Rick Floyd is a seasoned minister and a very astute theologian who has posted a wonderful and wise reflection on pastoral ministry for ‘newly-minted ministers’. I appreciated it so much that I’m going to re-post it here in its entirety. I reckon that there’s wisdom here that needs to be shared.

‘Too many of our new pastors in the mainline church leave the ministry after a few years. There are many reasons why this happens, but for whatever reason, it is not good. It’s bad for them and bad for the church, and it is bad stewardship to train someone who only serves a short time.

Some of these ministers should never have been ordained in the first place, and the gatekeepers didn’t do their due diligence. Some were lacking the necessary “gifts and graces” for ordained ministry, which doesn’t mean they didn’t have a different and effective ministry in the church.

There are far too many sad situations where a ministry fails for one reason or another, where hopes are shattered, and a young (or not so young) person is saddled with a financially crippling debt for the years in seminary they paid for in loans.

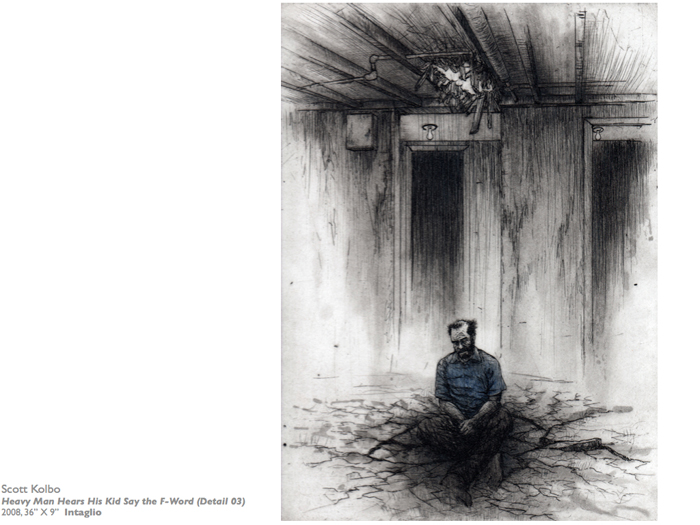

Being a pastor of a church is a hard job. I was one for thirty years. Despite the nonsense being promulgated by the “experts,” faithful pastoring is not a matter of working a certain number of hours (or “units” as they are now sometimes called.) It’s a vocation that takes up most of your waking hours,

When a congregant really needs you, it doesn’t matter whether it is your day off. If you asked me how many seasoned pastors are burned out to one degree or another, I would say, “All of them, if they are really doing their job.” That is why pastors need to exercise radical self-care, pray constantly, and accept the fact, that not being yourself God, you cannot do all that is demanded of you.

Now I readily admit that there is some truth to the whole boundary/take care of yourself/take time for yourself movement. But like all partial truths it is not the whole truth. The church once had a useful word, now much out of favor, for when one piece of the truth gets blown out of proportion. The word is heresy.

One of the modern heresies (but by no means the only one) of the contemporary mainline church, is that you can have something akin to a normal 40 hour a week professional life and be a faithful pastor. It isn’t true. A pastor’s life, and the life of the pastor’s family is necessarily involved in the community of their congregation in season and out of season. Sometimes, even often, it is wonderful; other times it isn’t. That’s the way it goes. It isn’t the Canyon Ranch spa. I often say being a pastor is the best vocation there is, but perhaps the worst job. If you are not called to it, it is something you really don’t want to do.

When I started as a pastor thirty-five years ago I was well trained and well educated and didn’t have a clue what I was really supposed to do. I learned quickly. One of the things I learned was that you have to love your congregants, even the unlovable, of which there are far too many, and who take up a good deal of your time. If and when you find yourself loving them, you know you are on your way to really being a pastor. Some of them you will just never learn to love, and you have to turn them over to God, who does.

I had been a anti-war and civil rights activist in college and seminary, and had gone to jail for my causes, but when I got into the pastorate I learned very quickly that you can’t be a prophet until you have earned the peoples’ trust. This means years of marrying and burying and sitting by sick beds and in hospital rooms.

I had been a anti-war and civil rights activist in college and seminary, and had gone to jail for my causes, but when I got into the pastorate I learned very quickly that you can’t be a prophet until you have earned the peoples’ trust. This means years of marrying and burying and sitting by sick beds and in hospital rooms.

If you do this well they may be ready to hear hard truths from the pulpit. They may not. Certainly Isaiah’s prophecies fell on deaf ears.

New ministers who have grown up in the church have a leg up, because they know its rhythms and customs, it’s “grandeur and misery.”

But today many of our ministerial candidates haven’t grown up in the church. Some of them turn out to be our best ones, but they are at a disadvantage. They don’t know the church’s music and it’s well-worn liturgies. They don’t know the joys of a community strawberry festival on a warm spring day, or the energy and agony of a capital-funds campaign to get a new boiler.

They often come to seminary or divinity school in a process of self-discovery, which is fine. Most of us did that to one degree or another. I recall from seminary that the ones who knew they wanted to be a minster since the age of six were best avoided, and probably needed therapy.

Now seminary is a good place to learn many useful things, like that David didn’t write all (or perhaps any) of the Psalms, that the Scriptures are thick and have a literary history, and that the heresies we see around us are as old as the church. If one is lucky, you’ll find a mentor or two, and be able to intern in a healthy church who will love you and teach you what it means to be the church.

What seminaries are not good at (because its not really their job) is forming men and women into Christians, much less teach them how to be faithful pastors. Christian formation is primarily the church’s job, not the schools, although they can help out.

There are many fine teachers and students in these schools, and I don’t want in any way to impugn their integrity or their faith.

At the same time, we are seeing too many newly-minted pastors who come to seminary, not only to find themselves, but with a passion for a social cause or causes, which is fine. I certainly had mine. In seminary the flame of their passion is often fanned by others who share it, which is also fine.

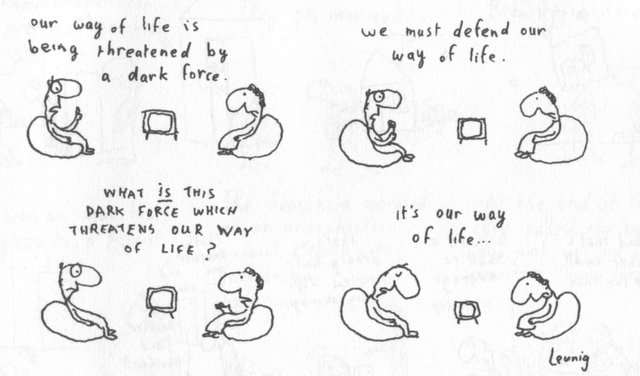

But if all you know of the faith is what you learn in divinity school you are at a distinct dis-advantage. And if the main reason you accept a call from a congregation is to promote your passion and cause then your soul is in danger, and so is the life of a congregation.

Because the congregation you go to may or may not share your passions. It can be dangerous either way.

If they agree with most of your views, be they liberal or conservative, the temptation is to self-justification and self-righteousness, and a tendency to see sin and evil as “out there” in your ideological adversaries, and not also in your own heart and soul. Then the great insight expressed by the Reformers’ axiom simul justus et peccator, that we are at the same time justified and sinners, is lost. This danger in the mainline church can exist in some ministers for their entire careers and they will never even now it.

The other temptation is perhaps more dangerous, at least in mainline churches. That is to go to your first congregation where they don’t share your passion for your social cause or causes, and you scold them for it. You do not learn to love them, and they do not learn to love you, and eventually your ministry fails.

Typically we are too polite to ever actually fire anyone (although it does happen), but there are other ways to get you to leave, the best one being to so discourage you that you lose heart and leave. Some, too many, of our new pastors actually seek out this kind of martyrdom, and when they are inevitably cast out, they can then turn and say how stiff-necked and hard-hearted their congregation was. But my sympathy for them is limited. Congregations can be stiff-necked and hard-hearted and even abusive. This is nothing new. Just go read Exodus or First Corinthians.

Typically we are too polite to ever actually fire anyone (although it does happen), but there are other ways to get you to leave, the best one being to so discourage you that you lose heart and leave. Some, too many, of our new pastors actually seek out this kind of martyrdom, and when they are inevitably cast out, they can then turn and say how stiff-necked and hard-hearted their congregation was. But my sympathy for them is limited. Congregations can be stiff-necked and hard-hearted and even abusive. This is nothing new. Just go read Exodus or First Corinthians.

But congregations can be also be wonderful, supportive, gracious, and long-suffering, especially if they sense you are really trying to be their faithful pastor.

The late great Bill Coffin, a prophet himself, once told a bunch of us young ministers (about 1972) a story (which my version here will be only a loose approximation) about one of his students from Yale.

The young pastor was in hot water for his deeply prophetic views and fiery pulpit pronouncements on social issues (it was Vietnam time, and the nation was deeply divided.) The lay leaders wanted to fire him. As the discussion heated up, one of them, a banker, prominent member and very conservative, stood up and said, “You can’t fire him, he’s our pastor. It’s true that he’s a real pinko, and I can’t stand most of the stuff he says from the pulpit, but when my wife was dying he came to see her every day. He’s staying.” And he did. Bill went on to say that if you are a faithful pastor, your flock will give you great freedom to pursue your passions, be it peace and justice work, or collecting butterflies.

A dear rabbi friend of mine who is well up in his eighties told a bunch of us a powerful story last week. He had been an army chaplain in the Korean War, and, perhaps because of that, he was a firm supporter of the Vietnam War. But when our National Guard opened fire and killed some students who were peacefully protesting the war at Kent State University in 1970, he had a change of heart, and he changed his mind. And on the next High Holy Days in the fall, when he preached to the biggest congregation of the year, he apologized to them and asked them to forgive him, admitting that he had been wrong about the war. This story brought tears to my eyes.

He had been their faithful rabbi by then for fifteen years, and he stayed for another dozen or so. The Vietnam War by 1970 was very unpopular, especially here in what until last December was sometimes called by conservatives “The Peoples Republic of Massachusetts.” I am sure that many of his congregants had been hearing sermons they didn’t agree with for some time. But he had earned the right. And when he finally repented publicly, he was indeed a prophet with the full attention of his people. From then on, when he spoke out against the war, he had every ear.

So at the right time and place you can sometimes be both a prophet and a pastor. But you’d better be a pastor to the people first, because that is your primary calling. If you just want to be a prophet, I suggest you go work for a political action organization’.