The scene is the office of the dean of admissions at Instant College. A pale adolescent approaches the dean, who is appropriately clad in flowing white memos.

The scene is the office of the dean of admissions at Instant College. A pale adolescent approaches the dean, who is appropriately clad in flowing white memos.

STUDENT: Y-you sent for me, sir?

DEAN: Yes, my boy. We’ve decided to accept you as a student here at Instant.

STUDENT: Sir, I can’t tell you how pleased I am. I mean, my high school average is 65, I got straight Ds in mathematics, confuse the Norman Conquest with Dday, have a sub-average IQ, and got turned down by every other college in America. Yet in spite of all of this, you’ve accepted me.

DEAN: Not in spite of it, boy! Because of it!

STUDENT (dimly): Sir?

DEAN: Don’t you see? You’re a challenge. We’re starting with nothing—you. Yet before we’re through, corporations will seek your advice, little magazines will print your monographs on such arcane subjects as forensic medicine and epistemology, newspapers will publish your utterances as you enplane for conferences abroad.

STUDENT: Me?

DEAN: You. Because you will be an Expert.

STUDENT: An expert what?

DEAN: Just an Expert.

STUDENT: But sir, I don’t know anything and I can’t learn much. Not in four years, anyway.

DEAN: Why, my boy, we’ll have you out of here in an hour. All you need is the catalyst that instantly transforms the lowest common denominator, you, into an Expert.

STUDENT: Money? Power? Intellect? Charm?

DEAN: No. These things are but children’s toys compared to Jargon.

STUDENT: Jargon?

DEAN (turning to his textbook): The dictionary calls it “confused, unintelligible language: gibberish, a dialect regarded as barbarous or outlandish.” But we at Instant call it the Expert’s Ultimate Weapon. In 1967, it will hypnotize friends, quash enemies and intimidate whole nations. Follow me.

A school bell rings, and the entire faculty enters: Dr. Gummidge, professor of sociology; the Rev. Mr. Logos, head of the theological seminary; Dr. Beazle, head of the medical school; Mr. Flap, instructor in government; and finally, General Redstone, chief of the ROTC. Dr. Gummidge steps forward, conducts the student to an uncomfortable chair, mills about him like a lonely crowd, and begins.

GUMMIDGE: Remember Gummidge’s Law and you will never be Found Out: The amount of expertise varies in inverse proportion to the number of statements understood by the General Public.

STUDENT: In other words?

GUMMIDGE: In other words, never say “In other words.” That will force you to clarify your statements. Keep all pronunciamentos orotund and hazy. Suppose your mother comes to school and asks how you are doing. Do I reply: “He is at the bottom of his class—lazy and good-for-nothing”?

STUDENT: Why not? Everyone else does.

GUMMIDGE: I am not everyone else. I reply: “The student in question is performing minimally for his peer group and is an emerging underachiever.”

STUDENT: Wow!

GUMMIDGE: Exactly. If you are poor, I refer to you as disadvantaged; if you live in a slum, you are in a culturally deprived environment.

STUDENT: If I want to get out of a crowded class?

GUMMIDGE: You seek a more favorable pupil-teacher ratio, plus a decentralized learning center in the multiversity.

STUDENT: If I’m learning a language by conversing in it?

GUMMIDGE: That’s the aural-oral method. Say it aloud.

The student does and is completely incomprehensible. A cheer goes up from the faculty.

GUMMIDGE: From now on, you must never speak; you must verbalize.

STUDENT: Must I verbalize Jargon only to my peer group?

GUMMIDGE: Not at all. You can now use it even when addressing preschoolers. In his book Translations from the English, Robert Paul Smith offers these samples: “He shows a real ability in plastic conception.” That means he can make a snake out of clay. “He’s rather slow in group integration and reacts negatively to aggressive stimulus.” He cries easily. And “He does seem to have developed late in large-muscle control.” He falls on his head frequently.

STUDENT (awestruck): I’ll never be able to do it.

GUMMIDGE: Of course you will. The uninitiated are easily impressed. It’s all rather like the ignorant woman who learns that her friend’s son has graduated from medical school. “How’s your boy?” she asks. The friend clucks sadly: “He’s a practicing homosexual.” “Wonderful!” cries the first. “Where’s his office?” Do I make myself clear?

STUDENT: No, sir,

GUMMIDGE: Fine. Now open your textbook to the David Riesman chapter. Here is the eminent sociologist writing about Jargon: “Phrases such as ‘achievement-oriented’ or ‘need-achievement’ were, if I am not mistaken, invented by colleagues and friends of mine, Harry Murray and David C. McClelland … It has occurred to me that they may be driven by a kind of asceticism precisely because they are poetic men of feeling who . . . have chosen to deal with soft data in a hard way.” Now then, my boy, is there any better example of flapdoodle than that?

STUDENT: Well, how about these samples from Harvard Sociologist Talcott Parsons: “Adaptation, goal-attainment, integration and pattern maintenance.”

GUMMIDGE: Yes, first rate. Even I practice them, just as Horowitz plays the scales. Try them in a sentence. Two men open a store. Someone provides the cash. What’s that?

STUDENT: Adaptation?

GUMMIDGE: And then they entice customers—

STUDENT: Goal-attainment.

GUMMIDGE: They set up a sales staff—

STUDENT: Integration.

GUMMIDGE: And they don’t steal from the cash register.

STUDENT: They agree to maintain the wider values of the culture. That’s pattern maintenance.

GUMMIDGE: Perfect. See how complicated you can make things? Imagine what damage you can wreak in the schools where a situation is no longer practical, it is viable; where a pupil is no longer unmanageable, but alienated. Get it?

STUDENT: Got it.

GUMMIDGE: Do books have words and pictures?

STUDENT: No, sir, they have verbal symbols and visual representations.

GUMMIDGE: You’re on your way. For your final exam, read and commit to memory the 23rd Psalm Jargonized by Alan Simpson, president of Vassar College.

STUDENT (droning): “The Lord is my external-internal integrative mechanism. I shall not be deprived of gratifications for my viscerogenic hungers or my need-dispositions. He motivates me to orient myself towards a nonsocial object with effective significance.”

The student falls into a dreamlike trance during which Professor Gummidge tiptoes off and is replaced by the Rev. Mr. Logos, who continues the psalm.

LOGOS: “He positions me in a nondecisional situation. He maximizes my adjustment . . .” (As the student wakes up): I’m the Reverend Mr. Logos. Bless you, my son.

STUDENT: I see you’re wearing a turned-around collar and a yarmulke. Just what is your religion?

LOGOS: I am a theologian. Does that answer you?

STUDENT: No.

LOGOS: Splendid. How would you refer to a priest disagreeing with a minister?

STUDENT: As two guys arguing?

LOGOS: No, no, no! Religious leaders never argue, they have dialogues, or I-Thou relationships.

STUDENT: If their studies are mainly about Jesus?

LOGOS: They are Christocentrically oriented. If they are interpreting the Bible, hermeneutics is the term.

STUDENT: Can you predict what words will be In for the theological year ahead?

LOGOS: Certainly. Demythologizing, optimism, theology of hope, engage and commitment.

STUDENT: I like dialectic theology and conceptualism.

LOGOS: Forget them. They’re all Out. Concentrate on phenomenology, sociological inspiration, ethical activism, crisis of authority.

STUDENT: Suppose someone realizes that I don’t have the faintest idea what I’m talking about?

LOGOS: Then accuse him of objectification. If he doesn’t go away, ask him what he did before he got religion, before his ultimate faith-concern, or better still, Selbstverständnis.

STUDENT: But that’s not even English.

LOGOS: All the better. Many influential theologians wrote in German—Bultmann, Bonhoeffer, Barth—and German not only offers us a chance to obfuscate, it adds a tangy foreign flavor. For instance, there is Historic, meaning bare facts, Geschichte, meaning interpretive history.

STUDENT: Sort of like the difference between The World Almanac and Toynbee.

LOGOS: Remember Gummidge’s Law: don’t clarify!

STUDENT: Sorry.

LOGOS: Don’t let it happen again. Vorverständnis is one of my favorites. It means presupposition. Wissenschaft is far better than saying simply discipline or science, and anxiety sounds much deeper if you say Angst. If you grow weary of German, there is always Greek—almost everyone has seen Never on Sunday—with such splendid specimens as kerygma (message of the Scriptures) and agape (divine love).

STUDENT (writing furiously): Are you sure Jargon really works? In religion, I mean?

LOGOS: Does it? I quote from a distinguished cleric: “I can’t make heads or tails out of a great deal of what Tillich says.” The confessor is Dr. Billy Graham himself.

At this, the Rev. Mr. Logos is borne away by the laity to edit a book of his sermons entitled Through Exegesis and Hermeneutics We Arrive at Kerygma. In his place steps Dr. Beazle, who takes the student’s blood pressure, temperature, hemoglobin count and wallet.

BEAZLE: Now what kind of medical career do you want, physical or psychiatric?

BEAZLE: Now what kind of medical career do you want, physical or psychiatric?

STUDENT: I don’t know. I never thought about it.

BEAZLE: That’s a good start. Suppose we begin with plain everyday medicine. Was it not Herman Melville who wrote: “A man of true science uses but few hard words, and those only when none other will answer his purpose; whereas the smatterer in science thinks that by mouthing hard words he proves that he understands hard things.” Now you don’t want to be an ordinary man of true science when you can be a full-fledged Smatterer, do you?

STUDENT: I guess not.

BEAZLE: Very well, remember never to let the patient be fully aware of what is wrong. Even tonsillitis can be described as a malign hypertrophied condition that affects nares and pharynx and may result in paraphonia clausa. It was I, you know, who wrote the sign seen in hospitals: “Illumination is required to be extinguished on these premises on the termination of daily activities.”

STUDENT: Which means—

BEAZLE: Put out the lights when you leave.

STUDENT: Marvelous.

BEAZLE: It was nothing, really. We medical men have been confounding patients for years. As far back as 1699, the physician and poet Samuel Garth wrote: “The patient’s ears remorseless he assails/Murders with jargon where his medicine fails.” Still, physical medicine is nothing compared with psychiatry. There’s where we Jargonists truly have our day. Suppose a man loses his wife and is unable to love anyone because he is sad. What do I tell him?

STUDENT: Cheer up, there are lots of fish in the—?

BEAZLE (interrupting): Of course not. I intone: You have suffered an object loss in which you had an over-cathesis of libido and have been unable to decathect the libido and invest it in a new object. Do you follow me?

STUDENT: I think so.

BEAZLE: Then be warned: the public is on our trail; they now have learned the meanings of the “oses” and the “itises.” You had better replace them with “inadequacies,” and “dependencies,” tell the man who acts out fantasies that he is “role playing,” speak of the creation of a child as “exclusive electivity of dynamic specificity.”

STUDENT: And when the child is born?

BEAZLE: His development proceeds through “mutual synthesis carried on through a functional zone of mutuality.”

STUDENT: In short, he grows up.

BEAZLE: In long, he proceeds in a continuous unidirectional ever-varying interplay of organism and environment.

STUDENT: If a patient is unhappy?

BEAZLE: He is having an identity crisis.

STUDENT: But suppose he’s just unhappy?

BEAZLE: No one is just unhappy. Psych harder!

STUDENT: I’ll start immediately. I will follow Lionel Trilling’s dictum: no one will fall in love and get married as long as I’m present.

BEAZLE: What will they do?

STUDENT: Their libidinal impulses being reciprocal, they will integrate their individual erotic drives and bring them within the same frame of reference. How am I doing?

BEAZLE: Not badly, but I can still understand you.

STUDENT: Sorry. Day by day I will grow more obscure, until my patients and I completely fail to communicate.

BEAZLE: Oh, if only I could believe that! Smog, confuse, obfuscate!

He exits, to invent a cure for clarity and lucidity which he will sell to nine leading pharmaceutical firms. Mr. Flap and General Redstone come forward.

FLAP: Order of magnitude, expedite, implement, reorient, interoccupational mobility, mission oriented—

REDSTONE: Component forces, readiness levels, destruct—

STUDENT: Excuse me—

REDSTONE (ignoring him): Credibility, paramilitary department—wide contingency plans, pre-emptive war, scenario, remote area conflict. . .

FLAP: Expedite, channels, maximize, bureau potential—

STUDENT: Gentlemen, please, I—

DEAN: It’s no good, son. Once the civilian and the military start arguing, it can go on for years.

REDSTONE: Circular error probability, target systems, pipeline requirements, deterrent gaps . . . counterinsurgency . . . soft target . . .

The general grinds to a halt. Two enlisted men enter, paint him a neutral olive drab and carry him off to the Pentagon, where he will replace a computer.

FLAP (running down): Extended care facilities . . . oligopoly . . . input . . . phasein . . . interlocking intervention . . . (He creaks, coughs and crawls into a filing cabinet.)

DEAN (handing the student a diploma printed on sheeplike vinyl): We’ve done all we can for you, son. In George Orwell’s paraphrase: “The race is not to the swift—nor the battle to the strong . . . but time and chance—”

STUDENT: I know. “Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must be taken into account.”

DEAN: Exactly. (Moist of eye, he pats the new graduate on the head.) You can now take your pick of careers in medicine, religion, business and geopolitics—as well as wine-tasting and art criticism. And if you fail at everything, there’s a job for you at Instant College. (Calling after him as the student exits.) And remember, it is better to curse one candle than to light the darkness . . .

He extinguishes the lights, leaving the audience in blackness as

THE CURTAIN FALLS

[Source: ‘Essay: Right you are if you say you are – Obscurely’, Time Magazine, Friday, 30 December, 1966]

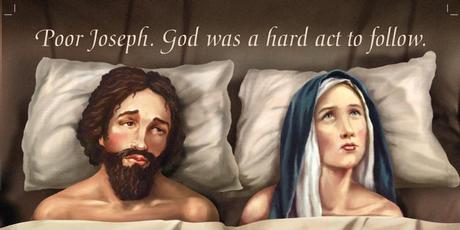

Although I’m writing lectures on Calvin at the moment, brother Martin is rarely far away. So as a bit of fun [read ‘distraction’], I thought I’d check out some of their reflections on the same topic – namely, slander. Unlike Calvin who is typically careful, measured, sober, and rarely amusing, Luther – whether relatively dry or completely off his face – is a brilliant hoot, often careless, never politically correct and always calls a spade a shovel. Isn’t that precisely one of the reasons why we love him so much! Anyway, here he is in near-full swing:

Although I’m writing lectures on Calvin at the moment, brother Martin is rarely far away. So as a bit of fun [read ‘distraction’], I thought I’d check out some of their reflections on the same topic – namely, slander. Unlike Calvin who is typically careful, measured, sober, and rarely amusing, Luther – whether relatively dry or completely off his face – is a brilliant hoot, often careless, never politically correct and always calls a spade a shovel. Isn’t that precisely one of the reasons why we love him so much! Anyway, here he is in near-full swing: Calvin makes what I think is the same basic point, but O how different in tone. Here he is on the ninth commandment (‘You shall not be a false witness against your neighbour’, Exod 20:16):

Calvin makes what I think is the same basic point, but O how different in tone. Here he is on the ninth commandment (‘You shall not be a false witness against your neighbour’, Exod 20:16):