While in the current of writing a lecture on the Eucharist, I have been enjoying intincting – and, in some cases, re-intincting – into some great books: William T. Cavanaugh’s Torture and Eucharist: Theology, Politics, and the Body of Christ, Angel F. Mendez Montoya’s The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist, Stephen Sykes’ Power and Christian Theology, among them. William Stringfellow’s essay ‘Liturgy as Political Event’ is also wonderful. I’m also enjoying George Hunsinger’s The Eucharist and Ecumenism: Let Us Keep the Feast, a book that deserves a very close read and is certainly among the boldest and most important studies available on the subject.

While in the current of writing a lecture on the Eucharist, I have been enjoying intincting – and, in some cases, re-intincting – into some great books: William T. Cavanaugh’s Torture and Eucharist: Theology, Politics, and the Body of Christ, Angel F. Mendez Montoya’s The Theology of Food: Eating and the Eucharist, Stephen Sykes’ Power and Christian Theology, among them. William Stringfellow’s essay ‘Liturgy as Political Event’ is also wonderful. I’m also enjoying George Hunsinger’s The Eucharist and Ecumenism: Let Us Keep the Feast, a book that deserves a very close read and is certainly among the boldest and most important studies available on the subject.

Hunsinger notes that Thomas Aquinas, who was among the most impressive of the pre-Reformation theologians, understood the role of the priest in the eucharist as in some sense mediating between Christ and the faithful. In other words, for Thomas, the priest was the central figure in the eucharistic sacrifice. So Hunsinger writes: ‘‘He [i.e., the priest] acted both “in the person of Christ” (in persona Christi) as well as “in the person of the church” (in persona ecclesiae) (ST 3.82.8). In the person of Christ, he consecrated the sacrament. In the person of the church, he offered Christ in prayer to God (ST 3.82.8). Whatever the priest did when acting in the person of Christ was taken up in turn by the people (ST 3.83.4). The priest’s union with Christ, however, was different than it was for the laity. “Devout layfolk are one with Christ by spiritual union through faith and charity,” explained Aquinas, but the priest was one with Christ “by sacramental power” (ST, 3.82.1). At his ordination the priest had received a special status, “the power of offering sacrifice in the church for the living and the dead” (ST 3.82.1). The priest was set apart from the people, and above them, by virtue of this sacramental power’ (pp. 114–5).

Luther, of course, would radically qualify – or extend – this notion in his argument that the priest symbolised the priesthood of all believers, while possessing no special powers of consecration and sacrifice in and of himself. Luther stated:

‘Thus it becomes clear that it is not the priest alone who offers the sacrifice of the mass; it is the faith which each one has for himself. This is the true priestly office, through which Christ is offered as a sacrifice to God, an office which the priest, with the outward ceremonies of the mass, simply represents. Each and all are, therefore, equally priests before God . . . For faith must do everything. Faith alone is the true priestly office. It permits no one to take its place. Therefore all Christian men are priests, all women are priestesses, be they young or old, master or servant, mistress or maid, learned or unlearned. Here there is no difference unless faith be unequal’. Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 35: Word and Sacrament 1 (ed. J.J. Pelikan, et al.; vol. 35; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 100–1.

Hunsinger, in Eucharist and Ecumenism, properly notes that Luther upheld the idea of grace alone by combining christological mediation with communal participation:

‘The believer and the community can be said to offer Christ by participating in Christ’s own self-offering, which in turn mediates them into eternal life with God. Inclusion in Christ’s priestly self-offering is at once the promise and the consequence of grace. At the same time, the place of the priest in the mass has been radically redefined. Christ the eternal priest does not operate in and through the visible priest, nor does the priest offer Christ as the invisible victim through the bread and the cup. The bread and the cup, for Luther, are the sacramental but not the sacrificial body and blood of Christ. That is, they are not the means of reciprocal self-offering to God by Christ, priest, and people. They are not the eucharistic means by which Christ is offered up. The bread and cup are simply a pledge of Christ’s faithfulness to his promises. It is not the priest but the faith of each believer that offers Christ to God. The role of the priest is simply to symbolize by outward ceremonies the one true priestly office, which is faith’. (p. 135)

The Reformed, following Calvin and the best of those who spoke in his wake, sought to witness to how the cross and the eucharist are held in a unity that does not violate but reinforces their distinction via two forms: The constitutive form is the cross while the mediating form is the eucharist. ‘The cross is always central, constitutive, and definitive, while the eucharist is always secondary, relative, and derivative. The eucharistic form of the one sacrifice does not repeat the unrepeatable, but it does attest what it mediates and mediate what it attests. What it mediates and attests is the one whole Jesus Christ, who in his body and blood is both the sacrifice and the sacrament in one. As the sacrifice, he is the Offerer and the Offering. As the sacrament, he is the Giver and the Gift. The Son’s sacrificial offering of himself to the Father for us on the cross is the ground of the Father’s sacramental gift of his Son to the faithful in the eucharist’ (Ibid. 151). As TF Torrance has shown in Theology in Reconciliation, the cross is the ‘dimension of depth’ in the eucharist. The eucharist has no significance in and of itself. Its significance is both derived and grounded in the cross. The cross alone is, as TF Torrance notes, the saving ‘content, reality and power’ of the eucharist. It is to this that the Reformed minister and church directs our gaze.

It was precisely such a position which led PT Forsyth, the theologian of the cross, in his lectures on The Church and the Sacraments, to offer the following statement:

The Lord’s Supper is the most complete and plenary of all the cultic ways of confessing the work of reconciliation, where the sin of humanity is conquered by the grace of God in a holy Kingdom. It is therefore the real centre of the Church’s common and social life. This should not be sought in social reunions, or ecclesiastical monarchy, or philanthropic cohesion, but in the spiritual region, in the worship, and the theology moulding it. For here we are summoned to what is our vital centre deep within all the individual wills that wish to unite, to what is the centre of the faith that makes the new Humanity, and to the goal which rounds all’. (p. 260)

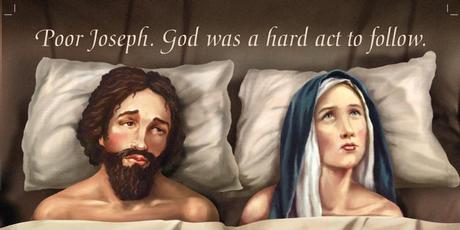

Happy Christmas to all readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem. Here’s PT Forsyth singing his constant song, and reminding us again of why today the Church might sing Joy to the World, and of the ‘wonders of [God’s] love’ :

Happy Christmas to all readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem. Here’s PT Forsyth singing his constant song, and reminding us again of why today the Church might sing Joy to the World, and of the ‘wonders of [God’s] love’ :