before or after. Surely before we were ‘school children’, we were ‘playing children’ but even then we were watched by adults and we adopted their attitudes and opinions in order to please them. Still, we will have to find some way to respect the interior perspectives of a child’s experience: otherwise all of our analyses read our own projections onto the child.

3. An adult’s view of their childhood or the child in themselves.

3. An adult’s view of their childhood or the child in themselves.

Moltmann names the sentimentality and regressiveness that keep us from making peace with the reality of our own aging, when our ‘beginning gets glorified’ and ‘childhood is retrospectively seen as a landscape of unlimited possibilities and objectified as the potential of beginning’. He continues:

Since there is always more in our beginnings than we can actually bring forth, given the complexity of our circumstances, childhood and youth come to be seen as the glorified dawn of life. When we think of our youth and of all we might have been, we discover the future in our past. Our past ‘beginnings’ become the source of our future, in such a way that a ‘future childhood’ is constructed. This childhood awakens deep longings inside of us: the longing to be secure, to feel warm; the longing to experience life as a mystery one more time, the longing to experience wonder; the longing for a new beginning; a longing for the child within that wants to be born anew, so that the miracle of life may begin yet again. From this perspective, the beginnings of life seem pure and good. Consequently, children always seem innocent to us: their eyes mirror dreamy innocence. Yet, when is it that humans become capable of guilt? The dream of a sexually innocent childhood may only be the reversal of the old, terrible doctrine of original sin, which taught that children were conceived and born in sin and therefore had to grow tip under humanity’s hereditary burden. But from this perspective of ‘future childhood’, ‘innocence’, ‘new beginning’, and access to a ‘world of unlimited possibilities’, we construct childhood as a metaphor of hope.

‘In order to have vision we must have memory. Indeed forgetfulness or amnesia is precisely what strips us of vision – without the past there can be no future. So our contemporary improvisation must be informed and directed by both a profound indwelling of the biblical vision of life and a discerning attentiveness to the postbiblical scenes that have already been acted out in the history of the church.

‘In order to have vision we must have memory. Indeed forgetfulness or amnesia is precisely what strips us of vision – without the past there can be no future. So our contemporary improvisation must be informed and directed by both a profound indwelling of the biblical vision of life and a discerning attentiveness to the postbiblical scenes that have already been acted out in the history of the church.