I.

I.

Are we always creating you, as Rilke said,

Trying, on our best days,

To make possible your coming-into-existence?

Or are you merely a story told in the dark,

A child’s drawing of barn and star?

Each year you are born again. It is no remedy

For what we go on doing to each other,

For history’s blind repetitions of hate and reprisal.

Here I am again, huddled in hope. For what

Do I wait? – I know you only as something missing,

And loved beyond reason.

As a word in my mouth I cannot embody.

II.

On the snow-dusted field this morning – an etching

Of mouse tracks declares the frenzy of its hunger.

The plodding dawn sun rises to another day’s

One warm hour. I’m walking to the iced-in local pond

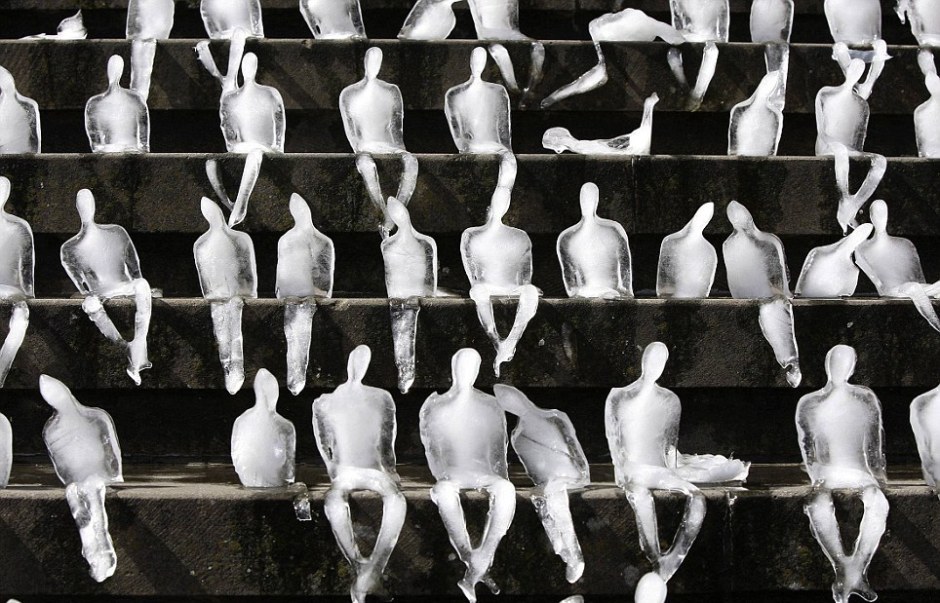

Where my neighbors have sat through the night

Waiting for something to find their jigged lure.

The sky is paste white. Each bush and tree keeps

Its cold counsel. I’m walking head-on into a wind

That forces my breath back into my mouth.

Like rags of black cloth, crows drape a dead oak.

When I pass under them, their cries rip a seam

In the morning. Last week a life long friend told me,

There’s no such thing as happiness. It’s ten years

Since he found his son, then a nineteen-year old

Of extraordinary grace and goodness, curled up

In his dormitory room, unable to rise, to free

Himself of a division that made him manic and

Depressed, and still his son struggles from day to day,

The one partial remedy a dismal haze of drugs.

My friend hopes these days for very little – a stretch of

Hours, a string of a few days when nothing in his son’s life

Goes terribly wrong. This is the season of sad stories:

The crippling accident, the layoffs at the factory,

The family without a car, without a house, without money

For presents. The sadder the human drama, the greater

Our hope, or so the television news makes it seem

With its soap-opera stories of tragedy followed up

With ones of good will – images of Santas’ pots filling up

At the malls, truckloads of presents collected for the shelters,

Or the family posed with their special-needs child

In front of a fully equipped van given by the local dealership.

This is the season to keep the less fortunate in sight,

To believe that generosity will be generously repaid.

We’ve strung colored lights on our houses and trees,

And lit candles in the windows to hold back the dark.

For what do we hope? – That our candles will lead you

To our needs? That your gift of light will light

These darkest nights of the year? That our belief

In our own righteousness will be vindicated?

The prophet Amos knew the burden of our coming.

The day of the Lord is darkness, he said, darkness, not light,

As if someone went into a house and rested a hand against a wall,

And was bitten by a snake. Amos knew the shame of

What we fail, over and over, to do, the always burning

Image of what might be. Saint Paul, too, saw

The whole creation groaning for redemption.

And will you intercede with sighs too deep for words

Because you love us in our weakness, because

You love always, suddenly and completely, what is

In front of you, whether it is a lake or leper.

Because you come again and again to destroy the God

We keep making in our own image. Will we learn

To pray: May our hearts be broken open. Will we learn

To prepare a space in which you might come forth,

In which, like a bolt of winter solstice light,

You might enter the opening in the stones, lighting

Our dark tumulus from beginning to end?

III.

All last night the tatter of sleet, ice descending,

Each tree sheathed in ice, and then, deeper

Into the night, the shattering cracks and fall

Of branches being pruned by gusts of wind.

It is the first morning after the longest night,

Dawn colorless, the sun still cloud-silvered.

Four crows break the early stillness, an apocalypse

Of raucous squawks. My miniature four horsemen

Take and eat whatever they can in the field

Outside my door: a deer’s leg my dog has dragged

Home. Above them, the flinty sun has at last fired

A blue patch of sky, and suddenly each ice-transfigured

Trees shines. Each needle of pine, each branch

Of ash, throws off sparks of light. Once,

A rabbi saw a spark of goodness trapped inside

Each evil, the very source of life for that evil –

A contradiction not to be understood, but suffered,

The rabbi explained, though the one who prays

And studies Torah will be able to release that spark,

And evil, having lost its life-giving source, will cease.

When I finally open my door and walk out

Into the field, every inch of my skin seems touched

By light. So much light cannot be looked at:

My eyelids slam down like a blind.

All morning I drag limbs into a pile. By noon,

The trees and field have lost their shine. I douse

The pile of wood with gas, and set it aflame,

Watching the sparks disappear in the sky.

IV.

This is the night we have given for your birth.

After the cherished hymns, the prayers, the story

Of the one who will become peacemaker,

Healer of the sick, the one who feeds

The hungry and raises the dead,

We light small candles and stand in the dark

Of the church, hoping for the peace

A child knows, hoping to forget career, mortgage,

Money, hoping even to turn quietly away

From the blind, reductive selves inside us.

We are a picture a child might draw

As we sing Silent Night, Holy Night.

Yet, while each of us tries to inhabit the moment

That is passing, you seem to live in-between

The words we fill with our longing.

The time has come

To admit I believe in the simple astonishment

Of a newborn.

And also to say plainly, as Pascal knew, that you will live

In agony even to the end of the world,

Your will failing to be done on earth

As it is in heaven.

Come, o come Emmanuel,

I am a ghost waiting to be made flesh by love

I am too imperfect to bear.

– Robert Cording, ‘Advent Stanzas’, in The Best American Spiritual Writing 2005 (ed. Philip Zaleski; Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2005), 18–22.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

Turning and turning in the widening gyre