William Willimon recently posted an exceptional series of posts in the form of ‘advice’ for those starting in pastoral ministry. It is taken from a book edited by Allan Hugh Cole titled From Midterms to Ministry: Practical Theologians on Pastoral Beginnings. I have pasted Bishop Willimon’s posts together into this one post. Read on seminarians, pastors and theological educators, and be encouraged … and challenged. This is one to keep coming back to and re-reading again, and again.

Between Two Worlds

In retrospect, my first year as a pastor was perhaps the most painful, frightening year of my entire ministry. Part of the terror that I experienced was my fear of failure, not simply to fail at being an effective pastor (I had little means of knowing what being “effective” would look like), but rather my fear that I had failed to discern God’s will for my life. What I had thought was my tortured, gradually dawning, wrestling with “call to the ministry,” might be revealed as something other than God’s idea. Looking back, I realize now that the early bumps and potholes that I experienced during the course of that first year were so disconcerting because each one of them made me wonder: maybe my friends are right. Maybe I don’t have what it takes to be a pastor. Perhaps the church really is a waste of my life.

As it turned out, I received more confirmation of my vocation in that first year than invalidation. Wonder of wonders, God really did occasionally speak through me to God’s people, God really did sometimes use me to work a wonder, and God’s people – some of them – really did respond to my ministry. I came to realize that much of my consternation was due, not to my own lack of preparation, or to inadequacies in me or in the church but rather to a move I was making from one world to another.

I recently heard Marcus Borg of the errant “Jesus Seminar” chide us pastors for protecting our congregations from the glorious fruits of “contemporary biblical scholarship.” There’s a brave new world of insight through the historical-critical study of Scripture! Don’t hold back from giving the people in the pew the real truth about Jesus as it has been uncovered by contemporary biblical scholarship and faithfully delivered to you in seminary biblical courses. He implied that even the laity, in their intellectual limitations, can take the truth about Jesus as revealed by Professor Borg and his academic friends.

Yet it seemed not to occur to Professor Borg that contemporary biblical scholarship, because it is asking the wrong questions of the biblical texts, and even more because it is subservient to a community that is at odds with communities of faith, may simply be irrelevant both to the church and to the intent of the church’s Scripture. Sometimes the dissonance between the church and the academy is due, not to the benighted nature of the church, but rather to the limited thought that reigns in the academy.

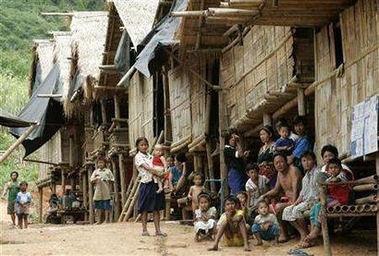

It took me a long time to learn this. As I said, I remember experiencing that dissonance in my first days in my first church in rural Georgia. I was the freshly minted product of Yale Divinity School now forlorn and forsaken in a poor little parish in rural Georgia. My first surprise was how difficult it was to communicate. If was as if I were speaking a different language. As I preached, my congregation impassively looked at me across a seemingly unbridgeable gulf.

At first I figured that the problem was a gap in education. (Educated people are continued to think this way when dealing with the uneducated.) I had nineteen years of formal education behind me; many of them had less than twelve. Most of my education involved lots of writing and talking, whereas they seemed taciturn and reserved.

I was impressed that they knew more about some things than I. Mostly, they talked and thought with the Bible. They easily, quite naturally referred to Scripture in their conversation, freely using biblical metaphors, sometime referring to obscure biblical texts that I had never read. If they had not read the masters of my thought – Bultmann, Tillich, and Barth, then I had no way to speak to them. I had been in a world that based communicating upon conversations about the thought of others, rather than worrying overmuch about my own thoughts. I realized that my divinity school had made me adept in construing the world psychologically, sociologically (that is, anthropologically) rather than theologically. The only conceptual equipment my people had was that provided by the church, whereas most of my means of making sense were given to me by the academy. Their interpretation of the world was not simply primitive, or simple, or naïve, as I first thought. Rather they were thinking in ways that were different from my ways of thinking. I came to realize that we were not simply speaking from different perspectives and experiences; it was as if we were speaking across the boundaries of two different worlds.

When a theologically trained seminary graduate like me confronts the sociological reality of the church, when a new pastor, schooled in a vision of the church as it ought to be, has his or her nose rubbed in the church as it is, it’s a collision that is the concern of this book. The leap between academia and ecclesia can be a challenge.

I want to avoid a characterization of the challenge as a leap between the goofy ideal (ecclesia as portrayed in the thoughtful academy) and the gritty real (ecclesia as it is in all its grubby mediocrity). Sometimes new pastors say, “Seminary did not prepare me for the true work of ministry,” or “There is too great a gap between what I was told in seminary and what the church really is.”

I do not want to put the matter in a way that privileges academia over ecclesia, as if to imply that to theological schools and seminaries has been given the noble vision of the real, true, faithful church whereas it has been given to the church the grubby, impossible task of actually being the church, putting all that high falutin’ theological theory into institutional praxis.

The challenge is not to stretch oneself between the ideal and the real, or the clash between the theoretical and the practical, the challenge is in finding oneself in the middle of an intersection where two intellectual worlds collide. True, there is often a disconcerting disconnect between the questions being raised in the seminary and the answers that constitute the church. Yet there may also be the problem that the seminary is preoccupied with the wrong questions, or at least questions that arise from intentions other than the Kingdom of God and its fullness.

The Seminary’s World

To be sure, it’s risky to attempt to characterize so complex and diverse a phenomenon as “the seminary.” My characterization arises out of nearly thirty years on a mainline protestant seminary faculty and visits, in the course of time, to over forty different theological schools. Some of my books have become standard texts in the curriculum of a few dozen seminaries, so I know at least a large part of the world of the seminary.

I am helped, in attempting to generalize about theological education, because the world of the seminary is more uniform and standardized than the world of the church. Seminaries, be they large or small, conservative or liberal, have more in common than the churches they serve. They have patterned their internal lives, constructed their curricula, selected their faculties, and have expectations of their students that are based more on the models of other seminaries than on the mission of the church. That’s only one of the problems of theological schools.

Seminaries, at least those in our church, labor under a growing disconnect between the graduates they are producing and the leadership needs of the churches these graduates are serving. This disjunction causes friction in and sometimes defeat of the transition between seminary and church for new pastors. For example, most protestant seminaries have organized themselves on the basis of modern, Western ways of knowing. The epistemology that still holds theological education captive is that which was borrowed from the modern university – detached objectively, the fact/value dichotomy, the separation of emotion and reason with the exaltation of reason as the superior means of knowing, the sovereignty of subjectivity, the loss of any authority other than the isolated, sovereign self pared with subservience to the social, cultural, and political needs of the modern nation state. (The best history of what happened in our seminaries in the Twentieth Century is by Conrad Cherry, Hurrying Toward Zion: Universities, Divinity Schools and American Protestantism, Indiana University Press, 1995.)

That’s saying a mouthful but it is an attempt to depict the intellectual “world” of the theological school that has a tough time honoring the intellectual restrictions of academia and the peculiarly sweeping mandate of the church of Jesus Christ.

The word “seminary” means literally “seed bed.” Seminary was meant to be the nursery where budding theologians are cultivated and seeds are planted that will bear good fruit, God willing, in the future. Trouble is, seminaries thought they could simply overlay those governmentally patronized, culturally confirmed ways of academic thinking over the church’s ways of thought, and proceed right along as if nothing had happened between the seminary as the church created it to be (a place to equip and form new pastoral leaders for the church) and the seminary as it became (another graduate/professional school).

In the world of the contemporary theological school, faculty talk mostly to one another (As Nietzsche noted, long ago, no one reads theologians except for other theologians.), faculty accredit and tenure other faculty using criteria derived mainly from the modern, secular research university. While the seminary desperately needs faculty who are adept at negotiating the tension between ecclesia and academia, faculty tend to be best at bedding down in academia. The AAR (American Academy of Religion) owns theological education.

One last disconnect I’ll mention: The seminary, by its nature, is a selective, elitist institution, selecting and evaluating its students with criteria that are derived from educational institutions rather than the ecclesia. In one sense, a theological school should be selective, astutely selecting these students who can most benefit Christ’s future work with the church. Trouble is, when criteria are applied that arise from sources other than the Body of Christ, we have the phenomenon of the church’s leadership schools cranking out people who have little interest in equipment for service to the church as it is called to be. If college departments of Religious Studies were not in decline, there would be something to do with the best of these seminary graduates. If the US Post Office were not holding its employees more accountable for their performance, the rest of them would have promising careers.

For instance, when my District Superintendents and I interviewed a group of soon to be graduates in one of our seminaries, we were distinctly unimpressed with their responses. Here we were before them saying, in effect, “We are a declining organization. We are looking for people who will come into the United Methodist ministry, take some risks, attempt to grow some new churches and new ministries, and help lead us out of our current malaise.” Yet the seminarians we were conversing with struck us as mostly those interested in being care givers to established congregations, caretakers of ministries that someone else long before them had initiated, and in general, to be people who were attracted to our church’s ministry precisely because they would never, ever have to take a risk with Jesus.

When I was critical of the students we were meeting, one of the pastors with me said, “Look, you have people who have spent a lifetime in school learning nothing more than how to be in school. They have been taught by tenured faculty who have given their lives to doing well in academia and thereby getting tenure and never having again to take a risk in their lives. Faculty who are not held accountable for their performance or results are not likely to educate clergy who are focused on accountability or results.”

When seminaries appoint faculty who have little skill or inclination to traffic between academia and church, is there any wonder why the products of their teaching find that transition to be so difficult? Alas, what many graduates do is quickly to jettison “all that theology stuff” that seminary attempted to teach and relent to the “real world” of the congregation, the rest of their ministry simply flying by the seat of their pants. The seminary may self-flatteringly think of itself as the vanguard of the thought of the church when in reality it is an agent for the preservation of the church’s boring status quo.

The Church’s World

Seminarians who have been schooled in modern, Western notions that they are primarily individuals, detached persons whose main source of authority is their own subjectivity, have thereby been inculcated into the unchristian notion that they should think for themselves. What a shock to enter their first parish and find that church is an essentially group phenomenon, an inherently traditioned enterprise. Our most original thinking occurs when we think, not by ourselves, but with the saints. The best thing that seminary has done for its graduates, if it has done its work, is to introduce them to the burden and the blessing of the church’s tradition, to form them into advocates for the collective witness of the church, and to make believe that the church is God’s answer to what’s wrong with the world. Yet the way that the seminary engages the witness of the saints makes it difficult for new pastors to think with the saints.

For example, Scripture, the tradition of the church, has a privileged place in the communication of the church. Pastors are ordained, ordered to bear that tradition compellingly, faithfully, quite unoriginally before their congregations, not primarily so that their congregations can think through the tradition, but rather so that they can, in their discipleship incarnate Christian truth. We pastors are not free to rummage about in the recesses of our own egos, not free to consult other extraecclesial texts until we have first done business with Scripture and the great tradition. Alas, too much of today’s theological training (arising out of the German university of the Nineteenth Century) places the modern reader above the texts of the church, assuming a privileged, detached and superior position to the church’s historic faith. The academic guild stands in judgment upon the texts, raising questions about the texts. Thus it comes as a jolt for the seminarian to graduate and to find him or herself cast in the role of the ordained, the official who leads the church not in detached criticism of these texts but rather in faithful embodiment of the sacred texts.

In my book, Pastor: The Theology and Practice of Ordained Ministry (Abingdon, 2002), I observed that many seminarians tend to be introverted, reflective, personal seekers after God whereas the church is heavily politicized and communal. Pastors are supremely “community persons,” officials of an institution, leaders who the church expects to worry about community and group cohesion with a Savior whose salvation is always a group phenomenon. The seminarian who is trained occasionally to write a speech for a group of individuals, sometimes to do one-on-one counseling, to form intense personal relationships within a conglomerate of individuals, finds herself flung into a politically charged, complex organization, a family system that requires astute knowledge of group dynamics and wise leadership of a divisive group of people who have been caught in the dragnet of God’s expansive grace in Christ. When Chrysostom argued his own inadequacy to be a pastor or bishop, it was precisely this public quality of Christian leadership that he cited as the reason why he did not have what it takes to be a pastor.

Sadly, too often the seminary has taught its students to step back from the Christian tradition and its Scriptures, to reflect, learn to critique, and actively to question. True, such stepping back and critique are developmentally appropriate for the formation of the church’s leaders. Yet when the seminarian becomes a pastor, she takes her place as leader of an organization that has goals like embodiment, engagement, involvement, participation, and full-hearted commitment, embrace of the enemy, hospitality to the stranger, group cohesion, koinonia. The whole point of discipleship is not cool consideration of Jesus but rather following Jesus. The person who fails to make the move from being the lone individual, confronting the faith, tending his or her own spiritual garden, to the role of a public leader of a group, is the person who will have a tough time in the first parish.

Today many describe the ordained ministry as “servant leadership.” The peculiar service that the church needs from those who ordained is that they step up, lay aside their own spiritual quandaries, and speak for the church to the church. They must, as the bishop tells them in the ordinal, “take authority,” cultivating in themselves the habit of thinking more about the community and its needs than their own. Students who have been enculturated into the world of the academy – in which students must defer and submit to the authority of the professor, who has submitted to the authority of the academic guild – sometimes have difficulty standing up in a congregation and, in service to the community, taking charge, casting a vision, and taking the time and doing the work to build a group of allies who will join the pastor in moving toward responsibility for Christ’s mission into the world.

I, therefore, say to seminarians, upon their graduation, you are not just taking on a new job, you are moving to a new world.

Recently, I asked a group of our best and brightest new pastors what they would like most from the church and from me as their bishop. I was surprised to hear them all respond: “Supervision!” They yearn for help with the move between these two worlds because they realize the inadequacy of their preparation. Churches and judicatories must take this move more seriously and must develop better means of mentoring and supervising new pastors through this process.

As someone who now works with new pastors on that move from the world of the theological school to the world of the parish, I have some specific suggestions:

1. Devise ways to learn to speak their language. Laity sometimes complain that their young pastor, in sermons, uses “religious” words like “spiritual practice,” “liberation,” “empowerment,” “intentional community” (this is an actual list a layperson collected and sent to me) that no one understands and no one recalls having heard in Scripture. Such “preacher talk” makes the pastor seem detached, alien, and aloof from the people and hinders leadership.

2. At the same time, prepare yourself to become a teacher of the church’s peculiar speech to a people who may have forgotten how to use it. This may seem contrary to my first suggestion. My friend, Stanley Hauerwas, says that the best preparation for being a pastor today is previously to have taught high school French. The skills required to drill French verbs into the heads of adolescents are the skills that pastors need to teach our people how to speak the gospel. Trouble is, most seminarians are more skilled, upon graduation from school, to be able to describe the world anthropologically than theologically. They have learned to use the language of Marxist analysis or feminist criticism better than the language of Zion. We must be person who lovingly cultivate and actively use the church’s peculiar speech.

3. Keep telling yourself that the difference in thought between the laity in your first parish and that of your friends back in seminary is not so much the difference between ignorance and intelligence; it’s just different ways of thinking that arise out of life in different worlds. I recommend reading novels (Flannery O’Connor saved me in my first parish by writing true stories that sounded like they were written by one of my parishioners) in order to appreciate the thought and the speech of people who, while having never been initiated into the narrow confines of the world of theological education, are thinking deeply.

4. Remind yourself that while the seminary has an important role to play in the life of the church, it is the seminary that must be accountable to the church, not vice versa. It is my prejudice that, if you have difficulty making the transition from seminary to parish it is probably a criticism of the seminary. The Christian faith is to be studied and critically examined only for the purpose of its embodiment. Christians are those who are to become that which we profess. The purpose of theological discernment is not to devise something that is interesting to say to the modern world but rather to rock the modern world with the church’s demonstration that Jesus Christ is Lord and all other little lordlets are not.

5. Be open to the possibility that the matters that were focused upon in the course of the seminary curriculum, the questions raised and the arguments engaged, might be a distraction from the true, historic mission and purpose of the church and its ministry.

6. On the other hand, be open to the possibility that the church has a tendency to bed down with mediocrity, to accept the mere status quo as the norm, and to let itself off the theological hook too easily. One reason why the church needs theology explored and taught in its seminaries is that theology (at its best) keeps making Christian discipleship as hard as it ought to be. Theology keeps guard over the church’s peculiar speech and the church’s distinctive mission. Something there is within any accommodated, compromised church (and aren’t they all, in one way or another?) that needs to reassure itself, “All that academic, intellectual, theological stuff is bunk and is irrelevant to the way the church really is.” The way the church “really is” is faithless, mistaken, cowardly, and compromised. It’s sad that it is up to seminaries to offer some of the most trenc hant and interesting critiques of the church. Criticism of the church ought to be part of the ongoing mission of a faithful church that takes Jesus more seriously and itself a little less so. I pray that your theological education rendered you permanently uneasy with the church. Promise me that you will, throughout your ministry, never be happy with the church.

7. I pray that you studied hard in seminary, read widely, thought deeply because you are going to need all of that if you are going to stay long as a leader of the church. Your life would be infinitely easier and less complicated if God had called you to be an accountant or a seminary professor. Most of the stuff that you read in seminary will only prepare you really to grow and to develop after you leave seminary. Think of your tough transition into the parish as the beginning, not the end, of your adventure into real growth as a minister. Theology tends to be wasted on the young. It’s only when you run into a complete dead end in the parish, when you are aging and tired and fed up with the people of God (and maybe even God too) that you need to know where to go to have a good conversation with some saint in order to make it through the night. Believe it or not, it’s much easier to beg in in the ministry, even considering the tough transition between seminary and the parish, than it is to continue in ministry. A winning smile, a pleasing personality, a winsome way with people, none of these are enough to keep you working with Jesus, preaching the Word, nurturing the flock, looking for the lost. Only God can do that and a major way God does that is through the prayerful, intense reading, study and reflection that you can only begin in three or four years of seminary.

8. Try not to listen to your parishioners when they attempt to use you to weasel out of the claims of Christ. Much of the criticism that you will receive, many of their negative comments about your work, are just their attempt to excuse themselves from discipleship. “When you are older, you will understand,” they told me as a young pastor. “You have still got all that theological stuff in you from seminary. Eventually, you’ll learn,” said older, cynical pastors. Now it’s, “Because you are a bishop, you don’t really understand that I can’t….” God has called you to preach and to live the gospel before them and they will use any means to avoid it. Be suspicious when people encourage you to see the transition from seminary to the parish as mainly a time finally to settle in and make peace with the “real world.” Jesus Christ is our definition of what’s real and there is much that passes for “the way things are” in the average church that makes Jesus want to grab a whip in hand and clean house.

9. The next few years could be among the most important in your ministry, including the years that you spent in seminary, because they are the years in which you will form your habits that will make your ministry. That’s one reason why I think the Lutherans are wise to require an internship year in a parish, before seminary graduation, for their pastors and why I think that a great way to begin is to begin your ministry is as someone’s associate in a team ministry in a larger church. In a small, rural church, alone, with total responsibility in your shoulders, in the weekly treadmill of sermons and pastoral care, if you are not careful there is too little time to read and reflect, too little time to prepare your first sermons, so you develop bad habits of flying by the seat of your pants, taking short cuts, and borrowing from others what ought to be developed in the workshop of your own soul. Ministry has a wa y of coming at you, of jerking you around from here to there, so you need to take charge of your time, prioritize your work, and be sure that you don’t neglect the absolute essentials while you are doing the merely important. If you don’t define your ministry on the basis of your theological commitments, the parish has a way of defining your ministry on the basis of their selfish preoccupations and that is why so many clergy are so harried and tired today. Mind your habits.

The Necessity of Mentors

One of the most important decisions that a new pastor can make is to obtain a good pastoral mentor. Ministry is a craft. I am unperturbed when new pastors sometimes say, “Seminary never really taught me actually how to do ministry.” I think seminary is best when it instills the classical theological disciplines and exposes to the classical theological resources of the church, not so good at teaching the everyday, practical, administrative and mundane tasks of the parish ministry. One learns a craft, not by reading books, but by looking over the shoulder of a master, watching the moves, learning by example, developing a critical approach that constantly evaluates and gains new skills.

Selecting a mentor can be your greatest challenge as a new pastor. Few experienced pastors have the training or the gifts for mentoring a new colleague. The “Lone Ranger” mentality afflicts many lonely pastors and their work shows the results of their failure to obey Jesus’ sending of the Seventy “two by two” (Luke 10:1). Some senior colleagues are often threatened by your youth, or your idealism, or your talent, seeing their own failures and disappointments in the light of your future promise. You will encounter those experienced pastors whose main experience has been that of accommodation, appeasement, and disillusionment with the meager impact of their ministry. They have a personal stake in robbing you of your youthful energy and expectation for ministry. Their goal is to get you to say, “Well, I thought that ministry in the name of Jesus would be a great advent ure but now I’ve settled in and turned it into a modestly well paying job.”

Yet in asking someone to be your mentor, to look into your life, to show you how to do ministry as they have done it, is one of the most flattering and affirming things you can do for a senior colleague. The Christian ministry is too tough to be done alone. There is something built into the practice of Christian ministry that requires apprenticeship from Paul mentoring young Timothy to Ambrose guiding the willful Augustine, to Carlyle Marney putting his arm around me and saying, “Here’s what a kid like you has got to watch out for.” In my experience, one of the most revealing questions that I can ask a new pastor is, “Who are your models for ministry? Whose example are you following?”

One of the most decisive examples given to me, in my first months of ministry, was a negative one. I was attending my first Annual Conference. Between one of the sessions, an older, self-presumed wiser pastor took me aside and said, “Son, you seem ambitious and talented. Let me give you some advice that I wish someone had given me when I was at your age. Buy property at Junaluska (Lake Junaluska, the retreat center now Methodist resort near our Conference).”

Property at Junaluska?” I asked in wide-eyed stupidity.

“Right. Doesn’t have to be a house. Perhaps start with an undeveloped lot. Eventually move up to a home at Junaluska,” he continued. “Name me one person on the Bishop’s Cabinet who doesn’t have a house at Junaluska,” he responded before moving on to offer advice to some other promising young pastor.

I thought to myself, “Four years of college. Three years of seminary. Three years of graduate school for the purpose of a lousy mortgage at Lake Junaluska. This is what it’s all about?”

That interchange was one of the most significant in my first days as a United Methodist minister. It was encouragement for me to lay hold of the vocation that had taken hold of me. Standing there in the lobby of the auditorium, I prayed, “Lord, you have my permission to strike me dead if I ever degrade my vocation as that guy has degraded his.”

That I am here today, over thirty years after my transition from seminary to the pastoral ministry, writing this essay, suggests to me that I kept the solemn vow I made that day. More likely is that the Lord is infinite in mercy, full of forgiveness, and patient with those whom the Lord calls to ministry.

William H. Willimon

![Andreas Serrano - Piss Christ [1987] Andreas Serrano - Piss Christ [1987]](https://jasongoroncy.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/andreas-serrano-piss-christ-1987.jpg?w=940)