Just after beginning to come somewhat to terms (I say ‘somewhat’ for with evil there can be no such arrangement) with the devastating and deadly powers unleashed in Cyclone Evan, we find ourselves again on this day stirred with rage, frustration, despair, lament and grief birthed by news of yet another mass shooting in the USA. It is timely (and sadly so) that I happen to be working on a book of essays on the Hebrew notion of tikkun olam (to mend the world). It is timely too that today my friend Rebecca Floyd drew my attention to two sermons by J. Mary Luti. The first, first preached after the tragic events of the massive Indian Ocean tsunami, and the second, an excerpt from a sermon on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, both speak to this week’s events. Here are a few snippets. From the first:

Just after beginning to come somewhat to terms (I say ‘somewhat’ for with evil there can be no such arrangement) with the devastating and deadly powers unleashed in Cyclone Evan, we find ourselves again on this day stirred with rage, frustration, despair, lament and grief birthed by news of yet another mass shooting in the USA. It is timely (and sadly so) that I happen to be working on a book of essays on the Hebrew notion of tikkun olam (to mend the world). It is timely too that today my friend Rebecca Floyd drew my attention to two sermons by J. Mary Luti. The first, first preached after the tragic events of the massive Indian Ocean tsunami, and the second, an excerpt from a sermon on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, both speak to this week’s events. Here are a few snippets. From the first:

We Christians sometimes find it hard to refrain from overwhelming great empty spaces and terrifying silences with hope-filled murmuring about God’s love and abiding presence. We are people who count the resurrection as the core of our faith. For us, hope is second nature, nothing is impossible, death is not the end. But there are times when Easter comes too quickly, when we get Jesus off the cross and into glory with unseemly dispatch. Perhaps this haste is a reason why Easter is doubted by so many.

There are times when the God of the lilies of the field and of all our carefully-counted hairs must repulse us. Times when, in the face of the vulgar horrors of our world and the intimate tragedies of our lives, an all-caring God is inadequate. Times when light is premature, when it hurts our eyes and does not heal. Times when we need the cover of night.

Sooner or later, we all wonder with Job why we were ever born. Sooner or later, we all pore over the lexicon for a word with which to fashion inconsolable laments—and we find the cross, Christianity’s most believable symbol. It offers no answers. It offers instead a common lot: sooner or later life deposits us all at the cross. It is the gathering place for the world’s sorrow, its wasted efforts, its tormented children, its unimaginable catastrophes, and its utter silences. When we arrive at its foot, we also discover its hope – not the hope of Easter, but the hope that comes simply from having a place to gather when the pain is unspeakable and the sorrow beyond all bearing.

It is not yet the dawn. Not yet. We need to be healed, and we will be, but not too fast. We have to wait. It takes time. And we have to stay together, with every loss and horror creation has ever borne. We have to stay together so that it is not too frightening to wait, so that our waiting does not become despair. Like that inconsolable man in Indonesia, we may even prefer to wait, just as long as we are not alone. Together we will outwait death and come startled and blinking to Easter.

But no, not now. Not yet.

And from the second:

And from the second:

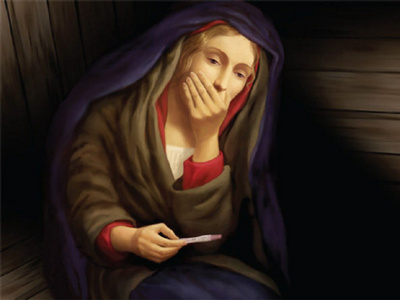

She will not be comforted. There is no way to address a grief like Rachael’s, and she stubbornly refuses everyone who tries. She refuses, in other words, to have the unspeakable reality of innocent suffering diminished in any way by attempts to assuage or explain it. Rachael is a witness to the things in human life that are so awful that they cannot be addressed, explained or repaired. They can only be wept over, lamented, mourned.

Rachael, in her single keening voice gives voice to all the keening mothers of Bethlehem’s babies, and to the un-voiceable anguish of every parent, family, clan and nation from whom children have ever been torn away and destroyed by a police state, by Jim Crow or apatheid, by political greed and indifference, by the glorification of war, by random violence, or by crushing poverty. Rachael will not be hushed about these things. She will not be pacified.

But we are surrounded by hushing, pacifying voices — knowing voices that explain and justify the unfortunate necessity of innocent suffering, as if it happens all by itself without human complicity: Guns don’t kill people … Cool voices that cover up or prettify what violence actually does. False voices that paint a sanctified picture of the meaning of suffering. Pragmatic voices of tyrants. Pandering voices of politicians. Patriotic voices of presidents and generals. Blaming voices of the self-made. Aloof, pious voices (God help us!) too often of the church.

At the start of a new year, especially one that will almost certainly see at least one new war unleashed on this gasping planet, the stubborn wail of Rachael weeping for her children urges us to resist and to refuse those false voices of explanation, rationalization, justification, and obfuscation of all the things that are just not right and which must not be condoned.

Rachael’s grief, never to be comforted, urges us also to rip apart with our own lamentation (and our own repentance) the curtain behind which hides the greatest lie – that it just can’t be helped, that we have no choice but to stand by and accept the suffering of the innocent, the enslavement and destruction of the future. For the stuff of her life is the stuff of ours: the murder of innocents, whether it be lives destroyed in office buildings in New York, hospitals with inadequate supplies in Iraq, famine in Ethiopia, orphanages in Rwanda, school buses in Tel Aviv, a shot-up elementary school in your small town, or razed homes in the little town of modern Bethlehem.

When Rachael makes her brief appearance on the Christmas stage; when this wailing mother of a dead child shows up beside a sleeping child watched over by a virgin tender and mild, we are also reminded, thankfully, that what human words cannot speak of adequately or truthfully, God’s Word, the word we experience in Jesus, can.

The babe who escaped this time, the child whom one Herod could not find, but who will be found by another Herod in thirty-three years’ time and will not escape him then — this child is God’s final Word to our world. It is a Word of comfort Rachael might finally accept, for it is a Word of justice. A Word from a Voice clear and true, a ‘yes’ profound enough and persevering enough (through trial, cross and grave) to address whatever horrific stuff our living and dying, our ignorance, sin and fear can present.

Now and forever it is spoken powerfully against the powers-that-be, defeating death itself — even ours, if we follow its resonance and welcome its light.

And my friend Bruce Hamill has penned the following prayer for tomorrow’s church service:

Today we pray for a society obsessed with weapons of destruction and sometimes mass destruction, obsessed with self-defence and the perpetuation of violence. We pray for America and we pray for our own country inasmuch as we share the same cultural patterns and values. Lord we lament with your people everywhere, how much we have talked of the gospel but failed to appreciate the gospel of peace, replacing it with a gospel of personal security and individual salvation. We have failed you. Have mercy and bring your judgement first to the household of God. If we do not bear witness to the gospel of peace, who will? Lord have mercy on us.

At times like these, however, I often find myself both reflecting on Keiji Kosaka’s profound sculpture ‘Reconciliation in the Midst of Discontinuity’, and turning to both Donald MacKinnon and to Gillian Rose, and to their efforts, each in their own way, to resist premature closure of what must remain open and patient and in agony. MacKinnon’s reflection on John 1.10–11 (‘He was in the world and the world took its origin through him and the world did not know him. He came to what was his own and his own people did not receive him’) provides one such example of what I mean. Here’s an excerpt::

At times like these, however, I often find myself both reflecting on Keiji Kosaka’s profound sculpture ‘Reconciliation in the Midst of Discontinuity’, and turning to both Donald MacKinnon and to Gillian Rose, and to their efforts, each in their own way, to resist premature closure of what must remain open and patient and in agony. MacKinnon’s reflection on John 1.10–11 (‘He was in the world and the world took its origin through him and the world did not know him. He came to what was his own and his own people did not receive him’) provides one such example of what I mean. Here’s an excerpt::

It is sheer nonsense to speak of the Christian religion as offering a solution of the problem of evil. There is no solution offered in the gospels of the riddle of Iscariot through whose agency the Son of man goes his appointed way. It were good for him that he had not been born. The problem is stated; it is left unresolved, and we are presented with the likeness of the one who bore its ultimate burden, and bore it to the end, refusing the trick of bloodless victory to which the scoffers, who invited him to descend from his cross, were surely inviting him.

What the gospels present to us is the tale of an endurance. “Christ for us became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross.” The writer of the fourth gospel invites his readers to find in the tale of this endurance the ultimate secret of the universe itself. For the ground of that universe is on his view to be identified with the agent of that endurance. So his teaching cannot easily be qualified as optimistic or pessimistic. He is no pessimist; for he is confident that we can find order and design, the order and design of God himself, in the processes of the universe and in the course of human history. But if men would understand that design, they must not, in random speculative mood, look away from the concrete reality of Jesus of Nazareth, from the bitter history of his coming and rejection. Where the speculative intellect finds answer to its furthest ranging questions is still the same place where the bruised spirit may find consolation from the touch of a man of sorrows.

To suggest that Christianity deals with the problem of evil by encouraging the believer to view it from a cosmic perspective is totally to misunderstand both the difficulty and the consolation of its treatment. Rather Christianity takes the history of Jesus and urges the believer to find, in the endurance of the ultimate contradictions of human existence that belongs to its very substance, the assurance that in the worst that can befall his creatures, the creative Word keeps company with those whom he has called his own. “Is it nothing unto you all ye that pass by? Behold and consider whether there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.” It is not as if the passer-by were invited immediately to assent to the proposition that there was indeed no such sorrow; he is asked to “consider”. It is a profound mistake to present the Christian gospel as if it were something that immediately showed itself, that authenticated itself without reflection. It is of the manner of the coming of Jesus that he comes so close to the ordinary ways of men that they hardly notice him, that they treat him as one of themselves. “There stands one among you whom you know not”: so the Baptist in that same first chapter of John to which I have so often referred. But how, except by coming so close to men, could he succour them? A Christ who at the last descended from the cross must leave the penitent robber without the promise of his company in paradise; and such a Christ we may dare say must also deprive himself of the precious comfort in his own extremity that he received from the gangster beside him; for it was that gangster who in Luke’s record continued with him to the very end of his temptation.

I am not here offering an apologetic, only bringing out certain elements in the complex reality of Christianity that seems to me of central importance. I would say that nobody these days, who is concerned at all with issues of faith and unbelief, can afford to treat them as opportunities for being clever. If men still believe – in spite of the strong, even overwhelming, case of the sceptic – it must be because they find malgré tout in Christianity the revelation of the eternal God, a revelation that touches them in the actual circumstances of their lives, whether in the common fear of a week of international crisis, or in the more personal extremities of sin, failure, bereavement, of unresolvable conflict of obligations when they find themselves pulled in two directions by claims of pity and by claims of truth. Is the so-called gospel in any sense good news to one who has bestowed love and care upon another whom he is forced in obedience to the claims of truth to acknowledge as worthless and corrupt? If it has no word of consolation in such extremity, how can we call it good news to the individual? What value is there in a cosmic optimism which leaves unplumbed the depths of human grief?

So I come back to the place where nearly I began, to the figure prostrate on the ground praying that the hour might pass. It is the claim of Christianity that men find God there, that in some sense all who came before that one were thieves and robbers, that he indeed it is in whom all things consist, through whom they take their origin, and by whom they will find their consummation. Men may well find in the end that this claim is beyond their acceptance, that it demands assent to what they cannot, if they are honest, say yes to. But those who believe its truth as long as indeed they do believe it must at least make sure that what is rejected is the substantial reality and not a counterfeit bereft alike of pity and of glory.

It may seem strange that I have gone so far without even mention of the Resurrection; but my reticence in this respect is of design. In one sense belief that Jesus was raised from the dead, that the Father pronounced a final Amen to his work, is a prius of my whole argument. To discuss the issue of the historical evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus and the complex theological problems that it raises would take me beyond the limitations I have deliberately imposed upon myself. Yet it is the prius of my whole argument; for it is in the Resurrection that we find the ultimate source of that peculiar tension between optimism and pessimism which I have judged characteristic of Christianity. One thing, however, in conclusion, I would dare to say, and that is this. It is a commonplace of traditional theology that in speech concerning God and the things of God “the negative way” must precede “the way of eminence”. If men would give sense to what they say, they must be agnostic before they dare invoke the resources of anthropomorphic imagery; they are always properly more confident concerning what they must deny than concerning what they may affirm. So with what men intend when they speak of the Resurrection of Jesus; they know what it is not in a way in which they cannot know what it is, inasmuch as its ultimate secret rests with the Father who raised him.

In knowing what it is not, they know that it is not a descent from the cross postponed for thirty-six hours. It is not the sudden dramatic happy ending which the producer of a Hollywood spectacular might have conceived. In the stories as we have them, it is only to his own that the risen Christ shows himself with the marks of his passion still upon him; his commerce with them is elusive and restricted, as if to guard them against the mistake of supposing that they were witnesses of a reversal, and not of a vindication, of those things which had happened. It is a commonplace of theology to speak of the Resurrection as the Father’s Amen to the work of Christ; yet it is a commonplace to whose inwardness writers on the subject often attend too little. For if it does anything, it drives one back to find the secret of the order of the world in what Christ said and did, and the healing of its continuing bitterness in the place of his endurance.

“Come down from the cross and we will believe.” Many Christians have joined in this cry; many continue indeed to make it their own, even when they pay lip service to the gospel of the Resurrection. But it is only in the light of the Resurrection that those Christians can learn rather to say with understanding the profound words of Pascal, that Christ will indeed be in agony unto the end of the world.

With so many worthy entries, it was a tough gig indeed to decide on a winner for this year’s Advent Caption Competition. But after much anguish and discussion, and with some sortition and bribery, I am delighted to announce that this year’s winner is Brad Guderian with his caption, ‘What’s it mean when there’s a little cross on this thingy?’ Brad gets to choose one of the following titles:

With so many worthy entries, it was a tough gig indeed to decide on a winner for this year’s Advent Caption Competition. But after much anguish and discussion, and with some sortition and bribery, I am delighted to announce that this year’s winner is Brad Guderian with his caption, ‘What’s it mean when there’s a little cross on this thingy?’ Brad gets to choose one of the following titles: