- Podcasts of William Lane Craig on Searching for the Historical Jesus and of William Lane Craig and Shelly Kagan on Is God Necessary for Morality?.

- Ernst Troeltsch and the resurrection: an Easter sermon by Kim Fabricius.

- A new book on Karl Barth: The Trinity and Creation in Karl Barth by Gordon Watson.

- Andrew Sullivan is Thinking Out Loud.

- David Bentley Hart’s bizarre thoughtlessness regarding pacifism by Brian Hamilton. Dave Belcher also posts on David Bentley Hart.

- The New York Times is running some photographs (by Jehad Nga, who was one of American Photo’s Emerging Artists in 2007) and audio of US troops leaving Iraq.

- Protect peaceful Moldovan protesters from police ill-treatment.

- Justine Toh on Clint Eastwood and the ethics of violence.

- And in case you missed it: David’s Ten Theses on Prayer and Ben’s stellar reflection on Led Zeppelin IV.

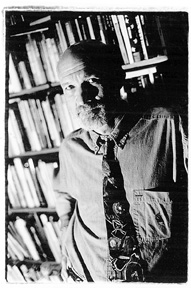

Karl Barth

Towards a theology of the child: a series

Barth on our being in Christ

‘To be a Christian is per definitionem to be in Christ. The place of the community as such, the theatre of their history, the ground on which they stand, the air that they breathe, and therefore the standard of what they do and do not do, is indicated by this expression. Being in Christ is the a priori of all the instruction that Paul gives his churches, all the comfort and exhortation he addresses to them. – Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/2, p. 277.

‘To be a Christian is per definitionem to be in Christ. The place of the community as such, the theatre of their history, the ground on which they stand, the air that they breathe, and therefore the standard of what they do and do not do, is indicated by this expression. Being in Christ is the a priori of all the instruction that Paul gives his churches, all the comfort and exhortation he addresses to them. – Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV/2, p. 277.

Around the traps …

Richard Floyd enters blogdom with a delightful rumination on ‘How Communication Technology has Changed the Scholarly Life‘ and A Hymn for Lent.

Richard Floyd enters blogdom with a delightful rumination on ‘How Communication Technology has Changed the Scholarly Life‘ and A Hymn for Lent.

- Phil Baiden writes an appreciation of PT Forsyth.

- Stanley Hauerwas delivers Carey’s annual Grenz Lectures:

- Lecture One: “Learning the Languages of Peace”.

- Lecture Two: “A Worldly Church: Politics, Theology and the Common Good”.

- Jim Gordon (who normally blogs here) on Seeking God and Benedictine Spirituality

- Peter Singer and John Hare on Moral Mammals – Why do we Matter? – Does theism or atheism provide the best foundation for human worth and morality?

- The latest IJST (11/2) is out, and includes articles on:

- ‘Development of Doctrine, or Denial? Balthasar’s Holy Saturday and Newman’s Essay’ (p 129-145), by Alyssa Pitstick

- ‘The Descent into Hell as a Solution for the Problem of the Fate of Unevangelized Non-Christians: Balthasar’s Hell, the Limbo of the Fathers and Purgatory’ (p 146-171), by Gavin D’Costa

- ‘One Commixture of Light’: Rethinking some Modern Uses and Critiques of Gregory of Nazianzus on the Unity and Equality of the Divine Persons’ (p 172-189), by Ben Fulford

- ‘The Cruciality of the Cross’: P.T. Forsyth’s Understanding of the Atonement’ (p 190-207), by Theng-Huat Leow (Congratulations Theng-Huat!!)

- ‘The Grammar of Pneumatology in Barth and Rahner: A Reconsideration’ (p 208-224), by Travis Ables

Lent Reflection 2

‘To the picture of the free but divinely ordained determination of the existence of Jesus to this outcome there must also be added everything that is said in the Gospels about the world around, in which the “wicked husbandmen” are given particular prominence as the decisive agents. We are not set at an indeterminate point in world history. The passion of the Son of Man is, of course, the work of the Gentiles, of Pilate and his race, but only secondarily and indirectly. Pilate has to be there, In more than one respect, especially as the responsible (although not really responsible) representative of government, he is one of the central figures in the Gospel story. Unwillingly and unwittingly he is the executor Novi Testamenti (Bengel). For by delivering Jesus to him, Israel unwittingly accomplishes-“they know not what they do” (Lk. 23:34)-His handing over to humanity outside Israel, and the Messiah of Israel becomes the Saviour of the world. Again, as Pilate delivers him to his men for execution, he is the man by whose will and work the divine act of redemption is accomplished. It is not the case however, as in some schematic presentations, that Israel and the Gentiles, Church and state, co-operated equally in accusing and condemning Jesus and destroying Him as a criminal. It is not for nothing that the one who initiates this action is the apostle Judas, and in his person the elect tribe of Judah to which Christ Himself also belonged, and in Judah (the Jews, as they are summarily described in John) the chosen and called people of Israel. It is in this sphere that we find ourselves in the passion story. We are not really in the main theatre of world history, but in the vineyard of the Lord. It is Israel, represented by its spiritual and ecclesiastical and theological leaders, but also by its vox populi, that refuses and rejects and condemns Jesus and finally delivers Him up as a blasphemer to the Gentiles, to be executed by them as a political criminal, although Pilate is quite unable and unwilling to pronounce Him guilty as such, and only causes Him to be put to death unjustly and against His better judgment. It was to this delivering up by this Israel which rejected and condemned Him, to death at the hands of this people, to this conclusion of His history that Jesus gave up Himself, and was given up by God. This is what we must always keep before us in our understanding of His passion’. – Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV.2 (ed. G.W. Bromiley and T.F. Torrance; trans. G.W. Bromiley; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1958), 260.

‘To the picture of the free but divinely ordained determination of the existence of Jesus to this outcome there must also be added everything that is said in the Gospels about the world around, in which the “wicked husbandmen” are given particular prominence as the decisive agents. We are not set at an indeterminate point in world history. The passion of the Son of Man is, of course, the work of the Gentiles, of Pilate and his race, but only secondarily and indirectly. Pilate has to be there, In more than one respect, especially as the responsible (although not really responsible) representative of government, he is one of the central figures in the Gospel story. Unwillingly and unwittingly he is the executor Novi Testamenti (Bengel). For by delivering Jesus to him, Israel unwittingly accomplishes-“they know not what they do” (Lk. 23:34)-His handing over to humanity outside Israel, and the Messiah of Israel becomes the Saviour of the world. Again, as Pilate delivers him to his men for execution, he is the man by whose will and work the divine act of redemption is accomplished. It is not the case however, as in some schematic presentations, that Israel and the Gentiles, Church and state, co-operated equally in accusing and condemning Jesus and destroying Him as a criminal. It is not for nothing that the one who initiates this action is the apostle Judas, and in his person the elect tribe of Judah to which Christ Himself also belonged, and in Judah (the Jews, as they are summarily described in John) the chosen and called people of Israel. It is in this sphere that we find ourselves in the passion story. We are not really in the main theatre of world history, but in the vineyard of the Lord. It is Israel, represented by its spiritual and ecclesiastical and theological leaders, but also by its vox populi, that refuses and rejects and condemns Jesus and finally delivers Him up as a blasphemer to the Gentiles, to be executed by them as a political criminal, although Pilate is quite unable and unwilling to pronounce Him guilty as such, and only causes Him to be put to death unjustly and against His better judgment. It was to this delivering up by this Israel which rejected and condemned Him, to death at the hands of this people, to this conclusion of His history that Jesus gave up Himself, and was given up by God. This is what we must always keep before us in our understanding of His passion’. – Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics IV.2 (ed. G.W. Bromiley and T.F. Torrance; trans. G.W. Bromiley; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1958), 260.

Karl Barth on Children

According to Hans Frei, what distinguished Karl Barth (1886-1968) as a theologian was the ‘startlingly consistent’ identification of ‘universal divine action with divine action in Christ alone’.[1] ‘Here God is present and known to us, and the only logical presupposition for this presence and this knowledge is – itself. For this unique thing there can be no set preconditions; it creates it own. No natural theology, no anthropology, no characterization of the human condition, no ideology or world view can set the conditions for theology or knowledge of God’,[2] and, by implication (after Calvin), for knowledge of creation.

This is where Barth begins. Indeed, there can be, for Barth, no other starting point than the eternal decision of God to be God for us – that God, in Jesus Christ elects to be humanity’s covenant partner and redeemer. We cannot understand humanity apart from this eternal decision of God to become incarnate for our sakes. We cannot understand personhood apart from the sovereign God’s decision to make covenant with God’s ‘other’.

While Barth wrote little directly regarding children,[3] Eberhard Busch has observed Barth’s great love for children, and his commitment to them, even when work pulled him away from home, and from his wife Nelly who assumed the major role in bringing up the Barth children. Busch records that around the time Barth was finishing writing the second edition of Der Römerbrief, Barth ‘watched his children … growing up, with care and delight. He still had time, for example, to comb his son Christoph’s hair every morning, “more for my own pleasure than for his gain and satisfaction”‘.[4] Busch also reports how Barth, during his years as pastor in Safenwil (1911-21), immersed himself in his confirmation and pre-confirmation classes, ‘told Bible stories to the twelve- to fourteen-year-olds in the so-called “children’s class” on Sunday after a sermon’, and held weekly meetings for young people already confirmed. He also had strong ideas about the form that these meetings should take: ‘It cannot merely be teaching and learning: we must discover each other personally and become good friends’. He also confessed that these weekly meetings ‘were always a dreadful worry for me’, that he often stood ‘awkwardly in front of bored faces’, and that he usually ‘simply ran out of steam, even in the most well-known things’.[5]

On comparing Augustine with Barth on children, consider these words from Augustine:

Who can recall to me the sin I did in my infancy? For in thy sight no one is clean of sin, not even the infant whose life is but one day upon earth … What, then, was my sin? Was it that I cried for more as I hung upon the breast? … Even in my infancy, therefore, I was doing something that deserved blame, but because I could not understand anyone who blamed me, custom and reason did not allow me to be blamed … It is clear, indeed, that infants are harmless because of physical weakness, not because of any innocence of mind.[6]

Augustine believes that all of us are born with evil tendencies by virtue of original sin. Indeed, he somewhat ‘fused biological ideas of heredity with the idea of the juridical liability of humanity’.[7] This view constitutes the mainstream Christian tradition.

Barth rejects this (negative) view, stressing instead that children are bearers of God’s gracious promise to make them – and indeed all humanity – his covenant partners in Jesus Christ.

Barth also presents three interrelated thoughts about children:

1. Children are needy beginners. They are ‘inept, inexperienced, unskilled, and immature’, but as such they may humbly acknowledge their need and assume a ‘sheer readiness to learn’.[8] Barth, like Calvin, makes a lot of the correlation between children and the life of filial reality before God:

In invocation of God the Father everything depends on whether or not it is done in sheer need (not self-won competence), in sheer readiness to learn (not schooled erudition), and in sheer helplessness (not the application of a technique of self-help). This can be the work only of very weak and very little and very poor children, of those who in their littleness, weakness, and poverty can only get up and run with empty hands to their Father, appealing to him. Nor should we forget to add that it can only be the work only of naughty children of God who have wilfully run away again from their Father’s house, found themselves among swine in the far country, turned their thoughts back home, and then – if they could – returned to their Father … Christians who regard themselves as big and strong and rich and even dear and good children of God, Christian who refuse to sit with their Master at the table of publicans and sinners, are not Christians at all, have still to become so, and need not be surprised if heaven is gray above them and their calling upon God sounds hollow and finds no hearing. The glory, splendour, truth, and power of divine sonship, and of the freedom to invoke God as Father, and therefore the use of this freedom – the Christian ethos in big and little things alike – depends at every time and in every situation on whether or not Christians come before God as beginners, as people who cannot make anything very imposing out of their faith in Jesus Christ, who even with this faith of theirs – and how else could it be if it is faith in Jesus Christ? – venture to draw near to his presence only with the prayer: “Help my unbelief” (Mk. 9:24). Mark well that this has nothing to do with Christian defeatism. It describes Christians on their best side and not their worst, in their strength and not their weakness (2 Cor. 12:10).[9]

That children are ‘beginners’ does not mean that they should be kept in dependence upon their elders. Rather, it implies that they may mature before the covenant God with a spirit of courage and cheerfulness.

2. Being a child is characteristically to be at play. Here Barth draws upon Mozart, whose playing reflects the sheer absence of self-preoccupation. Mozart is not focused on personal confession (as is Beethoven); nor is he about ‘business’ or communicating doctrine (as Barth reads Bach as doing). Mozart just ‘sounds and sings’ with an objectivity that includes ‘an intuitive, childlike awareness of the essence or center – as also the beginning and end – of all things. It is from this center, from this beginning and end, that I hear Mozart create his music’.[10]

3. Being a child is about the opportunity to realise ‘freedom in limitation’. We respond to God’s call as those under the limitations of creation – space and time – and as those elected by God to particular vocations and places of responsibility. The call by the Word of God means freedom. That that same call comes to creatures means limitations. To be a child is to realise this two-fold truth, and to press in various directions in order to identify the boundary between the two – i.e. to step into freedom. This stepping requires what Barth calls a ‘youthful objectivity’.

Youth is the capacity and will to devote oneself to an object without considering or intending that the manner of this devotion should be specifically youthful, but rather in suppression of any such consideration or intention and with the serious aim of rivaling the objectivity of those who are older. He who wants to be a child is not a child; he is merely childish. He who is a child does not want to be a child; he takes his play, his study, his first attempts at accomplishment, his first wrestlings with his environment, in bitter earnest, as though he were already an adult. In so doing he is genuinely childlike. This is what it means to accept the command of the particular hour in true loyalty to its specific determination, to be free in its distinctive limitation.[11]

Directly and indirectly, Barth helps us to ask a number of questions that are pertinent for those in pastoral leadership:[12]

- Do I treat children as gifts who are promised God’s friendship, and not as corrupt or neutral objects who exist for the sake of my control and fashioning?

- Does my care for them communicate hope and possibility rather than a sense of failure and ruin?

- Am I moved to witness good news to other children not my own who need to and by grace may hear it when they have enough to eat, or when they have an opportunity to learn and develop their own powers for responsible life with others?

- And with my own children, do I really place first their relation with God and my summons joyfully to invite them to rejoice with me in God, rather than first insisting that they mimic my life history or ‘make something of themselves’?

Just before his eightieth birthday, Barth sketched a ‘Rule of life for older people in their relationship with the young’. Eberhard Busch recounts Barth’s words:

You must make it clear that our younger relations have the right to go their own way in accordance with their own principles, not yours … In no circumstances should you give them up: rather, you should go along with them cheerfully, allowing them to be free, thinking the best of them and trusting in God, loving them and praying for them, whatever happens.[13]

[1] Hans W. Frei, Theology and Narrative: Selected Essays (ed. George Hunsinger and William C. Placher; New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 228.

[2] Hans W. Frei, Types of Christian Theology (ed. George Hunsinger and William C. Placher; New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1992), 154.

[3] Here I am drawing on an essay by William Werpehowski, ‘Reading Karl Barth on Children’ in The Child in Christian Thought (ed. Marcia JoAnn Bunge; Grand Rapids/Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001), 386-405.

[4] Eberhard Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (trans. John Bowden; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), 121.

[5] Ibid., 64-66.

[6] Augustine, Confessions (trans. Rex Warner; New York: New American Library, 1963), 23-4.

[7] Henry Chadwick, Augustine (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 111.

[8] Karl Barth, The Christian Life: Church Dogmatics IV.4: Lecture Fragments (trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1981), 79, 80.

[9] Ibid., 80.

[10] Karl Barth, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (trans. C.K. Pott; Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2003), 16.

[11] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III.4 (trans. A.T. Mackay, et al.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1961), 609.

[12] These questions are adapted from Werpehowski, ‘Barth on Children’, 405.

[13] Busch, Karl Barth, 476.

Friedrich Schleiermacher on Children

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (1768-1834) is among the most significant Reformed theologians between Calvin and Barth.[1] What constitutes an area of great neglect in his thought, however, is his thinking on children, explored in a number of his writings: Soliloquies (1800), Celebration of Christmas (1806) and Sermons on the Christian Household (1820). He was concerned throughout to explore a number of questions:

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (1768-1834) is among the most significant Reformed theologians between Calvin and Barth.[1] What constitutes an area of great neglect in his thought, however, is his thinking on children, explored in a number of his writings: Soliloquies (1800), Celebration of Christmas (1806) and Sermons on the Christian Household (1820). He was concerned throughout to explore a number of questions:

- What is the child?

- What is the unique spiritual perspective of childhood?

- Must maturity alienate us from childhood?

- How might parents best nurture their children and draw out the unique individuality that expresses itself in children?

These kinds of questions were explored against the backdrop of a rise in the importance of the nuclear family as a social institution, and the sharper demarcation between the roll of mothers and fathers – the home, children and emotions were increasingly seen as the domain of mothers, the withdrawal of extended family, etc. More positively, there was greater emphasis on the value of children’s nurture and development through age-appropriate play and education. The period also saw the development of the kindergarten, children’s literature and children’s toys.

More than most theologians, it was Schleiermacher (and later people like Karl Rahner) who believed that children could teach adults, that children – as children – were full human beings and so worthy of respect and dignity. So, in Schleiermacher’s novella The Celebration of Christmas: A Conversation, one of the characters, Agnes, poses a series of important questions:

Is it then the case that the first childish objects of enjoyment must, in fact, be lost that the higher may be gained? May there not be a way of obtaining the latter without letting the former go? Does life then begin with a pure illusion in which there is no truth at all, and nothing enduring? How am I rightly to comprehend this? In the case of the man who has come to reflect upon himself and the world, and who has found God, seeing that this process is not gone through without conflict and warfare, do his joys rest upon the eradication, not merely of what is evil, but of what is blameless? For it is thus we always indicate the childlike, or even the childish, if you will rather so have it.[2]

In 1834, Schleiermacher preached a sermon on Mark 1:13-16. In exegeting v. 15 [‘anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it’], he noted:

The peculiar essence of the child is that he is altogether in the moment … The past disappears for him, and of the future he knows nothing – each moment exists only for itself, and this accounts for the blessedness of a soul content in innocence.[3]

This, Schleiermacher believes, is a child’s gift to adults, and it is towards a recovery of precisely this perspective that Jesus has in mind for those who would enter the Kingdom of God – that those who know communion with God might live in the present with no anxiety about past or future. So DeVries on Schleiermacher:

Children remind us of the fact that God created humanity to live simply. They help adults shed their obsession with the complexities of work and public life. Indeed, children draw adults back into the most basic of human relationships.[4]

Celebration of Christmas is a revelation into Schleiermacher’s theology (on many levels) and not least his (overly)-optimistic view of human personhood. It was this that Barth, in his 1923/24 Göttingen lectures on the Theology of Schleiermacher, rightly picked up on, criticising Schleiermacher for positing an anthropology too without regard for an adequate account of the realities of sin, conversion and the in-breaking of the Word of God.

In those lectures, Barth’s reading of Schleiermacher’s ‘Christological Festival Sermons’ (as Barth calls them) spans some 50 pages wherein Barth expresses his usual mixture of appreciation and criticism for the Silesian-born theologian. One place where Barth’s praise for Schleiermacher’s Christmas sermons is noted concerns Schleiermacher’s sermon on Acts 17:30-31 [‘In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent. For he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice by the man he has appointed. He has given proof of this to everyone by raising him from the dead’]. On this, ‘the most powerful and impressive Christmas sermon that Schleiermacher preached’, Barth comments:

Let us look beyond the narrow sphere of individual life, Schleiermacher asks in the introduction, to the large and universal sphere. It is the Savior of the world whose coming we celebrate. A new world has dawned since the Word became flesh. His appearing was the great turning-point in the whole history of the human race. What is the change whereby the old age and the new may be distinguished? The fact that ignorance of God is no longer overlooked and tolerated by God. Christ’s life was from beginning to end an increasing revelation. The world’s childhood ended with it. Sin is now known and the image of God is evident. Hence judgement passes on all human action, and we ought to rejoice at this. We are now told that he commands everyone everywhere to repent.[5]

DeVries suggests that Barth’s reading of Schleiermacher’s (positive) child-anthropology is not nearly as nuanced as it ought to be. She notes that, for Schleiermacher, children a not perfect and sinless mediators of the higher life and are born with as much potential for sin as for salvation, and that it is the parents’ duty to nurture their children’s ‘higher self-consciousness’ which connect them to the transcendent and also opens their hearts to others.[6]

Rather than follow the formal catechesis that Calvin and Luther had stressed (and which Schleiermacher thought were too impersonal), the Moravian/Pietist-educated Schleiermacher stressed that the Christian home is the ‘first and irreplaceable school of faith’, for only here can children really experience the full range of what Christian faith is about and so come to faith in Christ. Schleiermacher believes that faith is more ‘caught’ than ‘taught’.

Still, he notes that parents can also damage a child in a number of ways:

- by failing to take their concerns/interests seriously.

- by failing to respond empathetically or appropriately to their emotions.

- parents whose own emotional lives are chaotic or unreliable will drive their children into secrecy.

- by attempting to live their own dreams/aspirations through children.

Schleiermacher also stresses that pastors have a pivotal role to play in children’s faith, among the most important duty of which is informal and personalised catechises where the focus is on leading children to develop, in DeVries words, ‘sound and sophisticated abilities in reading and interpreting scripture. Such instruction might begin with memorizing Bible verses, but it should eventually lead to developing in children a way of thinking (Gedankenerzeugungsprozess) that can be applied to questions or situations that will arise when the catechizing process is over’.[7] In other words it is about helping children to think theologically about all of life. DeVries continues:

Schleiermacher holds high expectations of the catechizing pastor. He states that when children who have been raised in the church lose their faith in adulthood, it is often because they have received poor catechetical instruction. Mindless repetition of correct answers will not sustain faith through the journey to adulthood. Pastors should treat children as fellow seekers who will be no more satisfied with pat answers than adults. If there is a virtue to be developed in the teaching pastor, it is the virtue of humility, for teaching the faith is probably his [sic] most difficult task. Schleiermacher urges his ministry students always to consider their teaching a work in progress, and challenges them to be quick to admit their mistakes.

What children need more than anything else is living faith in Christ. Parents, teachers, and pastors must devote all their energy and enthusiasm to presenting Christ to their children. This is best achieved through the whole of life itself, lived with children. They should feel the love of adults as “reflecting the splendour of eternal love” in Christ. Children who have received the Spirit in baptism and who have been raised within the loving discipline of the Christian community give us reason to hope for the future.[8]

[1] Here I draw heavily upon an essay by Dawn DeVries, ‘”Be Converted and Become as Little Children”: Friedrich Schleiermacher on the Religious Significance of Childhood’ in The Child in Christian Thought (ed. Marcia JoAnn Bunge; Grand Rapids/Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001), 329-49.

[2] Friedrich Schleiermacher, Christmas Eve: A Dialogue on the Celebration of Christmas (trans. W. Hastie; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1890), 33.

[3] Friedrich Schleiermacher, Friedrich Schleiermachers sämmtliche Werke (vol. II/6; Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1834-1864), 71-2.

[4] DeVries, ‘Schleiermacher on the Religious Significance of Childhood’, 341.

[5] Karl Barth, The Theology of Schleiermacher: Lectures at Göttingen, Winter Semester of 1923/24 (ed. Dietrich Ritschl; trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley; Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1982), 72.

[6] See DeVries, ‘Schleiermacher on the Religious Significance of Childhood’, 341-2.

[7] Ibid., 345.

[8] Ibid., 346-7.

Around the traps …

- Church and Postmodern Culture has been hosting a great 6-part conversation (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6) on Nathan Kerr’s Christ, History and Apocalyptic: The Politics of Christian Mission. Be sure to also check out Halden’s posts on Kerr’s book too: Mission and Apocalyptic Ecclesiology and The Church as Polis? Some Biblical Reflections

- The latest edition of Journal of Reformed Theology (3/1, 2009) is out and includes articles by Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, Christoph Schwöbel , Robert Letham, Dirkie Smit, Steve Holmes and Seung Goo Lee on the Trinity

- “Where are the Protestants?”

- Registration is now open for the 2009 Karl Barth Conference at Princeton Seminary

- Lots of Barth-related book reviews:

- Christophe Chalamet reviews Stefan Holtmann’s “Karl Barth als Theologe der Neuzeit”

- William Barnett reviews Eberhard Busch’s “Barth”

- David W. Congdon reviews P.H. Brazier’s “Barth and Dostoevsky”

- David W. Congdon also reviews R. Dale Dawson’s “The Resurrection in Karl Barth”

- John L. Drury reviews Stephen Wigley’s “Karl Barth and Hans Urs von Balthasar: A Critical Engagement”

- Shannon Nicole Smythe reviews “A Shorter Commentary on Romans by Karl Barth

- Shannon Nicole Smythe also reviews Donald Wood’s “Barth’s Theology of Interpretation”

- Jason T. Ingalls reviews Matt Jenson’s “The Gravity of Sin: Augustine, Luther, and Barth on Homo Incurvatus in Se”

- Jason T. Ingalls and W. Travis McMaken review Willimon’s “Conversations with Barth on Preaching” and Yocum’s “Ecclesial Mediation in Karl Barth”

- Alexander Massmann reviews Matthias D. Wüthrich’s “Gott und das Nichtige: Zur Rede vom Nichtigen ausgehend von Karl Barths KD § 50”

- W. Travis McMaken reviews Paul T. Nommo’s “Being in Action: The Theological Shape of Barth’s Ethical Vision”

- Shane Wilkins reviews Neil MacDonald’s “Karl Barth and the Strange New World within the Bible: Barth, Wittgenstein and the Metadilemmas of the Enlightenment”

- Byron Smith posts on Dying for the half-hearted and the corrupt

- Peter Liethart asks if there’s not even something right about the vision of Christendom

- Ben Myers posts a great quote from William Cavanaugh on Church and eucharist

- Steve Holmes asks What is evangelism?

- A wonderful excerpt from a new biography on Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Dietrich Bonhoeffer 1906-1945. Martyr, Thinker, Man of Resistance is on its way in October. How awesome is that!

- Unmasking lies about Picasso

- John Pilger on the loss of freedom in totalitarian Britain

- Lawmakers Debate Establishing “Truth Commission” on Bush Admin Torture, Rendition and Domestic Spying: ‘… How did we get to a point where we were holding a legal US resident for more than five years in a military brig without ever bringing charges against him? How did we get to a point where Abu Ghraib happened? How did we get to a point where the United States government tried to make Guantanamo Bay a law-free zone, in order to deny accountability for our actions? How did we get to a point where our premier intelligence agency, the CIA, destroyed nearly a hundred videotapes with evidence of how detainees were being interrogated? How did we get to a point where the White House could say, “If we tell you to do it, even if it breaks the law, it’s alright, because we’re above the law”?’

- Italians get together to remember Calvin

Bruce Hamill: ‘Response to Kevin Ward’s Inaugural Lecture’

Rev Dr Kevin Ward’s recent lecture – ‘It may be emerging, but is it church?’ – has sparked a good deal of constructive conversation, a conversation that was kicked off by a brief public response to the lecture by one who had enquired after one of Kevin’s earlier lectures – ‘So where’s the theology in all this? – the Rev Dr Bruce Hamill. Here’s Bruce’s gracious and insightful response to Kevin’s paper:

Rev Dr Kevin Ward’s recent lecture – ‘It may be emerging, but is it church?’ – has sparked a good deal of constructive conversation, a conversation that was kicked off by a brief public response to the lecture by one who had enquired after one of Kevin’s earlier lectures – ‘So where’s the theology in all this? – the Rev Dr Bruce Hamill. Here’s Bruce’s gracious and insightful response to Kevin’s paper:

Introduction

Thanks for the privilege of responding to today very briefly, in just 10 minutes… Kevin, those who know you expect nothing less than a broad-visioned, scholarly, insightful, pastoral, provocative but conciliatory lecture, grounded in your passion for the church and the gospel. You have not disappointed us…

Since I am expected to ask theological questions I will try not to disappoint.

Right Question?

I particularly liked the provocative title… however, as I have thought about the relation between the title and the concluding answer, I reached the conclusion that, for all its provocation this question is not quite right. Not that I want to avoid your question, but perhaps to narrow down the scope of my response…a better question might be: Does this movement within the church (or among the churches) point the way forward for reform of the body of Christ? Does this movement with its 3 foci of (1) alignment with postmodernism (2) relevance (3) incarnationalism have the theological resources for a missional church in our time? Now my suspicion is that your answer to this question would be a nuanced one, but probably, like mine, a ‘no’. Indeed the last half of your paper demonstrates how the emergent church consistently shows a conflict with the classical marks of the church – a strong indicator that its theological principles and direction is fundamentally flawed. In this respect my response is, I suspect in basic agreement with your view (particularly in the latter half of your paper)

Incarnation and Mission

However, if this is the case, then I fear that the framework you inherit from Niebuhr and others in the missiology movement is too close to that used by the emergent church itself, to really expose its flaws. In what remains of my few minutes response I want to indicate some of the tensions within your argument.

To begin with I would note that your adoption of the term incarnation, as an adjective (‘incarnational’) to represent a stance which is neither isolationist nor accomodationist, raises my theological antennae. This appears to me to be a sociologising of the language of theology – of incarnation – which trades on its theological background.

So to a more directly theological question: What is the incarnation? (in just 5 minutes!) And how does it relate to the church’s cultural existence and mission?

David Congdon, a Princeton theologian who has influenced my response to this, says:

‘the incarnation is sui generis, i.e., it is wholly unique and unrepeatable. In short, the incarnation is an event, not an idea that can be applied or a process that can be completed or a reality that can be replicated.’

What I believe lies behind this is the whole doctrine of divine grace emerging from the church’s experience of salvation in the raising of the crucified Jesus. Namely, that the life of Jesus originated unnecessarily (contingently) and freely from God’s transcendent act and being. In the incarnation God’s freedom from us is the basis for God’s freedom for us in the life of Jesus.

In this sense Jesus life represents a break in the fabric of culture and tradition and original sin. It introduces a radical newness from the Word of God. In this sense the church came to talk of him as being born of a virgin and also suggest that the Holy Spirit ‘overshadowed’ even the maternal contribution to Jesus existence. God enters into the physical conditions of human life, adopting, as it were, the human condition, however this is not an accommodation to or adaption to culture, but rather human culture is here accommodated to the Word of God.

In this sense Jesus life represents a break in the fabric of culture and tradition and original sin. It introduces a radical newness from the Word of God. In this sense the church came to talk of him as being born of a virgin and also suggest that the Holy Spirit ‘overshadowed’ even the maternal contribution to Jesus existence. God enters into the physical conditions of human life, adopting, as it were, the human condition, however this is not an accommodation to or adaption to culture, but rather human culture is here accommodated to the Word of God.

So as Congdon argues, the incarnation cannot be a model for us. However, it does transform and con-form our life. As already enfleshed and enculturated, fallen human beings, we are, because of the incarnation and the form and history it took, reculturated (that’s my word) by God.

In Christ we are not made ‘incarnational’, but a given a history that conforms to his history culminating in death and resurrection. It is here that we see the weakness of the link so often made between ‘incarnation’ and ‘adaptation to human culture’. ‘As the Father sent me…’ refers not to his incarnation but to the form of his life culminating in crucifixion and resurrection – a transformative, salvific encounter with culture.

Other Missional Language in Tension

Let me mention some further places where I think the language of the earlier half of your paper leads you closer to the framework of the ’emerging church’ than the latter half of your paper should allow. You suggest that the aim of missional thinking is a ‘culturally indigenous church’. According to my dictionary “indigenous” means: “born in or originating from where it is found”. If however, the church is created by the crucifixion and resurrection of the incarnate Word it may look like its surrounding culture (like Paul sought to in 1 Cor 9 in order to serve those cultures) but it will not originate from where it is found. The cultural processes that we rely on in the creation of the church are not indigenous processes of human meaning-making. They are the processes whereby God “crunches” from the old order, in all its indigenous and alienated diversity and constant change, a new social order. Jesus very definitely did take the human context in all its particularity seriously, seriously enough to get crucified by it (as you point out). Seriously enough to spend most of his time with those who functioned as essentially non-representative of the culture – the culturally marginalised. I contend that to take culture seriously as Jesus did, is not to conform to its agenda.

As you say ‘there are limits to how far the culture can set the agenda and determine the shape’. My contention is that the issue is not the presence of a limit, but how that limit is set (and who determines it). I believe it is not by the balancing of principles, especially if one of those principles is Andrew Walls’ rather cosy ‘the gospel is at home in every culture and every culture is at home in the gospel’. Such a principle, even if balanced by the pilgrim principle which says that ‘the gospel is never fully at home’, makes the cross the exception rather than the culmination of Christ’s life. One cannot serve two masters, Christ and Culture (as Walls’s balancing act suggests). Cultural processes must have their limits set for them by Christ in the formation of his body, or our enlightenment culture becomes the default determiner of this process.

Church is not people who ‘have the gospel’ (like some ideal) and then apply it, enlightenment style, to the world’s forms. They are worldly people being re-formed by Spirit and Word and re-culturated into a new creation and an anticipation of the kingdom.

Barth, Form and Content

Which brings me to Karl Barth’s problem. He says that there is no ‘sacred sociology’, however I feel he needs to be challenged, by those like John Milbank, to understand the need of a theological sociology – a fuller ecclesiology.

Quoting Barth you say, “If then the church has been, and indeed should (the should is your addition) have its forms determined by whatever the current “political, economic and cultural models” of “its situation in world history” are, does that mean that anything goes?” [loaded question!] Barth has no “should”. I suspect he does not see such accomodation as an ecclesiological virtue – just an inevitability. However, I want to go beyond Barth and challenge the easy separation between form and content. Not only is it not true that anything goes (as you also clearly argue), but it is true that the form as well as the content should be subject to Christ and the Spirit (as you hinted at in places in your paper). This claim does not, as many seem to fear, imply that it will be a fixed form, or that to believe this requires identifying the form that Christ gives the church with a human form from the post. On the contrary it simply requires a formative process, by which enculturated people attend to Word and Sacrament, not just in their private spiritualities but also in their social habits and structures. This is in my view what it means to be a Reformed Church – constantly being re-formed socially.

Thanks again for the chance to respond to your stimulating lecture.

Kevin Ward: ‘It may be emerging, but is it church?’

A week or so ago, I posted some reflections on the emerging church. I offered these in anticipation of Rev Dr Kevin Ward‘s then forthcoming inaugural lecture at the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership entitled ‘It may be emerging, but is it church?’ Kevin delivered his lecture on Monday, which was followed by a brief response by Rev Dr Bruce Hamill. Bruce’s response can be read here. Here’s Kevin’s paper:

A week or so ago, I posted some reflections on the emerging church. I offered these in anticipation of Rev Dr Kevin Ward‘s then forthcoming inaugural lecture at the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership entitled ‘It may be emerging, but is it church?’ Kevin delivered his lecture on Monday, which was followed by a brief response by Rev Dr Bruce Hamill. Bruce’s response can be read here. Here’s Kevin’s paper:

‘IT MIGHT BE EMERGING: BUT IS IT CHURCH?’, a guest post by Kevin Ward

At a recent theological conference I was attending, one of the presenters outlining some of the factors in the changing context for theological education, referred to “fresh expressions” which he said was a more appropriate term than the previously favoured descriptor for experimental faith communities, “emerging church”, since as it turned out most of what they were emerging from was not church. He was Anglican and the term “fresh expressions” is a phrase developed by the C of E for some of its new developments, but the term “emerging church’ is still widespread and gains much attention from younger church leaders in NZ, including many of those accepted for ministry training by the PCANZ and coming to the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership. One of our courses here is now titled “Missional and Emerging Churches.” At the VisionNZ Conference last year one of the major presentations was “A Kiwi Emerging Kiwi Church: Yeah Right!” by Steve Taylor, who has emerged as the leading spokesperson for emerging church in NZ, and a significant global voice. Indeed it is interesting in reading on the movement globally how much NZ comes up in the material as being, along with, Australia and the UK initiators in it. Mike Riddel and Mark Pierson from NZ, and Michael Frost and Alan Hirsch from Australia are seen as pioneers. I might add that as well as being from down under, they along with Taylor are Baptists, a heritage of course I share myself, and something I will come back to.

A google search of “emerging church” came up with about 1,530,000 entries. So what are we to make of what Scot McKnight calls “the most controversial and misunderstood movement in the church today”. One article I read was titled “Emerging Churches – Heroes or Heretics.” Clearly unambivalent about the answer a brochure I received at the beginning of the year blazed out. “The last days Apostacy. Coming to a church near you. The emergent church.” It warns that “With the move of the Church back to Rome through organisations like evangelicals and Catholics together, Alpha, Promise Keepers and Interfaith dialogue… Rick Warren’s Purpose Driven and now the postmodern Emergent wave… believe that today’s post modern culture needs a more relevant and experiential approach to God, Church and Worship. Eg. Playing u2 as an expression of worship using multi-sensory stimulation, candles, icons, art, images, stained glass etc.” And it warns “The Emergent Church has taken hold in NZ and its teachings have been aired on Radio Rhema and also being taught in the BCNZ.” I must point out that the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership you’ll be pleased to know was not listed among those who have fallen into “the last days deception.”

We need of course to ask the question why has this movement arisen? The broad answer is fairly simple: it is part of a number of responses over the past half century to the increasingly obvious fact that the church in particular and Christian faith in general has been having a rather difficult time of it in western societies like NZ. I have written in a number of places on this, as have many others, and have no intention of rehearsing that fact. It is simply a given, whatever figures one uses and however positive the spin one tries to put on them. There have been many responses to this post Christian, or perhaps more correctly post Christendom reality, from the God is Dead theologies of the 60s, through the Church Growth movement of the 70s and Cell Churches of the 80s, to the Seeker Sensitive Churches of the 90s. Despite all these grand initiatives the rot continues.

What emerged in the 1990s was the realisation among some that not only were our western societies post Christendom, but they were also postmodern in at least some ways. That term is rather problematic, and again it is not my intention to explore all the issues around it. However in the broadest sense it is helpful to identify the fact that the cultural, social and intellectual world we live in today is very different from that which existed in 1960, even if there may well be more continuities than discontinuities. In this world all sorts of institutions that have existed for centuries have increasingly struggled. A number of Christian thinkers and leaders began arguing that the problem with all the recent efforts to reorganise church for our postChristendom world, was that they were still based on the assumptions and thinking of a modern society and culture. As that was rapidly diminishing and being replaced by postmodern forms so these attempts were simply short term arrangements, much like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. Something more fundamental was needed.

There are many attempts, some helpful others not, to define the emerging church movement, but perhaps the simplest and most widely used is that by Eddie Gibbs and Ryan Bolger, in their study of the phenomenon, which they titled Emerging Churches¸ “communities that practice the way of Jesus within postmodern cultures.” Brian McLaren, who has emerged as its main spokesperson wrote in 1998 in the first of his many books:

You see, if we have a new world, we will need a new church. We don’t need a new religion per se, but a new framework for out theology. Not a new Spirit, but a new spirituality. Not a new Christ, but a new kind of Christian. Not a new denomination, but a new kind of church… The point is … you have a new world.

Now I want to say at this point that overall I would agree with the broad parameters of this argument. As Randall Prior summarised it at the Presbyterian General Assembly last year, “The form of the church which evolved in the era of Christendom and which served us well in that period is no longer sustainable. It is dying. It will die.” However I do want to add at least one cautionary note. Often the people involved use rather hyperbolic language, as if the church has only ever existed in one form or shape, at least since the inception of Christendom, often referred to as inherited church. Now that old form needs to be discarded and a brand new form developed. This is of course quite misleading. The form and shape of the church has constantly changed throughout its 2000 years of history. We see this even in the NT, and writers such as Hans Kung, David Bosch and Andrew Walls have provided helpful ways of understanding this.

Andrew Walls invites us to imagine a long living, scholarly visitor from space, a Professor of Comparative Inter Planetary Religions, able to get periodic study grants to visit planet earth every few centuries, to study earth religion, Christianity, on principles of Baconian induction. He visits a group of Jerusalem Jewish Christians about 37 CE; his next visit is in about 325 CE to a Church Council in Nicea; then in about 650 CE he visits a group of monks on a rocky outcrop in Ireland; in the 1840s he visits a Christian assembly in Exeter Hall London promoting mission to Africa; finally in 1980 he visits Lagos Nigeria where a white robed group is dancing and chanting through the streets on the way to church. At first glance they might appear to have nothing in common, or be part of the same religious community at all, but on deeper analysis he finds an essential continuity about the significance of Jesus, the use of scriptures, of bread and wine and water. But writes Walls, he recognises that these continuities are “cloaked with such heavy veils belonging to their environment that Christians of different times and places must often be unrecognizable to others, or even to themselves, as manifestations of a single phenomenon.”

At the heart of this debate about these emerging new forms of church life is the question of just what is the relationship between the historic faith and the environment in which it presently finds itself, between Christ and culture, of theology to context . This question is actually at the heart of many of the disputes that go on in the church, and I am aware were fought with some intensity and lasting consequences around a variety of issues in these hallowed halls for some considerable time.

When it comes to the relationship between the church and the culture that surrounds it there are a number of different models used to explain the various orientations. The classic work, which has formed the basis for all following discussions, is that of Richard Niebuhr, in Christ and Culture. He identifies five basic models: Christ against culture, the Christ of culture, Christ above culture, Christ and culture in paradox and Christ the transformer of culture. It seems, though, that the alternatives can be more simply discussed by reducing these to three.

(i) An “anticultural” response, “Christ against culture”. The attitude where the church sets itself up in opposition to the prevailing culture. The difficulty with this position is that there is no such thing as a culture free articulation of theology or understanding of the church. Consequently this position while opposing contemporary culture is in fact usually holding on to some culture of the past. The Amish, for example, hold on to the culture of early nineteenth century German settlers in Pennsylvania, traditional Anglicans to 1950s England and many fundamentalists to the pre 1960s American south.

(ii) An “accommodationist” response, “Christ of culture”. This is the opposite, where the church is so anxious to fit into the world that it becomes merely an extension of the culture and has lost any distinguishing particularity as a culture of its own. This response assumes the congruence of church and culture. It is assumed that the primary symbols of the church and of the culture are identical. The church sees itself in some way as representative of the culture at large and prides itself on its shaping, transforming role. Churches in nations where the two grew up together often exhibit the most radical forms of this. This has been a strong tendency in liberalism in western countries and can be seen as a major factor in the decline of mainstream denominations. The view fails to recognise that there is a basic incompatibility between the church and whatever time in which it lives.

(iii) An “incarnational” response. This response recognises some kind of tension between Christ and culture, as is found in all of Niebuhr’s final three categories. There is both continuity and discontinuity. Lesslie Newbigin rightly insists that the gospel only retains “its proper strangeness, its power to question us… when we are faithful to its universal suprarational, supranational, supracultural nature.” Yet the gospel travels through time not in some ideal form, but from one inculturated form to another. Consequently what missiologists call the “culturally indigenous church” is the aim of the incarnational approach.

A number of different terms are used to describe this approach to culture. The one that I find most helpful is “contextualisation”, although heated debate over its precise meaning continues, with Ecumenical and Evangelical interpretations differing considerably. At the core though is a recognition that many aspects of what humans believe, think, and do are contextually shaped. William Reiser defines it as “the process of a deep, sympathetic adaptation to, and appropriation of, a local culture in which the Church finds itself, in a way that does not compromise its faith.”

At the heart of the process is the model of the incarnation. In Jesus God took the human context in all its particularity seriously. Jesus was a historical person and so he was chronologically, geographically, religiously and culturally a first-century Jew. He neither repudiated his humanity or his Jewishness. The early church continued the principle as the gospel moved out of the language and culture of Jesus and his disciples into that of Graeco-Roman culture. Ever since those most effective in mission have “assumed that any culture can be host to Jesus Christ.”

However the critical point to note in an authentic contextual or incarnational approach is that there are limits to how far culture can set the agenda or determine the shape. Andrew Walls reminds us there are two important principles. On the one hand there is the ‘indigenzing’ principle, which affirms that the gospel is at home in every culture and every culture is at home with the gospel. But then there is the ‘pilgrim’ principle, which warns us that the gospel is never fully at home in any culture and will put us out of step with every society.

So there are two critical dimensions, which Max Stackhouse defines as the “textuality’ of the church – its faithfulness to the gospel – and its “contextuality” – its faithfulness to the world in which it finds itself. Hans Kung contends that we should aim for a “critical correlation” between the biblical message and the paradigm of the culture” and that “the task today is to come to terms with a postmodern paradigm”. The emerging church movement is endeavouring to take that task seriously and is to be commended for that.

If I can engage in a bit of personal narrative at this point, because, in a sense this lecture is part of an ongoing and unfinished conversation with myself. This is the second time I have given the inaugural lecture here. My earlier title was “Is New Zealand’s Future Churchless?” I outlined the paradox of countries like NZ where the data showed an ongoing resilience of relatively high levels of religious, and mainly Christian, believing and relatively low and declining levels of religious belonging. In light of this while it seemed religion was destined to continue rather than die out, as had been previously postulated in various forms of secularisation theory, the church itself may face a somewhat tenuous and uncertain future. I suggested that it would continue but needed to develop many more diverse forms, and these in essence would be “less church” in the sense of being much looser, less institutionalised, more eclectic, fluid rather than solid. Sounds much like emerging church!

After the address, Bruce Hammil, who through fate or destiny has been asked to be the respondent today, came up to me and asked “Where’s the theology in all of this?” A somewhat surprising question from Bruce! It was though a healthy rejoinder to me and a reminder that, central to my own thesis was the proposition that churches which had thrived had not only shown an ability to adapt their life and message to their rapidly changing cultural and social situation, but had also held a strong commitment to the central tenets of orthodox Christian belief. My major focus has been on the first half of that proposition, endeavouring to help churches realise the forms their life and message have taken have been wedded to a cultural and social context that has not existed for some time, and while they continue in their current form they indeed have a rather limited future. They are no longer incarnating the gospel in their context. To quote the new leader of the Labour Party, they have “lost touch with their electorate” and “need to reconnect”. Change is the essential challenge for the church, and I continue to be invited to help a broad range of churches understand the context they are in and how they might change to become culturally connected.

Now this is an essential task. While in some realms of theology we might be able to argue for some pure theology of the word, although I am somewhat sceptical of both the possibility and worth of that, even that great theologian Karl Barth, so often used to buttress the case for disregarding context when it comes to constructing theology, that it must be based solely on the self revelation of God in Christ, argued when it came to the church:

… in every age and place its constitution and order have been broadly determined and conditioned by political, economic, and cultural models more or less imperatively forced on it by its situation in world history… It has had and still has to adapt or approximate itself to these in order to maintain itself… in respect of the form of its existence… there is no sacred sociology [of the church].

There are then no sacred forms of church, however sacrosant these might appear to some. Of course we in the reformed tradition have always held this to be so, holding central to our understanding the reformation principle, ecclesia reformata semper reformanda. If then the church has its forms determined by whatever the current “political, economic and cultural models” of “its situation in world history” are does that mean that anything goes? That the answer to Bruce’s question is that “theology does not have a place in determining the form of church life.” That in fact ecclesiology is a pointless discipline. There is not a theology of the church, merely a praxis.

It is interesting to review literature on the church, from a historical perspective. It used to be for centuries that the basic questions these endeavoured to answer was “What are the marks of a true church?” From the 1970s on the nature of the question most writing was endeavouring to answer had changed, by one word. Instead of “What are the marks of a true church?” it was “What are the marks of a successful church?” – the word ‘successful’ some times being interchanged with the word ‘growing’, since to be successful was equated with growing. Probably two things lay behind this: as the decline of churches in the west became increasingly evident the overwhelming preoccupation became with turning decline into growth; and as the church splintered into greater and greater variety as the culture became more and more diverse, it became seen as a hopeless task to try and presume there was any true form. It was reinforced by a developing culture that became suspicious of any insistence on adherence to one particular form or expression in any area of life. Indeed ideology became the enemy, grammar was fascist, theory was irrelevant, praxis was what mattered. I might add that in NZ, which has always had a bent toward pragmatism and suspicion of intellectualism, all of this found fertile ground.

And so in the emerging church movement there is a sense of anything goes. For those for whom tradition or inherited forms are in fact the obstacle to being effective churches and a barrier to the mission of Jesus, it is a waste of time to listen to what it might have to say us about how the church should form its life. Graham Redding may have asked the question did Calvin have any place in the Café Church? in his 2005 inaugural lecture, but café church is relatively mild fare and rather orthodox when church can apparently be a bunch of kids at a skate board park or bmx track, a group of students gathering in pub or dance club, or some mid life couples sharing a few wines and a movie together.

So when is a gathering of followers of Jesus actually a church?

Many of those engaged in experimental forms of church argue that because Jesus promised that “wherever two or three come together in my name, there am I with them”, any such gathering is church. Within the Baptist tradition this is the primary definition that is used, as in the Pentecostal and Charismatic streams. The presence of Jesus by the Spirit is all that matters. It is thus no coincidence that many of the initiators of the emerging church movement in NZ and Australia have been Baptist. Such a simple definition leaves them much freer to experiment with a diversity of forms. I would hasten to add that for some quite some time I would also have held that as sufficient. It is interesting to observe though that the Baptist movement in NZ, after being driven by sheer pragmatism for the past couple of decades, is now acknowledging it has significant problems and challenges. The current leader of the movement in conversation with me in December said “our first task is to get our ecclesiology sorted out”. Interesting for me in that this drift was a significant factor in my leaving to become Presbyterian.

Further reflection though has made me realise I was still more Baptist than I imagined. As I mentioned one half of my thesis argued that effective churches had maintained a strong commitment to the central tenets of orthodox Christian beliefs. I identified these as being beliefs about Jesus Christ, about God, about scripture and about conversion, and used the Nicene Creed to define these. Nothing about the church though. No ecclesiology. And of course the Nicene Creed does include among its statements “We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic church”. So if we use this as a measure how does the emerging movement measure up? Is it in fact church?

1. One. Everybody affirms the unity or the oneness of the church, but ever since the Schism of 1054 that oneness has been somewhat difficult to locate, and since the splintering of the Reformation even more so. Daniel Migliore helpfully defines it as “a distinctive unity rooted in communion with God through Christ in the Spirit. The unity of the church is a fragmentary and provisional participation in the costly love of the triune God.” Recent trinitarian theology with its focus on a plurality within an essential oneness is helpful for us in understanding how the Christian gospel embraces both diversity and unity. Much of the NT is written dealing with this issue. The unity of the church does not lie in either a controlling doctrinal conformity or a formal institutional structure, and I would eschew all endeavours to impose either of those kinds of unity on the church. Within the diversity of our expressions it is in the life we participate in together with the triune God, and as Hans Kung expresses it, “It is one and the same God who gathers the scattered from all places and all ages and makes them into one people of God.”

However ever since the Reformers placed the focus on seeing the unity of the church in the invisible church rather than the visible church, that understanding has been used as a way of enabling churches and their leaders to do nothing about working to see unity as an actual mark of the church in its present reality. We have continued to be happily schismatic, tearing apart the fabric of church it seems whenever we have something on which we differ. What has been called the “creeping congregationalism”, which afflicts all varieties of church life in contemporary societies, heightens the tendency to focus on the local and the particular, as if that is all there was to being church. Jesus left behind a visible community not an invisible concept. A community he called to be one, and so it is incumbent on we who are the church to continually work hard to find ways to express in our increasingly diverse culture that this is a reality, not merely some ethereal and mystical entity. If the life of the trinity is the model of our unity then it does involved the diverse members working synergistically together for the glory of the one. One of my criticisms of the emerging church movement, is that with its brisk dismissal of inherited forms of church life, its distancing itself from tradition, its reluctance to work with the church as it is, it magnifies the image of a divided church and fails to put energy into working hard at ways to give expression to and so maintain the unity of the church. While I would admire its willingness to engage with our cultures and seek to find new ways of incarnating gospel and church within those, I believe it would be more true to being the church of Jesus Christ in the world today if it sought to do that working with the church as it already is. Brian McLaren says we need “a new church”. There is only one church, and it already is. The challenge is to continue to work within that church so it might better faithfully be the presence of God in Christ through the Spirit in the diverse communities it inhabits.

2. Holy. The word holy and the concept of holiness is hardly a popular word in our contemporary context, either inside or outside the church. It raises images of a “holier than thou” judgmentalism and an isolationist separatism fearful of contamination by an evil world. A preoccupation with holiness it is suggested has been a major hindrance to the mission of the church in the world. Identification and engagement with the world is what the creator God is about. The word holy is of course the primary word used to name the essence of the nature of God. It is if you like what marks out God as God, as distinctly different from everything else in creation. It is something that belongs essentially to God. For other things or persons to be described as holy therefore is to claim that they also are marked by the essence of the character of God, and in this way are to some extent different from the rest of creation. But how do we know what God is like if we are to share in that character. The central claim of the NT and of Christian thought is that the fullest revelation of God is to be found in the human person Jesus Christ. By looking at the life of Jesus we see what it is like to live a human life marked by the character, or holiness, of God. But more than that the NT claims that by his death, resurrection and gift of the Holy Spirit Christ mediates to us the very life of God so we can share in the fellowship of the trinity. Here is the essence of the holiness of the church. It can be identified by the degree to which it lives a life reflecting the glory of God seen in Christ and this is made possible by the presence of the Spirit in its midst. When we do this we will demonstrate a distinctive quality to our life that will indeed mark us out as different, distinct from others, as Peter put it a “peculiar people”. While this quality of holiness will be demonstrated in the church in an imperfect way, as Calvin put it, it is the “measure toward which it is daily advancing”.

As suggested in my overview of the relationship of church and culture, the church lives in a relationship of some tension with whatever culture it lives in. It needs to both incarnate the gospel into that culture but also allow the gospel to transcend and judge every culture in which it is present. Part of the problem with Christendom and the way of being church that developed in that context, is that it ended up identifying the culture of those societies as being Christian, and simply became a reflection of the societies in which they existed. They no longer were a distinct or holy people. As the society and the culture in which they existed changed rapidly in the post war era they ended up with nothing left to offer the new societies which emerged and were seen as antiquarian reminders of a world that once was. Dean Inge once said that “If you marry the spirit of the age you will find yourself a widow in the next.” Sadly that has come to be true of much of mainline Protestantism in the West, including many of its evangelical expressions, shaped more by the values of the consumer market and business models than the gospel. The emerging church movement has been quite right in much of the critique it has offered of the way in which traditional church life had been simply an expression of modern western life and values.

As suggested in my overview of the relationship of church and culture, the church lives in a relationship of some tension with whatever culture it lives in. It needs to both incarnate the gospel into that culture but also allow the gospel to transcend and judge every culture in which it is present. Part of the problem with Christendom and the way of being church that developed in that context, is that it ended up identifying the culture of those societies as being Christian, and simply became a reflection of the societies in which they existed. They no longer were a distinct or holy people. As the society and the culture in which they existed changed rapidly in the post war era they ended up with nothing left to offer the new societies which emerged and were seen as antiquarian reminders of a world that once was. Dean Inge once said that “If you marry the spirit of the age you will find yourself a widow in the next.” Sadly that has come to be true of much of mainline Protestantism in the West, including many of its evangelical expressions, shaped more by the values of the consumer market and business models than the gospel. The emerging church movement has been quite right in much of the critique it has offered of the way in which traditional church life had been simply an expression of modern western life and values.

But while some of its analysis of what has been problematic for the church is invaluable, in its headlong rush to become relevant to the emerging culture of a postmodern world, it runs the risk of making the same mistake and may end up wedding itself to the spirit of this age, just as firmly as the church it critiques may have to a previous age. When the wonders of this age begin to wind down, and I might suggest it might be a phase in history that is much more short lived than the previous, where will it be then? What will it have to offer and to say when all its flaws have been laid bare. The emerging church articulates strongly an incarnational theology and understands Jesus almost solely in these terms. Yet any serious reading of the life and ministry of Jesus will identify that while he did live incarnationally within the culture of first century Judaism, he also lived in considerable tension with most in that culture, at times spoke judgement on it, and ended up being rejected by it. If he was simply concerned with relevance why was he strung up on a cross. At times it is difficult to distinguish an emerging café or night club church from any other café or night club down the street. Postmodern culture is neither any better nor any worse than modern culture. So emerging leaders celebrate the death of modernity and raise three cheers for the arrival of postmodernity, without recognising the need to provide a proper critique of that which is problematic for living a Christ shaped life. On the other hand some critics of the emerging movement such as Don Carson and David Wells see only a culture antithetical to Christ in postmoderrnity, and fail to recognise they are just as closely wedded to the culture of modernity. Whatever culture we happen to be in as the church of Jesus Christ, we need first to allow Christ by the Spirit to form us into a distinctive culture of its own that preaches in the language of the time and place in which it is set the unique holy life of our Trinitarian God.

3. Catholic. The affirmation of the catholicity of the church refers to its universality and inclusivity. It is the church that has existed everywhere, always and for all. It guards the church against parochialism, sectarianism, racism and conceit chronology, among other things. It is clear that both the unity and the catholicity of the church go together, they are two interwoven dimensions of the one church. However as with oneness we need to guard against it being understood merely as an abstract kind of universalism hovering over the particularities of culture and history. Again it is a mark that needs to be demonstrated in the life of the visible church, its expression in the life of local congregations. Avery Dulles claims that catholicity “is not the accomplished fact of having many members or a wide geographical distribution, but rather the dynamic catholicity of a love reaching out to all and excluding no one.” I would agree with Daniel Migliore that the “church today needs to interpret the meaning of catholic as inclusive of all kinds of people”. What might this mean for us today?

One of the major trends of a post 60s world of the global village, has been a growing pluralism of our societies. Not just through the coming to societies such as NZ of markedly different cultural groups from overseas, but also by the breakup of the dominant white European culture into a multiplicity of subcultures. Not only is this across generations, but also within generations, so much so that since the beginning of the 90s it has been pointless to talk even about youth culture. This pluralisation has been heightened by the fact that increasingly people do not live their life in one geographical place where they might mix with people of a wide variety of ages and cultures, but rather are mobile and live their life with communities of choice, usually consisting of people of the same culture as me. Often these subgroups are quite exclusive, having their own distinctive language, symbols and lifestyles. At a time in the past when people in a community lived their lives in that particular community, when generations shared many of the activities of life together, the local church embraced within its community members from every walk and stage of life within that community. It was catholic, inclusive, in that sense. This was the parish or family church, an increasingly rare bird in our pluralistic society. How do we reach people today within all these different cultural subgroups, when the culture of church as it is, represents that culture of a bygone age?

The answer of much of the emerging church is that we need separate churches to incarnate the gospel into all those cultural subgroups. And so we have youth church, student church, young adults church, young marrieds church, breakfast church, café church, biker church – and so on and so on. These churches become quite age or culture specific. One practical question to ponder is what happens to these churches when their particular niche finishes? But there is a bigger issue. Murray Robertson retires this month after 40 years as Pastor of Spreydon Baptist Church during which he has had significant influence on the church in NZ. Last year he served as President of the Baptist Church, and wrote a series of columns in the Baptist Magazine on his observations as he visited churches around NZ. In one of these he noted that churches now “tend to divide along shared interest lines” and there is “an age based apartheid”. He writes “Maybe this is part of the phenomenon of people looking for a church in which they will feel comfortable, but… something quite precious is lost when you only meet and share with people who are pretty much identical to yourself.” Indeed is it a church when its membership is so exclusively limited to some subgroup that others are in fact shut out? The emerging church movement is again to be commended for its recognition that in our multicultural world there is no one expression of the gospel that will incarnate it for “all” those, even within one community in NZ. They draw correctly on the missional principle Paul spells out in 1 Corinthians 9 of becoming “all things to all peoples so that I might by all possible means save some”. But that needs to be balanced by the ecclesial principle he spells out in Ephesians 2, talking about the major cultural divide of his world, that “Christ…. Has made the two one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall… to create in himself one new humanity.” Maybe what is a legitimate mission group is not in fact a church. It needs to see itself as part of the church catholic, and commit itself to being part of that church, and share its life with the greater whole in its lived practices, so that in this fractured divided tribalised world people may see that the gospel makes a difference, that estranged groups can be reconciled, that in Christ cultural separation might be transcended and that the new community of God’s people is inclusive of people of every race and every tribe and every tongue, even here now on earth. Might these questions also be asked of ethnic specific churches? To quote David Bosch