‘By great care in his (sic) selection. I do not mean merely care as to his ability and character. I mean care that he is one who increases your own faith and ministers to your own soul. It is fatal to our Protestant principle to vote for a minister because you can just tolerate him yourself, but think he will be of great use among the young or in the town. The minister is first and foremost minister to your faith; and he will not feel that he gets from you what he needs unless he feel also that you are united in the bond of a growing faith and love. Select your minister for yourself, and not for your neighbour.

‘By great care in his (sic) selection. I do not mean merely care as to his ability and character. I mean care that he is one who increases your own faith and ministers to your own soul. It is fatal to our Protestant principle to vote for a minister because you can just tolerate him yourself, but think he will be of great use among the young or in the town. The minister is first and foremost minister to your faith; and he will not feel that he gets from you what he needs unless he feel also that you are united in the bond of a growing faith and love. Select your minister for yourself, and not for your neighbour.

Let him feel that his ministry is a real factor in the reasons which lead you to live where you do. What help can you give to the minister’s work and soul if he feels that you are ready to remove to the other side of the town for better tennis, a better golf–course, or for a change merely? It is amazing that Christian people should take a house without any inquiry what the neighbourhood offers a family in the way of religious advantage. When men complain that they cannot hold their family to their faith because there is no church near they can profit by, whose fault is that?

Represent to him that it is unnecessary for him to attend every meeting held in connection with the church, that to be out most nights at such meetings is mischievous to next morning’s study, and that he cannot hope to be the blessing to his people that he might be if Sunday arrive simply at the close of a jaded week. Do not forget that what starts you on a new week is for him the end of a stale one, so far as nervous condition goes.

Tell him when he first comes to see you that it will make no difference to your sympathy or your Sunday attendance if he never comes to see you at all except in some crisis. You stand some chance then of being the best–visited family in the congregation.

Tell his wife the same thing, especially if she have a family of children.

Send him a note when the sermon has done you special good; and add that if he answer it, you will not send another.

But if a text trouble you, or a problem, put it in black and white, and say that if he is at a loss for a subject at any time, you would be grateful if he would take that, or would let you talk to him about it.

Use your opportunity to practise local preaching and the conduct of a service. Few things carry home to the pew so well as that what it means to be in the pulpit every Sunday. The minister has this reason of his own for wishing that all the Lord’s people were prophets. Besides, it is a great thing for a minister to know that he preaches to preachers, and is giving to givers. If you have a class, treat it not only as a teacher, but also as a pastor. Have a care of souls. That will open your eyes a little to what pastoral concern is. Faults and failings which to an outsider are mere matter of curiosity are to the pastor an anxiety and grief. You will help him to carry it if you know by experience what this divine concern is, if you have souls you watch for, and lives you train for Christ. Your family may teach you this pastoral sympathy if no other sphere does. Do not omit or neglect this pastoral office at home, as the manner of so many is. It casts on the minister a burden he was never meant to bear. The father is the true pastor of the young. You have no right to blame the minister for the indifference of your young people unless he is palpably incompetent, or worse. It seems to me sometimes that the congestion of work thrown on the church, the dispersion of its energies over trivial efforts to catch youth, the oppressive distraction of the minister, all have their root in the general neglect of family religion. The church and the minister are called on for work which God never meant should be done by the church at all, but by the home. The church is but one organ of the Kingdom of God, and the home is another. And we know what happens when a vital organ refuses work and throws a long strain on another. The end is weakness, illness and death.

Bring to church affairs business methods, but not the business spirit. A Church Meeting is not a committee, nor is it a political assembly. It is the sphere neither of criticism nor of mere discussion, but of Christian work and fellowship in faith and love. Let all truth–telling be the telling of the truth as it is in Jesus.

When the minister asks you to do something, do it without excuses, and without deprecating yourself as compared with someone else. If you wish to escape being asked, do what you are asked and let your unfitness be proved. People will not believe it till you convince them. Then you will have peace.

Do not ask him and his wife to tea “and spend the evening”. At least, do not regard it as part of his ministerial work.

Insist that he be punctual in keeping engagements, answering letters, and especially in beginning service. You can sometimes see the whole secret of an ‘ineffectual ministry in the ten minutes after the hour at which worship should begin. A man who is systematically late at public meetings loses more influence than he knows. How can he hope to be effective with business people whom he exasperates to begin with? Besides, it is an offensive liberty to take.

Insist that he be punctual in keeping engagements, answering letters, and especially in beginning service. You can sometimes see the whole secret of an ‘ineffectual ministry in the ten minutes after the hour at which worship should begin. A man who is systematically late at public meetings loses more influence than he knows. How can he hope to be effective with business people whom he exasperates to begin with? Besides, it is an offensive liberty to take.

It might help him if he thought there were the occasional risk of a deacon calling on some pressing business at 9 a.m.

If you are absent from church, let it be when he is there, not when he goes away. The minister supplying finds and reports abroad a poor congregation. It is gauche flattery to say to your minister you only miss when he does.

It would be a help to some if you made it understood, in some kind way, that the minister’s speech at a social meeting need not always be funny, so long as it was sunny.

Do not omit to thank him for asking a subscription. They do you a true service who suggest to you, or collect from you what it is your duty to find means to give. Let him know that when he has a case of real need, he may always reckon on you according to your power. Few things are more disagreeable to most ministers than to ask for money. Remember, those who ask you for Christian money are your agents, not your duns.

Make it clear that you have a higher respect for the office of the ministry than even for the man who fills it. A minister who holds his place only in the affection of his own people carries a too heavy burden; it puts too much of the responsibility upon his personal qualities alone. After all, the church is more than the minister, and the apostolic office is more than the idiosyncrasy of its occupant. No minister should be encouraged to think that he improves his position or usefulness by what doctors or lawyers would call unprofessional or undignified conduct, or by any course that lowers the standard of his office. Your minister, to be sure, needs sympathy, and he must have it; for with us the whole ministerial bond is dissolved when sympathy ceases between pulpit and pew, and divorce should quickly ensue. But there is something that the true minister craves more than sympathy with his person, and that is sympathy with his gospel. “I believe in you, but I don’t believe in your truth,” is no Christian relation. It is mere personal friendship, and the minister must have a higher aim than being his people’s friend; he must be their guide, teacher, and at need corrector. When he is appointed, he is appointed to this. He is not merely the representative of his own community, he is a representative of the whole Church and a special trustee of what Christ committed to the Church. He must speak sometimes to his own church in the name of the Church universal and invisible. You should help to protect him from a frame of mind that overlooks this or makes it impossible. You will lose as well as he if he become parochial or conventialist, if he be a mere prophetic individualist and make nothing of his office. A freelance may rouse and pique, but a lance of any kind is very apt to wound, especially when it is nothing but free.

The old–fashioned advice, “Pray for your minister”, is never out of date. I would only press it into detail.

Pray with him–i.e. let your private prayers include what is most on his heart.

Pray for him–not generally, but in detail. Realize his position by an act of imaginative sympathy, and pray for the special things you divine he needs.

It may help him even more if you really and privately study your Bible. The minister is hampered by his people’s ignorance of their Bible more than by most things. It is a joy and a power to minister to a people exercised in the Bible and hungry for its light. The more you pray over your Bible, the more you pray with and for your minister. You both work with the same textbook. What must it be for the teacher when the class is habitually unprepared?

It may help him even more if you really and privately study your Bible. The minister is hampered by his people’s ignorance of their Bible more than by most things. It is a joy and a power to minister to a people exercised in the Bible and hungry for its light. The more you pray over your Bible, the more you pray with and for your minister. You both work with the same textbook. What must it be for the teacher when the class is habitually unprepared?

The more you do to help your minister, the more he will feel, if he is of the right sort, that he is there to help you rather than to be helped by you. He comes not to be ministered unto, but to minister. Your help will be abundantly returned to you. Help his gospel if you would have him help your soul. But if you go on neither really helping the other, then God help you both!’

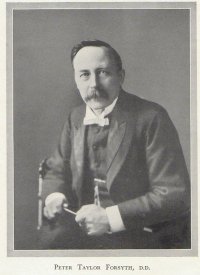

– PT Forsyth, ‘How to help your minister’, in Revelation Old and New: Sermons and Addresses (ed. John Huxtable; London: Independent Press, 1962), 115-19.

[Editorial note: I have left unchanged Forsyth’s non-inclusive language. He was a person of his time after all, a truth evident not only in terms of grammar but also in terms of the shape that pastoral ministry took, and the way the home was understood. Still, there is enough truth and meat in this short piece to encourage and challenge pastors and pastored alike.]

Regular readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem can gear themselves up for some more Forsyth in the next few posts. Here’s a few nuggets from his 1914 essay, ‘Christianity and Society’ (Methodist Review Quarterly):

Regular readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem can gear themselves up for some more Forsyth in the next few posts. Here’s a few nuggets from his 1914 essay, ‘Christianity and Society’ (Methodist Review Quarterly):

‘Sin … is not measured by a law, or a nation, or a society of any kind, but by a Person. The righteousness of God was not in a requirement, system, book, or Church, but in a Person, and sin is defined by relation to Him. He came to reveal not only God but sin. The essence of sin is exposed by the touchstone of His presence, by our attitude to Him. He makes explicit what the sinfulness of sin is; He even aggravates it. He rouses the worst as well as the best of human nature. There is nothing that human nature hates like holy God. All the world’s sin receives its sharpest expression when in contact with Christ; when, in face of His moral beauty, goodness, power, and claim, He is first ignored, then discarded, denounced, called the agent of Beelzebub, and hustled out of the world in the name of God’. – PT Forsyth,

‘Sin … is not measured by a law, or a nation, or a society of any kind, but by a Person. The righteousness of God was not in a requirement, system, book, or Church, but in a Person, and sin is defined by relation to Him. He came to reveal not only God but sin. The essence of sin is exposed by the touchstone of His presence, by our attitude to Him. He makes explicit what the sinfulness of sin is; He even aggravates it. He rouses the worst as well as the best of human nature. There is nothing that human nature hates like holy God. All the world’s sin receives its sharpest expression when in contact with Christ; when, in face of His moral beauty, goodness, power, and claim, He is first ignored, then discarded, denounced, called the agent of Beelzebub, and hustled out of the world in the name of God’. – PT Forsyth,

Defying empirical definition, holiness, like Christianity itself, only makes sense from the inside, from direct experience and that not only of hearing the seraphim calling to one another ‘Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts’, not even when such confrontation brings the self-revelation of personal and corporate uncleanness. Holiness comes home in that action when the same ‘LORD of hosts’ calls one of those seraphim to fly towards you with a live coal in its hand which he had taken with tongs from the holy altar and place that coal at the very source of one’s unholiness and say, ‘Behold, this has touched your lips; your guilt is taken away, and your sin forgiven’ (Isa 6:7).

Defying empirical definition, holiness, like Christianity itself, only makes sense from the inside, from direct experience and that not only of hearing the seraphim calling to one another ‘Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts’, not even when such confrontation brings the self-revelation of personal and corporate uncleanness. Holiness comes home in that action when the same ‘LORD of hosts’ calls one of those seraphim to fly towards you with a live coal in its hand which he had taken with tongs from the holy altar and place that coal at the very source of one’s unholiness and say, ‘Behold, this has touched your lips; your guilt is taken away, and your sin forgiven’ (Isa 6:7). ‘There is only one thing that can satisfy the holiness of God, and that is holiness – adequate holiness … Nothing, no penalty, no passionate remorse, no verbal acknowledgment, no ritual, can satisfy the claim of holy law – nothing but holiness, actual holiness, and holiness upon the same scale as the one holy law which was broken. The confession must be adequate … All your repentance, and all the world’s repentance, would not be adequate to satisfying, establishing the broken law of holy God. Confession must be adequate – as Christ’s was. We do not now speak of Christ’s sufferings as being the equivalent of what we deserved, but we speak of His confession of God’s holiness, his acceptance of God’s judgment, being adequate in a way that sin forbade any acknowledgment from us to be. For the only adequate confession of a holy God is perfectly holy man. Wounded holiness can only be met by a personal holiness upon the scale of the race, upon the universal scale of the sinful race, and upon the eternal scale of the holy God who was wounded. It is not enough that the eternal validity of the holy law should be declared as some prophet might arise and declare it, with power to make the world admire, as the great and sublime Kant did. It must take effect’. – PT Forsyth,

‘There is only one thing that can satisfy the holiness of God, and that is holiness – adequate holiness … Nothing, no penalty, no passionate remorse, no verbal acknowledgment, no ritual, can satisfy the claim of holy law – nothing but holiness, actual holiness, and holiness upon the same scale as the one holy law which was broken. The confession must be adequate … All your repentance, and all the world’s repentance, would not be adequate to satisfying, establishing the broken law of holy God. Confession must be adequate – as Christ’s was. We do not now speak of Christ’s sufferings as being the equivalent of what we deserved, but we speak of His confession of God’s holiness, his acceptance of God’s judgment, being adequate in a way that sin forbade any acknowledgment from us to be. For the only adequate confession of a holy God is perfectly holy man. Wounded holiness can only be met by a personal holiness upon the scale of the race, upon the universal scale of the sinful race, and upon the eternal scale of the holy God who was wounded. It is not enough that the eternal validity of the holy law should be declared as some prophet might arise and declare it, with power to make the world admire, as the great and sublime Kant did. It must take effect’. – PT Forsyth,  Forsyth consistently asserts that the Church’s faith rests not on some ‘subjective sanctity’ but on a ‘real principle’ – the objective work of Christ. This faith finds personal expression in his own experience of grace: ‘God has made life out of my shipwreck’, he says in his sermon on Ezekiel 37, ‘that is my experience. He has opened my grave and made me live; he has clothed my bones with flesh, and stirred me with life and hope; and if he has done that for me, then the incredible miracle is in principle done that saves the world.’ Here Forsyth gives voice to his conviction that he has been saved by that which saved the whole world. ‘It took a world salvation to save me, and what I know in this matter for me I foreknow for mankind.’ In other words, Forsyth is certain of his salvation because God has saved the world.

Forsyth consistently asserts that the Church’s faith rests not on some ‘subjective sanctity’ but on a ‘real principle’ – the objective work of Christ. This faith finds personal expression in his own experience of grace: ‘God has made life out of my shipwreck’, he says in his sermon on Ezekiel 37, ‘that is my experience. He has opened my grave and made me live; he has clothed my bones with flesh, and stirred me with life and hope; and if he has done that for me, then the incredible miracle is in principle done that saves the world.’ Here Forsyth gives voice to his conviction that he has been saved by that which saved the whole world. ‘It took a world salvation to save me, and what I know in this matter for me I foreknow for mankind.’ In other words, Forsyth is certain of his salvation because God has saved the world.