Those hunting for some liturgical resources for Ash Wednesday services may like to check out a few poems, prayers and links that I posted here last year.

Author: Jason Goroncy

Introducing young readers to Olympia Morata

Simonetta Carr has established herself as one with something of a vocation to introduce children and teenagers to some of the heroes of the Church. She has so far penned delightful and informative children’s books on Athanasius, Augustine, John Calvin and John Owen (as part of the ‘Christian Biographies for Young Readers’ series published by Reformation Heritage Books and aimed at children from 7 to 10 years of age). In her latest book, a fictionalised biography titled Weight of a Flame (P&R Publishing, 2011) she introduces ‘young readers’ (read teenagers) to the inspiring ‘Italian Heretic’ Olympia Morata (1526–1555), locating Morata in her social and religious context – a volatile sixteenth-century Europe – and highlighting her passion for Scripture, for Calvin’s Institutes, for scholarship (she lectured on Cicero, wrote commentaries on Homer, and was one of the most sophisticated Latin stylists of her time), for poetry, and for faith. Those seeking Morata for grown-ups should read Morata’s work first hand (published as The Complete Writings of an Italian Heretic and edited by Holt N. Parker) and the relevant chapter in Roland Bainton’s Women of the Reformation: In Germany and Italy. (There are also published studies by Jules Bonnet, Amelia Gillespie Smyth, Ottilie Wildermuth, Caroline Bowles Southey, Robert Turnbull.) But for Carr’s target audience, this book is the only one I know of on Morata. It’s just a pity that the book’s cover (by which all books are judged) is so suggestive of an advertising brochure for some exclusive and now-outdated ‘college for young, strong and self-reliant ladies’.

Simonetta Carr has established herself as one with something of a vocation to introduce children and teenagers to some of the heroes of the Church. She has so far penned delightful and informative children’s books on Athanasius, Augustine, John Calvin and John Owen (as part of the ‘Christian Biographies for Young Readers’ series published by Reformation Heritage Books and aimed at children from 7 to 10 years of age). In her latest book, a fictionalised biography titled Weight of a Flame (P&R Publishing, 2011) she introduces ‘young readers’ (read teenagers) to the inspiring ‘Italian Heretic’ Olympia Morata (1526–1555), locating Morata in her social and religious context – a volatile sixteenth-century Europe – and highlighting her passion for Scripture, for Calvin’s Institutes, for scholarship (she lectured on Cicero, wrote commentaries on Homer, and was one of the most sophisticated Latin stylists of her time), for poetry, and for faith. Those seeking Morata for grown-ups should read Morata’s work first hand (published as The Complete Writings of an Italian Heretic and edited by Holt N. Parker) and the relevant chapter in Roland Bainton’s Women of the Reformation: In Germany and Italy. (There are also published studies by Jules Bonnet, Amelia Gillespie Smyth, Ottilie Wildermuth, Caroline Bowles Southey, Robert Turnbull.) But for Carr’s target audience, this book is the only one I know of on Morata. It’s just a pity that the book’s cover (by which all books are judged) is so suggestive of an advertising brochure for some exclusive and now-outdated ‘college for young, strong and self-reliant ladies’.

Here’s a wee video of Simonetta introducing Weight of a Flame:

And another produced by the Boekestein kids (all under 7) after reading Simonetta’s book:

Eugene Peterson on Stories

‘Just as there is a basic human body (head, torso, two arms, two legs, etc.), so there is a basic story. All stories are different in detail (like all bodies) but the basic elements of story are always there. For the purposes of sharpening our recognition of and appreciation and respect for the essential narrative shape of Scripture, we need to distinguish only five elements.

‘Just as there is a basic human body (head, torso, two arms, two legs, etc.), so there is a basic story. All stories are different in detail (like all bodies) but the basic elements of story are always there. For the purposes of sharpening our recognition of and appreciation and respect for the essential narrative shape of Scripture, we need to distinguish only five elements.

First, there is a beginning and ending. All stories take place in time and are bounded by a past and a future. This large encompassing framework presumes both an original and a final goodness. We have an origin, way back somewhere, somehow, that is good (creation, Eden, Atlantis); we have a destination, someplace, sometime, that is good (promised land, heaven, utopia).

Second, a catastrophe has occurred. We are no longer in continuity with our good beginning. We have been separated from it by a disaster. We are also, of course, separated from our good end. We are, in other words, in the middle of a mess.

Third, salvation is plotted. Some faint memory reminds us that we were made for something better than this. Some faint hope lingers that we can do something about it. In the tension between the good origin and destiny and the present evil, a plan develops to get us out of the trouble we are in, to live better than we find ourselves, to arrive at our destination. This plan develops with two kinds of action, the battle and the journey: we must fight the forces that oppose our becoming whole; we must find our way through difficult and unfamiliar territory to our true home. The battle and journey motifs are usually intertwined. These battles and journeys are both interior (within the self) and exterior.

Fourth, characters develop. What people do is significant. Persons have names and dignity. They make decisions. Persons are not lead soldiers lined up and moved about arbitrarily; personalities develop in the course of the conflict and in the passage of the journey, character and circumstance in dynamic interplay with each other. Some persons become better; some become worse. Nobody stays the same.

Fifth, everything has significance. Since “story” implies “author,” nothing is in it by accident. Nothing is mere “filler.” Chekov once said that if a writer puts a gun on the table in the first chapter, somebody has to pull the trigger by the last chapter. Every word connects with every other word in the author’s mind, and so every detail, regardless of how it strikes us at first, belongs – and can be seen to belong if only we look long enough at it.

All the world’s stories have these characteristics. The five elements can be more or less implicit or explicit, but they are there. With variations in emphasis and proportion, with shifts of perspective and invention of detail, they develop into tragedies, comedies, epics, confessions, murder mysteries, and gothic romances. Poets, dramatists, novelists, children, and parents have developed millions of variations on these elements; some of them have been written down.

What was written down in the Bible is a huge, sprawling account that contains subject matter from several cultures, languages, and centuries. There are many things and people in it, written about in many different ways; but with all the seeming heterogeneity, it comes out as a story. Northrop Frye, coming at Scripture as a literary critic and not as a believer or theologian, in his careful study of it is convinced that this is its most important feature: “The emphasis on narrative, and the fact that the entire Bible is enclosed in a narrative framework, distinguishes the Bible from a good many other sacred books.”

The Bible’s basic story line is laid down in the Torah, the first five books. Creation is the good beginning, worked into our memories with the rhythmic repetitions, “and God saw that it was good.” The promised land is the good ending as Moses leads the people up to the border of Canaan and then leaves them with his Deuteronomy sermon ringing in their ears. In between is the catastrophe of the fall, succeeded by the plot of salvation worked out in pilgrimage – from Eden to Babel to Ur to Palestine to Egypt to wilderness to Jordan – and in fights with family, Egyptians, Amalekites, and Canaanites. Character development is shown in Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, and Moses in major ways, and in numerous others on a smaller scale. The significance of every detail of existence is emphasized by including genealogical tables, ceremonial regulations, social observations, and rules for diet.

This story is repeated in the Gospels. The virgin birth is the good beginning, the ascension the good end. Catastrophe erupts in the Herodian massacre and threatens in the wilderness temptations. The salvation plot is worked out on a journey from Galilee to Jerusalem and in conflict with devils, disease, Pharisees, and disciples. The person of Jesus is prominent in the story, with Peter, James, and John in strong supporting roles. Much care is given to the details of geography, chronology, and conversation: nothing escapes signification – not a sparrow, not a hair of our heads.

The same story is told with a tighter focus in Holy Week. The hosanna welcome launches the good beginning, the resurrection marks the good ending. Judas’s betrayal is the catastrophe. Salvation is plotted through the conflicts of trial, scourging, and crucifixion and on the journey from Bethany to upper room to Gethsemane to trial sites to Golgotha to the garden tomb. Jesus’ words and actions exhibit the working out of the life of redemption, everything that he says and does being presented as revelatory. No detail is without significance: Mary’s perfume, the centurions comment. The narrative that is explicit in Torah and Gospels is extended over the entire Scriptures by means of the canonical arrangement of the diverse books. The Hebrew canon is formed in three parts. The Torah (Genesis through Deuteronomy) sets down the basic story. The Prophets (Joshua through Malachi) take the basic story and introduce it into new situations across the centuries, insisting that it be believed and obeyed in the present, not merely recited out of the past. This involved a good deal of disruption and controversy. The Writings (Psalms through Chronicles) provide a reflective response to the story, assimilating and then responding to it in wisdom (Job and Proverbs) and in worship (Psalms).

The New Testament has a parallel shape. The Gospels tell the basic story in a new Torah. The Epistles correspond to the Prophets as the story is told in an expanding world, preached and taught through continuing journeys and conflicts across multiple geographical and cultural settings around the Mediterranean basin. (Acts plays a double role here, part Torah, part Prophets; Luke, by writing a two-volume work, nicely expands the four Gospels into a five-volume Torah at the same time that he introduces the prophetical/apostolic lives of Peter and Paul.) James and the Revelation are equivalent to the Writings, summing up in wisdom (James) and worship (Revelation) the response of a people whose lives are shaped by the story that they have heard and told in faith.

What must be insisted upon in exegesis is that the Scriptures come to us in this precise, canonical shape, a deeply comprehensive narrative framework gathering all the parts – proverbs, commandments, letters, visions, case law, songs, prayer, genealogies – into the story, a unified structure of narrative and imagery.

It is fatal to exegesis when this narrative sense is lost, or goes into eclipse. Every word of Scripture fits into its large narrative context in one way or another, so much so that the immediate context of a sentence is as likely to be eighty-five pages off in words written three hundred years later as to be the previous or the next paragraph. When the narrative sense is honored and nurtured, everything connects and meanings expand, not arbitrarily but organically – narratively. We see this at work in the narrative – soaked exegesis of a preacher like John Donne whose texts always lead us “like a guide with a candle, into the vast labyrinth of Scripture, which to Donne was an infinitely bigger structure than the cathedral he was preaching in.”

At the moment words are written down they immediately become what has been called “context free.” The tone of voice, the smell in the air, the wind on the check – these are gone. Yet, when we carefully observe the way language actually works in our practice of it, we know that this living context in which we speak and hear words is critically important. Setting, tone, inflection, gesture, weather – all of this matters. Most of this context is lost in the act of writing. But one thing is not lost: the basic narrative form itself, language shaped into story.

Since this is the one part of the context that we do have, we must not let any part of it slip from our attention: the Genesis to Revelation context, the basic story laid down in Torah and Gospels, the intrusion of story into history by means of Prophets and Epistles, the gathering response and anticipation of closure in Psalms and Revelation.

Most misunderstandings come not from missed definitions but from missed contexts. Why do we miss another’s meaning so frequently – in marriage, in international relations, in courtrooms? It is not because we do not understand the language; it is because we do not know the context. Professional listeners (counselors and therapists) spend hours listening to a person’s story before they even begin to understand. They get the message in the first twenty minutes – why then does it take so long? What are they listening for? In a word, context: all the contexts of family and work, school and sex, feelings and dreams that intersect in the human. A word used in one context reverses meaning in another. Understanding another person intimately takes years; a lifetime is not enough. The more context we are familiar with, the more understanding we develop.

Whether in reading Scripture or in conversing around the kitchen table, an isolated sentence can only be misunderstood. The more sentences we have, the deeper the sense of narrative is embedded in our minds and imaginations and the more understanding is available. Matthew is incomprehensible separated from Exodus and Isaiah. Romans is an enigma without Genesis and Deuteronomy. Revelation is a crossword puzzle without Ezekiel and the Psalms’.

– Eugene H. Peterson, Working the Angles: The Shape of Pastoral Integrity (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1987), 120–25.

‘Karitane, New Year’s Day’

An ancient fugue echoes

echoes from the beach near

the steep hill at Waikouaiti

across the bay towards

Karitane as another receding

tide near Old Head Street

exposes a feast of fresh

clams. Red-billed gulls and

caspian terns in saturnalia,

but still they squabble and

dash in bursts, their lowered

necks across drying sand.

An old man with

a bright blue t-shirt and

a bright yellow life-jacket, who

gently paddles an undersized

purple sea kayak. A

dog looks on. I guess

you could say that it’s

unimpressed. And a dozen

or so kids drop

baited lines from the pier

now also looking remarkably hopeful,

though less than was

true an hour ago.

And as the wind picks

up, a woman with calves

like boab trees waddles

past with a fluffy

dog far too energetic for

such a place, and the

water’s surface begins to

break. It is afternoon

after all – the time for

tide’s turning and a welcomed

coolness from the stinging

Otago sun. The auditory

and the gustatory notes creep

towards the repeat bar.

© Jason Goroncy

1 January 2012

Walter Brueggemann on the imagination and preaching

In his wonderful book, Rabbit is Rich, John Updike offers the following observation: ‘Laugh at ministers all you want, they have the words we need to hear, the ones the dead have spoken’. Here Updike is suggesting that religious language, the Bible’s language, or what he calls ‘the words … the dead have spoken’ are the very bread and butter of a minister’s vocabulary, words which determine not only the content of a minister’s speech but also the conduct associated with a minister’s speech. Indeed, ministers are permitted to speak only that which has been given. All other words are only waffle, a foul and unholy wind. No wonder that Bonhoeffer said that ‘teaching about Christ begins in silence’. For the words which the dead have spoken are, as Walter Brueggemann reminds us in his book on the psalms, ‘words that linger with power and authority after their speakers have gone’. Brueggemann understands the psalmists and prophets to be the great poets of our tradition, who speak to God out of the fullness of the human condition. He considers the entire psalter as a collection of three kinds of psalms: there are psalms of orientation, psalms of disorientation, and psalms of new orientation. ‘Poets exist so that the dead may vote’, said Elie Wiesel, and they vote in the Psalms. ‘They vote for faith’, says Brueggemann. ‘But in voting for faith they vote for candor, for pain, for passion – and finally for joy. Their persistent voting gives us a word that turns out to be the word of life’. Brueggemann is concerned about the kind of exclusively happy-clappy churchianity that exists, saying that ‘the problem with a hymnody that focuses on equilibrium, coherence, and symmetry (as in the psalms of orientation) is that it may deceive and cover over. Life is not like that. Life is so savagely marked by incoherence, a loss of balance, and unrelieved asymmetry’. True poets, painters, musicians etc. take the fullness of creaturely life seriously and, insofar as they do this, open up space in which the Holy Dove of God has room to flutter her wings.

In his wonderful book, Rabbit is Rich, John Updike offers the following observation: ‘Laugh at ministers all you want, they have the words we need to hear, the ones the dead have spoken’. Here Updike is suggesting that religious language, the Bible’s language, or what he calls ‘the words … the dead have spoken’ are the very bread and butter of a minister’s vocabulary, words which determine not only the content of a minister’s speech but also the conduct associated with a minister’s speech. Indeed, ministers are permitted to speak only that which has been given. All other words are only waffle, a foul and unholy wind. No wonder that Bonhoeffer said that ‘teaching about Christ begins in silence’. For the words which the dead have spoken are, as Walter Brueggemann reminds us in his book on the psalms, ‘words that linger with power and authority after their speakers have gone’. Brueggemann understands the psalmists and prophets to be the great poets of our tradition, who speak to God out of the fullness of the human condition. He considers the entire psalter as a collection of three kinds of psalms: there are psalms of orientation, psalms of disorientation, and psalms of new orientation. ‘Poets exist so that the dead may vote’, said Elie Wiesel, and they vote in the Psalms. ‘They vote for faith’, says Brueggemann. ‘But in voting for faith they vote for candor, for pain, for passion – and finally for joy. Their persistent voting gives us a word that turns out to be the word of life’. Brueggemann is concerned about the kind of exclusively happy-clappy churchianity that exists, saying that ‘the problem with a hymnody that focuses on equilibrium, coherence, and symmetry (as in the psalms of orientation) is that it may deceive and cover over. Life is not like that. Life is so savagely marked by incoherence, a loss of balance, and unrelieved asymmetry’. True poets, painters, musicians etc. take the fullness of creaturely life seriously and, insofar as they do this, open up space in which the Holy Dove of God has room to flutter her wings.

Revelation, healing, hope, forgiveness, worship, prayer, the transformation and redemption of human community – what are these if not fundamentally engaged with the matter of the human imagination. The psalmists new this. The prophets new this. And Brueggemann calls upon preachers today to embrace a like posture with the utmost seriousness. He begins his book The Prophetic Imagination with the following words:

The contemporary American church is so largely enculturated to the American ethos of consumerism that it has little power to believe or to act. This enculturation is in some way true across the spectrum of church life, both liberal and conservative. It may not be a new situation, but it is one that seems especially urgent and pressing at the present time. That enculturation is true not only of the institution of the church but also of us as persons. Our consciousness has been claimed by false fields of perception and idolatrous systems of language and rhetoric.

The internal cause of such enculturation is our loss of identity through the abandonment of the faith tradition. Our consumer culture is organized against history. There is a depreciation of memory and a ridicule of hope, which means everything must be held in the now, either an urgent now or an eternal now. Either way, a community rooted in energizing memories and summoned by radical hopes is a curiosity and a threat in such a culture. When we suffer from amnesia every form of serious authority for faith is in question, and we live unauthorized lives of faith and practice unauthorized ministries.

The church will not have power to act or believe until it recovers its tradition of faith and permits that tradition to be the primal way out of enculturation. This is not a cry for traditionalism but rather a judgment that the church has no business more pressing than the reappropriation of its memory in its full power and authenticity. And that is true among liberals who are too chic to remember and conservatives who have overlaid the faith memory with all kinds of hedges that smack of scientism and Enlightenment.

He continues:

… The task of prophetic ministry is to nurture, nourish, and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture around us … So, my programmatic urging is that every act of a minister who would be prophetic is part of a way of evoking, forming, and reforming an alternative community. And this applies to every facet and every practice of ministry. It is a measure of our enculturation that the various acts of ministry (for example, counseling, administration, even liturgy) have taken on lives and functions of their own rather than being seen as elements of the one prophetic ministry of formation and reformation of alternative community … [I]f the church is to be faithful it must be formed and ordered from the inside of its experience and confession and not by borrowing from sources external to its own life.

So in calling upon preachers to take seriously the role of the imagination, Brueggemann is not asking us to discard our own tradition and to take on something new. Rather, he is inviting us to do what God’s prophets and apostles have always done – to hear and to see and to taste and to touch and to speak the word of God, and to do so with all the powers of new imaginings that God has given to us, even in our own tradition, so that we might wrestle with the Word of God, with the old old story, as if for the first time, and have our lives formed by it.

In another book, Finally Comes the Poet, Brueggemann turns his attention specifically to preachers:

The gospel is too readily heard and taken for granted, as though it contained no unsettling news and no unwelcome threat. What began as news in the gospel is easily assumed, slotted, and conveniently dismissed. We depart having heard, but without noticing the urge to transformation that is not readily compatible with our comfortable believing that asks little and receives less.

The gospel is thus a truth widely held, but a truth greatly reduced. It is a truth that has been flattened, trivialized, and rendered inane. Partly, the gospel is simply an old habit among us, neither valued nor questioned. But more than that, our technical way of thinking reduces mystery to problem, transforms assurance into certitude, revises quality into quantity, and so takes the categories of biblical faith and represents them in manageable shapes.

He continues:

When truth is mediated in such positivistic, ideological, and therefore partisan ways, humaneness wavers, the prospect for humanness, is at risk, and unchecked brutality makes its appearance. We shall not be the community we hope to be if our primary communications are in modes of utilitarian technology and managed, conformed values. The issues facing the church and its preachers may be put this way: Is there another way to speak? Is there another voice to be voiced? Is there an alternative universe of discourse to be practiced that will struggle with the truth in ways unreduced? In the sermon – and in the life of the church, more generally, I propose – we are to practice another way of communication that makes another shaping of life possible; unembarrassed about another rationality, not anxious about accommodating the reason of this age.

The task and possibility of preaching is to open out the good news of the gospel with alternative modes of speech – speech that is dramatic, artistic, capable of inviting persons to join in another conversation, free of the reason of technique, unencumbered by ontologies that grow abstract, unembarrassed about concreteness. Such speech, when heard in freedom, assaults imagination and pushes out the presumed world in which most of us are trapped. Reduced speech leads to reduced lives. Sunday morning is the practice of a counter life through counter speech. The church on Sunday morning, or whenever it engages in its odd speech, may be the last place left in our society for imaginative speech that permits people to enter into new worlds of faith and to participate in joyous, obedient life.

To address the issue of a truth greatly reduced requires us to be poets that speak against a prose world. The terms of that phrase are readily misunderstood. By prose I refer to a world that is organized in settled formulae, so that even pastoral prayers and love letters sound like memos. By poetry, I do not mean rhyme, rhythm, or meter, but language that moves like Bob Gibson’s fast ball, that jumps at the right moment, that breaks open old worlds with surprise, abrasion, and pace. Poetic speech is the only proclamation worth doing in a situation of reductionism, the only proclamation, I submit, that is worthy of the name preaching. Such preaching is not moral instruction or problem solving or doctrinal clarification. It is not good advice, nor is it romantic caressing, nor is it a soothing good humor.

It is, rather, the ready, steady, surprising proposal that the real world in which God invites us to live is not the one made available by the rulers of this age. The preacher has an awesome opportunity to offer an evangelical world: an existence shaped by the news of the gospel. This offer requires special care for words, because the baptized community awaits speech in order to be a faithful people. What a way to think about a poetic occasion that moves powerfully to expose the prose reductions around us as false! … Because we live so close to the biblical text, we often fail to note its generative power to summon and evoke new life. Broadly construed, the language of the biblical text is prophetic: it anticipates and summons realities that live beyond the conventions of our day-to-day, take-for-granted world. The Bible is our firm guarantee that in a world of technological naivete and ideological reductionism, prophetic construals of another world are still possible, still worth doing, still longingly received by those who live at the edge of despair, resignation, and conformity. Our preferred language is to call such speech prophetic, but we might also term it poetic. Those whom the ancient Israelites called prophets, the equally ancient Greeks called poets. The poet/prophet is a voice that shatters settled reality and evokes new possibility in the listening assembly. Preaching continues that dangerous, indispensable habit of speech. The poetic speech of text and of sermon is a prophetic construal of a world beyond the one taken for granted … This poetic/prophetic utterance runs great risk. It runs the risk of being heard as fantasy and falsehood … The more tightly we hold to settled reality, the more likely the alternative construal of the poet will be dismissed as ‘mere fiction’. The poet/prophet, however, does not flinch from ‘fiction’, for the alternative envisioned in such speech is a proposal that destabilizes all our settled ‘facts’, and opens the way for transformation and the gift of newness.

And so Brueggemann encourages us to think of preaching as ‘a poetic construal of an alternative world’, the purpose of which is to ‘cherish the truth, to open the truth from its pervasive reductionism in our society, to break the fearful rationality that keeps the news from being new … After the engineers, inventors, and scientists, after all such through knowledge, “finally comes the poet”. The poet does not come to have a say until the human community has engaged in its best management. Then perchance comes the Power of poetry – shattering, evocative speech that breaks fixed conclusions and presses us always toward new, dangerous, imaginative possibilities … This speech, entrusted to and practiced by the church, is an act of relentless hope; an argument against the ideological closing of life we unwittingly embrace’.

It is precisely this posture towards and way of thinking about the poetic and fantastic (i.e., from fantasy, fiction, etc.) nature of reality and the shape of divine revelation that is just so imperative, not only for preaching but also for prayer, for pastoral encounters, for crafting liturgy, for choreographing church leadership structures and meetings, etc. Surely one of the main roles for leaders of faith communities is to help transform and foster our imaginations with the rich and fundamental traditions and texts that have formed us as a people, and to help God’s people to hear those afresh, as if for the first time. And for leaders of Christian faith communities, this means fostering an imagination baptised in the promises and stories of the Bible, seeing and hearing and tasting them as God’s ever-new speech.

And what art encourages is the opening up of hermeneutical space wherein our questions are taken seriously, where we can feel safer to explore them with God and with God’s people. Such a posture is something of a confession too; a confession that (i) there is truth that desires to be known; and (ii) we do not and cannot monopolise and control the truth of things.

Brueggemann reminds us that the meeting of the community of faith is an odd kind of speech meeting which ‘has the potential of evoking a new humanity’. And he suggests that in order for the new reality to be birthed, four partners need to be present:

1. The first partner in the meeting is the text. The congregation gathers with a vague memory of the text – a memory that has the text mostly reduced, trivialized, and domesticated.

2. The second partner in the meeting is the baptized. The community, he suggests in Finally Comes The Poet, ‘gathers to be shaped by a text that addresses us, an articulation of reality that lies outside of us that we cannot conjure and need not defend. The ones gather have been baptized. They may understand in an inchoate [i.e., tentative, embryonic, etc] way, but they have in fact made some vague decision about the cruciality of this text. They do not have a clear articulation of the text’s authority. Or they have a clear articulation that has become so scholastic as to be without use. Nonetheless, they are prepared to accept, in a general way, that this text is their text, the voice of life addressed to them’. He continues:

The baptized then, have been struggling with this text. The ones gathered are those who have either been other texts and have found them wanting, or have greatly resisted other texts and need this text reiterated Once again. Either way, out of compromise or resistance, the community gathers not for entertainment or private opinion, even for problem solving, but for the text made available yet again. They gather to hear the text that is shamelessly theological, candidly kerygmatic, and naively eschatological. The community waits for the text that may be a tent for the spirit. It waits with the hopeful yearning that the ‘house of authority’ is still intact. But if the text is to claim authority it will require neither the close reasoning of a canon lawyer, nor the precision of a technician, but it will require an artist to render the text in quite fresh ways, so that the text breaks life open among the baptized as it never has before.

3. Third, Brueggemann avers, there is ‘this specific occasion for speech’. Here he notes that ‘when the music stops and the rheostat is turned down, then there is this precious, awesome moment of speech’:

It is not time for cleverness or novelty. It is not time for advice or scolding or urging, because the text is not any problem-solving answer or a flat, ideological agent that can bring resolve. This moment of speech is a poetic rendering in a community that has come all too often to expect nothing but prose. It is a prose world for all those who must meet payrolls and grade papers and pump gas and fly planes. When the text, too, has been reduced to prose, life becomes so prosaic that there is a dread dullness that besets the human spirit. We become mindless conformists or angry protesters, and there is no health in us. We become so beaten by prose that only poetic articulation has a chance to let us live.

Into this situation, in this moment, the preacher must speak. She does not get to speak a new text. She must speak an old text – the one everybody knows. From the very first syllable, the ending is already known. But it is a script to be played afresh, so that in this moment of drama the players render the play as a surprise to permit a fresh hearing, a second opinion. It is an artistic in which the words are concrete but open, close our life but moving out to new angles of reality. At the end, there is a breathless waiting: stunned, not sure we have reached the end. Then there is a powerful sense that a world has been rendered in which I may live, a world that is truly home but from which I have been alienated. The speaker must truly be a poet. After the scientist and the engineer, ‘finally comes the poet’ (which Israel calls prophet) – to evoke a different world, a new song, a fresh move, a new identity, a resolve about ethics, a being at home.

4. Brueggemann’s fourth and final cadence concerns the fact that in the voice that takes the old script and renders it to evoke a world we had not yet witnessed (cf. Isa 43.19), a ‘better world [is] given as fresh revelation’. ‘Something’, he insists, ‘is revealed’, and ‘we know not how’. He continues:

A probe behind the closed parameters of religion too-long settled and politics too easily comfortable. It is not only truth disclosed, but it is life disclosed. Life unclosed, Life made open, certitudes broken so that we can redecide, images moving, imagination assaulting ideology. We find new configurations of life yet unformed, unthought, but now available. The old slogans sound unconvincing. I thought I had come for certitude, but the poetic speech does not give certitude. As I am addressed by the gospel, I hear anew that possibility overwhelms necessity in my life. The only available absolute given me is a ‘fiction’ to which I must trust myself – a gracious ‘fiction’ on which I stake my life, authored by God who also authors the text and the speech.

The congregation departs. Same old quarrels in the car on the way home. Same old tensions at dinner. Same tired beginning on Monday. Now, however, there is disclosed a new word, a new hope, a new verb, a new conversation, a new risk, a new possibility. It is not a new truth, but rather one long known that had been greatly reduced. That long-known truth is now greatly enhanced in riches, texture, availability, demand. My life is mapped in mystery and I accept that new life; but it is also mapped in vulnerability and it frightens me. The mystery gives regal authority and freedom in the face of an IRS audit. The vulnerability permits me to come out from behind my desk, my stethoscope, my uniform, my competence, my credentials, my fears – to meet life a little more boldly. Yet again, as the word is spoken one more time, we move through the wearisome death-ridden days of our life and come back once again to Easter to be stunned into disbelief, and then beyond disbelief, to be stunned to life, now filled with fear and trembling.

The meeting involves this old text, the spent congregation believing but impoverished, the artist of new possibility, the disclosure. The Prince of Darkness tries frantically to keep the world closed so that we can be administered. The Prince has such powerful allies in this age. Against such enormous odds, however, there is the working of this feeble, inscrutable, unshackled moment of sermon. Sometimes the Prince will win the day and there is no new thing uttered or heard. Sometimes, however, the sermon will have its say and the truth looms large – larger than the text or the voice or the folk had any reason to expect. When that happens, the world is set loose toward healing. The sermon for such a time shames the Prince and we become yet again more nearly human. The Author of the text laughs in delight, the way that Author has laughed only at creation and at Easter, but laughs again when the sermon carries the day against the prose of the Dark Prince who wants no new poetry in the region he thinks he governs. Where the poetry is sounded, the Prince knows a little of the territory has been lost to its true Ruler. The newly claimed territory becomes a new home of freedom, justice, peace, and abiding joy. This happens when the poet comes, when the poet speaks, when the preacher comes as poet.

‘Uneasy Rider? The Challenge to a Ministry of Word and Sacrament in a Post-Christendom Missional Climate’

The Inaugural Lecture for the 2012 academic year for students at the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership was delivered by my colleague the Rev Mark Johnston. A copy of the lecture – ‘Uneasy Rider? The Challenge to a Ministry of Word and Sacrament in a Post-Christendom Missional Climate’ – is now available for download (pdf,ppt). Previous inaugural lectures can be downloaded by visiting here.

The Inaugural Lecture for the 2012 academic year for students at the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership was delivered by my colleague the Rev Mark Johnston. A copy of the lecture – ‘Uneasy Rider? The Challenge to a Ministry of Word and Sacrament in a Post-Christendom Missional Climate’ – is now available for download (pdf,ppt). Previous inaugural lectures can be downloaded by visiting here.

Midweek recharge

Theatrical Theology: Conversations on Performing the Faith

The Institute for Theology, Imagination, and the Arts (University of St Andrews) is hosting a conference on the theme Theatrical Theology: Conversations on Performing the Faith, held in St Andrews on 15-17 August 2012. Here’s the blurb:

The Institute for Theology, Imagination, and the Arts (University of St Andrews) is hosting a conference on the theme Theatrical Theology: Conversations on Performing the Faith, held in St Andrews on 15-17 August 2012. Here’s the blurb:

Influenced and inspired by Hans Urs von Balthasar’s seminal work in The Theo-Drama, a growing number of contemporary scholars in various theological disciplines are discovering the potential for interdisciplinary conversation between theology and theatre. From a theological perspective, there are several reasons why drama and theatre present themselves as particularly fitting conversation partners, including the inherently dramatic form of God’s revelation in word and deed, the role of Scripture as a text which invites performance rather than passivity, faithful action as both the goal and means of theological understanding, the public and communal nature of theology, and the indeterminacy, provisionality, and ‘improvised’ nature of the theological task. For its part, theatre has always been compelled to acknowledge a debt to its ancient and longstanding entanglements with religious and theological perspectives, and may have much to gain from the process of revisiting and responding to these, not least in their present-day Christian form.

The task of pursuing a serious and constructive interdisciplinary exchange between theatre and theology, however, is one that has only just begun. Furthermore, suspicions persist in some theological quarters regarding the value of interdisciplinary approaches to theology as such, and towards theatre in particular which, among the arts, has experienced a particularly volatile relationship with the Church across the centuries. In response to all of this, Theatrical Theology: Conversations on Performing the Faith will seek to demonstrate the fruitfulness for constructive Christian theology and theatre alike of pursuing the conversation further, tracing some of the advances that have already been made, and identifying new challenges and opportunities still to be reckoned with as the interaction continues and develops further.

Our plenary speakers are among those whose work has already embarked upon the conversation between theology and theatre, including Shannon Craigo-Snell (Louisville Seminary), David Cunningham (Hope College), Jim Fodor (Bonaventure) Timothy Gorringe (Exeter), and Ivan Khovacs (Canterbury Christ Church). In addition to these plenary presentations, there will be several short paper sessions on the conference theme. Furthermore, it is expected that the conference programme will include conversations with theatre practitioners and a specially staged theatrical performance.

Short papers proposals are invited on the conference theme, including the following topics:

- Theatrical models and metaphors in Christian theology

- Character formation for life and the stage

- Ethics, improvisation, and performative wisdom

- Christian practices and theatrical skills

- Scripture as dramatic text

- Liturgy, worship, and performance

- Theodramatic ecclesiology and company life

- Mission and audience participation

- Stage, place and contextual theology

- Embodiment and performing the faith

Proposals should be for 20-minute papers to be followed by 10 minutes for questions. Please include in the proposal your name, institution, paper title, and abstract (not exceeding 200 words). Paper proposals will be considered immediately, and please send submissions by email to Theatrical.Theology@st-andrews.ac.uk before the deadline 15 June, 2012. More information regarding conference proceedings and registration will be available soon at www.theatricaltheology.co.uk.

On hate

hate suits him

better than forgiveness.

Immersed in hate

he doesn’t have

to do anything;

he can be

paralyzed, and the

rigidity of hatred

makes a kind

of shelter for

him.

– John Updike, Rabbit, Run

Jason A. Goroncy: a draft obituary

Offered in the spirit of the ars moriendi:

Offered in the spirit of the ars moriendi:

‘Under this rock lies a man who, in all earnestness and with every endeavour, tried and failed (although not every time) to, sometimes humorously and sometimes less so, enlighten the world around him (by world, I mean his colleagues at the Knox Centre, at Knox College and the wider world through his blogging and use of social networks, although not Facebook, which he despised for reasons expressed loudly and often, but which were largely invalid) about the merits of PT Forsyth and Karl Barth and to provide them with a map which, if followed carefully, would assist them to more accurately understand Forsyth’s and Barth’s contribution within a wider landscape of theological conversation and be persuaded of the importance of Christology above all – disappointingly, he mastered neither spelling nor grammar nor the assiduous use of a full stop’. – Catherine van Dorp

‘At My Father’s Funeral’, by John Burnside

The idea that the body as well as the soul was immortal was probably linked on to a very primitive belief regarding the dead, and one shared by many peoples, that they lived on in the grave. This conception was never forgotten, even in regions where the theory of a distant land of the dead was evolved, or where the body was consumed by fire before burial. It appears from such practices as binding the dead with cords, or laying heavy stones or a mound of earth on the grave, probably to prevent their egress, or feeding the dead with sacrificial food at the grave, or from the belief that the dead come forth not as spirits, but in the body from the grave. – J.A. MacCulloch, The Religion of the Ancient Celts.

We wanted to seal his mouth

with a handful of clay,

to cover his eyes

with the ash of the last

bonfire he made

at the rainiest edge

of the garden

and didn’t we think, for a moment,

of crushing his feet

so he couldn’t return to the house

at Halloween,

to stand at the window,

smoking and peering in,

the look on his face

like that flaw in the sway of the world

where mastery fails

and a hinge in the mind

swings open – grief

or terror coming loose

and drifting, like a leaf,

into the flames.

[Source: London Review of Books 34 No. 2 (26 January 2012), 18]

Kafka on writing

‘Writing means revealing onesself to excess … This is why one can never be alone enough when one writes, why even night is not night enough … I have often thought that the best mode of life for me would be to sit in the innermost room of a spacious locked cellar with my writing things and a lamp. Food would be brought and always put down far away from my room, outside the cellar’s outermost door. The walk to my food, in my dressing gown, through the vaulted cellars, would be my only exercise. I would then return to my table, eat slowly and with deliberation, then start writing again at once. And how I would write! From what depths I would drag it up! without effort!’

‘Writing means revealing onesself to excess … This is why one can never be alone enough when one writes, why even night is not night enough … I have often thought that the best mode of life for me would be to sit in the innermost room of a spacious locked cellar with my writing things and a lamp. Food would be brought and always put down far away from my room, outside the cellar’s outermost door. The walk to my food, in my dressing gown, through the vaulted cellars, would be my only exercise. I would then return to my table, eat slowly and with deliberation, then start writing again at once. And how I would write! From what depths I would drag it up! without effort!’

– Franz Kafka, ‘Letter, 14–15 January 1913’, in Letters to Felice (trans. James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth; Minerva: Mandarin Paperbacks, 1992), 184.

January stations …

- The Reformation by Diarmaid MacCulloch (a re-read, but fruitful every time).

- The Reformation Theologians: An Introduction to Theology in the Early Modern Period by Carter Lindberg.

- Calvin by Bruce Gordon (another re-read).

- Katharina Schütz Zell, Church Mother: The Writings of a Protestant Reformer in Sixteenth-Century Germany edited by Elsie McKee.

- Engaging With Calvin edited by Mark D. Thompson.

- Children of God: The Imago Dei in John Calvin and His Context by Jason Van Vliet.

- Cambridge Theology in the Nineteenth Century by David M. Thompson.

- Morning Knowledge by Kevin Hart.

- Sex, Marriage, and Family Life in John Calvin’s Geneva: Courtship, Engagement, and Marriage by John Witte Jr. and Robert M. Kingdon.

- Calvin by George W. Stroup.

- Letters to Felice by Franz Kafka.

- Calvin Today: Reformed Theology and the Future of the Church edited by Welker Michael, Michael Weinrich and Ulrich Möller.

- Calvin and the Duchess by F. Whitfield Barton.

- ChurchMorph: How Megatrends Are Reshaping Christian Communities by Eddie Gibbs.

Listening:

- Litany and Alina by Arvo Pärt.

- Bon Iver by Bon Iver.

- All Eternals Deck by Mountain Goats.

- Hymns of the 49th Parallel by K.D. Lang.

- Far Country by Andrew Peterson.

- Perotin, Gesualdo: Tenebrae and Palestrina: Canticum canticorum: Spiritual Madrigals by The Hilliard Ensemble.

- Musik der Reformation: Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott.

- Luke: A World Turned Upside Down by Michael Card.

- El Corazon, Washington Square Serenade, Townes, The Revolution Starts Now, Jerusalem and I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive by Steve Earle.

- Leave Your Sleep by Natalie Merchant.

- One To The Heart, One To The Head by Gretchen Peters with Tom Russell.

- Circus Girl, The Secret of Life, Gretchen Peters and Halcyon by Gretchen Peters.

- Old Ideas by Leonard Cohen.

Watching:

Michael Card and Peter Leithart: the polynymous man?

What’s Wrong with the World: An Inkling of a Response

Last Saturday, St. George Cathedral in Wichita hosted the second annual Eighth Day Symposium on ‘What’s Wrong with the World: An Inkling of a Response’. Here are the talks:

Last Saturday, St. George Cathedral in Wichita hosted the second annual Eighth Day Symposium on ‘What’s Wrong with the World: An Inkling of a Response’. Here are the talks:

1. Ralph Wood, What’s Wrong with the World: C.S. Lewis Offers an Inkling of a Response

2. Warren Farha, The Inklings: Friendship as a Source of Cultural Renewal

3. Stan Cox, Charles Williams: The Affirmation of Being as a Foundation of Christian Culture

4. Ralph Wood, What’s Right with the Church: G.K. Chesterton on the Sacramental Imagination

[HT: Ancient Faith Radio]

Welcome Ambrie Jordyn Goroncy

Apparently, lots of interesting things happened on 27 January: in 447, the Walls of Constantinople were severely damaged by an earthquake; in 1142, Yue Fei was executed; in 1186, Henry VI got hitched to Constance of Sicily; in 1343, Pope Clement VI issued some Bull called Unigenitus; in 1936, the BBC began its first public broadcasts; in 1974, the Brisbane River breached its banks in what was the largest flood to affect the city; in 1980, Robert Mugabe returned to Rhodesia; in 1984, Michael Jackson’s head caught fire during the filming of a Pepsi commercial; in 2010, Barack Obama made his first State of the Union address and Steve Jobs unveiled the iPad tablet. It’s also the date upon which the following people died – Rita Angus, Mahalia Jackson, John Updike, J.D. Salinger, and Howard Zinn.

Apparently, lots of interesting things happened on 27 January: in 447, the Walls of Constantinople were severely damaged by an earthquake; in 1142, Yue Fei was executed; in 1186, Henry VI got hitched to Constance of Sicily; in 1343, Pope Clement VI issued some Bull called Unigenitus; in 1936, the BBC began its first public broadcasts; in 1974, the Brisbane River breached its banks in what was the largest flood to affect the city; in 1980, Robert Mugabe returned to Rhodesia; in 1984, Michael Jackson’s head caught fire during the filming of a Pepsi commercial; in 2010, Barack Obama made his first State of the Union address and Steve Jobs unveiled the iPad tablet. It’s also the date upon which the following people died – Rita Angus, Mahalia Jackson, John Updike, J.D. Salinger, and Howard Zinn.

Some cool stuff happened too: The trial of Guy Fawkes began; the National Geographic Society was founded; the Red Army liberated the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp; the Paris Peace Accords officially ended the Vietnam War; and Lewis Carroll, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling and David Strauss celebrated their birthdays.

But by far the most interesting and cool thing was the birth of Ambrie Jordyn Goroncy. Her birth last Friday (when God ceased knitting and became a midwife), during respectable hours, was anticipated in this poem, and follows fairly swiftly on the heels of that of her awesome brother Samuel Jamieson, and some five years after that of her theologian-sister Sinéad Chloe (regulars here to PCaL will be familiar with Sinéad’s developing and prayerful theology). All occupants at our house are tired and well, including the sheep, one of whom recently gave birth too. So far, Ambrie seems perfect. That will change when she becomes a Christian at her baptism on 4 March.

Donald MacKinnon on the very stuff of human existence

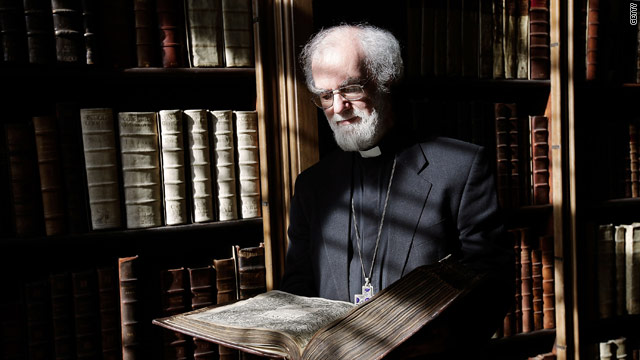

In the midst of some fruitful discussion generated by the recent posts on Rowan Williams by Chris Green and Joel Daniels, a friend of mine (who also happens to be an outstanding MacKinnon scholar) shared these words with me. I’ve been meditating on them all week, and thought that they were worth sharing here not only for what they tell us about MacKinnon’s mind (and perhaps too about Williams’), but also for what they tell us about ourselves and about our being overcome, and – here playing the risk of presumptuousness – of the depths that such overcoming involves:

In the midst of some fruitful discussion generated by the recent posts on Rowan Williams by Chris Green and Joel Daniels, a friend of mine (who also happens to be an outstanding MacKinnon scholar) shared these words with me. I’ve been meditating on them all week, and thought that they were worth sharing here not only for what they tell us about MacKinnon’s mind (and perhaps too about Williams’), but also for what they tell us about ourselves and about our being overcome, and – here playing the risk of presumptuousness – of the depths that such overcoming involves:

At its heart there lies the recognition that historical self-consciousness belongs to the very stuff of human existence, that freedom in the sense of a true autonomy is at once the foundation of our every effort to make sense of our inheritance; but that it is a freedom menaced all the time by forces, many but not all of which lie outside our control, facing us by the pressure of their ugly insistence upon our purposings with a sense of overmastering futility, defeat, even besetting cruelty. The threat is of something much more profound than that of Cartesian malin génie, it is the menace of a backlash somehow built into the heart of things that will lay our sanity itself in ruins. We are face to face not with a grisly theodicy that allows historical greatness to provide its own moral order (there are more than hints of this in Hegel) but with a cussedness which seems totally recalcitrant to the logos of any justification of the ways of God to man. And here the last word is with the cry of redemption.

– Donald M. MacKinnon, ‘Finality in Metaphysics, Ethics and Theology’ in Explorations in Theology, Volume 5 (London: SCM Press, 1979), 105–06.

Being has a memory

‘Toward the end of To the Castle and Back, [Václav Havel’s] unconventional presidential memoir, in a section datelined “Hrádeček, December 5, 2005,” Havel confronts the question of his own death. “I’m running away,” he writes.

‘Toward the end of To the Castle and Back, [Václav Havel’s] unconventional presidential memoir, in a section datelined “Hrádeček, December 5, 2005,” Havel confronts the question of his own death. “I’m running away,” he writes.

What I’m running away from is writing. But it’s more than that. I’m running away from the public, from politics, from people. Perhaps I’m even running away from the woman who saved my life. Above all, I’m probably running away from myself.

He finds himself constantly fretting about the tidiness of the house, as though he were expecting a visit from someone “who will really appreciate that everything is in its proper place and properly aligned.” Why this obsession with order?

“I have only one explanation,” he says.

I am constantly preparing for the last judgment, for the highest court from which nothing can be hidden, which will appreciate everything that should be appreciated, and which will, of course, notice anything that is not in its place. I’m obviously assuming that the supreme judge is a stickler like me. But why does this final evaluation matter so much to me? After all, at that point, I shouldn’t care. But I do care, because I’m convinced that my existence—like everything that has ever happened—has ruffled the surface of Being, and that after my little ripple, however marginal, insignificant and ephemeral it may have been, Being is and always will be different from what it was before.

“All my life,” he went on,

I have simply believed that what is once done can never be undone and that, in fact, everything remains forever. In short, Being has a memory. And thus, even my insignificance—as a bourgeois child, a laboratory assistant, a soldier, a stagehand, a playwright, a dissident, a prisoner, a president, a pensioner, a public phenomenon, and a hermit, an alleged hero but secretly a bundle of nerves—will remain here forever, or rather not here, but somewhere. But not, however, elsewhere. Somewhere here’.

[Source: The New York Review of Books]

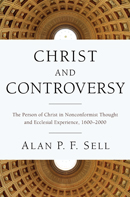

Christ and Controversy

The good folk over at Wipf and Stock have informed me that they have just released Alan Sell’s fascinating book Christ and Controversy: The Person of Christ in Nonconformist Thought and Ecclesial Experience, 1600–2000. Professor Sell’s name is no stranger here at PCaL. I was invited to pen a wee endorsement for the back cover (it’s SO much less work to get your name on the back cover of a book than it is to have is appear on the front). Here’s what I wrote:

The good folk over at Wipf and Stock have informed me that they have just released Alan Sell’s fascinating book Christ and Controversy: The Person of Christ in Nonconformist Thought and Ecclesial Experience, 1600–2000. Professor Sell’s name is no stranger here at PCaL. I was invited to pen a wee endorsement for the back cover (it’s SO much less work to get your name on the back cover of a book than it is to have is appear on the front). Here’s what I wrote:

This encyclopedic but accessible survey stands as witness to the church’s ongoing wrestle with an ancient question—’Who do you say that I am?’ It demonstrates Professor Sell’s acumen as a meticulous researcher, his contagious devotion to the nonconformist tradition, and his aptitude for bringing the dead back to life. With wit and sober-headedness, this bold and theologically-informed study records many christological enthusiasms and ecclesiological consequences that this perduring question has birthed—its invitation lingers still.

And the book’s description reads:

What may happen when Christians take doctrine seriously? One possible answer is that the shape of churchly life “on the ground” can be significantly altered. This pioneering study is both an account of the doctrine of the person of Christ as it has been expounded by the theologians of historic English and Welsh Nonconformity, and an attempt to show that while many Nonconformists held classical orthodox views of the doctrine between 1600 and 2000, others advocated alternative understandings of Christ’s person; hence the evolution of the ecclesial landscape as we have come to know it. The traditions here under review are those of Old Dissent: the Congregationalists, Baptists, Presbyterians and their Unitarian heirs; and the Calvinistic and Arminian Methodist bodies that owe their origin to the Evangelical Revival of the eighteenth century.

On Rowan Williams’ Theology

A guest post by Joel Daniels.

1) Williams exaggerates the importance of maintaining unsettledness, preventing resting, etc.

Williams shares with Donald MacKinnon a sense of the moral priority of tragedy, and one gets the sense that he sees a straight line from closure to murder. At the risk of being too flip about it, the road to genocide is paved with good intentions. Efficient systems, set up by well-meaning people, to accomplish the greatest ends, eventually justify the most atrocious horror: it is fitting that one man should die for the people. Or the shaken revolutionary Shigalyov in Dostoevsky’s Demons, who has written out the plan for the revolution, reporting that, “Starting from unlimited freedom, I conclude with unlimited despotism. I will add, however, that apart from my solution to the social formula, there is no other.” Efficient theoretical systems (economic, political, philosophical, theological) produce victims, with the crucified Christ, one without sin, being the pure example of this fact – though the history of the last century provides ample examples by itself. I think that this really is the overarching concern of Williams’ theology.

Part of this may simply be disposition: there’s a really revealing line in WWA where he’s comparing Balthasar and Rahner, and he writes, “for Balthasar, dialogue with ‘the world’ is so much more complex a matter than it sometimes seems to be for Rahner; because [for Balthasar] the world is not a world of well-meaning agnostics but of totalitarian nightmares, of nuclear arsenals, labor camps and torture chambers” (100). If you look at the world and see harmony, you end up in one theological place; if you see torture chambers, you end up in another. I think the relentless self-criticism comes from having the second perspective as his default.

The downside of this is what Chris described; Mike Higton (in Difficult Gospel) puts it this way: “But I suspect that the tenor or atmosphere of his [Williams’] writing is too unrelentingly agonized…” Perhaps so; I remember reading that MacKinnon couldn’t order lunch without severe moral anguish.

2) For Williams, the logical outcome of good theology is the silence of frustration, not of adoration.

What prevents simple frustration supplanting the possibility of positive worship is the strong element of Anglican orthopraxis at work: while it may be the case that the Cross reveals that there is nothing we can securely know or think (frustration), the practice of worship (adoration) takes priority over the practice of theology. It would be interesting to know whether Williams would adopt Pseudo-Dionysius’ use of “hymn” as a theological category, along the lines of the “celebratory” mode of theological work he describes. If so, perhaps we could say that good theology culminates not in silence, but in the singing of the liturgy. It’s as if the Eucharistic service provides a kind of foundation from which we can work and to which we can return: our Eucharistic celebration may not be perfect; it is certainly interpreted by fallible human beings; and entails its own risks (clericalism, among many others). Nonetheless, we can identify the effect of the Eucharist over the course of history to complicate any easy answers, by returning us to the broken body of Christ.

3) Similarly, the effect Williams has is to make it too difficult to talk about God; the end result is paralysis or restlessness.

It’s not so much that we shouldn’t make attempts to talk about God (paralysis), as that we have to realize that no attempt is ever final: it’s dialectic all the way down. Is this eternal restlessness? In a sense, I think it probably is. But I hope that it’s the restlessness of two lovers’ delight in each other, not the restlessness of dissatisfaction; the kind of restlessness that is the way that the meaning of a great text (for example) is never exhausted, but always there to be plumbed for meaning, new circumstances bringing out existing aspects of the same work in a different light.Further, some attempts at talking about God are better than others, and one of the benefits of the tradition is a head start, so to speak, in identifying which ones are going to be liberating and fecund, and which will lead to dead ends, inconsistencies with the Eucharist, or something worse.

4) Williams makes anti-programmatic thinking programmatic.

I can understand a concern about a conception of theology that sees as its primary objective the destabilization of every affirmative statement about God – especially when that destabilization is being done by a professional class that isn’t explicitly or especially in relationship with a worshipping community. There is a difference between a smirking hermeneutic of suspicion and a pious refusal of idolatry, but they may look quite similar on the page. Further, an affinity for disruption can become its own security blanket.

At the very least, we can see that Williams is aware of that: I frequently return to the sermon “The Dark Night,” with its first paragraph “If I am a ‘conservative’ my circular path will be one of conventional sacramental observance… If I am a ‘radical’ my God will be the disturber of the social order… Both of these pictures as they stand are delusional.” Both of them use God to accomplish some other ends. I think he does a pretty good job at this, keeping his own perspective under interrogation also.