Marc Chagall, 'The White Crucifixion', 1938

What does it mean to share Christ’s peace with each other?

Chapter 2 of Paul’s letter to the saints in Ephesus opens with an exposition of the lavish mercy and love of God by which we who were ‘dead in sin’ are made ‘alive with Christ’. Paul makes it clear that this divine action has been concerned to create a new entity in the world by which God brings blessing to the nations and through which God displays the glory of his grace to the principalities and powers in the heavenly realms. And Paul is concerned that we understand that this new reality to which the church bears witness is inseparably identified with Jesus Christ – that is, all we have and all we are and all we will ever be is now in Christ.

And then, from verses 11–22, Paul unpacks something of what it means to be in Christ. He talks about circumcision and uncircumcision. He talks about the commonwealth of Israel and about a new kind of citizenship. And he talks about the household of God and of a new temple in which God dwells by the Spirit. Now all of these things had deep connotations in the First Century, but this does not mean that they are confined to the First Century!

Like our own land, that of the regions around the Mediterranean during the First Century were made up of a vast number of culturally- and ethnically-diverse groups. But in all of that, there existed no greater cultural or religious divide as that between Jews and non-Jews (Gentiles) – a divide most obvious when it came to issues pertaining to the temple. Both groups had a different understanding of history and of where history is heading, a different understanding of who God is, a different understanding of revelation, a different understanding of worship, a different understanding of why we are here, a different understanding of how to live together as human community. And along with these different understandings was a deep hatred for one another that went both ways.

The Jew had an immense contempt for the Gentiles. The Gentiles, said the Jews, were created by God to be fuel for the fires of hell. God, they said, loves only Israel of all the nations he had made … It was not even lawful to render help to a Gentile mother in her hour of sorest need, for that would simply bring another Gentile into the world. Until Christ came, the Gentiles were an object of contempt to the Jews. The barrier between them was absolute. If a Jewish boy married a Gentile girl, or if a Jewish girl married a Gentile boy, the funeral of that Jewish boy or girl was carried out. Such contact with a Gentile was the equivalent of death. [William Barclay, cited in John R.W. Stott, God’s New Society: The Message of Ephesians (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1979), 91].

And for their part, the Gentiles viewed the Jews with attitudes that ranged from curiosity to perplexity to fierce persecution. Judea was not an easy place for Herod to rule. We don’t have time to go into all the background of this but what we do need to see is that the barriers between these two groups – like that between Serbs and Croats – were long-standing and, to human eyes, insurmountable.

We have, to our shame I think, gotten used to using adjectives to describe different Christians. So we talk about ‘Chinese’ Christians, or ‘Palangi’ Christians, or ‘born-again’ Christians, or ‘Catholic’ Christians, or ‘gay and lesbian’ Christians, as if what really unites us is not the fact that we are in Christ so much as it is our ethnicity, or our difference from others. And we’re not wanting to suggest that these adjectives aren’t true, or that they’re completely erased by the transformation that comes in Christ. But we do want to confess that in Christ, we are no longer defined, and still less separated, by them. So Paul to the Galatians:

… for in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith. As many of you as were baptised into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. (Gal 3:26–28)

Here too the issue pertains to our identity: Who are we? What is our relationship with – and obligation to – others? What might it mean when Paul says that ‘now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he is our peace; in his flesh he has made the two one and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility between us’? What does it mean that Jesus has taken our place of alienation? That in his cross, he became the prodigal? That he left the security of the Father’s house and went off into the far country? And in that far country, in the desert of his alienation, he gathered all of humanity to himself and reconciled us together and to God. He brought us home! He created one new ‘man’. What does it mean that he has taken responsibility for all that would compromise our relationship with God and with each other? And what might it mean that in his wounds he has healed all that separates man from man, and woman from woman, and tribe from tribe, and Jew from Gentile, and husband from wife, and child from parent, and you and I from God? What might it mean when Paul writes in Colossians 1 that …

God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross. (Col 1:19–20)

The peace created in Christ is more than just that which transcends ethnic divides. We also have to think about political and cosmic, moral and righteous, intellectual and psychological, physical and metaphysical walls as well. As one commentator has written:

Jesus Christ has to do with whatever divisions exist between races and nations, between science and morals, natural and legislated laws, primitive and progressive peoples, outsiders and insiders. The witness of Ephesians to Christ is that Christ has broken down every division and frontier between [human beings]. And even more, Ephesians adds that Christ has reconciled [humanity] with God!

To confess Jesus Christ is to affirm the abolition and end of division and hostility, the end of separation and segregation, the end of enmity and contempt, and the end of every sort of ghetto! Jesus Christ does not bring victory to the [person] who is on either this or that side of the fence. Neither rich nor poor, Jew nor Greek, man nor woman, black nor white, can claim Christ solely for [themselves]. [Markus Barth, The Broken Wall: A Study of the Epistle to the Ephesians (London: Collins, 1960), 37.]

So Bruce Hamill reminded the folk at Coastal Unity parish recently:

We belong to [Christ] … because he has made peace … not because he merely teaches us about peace, or preaches peace, or encourages peace, but because in his own body he has made peace and broken down the enmity … And the purpose of his life and death is to create a single new humanity in Christ – a humanity of peace … but a humanity which is peace in Christ.

And … the biggest barrier to this humanity of peace … is the thought that enmity must be killed by Christ … it is the thought that we need to have peace made for us first before we can make it ourselves. Most of us believe we can kill the enmity ourselves, if we think it exists at all. We are confident that we can make peace our self, even if it is only purifying our own attitude. In general we struggle to admit our need to have our old humanity killed, so that Christ can create us into a single new humanity. We find that demeaning! However, it is the beginning of the Christian life. Christianity begins with a death, (our death) or it doesn’t begin at all.

So to return to the question with which we began: What does it mean to share Christ’s peace with each other? And from here I draw upon Timothy Radcliffe’s superb book, Why God to Church?: The Drama of the Eucharist (pp. 161–74.) For many, the exchanging of the sign of peace can be embarrassing and awkward. We might offer a peck on the cheek to members of our family or to friends, but strangers are more likely to receive a distant nod or a polite handshake. But it was not always so.

During the Middle Ages the kiss of peace was a solemn moment of reconciliation in which social conflicts were resolved. The community was restored to charity before Holy Communion could be received. One of the earliest preaching missions entrusted to the Dominicans and Franciscans was what was called ‘The Great Devotion’ of 1233. Northern Italian cities were torn apart by division which in some cases amounted to civil war. And the climax of the preaching was the ritual exchange of the kiss of peace between enemies. Here at the table – in the eating of one loaf and the drinking of one cup – was enacted the reconciliation made real in Christ.

And here at the table, we confess that we Christians have often been unimpressive witnesses to Christ’s peace. Our history is marked by aggression, intolerance, rivalry and persecution. These days we usually avoid the extremes of some early Christians, rarely poisoning each other’s chalices or arranging ambushes of our opponents. But we still tend to succumb to the dominant ethos of our competitive and aggressive society, though rarely with the clarity of a First World War general who instructed his chaplain that he wanted a bloodthirsty sermon next Sunday ‘and would not have any texts from the New Testament’.

I want to suggest that when we offer each other a sign of peace we are not so much making peace as we are accepting and confessing the Christ who is our peace. To be a member of the Church is to share Christ’s peace, however nervous or awkward we may feel. I recall the challenging words of Thomas Merton: ‘We are already one. But we imagine that we are not. And what we have to recover is our original unity. What we have to be is what we are’. [Thomas Merton, The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton (ed. Patrick Hart, et al.; New York: New Directions Publishing, 1975), 308]

When we offer each other Christ’s peace we are doing no less than accepting the basis upon which we are gathered together. We recognise that we are here together not because we are friends or because we enjoy the chummy atmosphere, or because we have the same theological opinions, but because – and only because – we are one in Christ’s indestructible peace. That’s why we gather as church: to exchange the kiss of peace with strangers, to exchange the sign of our Lord’s victory in the face of all that assaults human community.

John records that on the evening of the resurrection, ‘the first day of the week, … the doors of the house where the disciples had met were locked for fear of the Jews, [and] Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you”’ (John 20:19). The disciples are locked in the upper room for fear of the Jews, and Jesus passes through the walls and doors erected by their fear and by doing so reveals the way in which the limitations of our present bodily communion are overthrown. If Jesus is shown as walking through locked doors then it is because he is the one in whom all barriers are transcended. God is love, and love does not love walls.

When a French Dominican celebrated a family funeral after WWII he saw that the congregation was deeply divided. On one side of the aisle were those who had belonged to the Resistance and on the other those who had collaborated with the Nazis. He announced that the funeral Mass would not even begin until the kiss of peace had been exchanged. This was a wall that had to fall before it would have made any sense to pray together for the resurrection of their dead brother. Hanging onto alienation is mortal. It is, in the words of Ann Lamott, like drinking rat poison and then waiting for the rat to die.

Jesus’ invitation to this table means his embrace of all the ways in which our communion is faulty, subverted or betrayed. Here, in bread and wine, he takes into his hands all our fear, betrayal, lies, cowardice, shame, pain, isolation, distances, silences, misunderstandings and disloyalties, saying, ‘This is my body, given for you’.

Together we sing for joy that Christ comes, that he returns to our midst in the Eucharist, to strengthen us in our struggles, to share with us the burden of each day, to speak to us of peace when our minds are troubled, and to put the hope of eternal life in our hearts in that hour when our way seems to be entering the shadow of death. Here again we see that in spite of the barriers we have erected, the Eucharist is a sacrament of unity, joining us all in the same triumphant joy that the presence of the risen Lord gives to his Church. [Jean-Daniel Benoît, Liturgical Renewal: Studies in Catholic and Protestant Developments on the Continent (ed. Geoffrey W. H. Lampe; trans. Edwin Hudson; Studies in Ministry and Worship; London: SCM Press, 1958), 16]

And so in this bread and wine, Christ is really present to us, even more present than we are to each other, more bodily. He is truly the embodied Word of God who pulls down every barrier. That’s what it means for him to say to us, ‘Peace be with you’. For him to be risen is, then, not just to be alive once more: it is to be the place of peace in whom we meet and are healed.

There’s one wee book of Hauerwas’ that I purchased during the past year and never got around to reading, namely Cross-Shattered Christ: Meditations on the Seven Last Words (Brazos Press, 2004). Lent seemed like the right time to dig in. So I found me a quiet moment tonight and read it. Here’s a few passages that I sat with for a while:

There’s one wee book of Hauerwas’ that I purchased during the past year and never got around to reading, namely Cross-Shattered Christ: Meditations on the Seven Last Words (Brazos Press, 2004). Lent seemed like the right time to dig in. So I found me a quiet moment tonight and read it. Here’s a few passages that I sat with for a while:

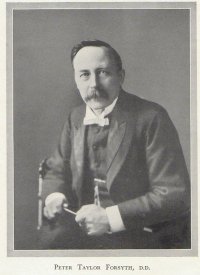

‘Sin … is not measured by a law, or a nation, or a society of any kind, but by a Person. The righteousness of God was not in a requirement, system, book, or Church, but in a Person, and sin is defined by relation to Him. He came to reveal not only God but sin. The essence of sin is exposed by the touchstone of His presence, by our attitude to Him. He makes explicit what the sinfulness of sin is; He even aggravates it. He rouses the worst as well as the best of human nature. There is nothing that human nature hates like holy God. All the world’s sin receives its sharpest expression when in contact with Christ; when, in face of His moral beauty, goodness, power, and claim, He is first ignored, then discarded, denounced, called the agent of Beelzebub, and hustled out of the world in the name of God’. – PT Forsyth,

‘Sin … is not measured by a law, or a nation, or a society of any kind, but by a Person. The righteousness of God was not in a requirement, system, book, or Church, but in a Person, and sin is defined by relation to Him. He came to reveal not only God but sin. The essence of sin is exposed by the touchstone of His presence, by our attitude to Him. He makes explicit what the sinfulness of sin is; He even aggravates it. He rouses the worst as well as the best of human nature. There is nothing that human nature hates like holy God. All the world’s sin receives its sharpest expression when in contact with Christ; when, in face of His moral beauty, goodness, power, and claim, He is first ignored, then discarded, denounced, called the agent of Beelzebub, and hustled out of the world in the name of God’. – PT Forsyth,

Sith my life from life is parted:

Sith my life from life is parted: Writing of Bacon, Locke and Scottish common sense philosophy (uncritically lumped together), Nevin writes: ‘The general character of this bastard philosophy is, that it affects to measure all things, both on earth and in heaven, by the categories of the common abstract understanding, as it stands related to simply to the world of time and sense’. – John W. Nevin,

Writing of Bacon, Locke and Scottish common sense philosophy (uncritically lumped together), Nevin writes: ‘The general character of this bastard philosophy is, that it affects to measure all things, both on earth and in heaven, by the categories of the common abstract understanding, as it stands related to simply to the world of time and sense’. – John W. Nevin,  In his brilliant treatment on forgiveness,

In his brilliant treatment on forgiveness,  sin of victimisation; and second, liberation as victims from the bitterness and hatred that attend the sense of irreversible injustice, the hurt of damaged lives, irretrievably lost opportunities, and all the other evils that result from sin. There is liberation here, he said, because precisely at the point where we cannot forgive our enemies the Gospel suggests that our sole representative, the sole priest of our confession, does what we cannot do – he stands in and forgives our victimisers for us and in our place as the One on behalf of the many – and then invites us to participate in the very forgiveness he has realised vicariously on our behalf. On these grounds we are not only permitted to forgive but obliged and indeed commanded to forgive others. Alan said, ‘Where we are not entitled to forgive, the crucified Rabbi is. And where we are unable to forgive, we are given to participate in his once-and-for-all forgiveness and to live our lives in that light and from that centre – not least in the political realm’. He cited his dad (JB Torrance), who defined worship as ‘the gift of participating by the Spirit in the Son’s communion with the Father’. The consequence of any ethic, therefore, that warrants the name ‘Christian’ must be conceived in parallel terms, namely as the gift of participating by the Spirit in the incarnate Son’s communion with the Father. ‘Forgiveness’, Alan stressed, ‘is the gift of participating in a triune event of forgiveness. In an act of forgiveness, the Father sends the Son, who, by the Spirit, forgives as God but also, by the Spirit, as the eschatos Adam on behalf of humanity. The mandate to forgive must be understood in this light.’

sin of victimisation; and second, liberation as victims from the bitterness and hatred that attend the sense of irreversible injustice, the hurt of damaged lives, irretrievably lost opportunities, and all the other evils that result from sin. There is liberation here, he said, because precisely at the point where we cannot forgive our enemies the Gospel suggests that our sole representative, the sole priest of our confession, does what we cannot do – he stands in and forgives our victimisers for us and in our place as the One on behalf of the many – and then invites us to participate in the very forgiveness he has realised vicariously on our behalf. On these grounds we are not only permitted to forgive but obliged and indeed commanded to forgive others. Alan said, ‘Where we are not entitled to forgive, the crucified Rabbi is. And where we are unable to forgive, we are given to participate in his once-and-for-all forgiveness and to live our lives in that light and from that centre – not least in the political realm’. He cited his dad (JB Torrance), who defined worship as ‘the gift of participating by the Spirit in the Son’s communion with the Father’. The consequence of any ethic, therefore, that warrants the name ‘Christian’ must be conceived in parallel terms, namely as the gift of participating by the Spirit in the incarnate Son’s communion with the Father. ‘Forgiveness’, Alan stressed, ‘is the gift of participating in a triune event of forgiveness. In an act of forgiveness, the Father sends the Son, who, by the Spirit, forgives as God but also, by the Spirit, as the eschatos Adam on behalf of humanity. The mandate to forgive must be understood in this light.’ Colin E. Gunton,

Colin E. Gunton,  Such wrestling means that whether expounding a key motif in Barth’s theology or fielding questions, Gunton reveals not only a deep indebtedness to Barth’s work, but also points of divergence. He is upfront in the first lecture: ‘Not everyone buys into Barth … I don’t, all the way along the line, as I get older I get more and more dissatisfied with the details of his working out of the faith … over the years I think I have developed a reasonable view of this great man who is thoroughly exciting and particularly, I can guarantee, if you do this course, that you will be a better theologian by the third year, whether or not you agree with him – he is a great man to learn to think theologically with’ (p. 10; see the prefaces to his

Such wrestling means that whether expounding a key motif in Barth’s theology or fielding questions, Gunton reveals not only a deep indebtedness to Barth’s work, but also points of divergence. He is upfront in the first lecture: ‘Not everyone buys into Barth … I don’t, all the way along the line, as I get older I get more and more dissatisfied with the details of his working out of the faith … over the years I think I have developed a reasonable view of this great man who is thoroughly exciting and particularly, I can guarantee, if you do this course, that you will be a better theologian by the third year, whether or not you agree with him – he is a great man to learn to think theologically with’ (p. 10; see the prefaces to his