Psalm 88

A Korah Prayer of Heman

1-9 God, you’re my last chance of the day. I spend the night on my knees before you.

Put me on your salvation agenda;

take notes on the trouble I’m in.

I’ve had my fill of trouble;

I’m camped on the edge of hell.

I’m written off as a lost cause,

one more statistic, a hopeless case.

Abandoned as already dead,

one more body in a stack of corpses,

And not so much as a gravestone—

I’m a black hole in oblivion.

You’ve dropped me into a bottomless pit,

sunk me in a pitch-black abyss.

I’m battered senseless by your rage,

relentlessly pounded by your waves of anger.

You turned my friends against me,

made me horrible to them.

I’m caught in a maze and can’t find my way out,

blinded by tears of pain and frustration.

9-12 I call to you, God; all day I call.

I wring my hands, I plead for help.

Are the dead a live audience for your miracles?

Do ghosts ever join the choirs that praise you?

Does your love make any difference in a graveyard?

Is your faithful presence noticed in the corridors of hell?

Are your marvelous wonders ever seen in the dark,

your righteous ways noticed in the Land of No Memory?

13-18 I’m standing my ground, God, shouting for help,

at my prayers every morning, on my knees each daybreak.

Why, God, do you turn a deaf ear?

Why do you make yourself scarce?

For as long as I remember I’ve been hurting;

I’ve taken the worst you can hand out, and I’ve had it.

Your wildfire anger has blazed through my life;

I’m bleeding, black-and-blue.

You’ve attacked me fiercely from every side,

raining down blows till I’m nearly dead.

You made lover and neighbor alike dump me;

the only friend I have left is Darkness.

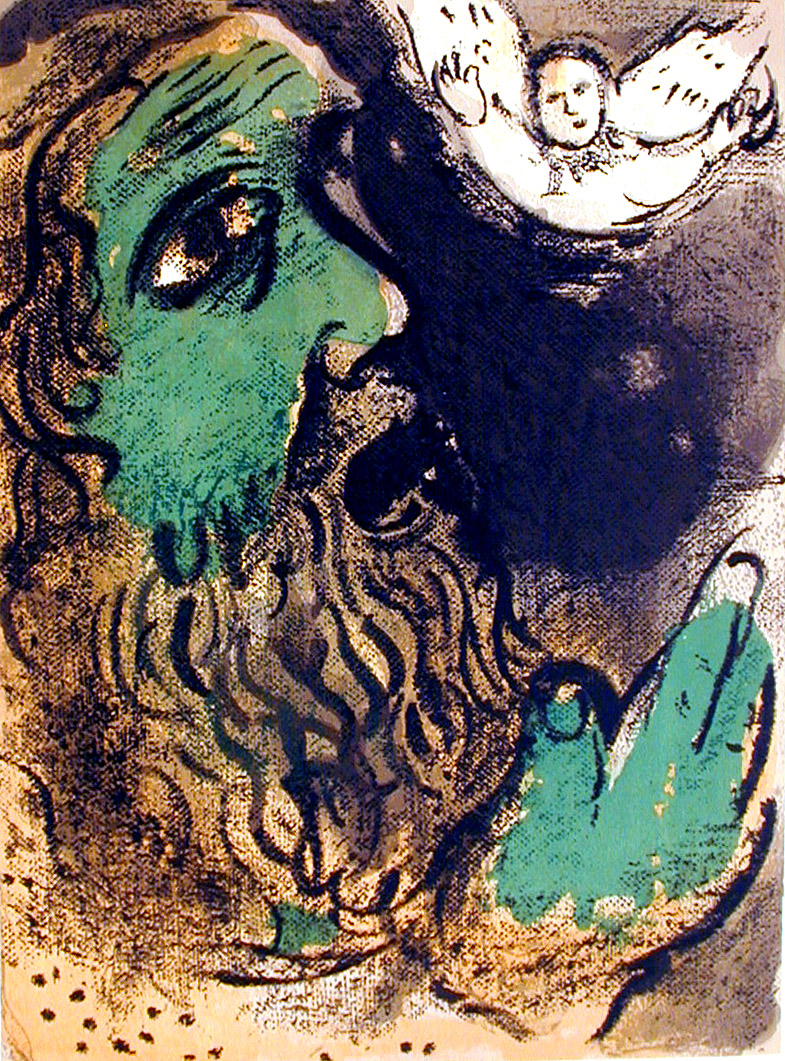

There are a number of striking things about this psalm:

First, there is the honesty: ‘Why, God, do you turn a deaf ear? Why do you make yourself scarce?’

Then there is the fact that cries penned here are not the cheap and thoughtless rage of people who use their darker moments to denounce God from afar. Rather, these cries actively engage with God. In his darkness, Heman the Ezrahite turns not to his friends, nor to the propaganda of the theologians or the atheists. We are here reminded of Simon Peter’s words to Jesus in John 6: ‘Lord, to whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life’ (John 6:68).

And, finally, there is the fact that there is no relief. Heman the Ezrahite begins by crying to the Lord, and he ends in gloom and despair. Most so-called ‘psalms of lament’ begin with discouragement and despair but end in light and joy. But this one begins in gloom and ends in gloom. Along the way, Heman has wrestled with God. And the fact that he brings his lament to God is a reminder that lament, even at its most extreme, might still be an affirmation of faith, a refusal to let go of God.

Despite his crying out to God, Heman feels unheard (vv. 2, 14), he feels that he is near death (v. 3), that he is doomed (vv. 4–5), that he has lost all of his friends (v. 8), even that he is under God’s wrath (vv. 7, 16). Worse yet, Heman is convinced that his whole life has been lived under the shadow of death: ‘For as long as I remember I’ve been hurting; I’ve taken the worst you can hand out, and I’ve had it. Your wildfire anger has blazed through my life; I’m bleeding, black-and-blue’.

The psalms ends with the seemingly hopeless declaration: ‘the only friend I have left is Darkness’ (v. 18). Not God; only the darkness.

I’ve been reflecting on this psalm in light of the winter that is now upon us. The heaters and electric blankets in our homes seek to hide the awful reality that we have entered the season of dying, of the end of life, and of the overcoming of light.

And, of course, the Apostle Paul was consistent in his claim that part of the reality of the Christian existence is that we live with a ‘body of death’ (Rom 7). And in 2 Corinthians 4, he talks about the way that we carry the gospel in ‘jars of clay, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power that we carry belongs to God and does not come from us. We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be made visible in our bodies. For while we live, we are always being given up to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus may be made visible in our mortal flesh’.

It seems that whether we like it or not, this is just the way it is. And especially so, perhaps, for ministers of the gospel who carry a unique burden. This was, at least, the view proposed by Ronald Gregor Smith is his unpublished lecture given at the University of Glasgow in 1938 and entitled ‘Preparing for the Ministry’:

‘There are dark times in everyone’s life, times when the terror of being alive comes swooping down like an evil thing, compassing the poor mind with unimaginable tortures, shaking questions from its wings before which the established habits cower and shrink away, and leaving the victim exhausted and apathetic. If these times come only once or twice in a person’s life, then it is possible still to continue with the accustomed things, or if that time first breaks through the crust of routine at the crucial moment of death, it does not matter that the routine is smashed for ever. But to one who is studying for the ministry, these times come not once or twice, but again and again, storming like a black wave breaking on an island fortress, till his defences are battered in and he is utterly exposed to the mercy of the attack … And the pity of it is that from the first day of preparation the young man [as they all were in those days!] is deprived of the only succour he might have: the terror of the Spirit’s visitation. When He comes to him in the night – while the applause of teachers and comrades is still ringing in his ears – and whispers dread simple questions in his ears, then all this training has taught him t5o deny the rightness of these questions. This is mere melancholy, this is useless idealism, this is not how souls are saved. And he turns to his books again, and if he cannot sleep, helps himself with an anodyne, and slays the ghost which came in the guise of the Spirit. But that ghost is truly the Spirit. The young man who abandons this fight is doing a week thing. But if he does not abandon it, he must be prepared to face a living death and a martyrdom of the spirit untold in the lives of the saints. For he is no saint, yet he must fight the fight which only the Spirit can win … it is a fight whose strength is weakness, whose life is the utter nonentity of the person. For the life of it is the Spirit, always and only the Spirit’.

Something of this same truth is picked up too by Frederick Buechner in A Room Called Remember: Uncollected Pieces:

‘“My God, my God, why has thou forsaken me?” As Christ speaks those words, he, too, is in the wilderness. He speaks them when all is lost. He speaks them when there is nothing even he can hear except for the croak of his own voice and, when as far as even he can see, there is no God to hear him. And in a way his words are a love song, the greatest love song of them all. In a way his words are the words we all of us must speak before we know what it means to love God as we are commanded to love him … This is the love that you and I are called to move toward both through the wilderness times on broken legs and through times when we catch glimpses and hear whispers from beyond the wilderness. Nobody ever claimed the journey was going to be an easy one. It is not easy to love God with all your heart and soul and might when much of the time you have all but forgotten his name. But to love God is not a goal we have to struggle toward on our own, because what at its heart the gospel is all about is that God himself moves us toward it even when we believe that he has forsaken us’. (pp. 44–5)

The Bible tells us that death is the great enemy, not only ‘our’ great enemy, but God’s too. The Bible also tells us that Christ succumbed to death, allowed God’s great enemy to bring him into the nothingness which is humanity’s greatest fear, and all the time he trusted in God. Through the nothingness, he trusted in God. The Spirit was there enabling him to trust in God … to make trust possible.

We, of course, live in this time between the times, a life which is – because of the resurrection of Jesus – constituted by hope. Like Jesus, we too face the full brunt of death’s power. And, like Jesus, the Spirit enables us to face the winter of human existence trusting in God … come what may.

A piece of music like Bach’s Suite No.3 In D/Air on a G String oozes with the hope of God, a Romans 8 kind of hope, the kind of hope that enables us to cry out ‘Abba! Father!’, the kind of hope that considers that ‘the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us’, the kind of hope that joins with all the creation in waiting ‘with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God’, the kind of hope that joins with all the creation as it waits to be ‘set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God’. St Paul writes:

‘We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience. Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words. And God, who searches the heart, knows what is the mind of the Spirit, because the Spirit intercedes for the saints according to the will of God. We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose. For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn within a large family. And those whom he predestined he also called; and those whom he called he also justified; and those whom he justified he also glorified’.

It’s that hope which enables us to live in the Winter as if the Spring is coming. And it’s a hope that is witnessed to nicely in Joyce Rupp’s ‘Prayer 49: Winter’, published in Prayers to Sophia: Deepening Our Relationship With Holy Wisdom (p. 114):

Source of Courage for my Soul,

your season of winter teaches me

about the dark season inside of me.

All the old external props fall away in winter,

nothing to rely on except the whisper of faith.

In the light of a summer’s brilliant day,

it is easy to be brave and confident,

but inside of winter, I stumble blindly,

seeking what I so easily fed on in the light.

This winter journey demands steel courage,

firm determination, fierce boldness,

a heart unyielding to the phantoms of fear

and the menacing moans of despair.

When I stay on this inward road,

true abundance becomes known.

Winter shows what summer never could:

the core of what I believe and value,

the sum of who and what I love.

I learn the enormous power of endurance

and the gift of accepting and loving

who I truly am.

Wise Spirit of the Darkness,

take my hand and teach me to be unafraid

of the wild winds of my inner winter.

Lead me through the gloomy valleys

and teach me how to walk in the dark.