In this insightful and encouraging interview, conducted with Terence Handley MacMath and first published in the Church Times, Rowan Williams ruminates on teaching, church leadership, theological education, funding, experiencing God, faith, the theological task, reporting on charities, his greatest influences, and reassuring and loved sounds. His comments – particularly those about the relationship between Christ and the world – are all the more pertinent given recently-published pieces in the mainstream media about what most of us, I suspect, have known for so long now, about Britain’s ‘disappearing Christianity’ and ‘Christian extinction’.

In this insightful and encouraging interview, conducted with Terence Handley MacMath and first published in the Church Times, Rowan Williams ruminates on teaching, church leadership, theological education, funding, experiencing God, faith, the theological task, reporting on charities, his greatest influences, and reassuring and loved sounds. His comments – particularly those about the relationship between Christ and the world – are all the more pertinent given recently-published pieces in the mainstream media about what most of us, I suspect, have known for so long now, about Britain’s ‘disappearing Christianity’ and ‘Christian extinction’.

My work is teaching, writing, studying, plus lots of administration and raising funds for the college, and chairing Christian Aid. Probably most of my time goes on college, and a variety of teaching events for churches and schools.

I’m currently giving a series of lectures here on the history of the doctrine of Christ, trying to tease out how thinking about Christ clarifies the relation between God and creation overall.

As Archbishop, you’re constantly responding to things, and even if you do get some writing done — as I did, a bit — it tends to be issue-focused. I like having the chance of some longer breaths for thinking through questions.

When I was in post, the urgent questions were often serious theological ones, if rather heavily disguised at times; so I found myself reflecting hard about the nature of authority in the Church, and what it meant to speak about the interdependent life of the Body of Christ. That latter point continues to be absorbing for me, and I think that this term’s lectures will have reflected that a bit — thinking about the inseparable connection between what we say about Jesus Christ, and what we say about the community that lives in him.

A bishop has to be a teacher of the faith. That is, he or she has to be someone who is animated by theology and eager to share it — animated by theology in the sense of longing to inhabit the language and world of faith with greater and greater intelligence, insight, and joy. So, yes, bishops need that animation and desire to help others make sense of their commitment.

Arguments about priestly training go round and round, don’t they? Too theoretical, too pragmatic, not enough of this, not enough of that. . . My worry is, if we focus too much on curriculum — what should the modules be? — we may somehow fail to connect things up in a big picture in which pastoral care, sacramental life, prayer, scripture, social and political perspective, and doctrine all interweave. We need to have that interconnectedness in our minds constantly, as we seek to shape future ordained ministry, because that is what provides the deepest resource for arid and frustrating times. And that is what guarantees that we have something to offer our society that’s more than simply religious uplift, moral inspiration, or nice experiences.

A lot of debate in and out of the Church is shadow-boxing, because people don’t recognise what the questions are. Of course, recognising what the questions are does not remotely guarantee that you will agree, but it helps to know what you’re disagreeing about, and stops you resorting to tribal slogans, whether secular or religious. My old friend and colleague Oliver O’Donovan is particularly good at this excavation of basic questions, and has been a great help and inspiration.

In an ideal world, government and educational establishments would recognise that theology is as significant a study as other humanities. But, given that the study of the humanities in general is so badly supported these days, I’m not holding my breath. It’s anything but an ideal world.

This means that I would plead with the Church to take seriously the need for investing in theological education at all levels — to recognise that there is a huge appetite for theology among so many laypeople, and thus a need for clergy who can respond and engage intelligently. The middle-term future may need to be one where there are more independent centres of theological study outside universities, given the erosion of resources in higher education, and I think it’s time more people started thinking about what that might entail in terms of funding.

British theology is more cosmopolitan than when I started studying it. In the Sixties, people writing about doctrine in the UK were not very enthusiastic about Continental writers (though it was different for New Testament scholars); and modern Roman Catholic theology was largely ignored. Now we read far more widely, I think, and we’re more ready to take time over the intricacies of historical arguments rather than dismiss them as tiresome and unnecessary complications.

There’s more critical interest in the history of spirituality, and more willingness to let it come into the territory of doctrine. All this is to the good. My sadness is the decline of institutional resources for theology in the UK: limited funds for research, and theology departments under threat.

It’s hard to pin down my first experience of God, but I suppose [it was] through shared worship in the Presbyterian chapel of my childhood, and a strong sense — when I was around eight, and my grandmother, who lived with us, was dying — of God’s care and providence, and the presence of the crucified Christ. Shared worship is still a major part of how I encounter God, but, from my teens, this has been balanced by a growing hunger for silence before God.

I’ve never felt any real disjunction between academic theology and faith. I’ve found that studying the development of Christian doctrine has excited me, and helped me see something of the veins and sinews of faith. My research has arisen out of my desire to understand better what we say as people of faith.

Apart from the obvious question about how we Anglicans manage the tension of living in a diverse global church — where we need a more robust theology of what interdependence does and doesn’t mean — I think my biggest concern is that we don’t have a rich enough Anglican theological consensus on the sacramental nature of the Church. That’s eucharistic ecclesiology, to put it in technical language.

Underrated theologians? John Bowker, Olivier Clément, Andrew Shanks.

Theology has a modest but vital part to play in the Church’s mission. We need to keep asking questions about how we’re using our language, so that we don’t get stuck with unexamined habits of speech, don’t assume that true formulations about God tell us everything about him, don’t forget the sheer scale of what we are daring to speak about. Theology helps with all this. And it helps clarify what we believe about human nature and destiny, which is of real importance for a world that is often deeply unsure or confused about the roots of human dignity.

Theologians don’t necessarily ask the same questions as others do, but there is a continuity, and theologians need the skill and patience to draw out those continuities. That’s why it is important that there are writers who try to work in the boundaries between academic theology and secular culture, and those who try to put the great governing themes of classical theology into plainer words. Mike Lloyd is a good example.

I was an only child. My father worked as an engineer, and my mother had lifelong health and mobility problems. They were both Christians, though reticent and sometimes uncertain about it. My wife, Jane, of course, is well-known in her own right as a teacher and writer. We have a daughter who teaches in an inner-city primary school, and a son studying drama at university. Both would still call themselves Christian, though they slip in and out of the institutional life of the Church.

The most reassuring, loved sound to me is the door opening when my wife or children come home.

Some irresponsible and hostile reporting about charities was the last thing that made me angry. Nationally and internationally, charities are expected to pick up the slack where statutory provision drops away — yet they’re subjected not just to proper demands for accountability, but often to what looks like wilfully negative and undermining reporting, focused on excessive salaries, inadequate monitoring of expenditure, intrusive fund-raising, and so on. These things all happen, and need to stop happening; but just how representative are the hostile headline stories, especially where international aid is concerned?

I’m happiest when I’m at the Pembrokeshire coast on family holidays.

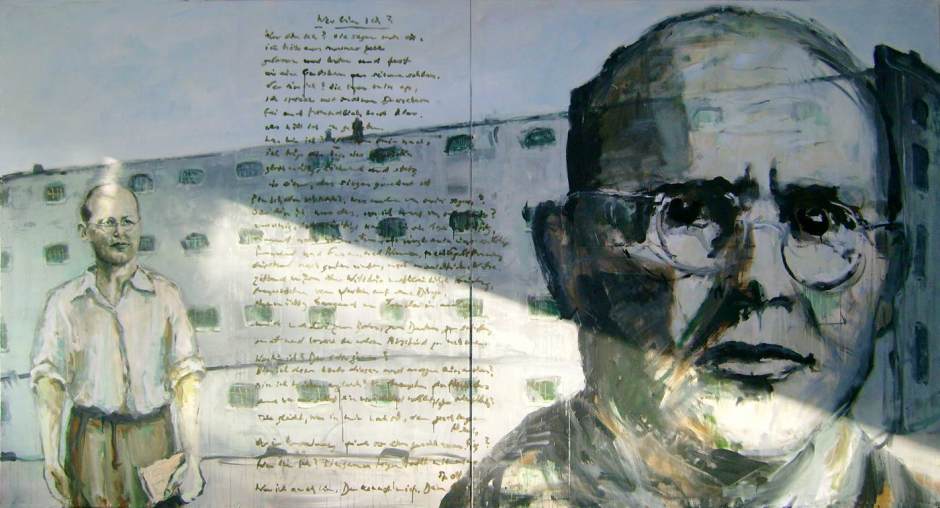

Augustine has probably been the greatest theological influence above all, but also Vladimir Lossky, who was the focus of my doctoral research; Barth, Bonhoeffer, Austin Farrer, Donald MacKinnon, James Alison. I don’t know if Simone Weil is allowed to count as a theologian; I don’t always agree with her by any means, but she was a huge influence at several points. Among specific books, I remember Bonhoeffer’s prison letters; Charles Williams’s He Came Down From Heaven; Herbert McCabe, Law, Love and Language; Hans Urs von Balthasar, Elucidations.

The greatest influences in my life have been the parish priest in my teenage years; the Benedictine monk who was my spiritual director; and Jane and the children.

I pray most for patience, freedom to forgive and let go of hurt — for myself and for the whole Church and human family — and for the rescue of the vulnerable: the abused, hungry, terrified, wherever they are.

If I had to choose a companion to be locked in a church with for a few hours, I’d toss up between St Augustine, T. S. Eliot, and Bonhoeffer, from the past. In the present — family apart — Salley Vickers, Michael Symmons Roberts, or Kathleen Norris.

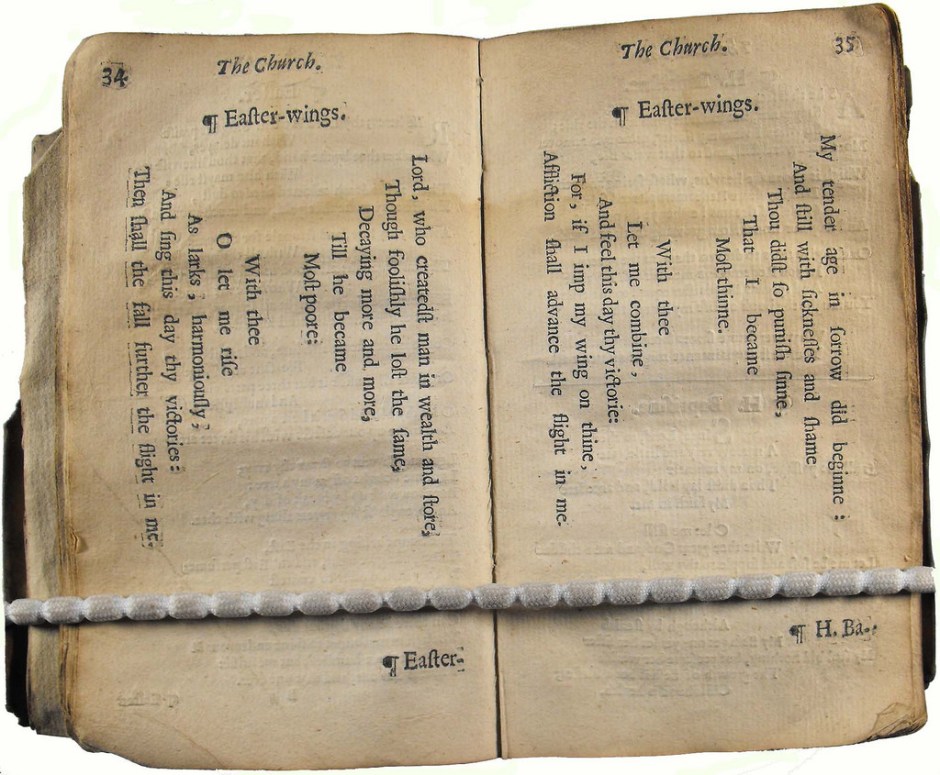

1535

1535

In this insightful and encouraging interview, conducted with Terence Handley MacMath and

In this insightful and encouraging interview, conducted with Terence Handley MacMath and

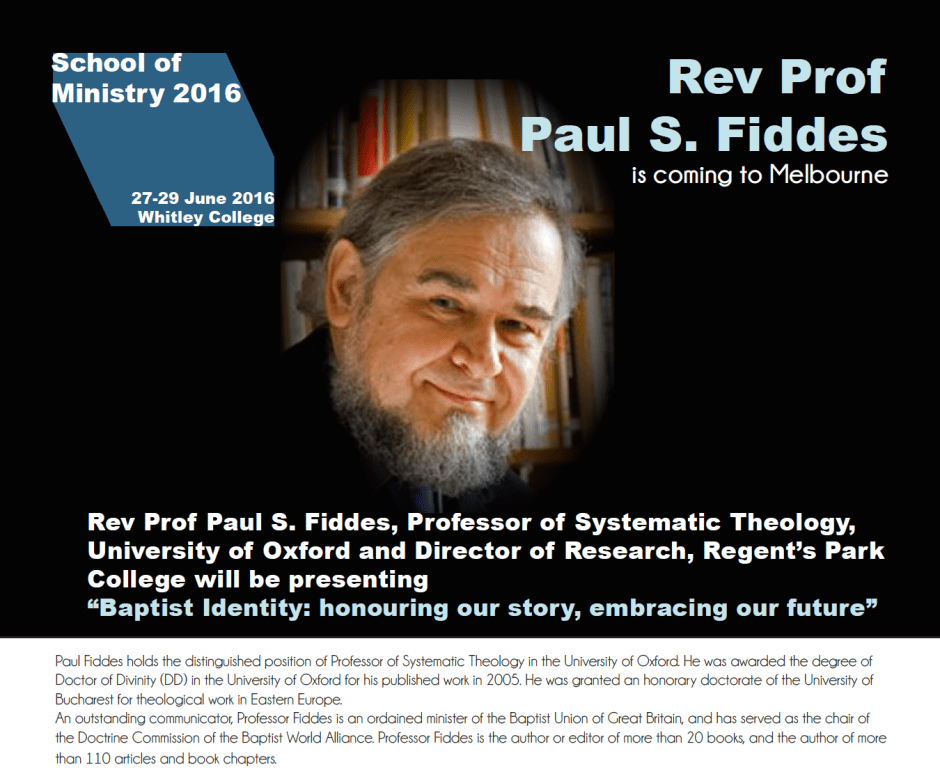

Malcolm Guite has

Malcolm Guite has  I’ve been teaching at

I’ve been teaching at