- The Centre for Public Christianity (CPX) has posted two recent interviews with Paul Fiddes. And there’s more Fiddes here on ‘The End of the World: A Work in Progress’.

- Frank Rees posts on ‘Christian Freedom’ and a free church.

- John Pilger on why Tony Blair must be arrested.

- A public lecture by Professor Steve Reicher (professor of social psychology at the University of St Andrew’s) titled ‘Beyond the Banality of Evil’. The lecture, which goes for about 85 minutes, critically addresses Hannah Arendt’s hypothesis on the banality of evil arguing that those who commit extreme acts are not aware of the consequences of their actions; rather, they celebrate these consequences as moral.

- Jim Gordon posts on R S Thomas, the Crucified God and the virtue of metaphysical humility.

- Rick Floyd posts on Disability and Grace.

- Kimlyn J. Bender reviews Gunton’s The Barth Lectures. My own review of Gunton’s volume can be read here.

- Sung-Sup Kim reviews David Gibson’s Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth. My own review of this is here.

- Ben Myers, aka Mr Tomato Plant, shares two chapters of his forthcoming Man Booker Prize-shortlisted novel on gelato and the girl who buttons her coat as her ‘dad arrives to close the shop’.

- Here’s two books I’m waiting for: The Pastor: A Memoir by Eugene H. Peterson, and Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom by Peter J. Leithart

- Finally, I’m enjoying U2’s Go Home: Live from Slane Castle.

Author: Jason Goroncy

Stanley Hauerwas on the place and calling of the elderly

‘Our communities depend on memory to understand what makes us who we are. If you think life is fundamentally about consuming and not about such memories, then the elderly have no place in your world. But I believe that the older you get, the more obligations you have to those who are part of your life to remember your mistakes—and the mistakes of the community—so you can be part of the articulation necessary, hopefully to avoid some of those mistakes in the future.

‘Our communities depend on memory to understand what makes us who we are. If you think life is fundamentally about consuming and not about such memories, then the elderly have no place in your world. But I believe that the older you get, the more obligations you have to those who are part of your life to remember your mistakes—and the mistakes of the community—so you can be part of the articulation necessary, hopefully to avoid some of those mistakes in the future.

So everything depends on the assumption that life is made up of wisdom that is derived from these many lives and many judgments over time. We can pass this on to the next generation. My emphasis on the importance of sharing stories is crucial in that regard because stories are contingent on the tellers. The elderly have to become good tellers of the stories that make the community who they are’. – Stanley Hauerwas, ‘For the Faithful, There Is No ‘Florida’

‘April Peepers, Flaubert, and Springsteen’, by Robert Cording

Now that the sun’s hanging around longer,

These first warm evenings bring

The peepers up out of the muck, aroused

By temperatures and a ferocious desire

To peep and trill a hundred times a minute,

Nearly six thousand times a night,

Each wet, shining body a muscle of need

That says faster, louder, faster, louder.

Life, life to have erections, that’s what it’s

All about—that’s Flaubert ringing

In my old ears, some drained chamber

Of the heart pumping again, interrupting

My bookish evening. I should tie myself

To my chair or stopper my ears. But I’m up

And answering my sirens’ call, overcome

By some need to be outside, to be

Part of this great spring upheaval.

In the dark amid their chorus, I hold

A flashlight on a peeper that pulses

Under its skin, its entire body a trill reaching

Toward a silent female, and now I’m calling

To my wife to come out, to hurry,

And when she finds me, I swear I feel as if

I’m shining like something that has come up

From deep under the earth, and singing

It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive.

– Robert Cording, ‘April Peepers, Flaubert, and Springsteen’ in Love Poems and Other Messages for Bruce Springsteen (ed. Bosveld Jennifer; Columbus: Pudding House Publications, 2009), 64.

Stringfellow on masturbation, sex and the search for self

‘[One] who persists into adulthood in the practice of masturbation is likely to be one who remains profoundly immature sexually, fearing actual sexual contact with a partner, becoming and being sexually retarded. The main danger and damage in masturbation is not in the conduct itself, but in the fantasy life that invariably accompanies the conduct. That life will hardly ever be a sexually fulfilling one, and indeed masturbation is probably most obviously another variety of sexual sublimation – one in which the sexual identity and capability of the person remains stalemated, indefinite, confused, and apparently self-contained. Masturbation is not antisocial per se, but the deep suppression of sexuality which it represents will frequently provoke some other superficially nonsexual, antisocial behavior. And even if the sublimation of masturbation is never relieved, either in sexual relationship with another human being or in some antisocial, apparently non-sexual behavior, the real tragedy – the destructive and dehumanizing fact about masturbation – is its obvious unfulfillment and crude futility among the varieties of sexual activity’ …

‘[One] who persists into adulthood in the practice of masturbation is likely to be one who remains profoundly immature sexually, fearing actual sexual contact with a partner, becoming and being sexually retarded. The main danger and damage in masturbation is not in the conduct itself, but in the fantasy life that invariably accompanies the conduct. That life will hardly ever be a sexually fulfilling one, and indeed masturbation is probably most obviously another variety of sexual sublimation – one in which the sexual identity and capability of the person remains stalemated, indefinite, confused, and apparently self-contained. Masturbation is not antisocial per se, but the deep suppression of sexuality which it represents will frequently provoke some other superficially nonsexual, antisocial behavior. And even if the sublimation of masturbation is never relieved, either in sexual relationship with another human being or in some antisocial, apparently non-sexual behavior, the real tragedy – the destructive and dehumanizing fact about masturbation – is its obvious unfulfillment and crude futility among the varieties of sexual activity’ …

‘Such is the mystery of sex and love that what in sex may be dehumanizing, depraved, or merely habitual, may become human, sacramental, and sanctified. For sex to be so great an event as that, it is essential for one to know who he is as a person, to be secure in his own identity, and indeed, to love himself.

Too often sex does not have the dignity of a sacramental even because it is thought to be the means of the search for self rather than the expression and communication of one who has already found oneself and is free from resort to sex in the frantic pursuit of identity. It is wrong to assume that sex is in itself some way of establishing or proving one’s identity or any resolution of the search for selfhood. One who does not know oneself and seeks to find oneself in sexual experience with another will neither find self nor will he respect the person of a sexual partner. Often enough, the very futility of the search for identity in sex will increase the abuse of both one’s own self and one’s partner. The pursuit of identity in sex ends in destruction, in one form or another, for both the one who seeks oneself and the one who is used as the means of the search. No one may show another who he is or she is; no one may give another life; no one can save another.

How then shall one discover who one is as a human being if sex provides neither the means nor the answer? And how shall one be emancipated from the power of sin in sex and in other realms as well?

In Christ.

In Christ. That means in beholding Christ who is in his own person the true human, the person living in the state of reconciliation with God, with himself, with all men, with the whole creation.

In Christ. That means in discerning that God ends the search for self by himself coming in this world in search of men. For the person, [sic] who knows that he has been found by God no longer has to find self.

In Christ. That means in surrendering to the presence and power of death in all things including sex and , in that event, in the very midst of death, receiving a new life free from the claim of death.

In Christ. That means in accepting the fact of God’s immediate and concretely manifest love for human life, including one’s own little life. Finding, then, that one’s own life is encompassed in God’s love for the world.

In Christ. That means in knowing that in the new life which God gives to humans there is no more a separation between who a person is and what a person does. That which one does, in sex or anything else, is a sign of who one is. All that one does become sacraments of new life.

In Christ. That means in realizing radical fulfillment as a person in the life of God in this world; such radical fulfillment that abstinence in sex is a serious option for a Christian though it is never a moral necessity.

In Christ. That means in enjoying God’s love for all humanity and all things in each and every event or decision of one’s own life.

In Christ. That means in confessing that all life belongs to God, and but for him there is no life at all’.

– William Stringfellow, Instead of Death (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2004), 50–1, 54–5.

July bests …

Hannah’s Child: A Theologian’s Memoir by Stanley Hauerwas; White on Black by Ruben Gallego; Les Murray: A Life in Progress by Peter F. Alexander; Metamorphosis and Other Stories by Franz Kafka; The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram” 1910–1912 by Roald Amundsen; On Human Worth: A Christian Vindication of Equality by Duncan B. Forrester; God’s Being is in Becoming: The Trinitarian Being of God in the Theology of Karl Barth by Eberhard Jüngel; Prayers Plainly Spoken by Stanley Hauerwas.

Through the iPod:

Life in Slow Motion by David Gray; Sunshine on Leith by The Proclaimers; Telling Stories by Tracy Chapman; Masterpieces by Bob Dylan; Complete Recordings by Robert Johnson; In Person & On Stage by John Prine; The Age of Miracles by Mary-Chapin Carpenter; I and Love and You by The Avett Brothers; Mingus Ah Um by Charles Mingus; 11:11 by Rodrigo y Gabriela; Open Sesame by Freddie Hubbard; 100 Miles From Memphis by Sheryl Crow; Songs From The Heart by Celtic Woman; The Imagine Project by Herbie Hancock; Sweet and Wild by Jewel; Heart and Soul by Kenny G; Need You Now by Lady Antebellum; Revolution by Miranda Lambert; Journey to the One by Pharoah Sanders; Fearless by Taylor Swift; Monk’s Dream by Thelonious Monk; Backatown by Trombone Shorty; Sigh No More by Mumford & Sons; Go by Dexter Gordon; April Uprising by The John Butler Trio; Intriguer by Crowded House.

On the screen:

The Road [2009]. (BTW: The worst flick I saw this month was The Lovely Bones [2010])

Eating Out:

Catlins Café: The best lunch I’ve had out in many moons. Remember those burgers we used to eat in the seventies? I found them again here. Soooo good. The food in this wee Owaka café was brilliant, the coffee was very nice, and the new hosts – Aileen & Steve Clarke – are delightful … friendly, but not ‘in-ya-face’ kind of friendly. If you’re in the Catlins, you ought consider popping in for a feed. They also run some accommodation. And just in case you’re wondering, I’m not getting paid for this wee plug. And if you do visit the area, make sure you get along to Nugget Point, one of my favourite bits of coastline in the world.

Hauerwas on Christian Ministry and Speaking Christian

![]() ‘God knows what possesses anyone to enter the ministry in our day. The lack of clarity about what makes Christians Christian, what makes the church the church, and continuing ambiguity in our diverse denominations about ordination itself should surely make anyone think twice about becoming a minister. Moreover the lack of consensus about what it might mean for anyone to act with authority in our society and the church cannot help but make those of us who are not ministers wonder about the psychological health of those who tell us they are called to the ministry.

‘God knows what possesses anyone to enter the ministry in our day. The lack of clarity about what makes Christians Christian, what makes the church the church, and continuing ambiguity in our diverse denominations about ordination itself should surely make anyone think twice about becoming a minister. Moreover the lack of consensus about what it might mean for anyone to act with authority in our society and the church cannot help but make those of us who are not ministers wonder about the psychological health of those who tell us they are called to the ministry.

Too often I fear the ministry is understood by many Christians as well as many who become ministers, to be but one expression of the more general category of something called a “helping profession.” A minister is a social worker with “a difference.” “The difference” is thought to have something to do with God, but it is not clear exactly what difference that difference is to make for the performance of your office.

As a result many who enter the ministry discover after a few years of doing the best they can to meet the expectations of those they serve— expectations such as whatever else you may do you should always be nice—end up feeling as if they have been nibbled to death by ducks. They do so because it is assumed that since pastors do not work for a living those whom the minister serves, or at least those who pay them, can ask the minister to be or do just about anything. Though it is often not clear how what they are asked to do is required by their ordination vows, those in the ministry cannot say “no” because it is not clear what their “job” is in the first place.

Many in the ministry try to protect themselves from the unlimited demands and expectations of their congregations by taking refuge in their families, some alternative ministry such as counseling, or, God help us, a hobby. Such strategies may work for a while, but often those who employ these strategies discover that no spouse can or should love another spouse that much; that even after you have done C.P.E. you are still stuck with the life you had before you were trained in C.P.E.; and a hobby turns out to be just that—a hobby.

The failure of such strategies, I think, throws some light on clergy misconduct. I wish I could attribute the sexual misconduct characteristic of some Methodist clergy to lust, but I fear that most people in the Methodist ministry do not have that much energy. I think the problem is not lust, but loneliness. Isolated by the expectations of the congregation, or the challenge of developing friendships with some in the church without those friendships creating divisions in the church, too often results in a profound loneliness for those in the ministry. Unfortunately, the attempt to overcome that loneliness can take the form of inappropriate behavior.

There is another alternative. You can become a scold urging the church to become more socially active in causes of peace and justice. This may earn you the title of being “prophetic,” but such a strategy may contribute to the incoherence of the ministerial task. For it is not at all clear why you needed to be ordained to pursue causes of peace and justice. It is a great challenge for ministers who would lead their congregations to be more socially active to do so in a manner that does not result in the displacement of worship as the heart of the church.

… what you have learned to do in seminary is read. By learning to read you have learned to speak Christian. That you have learned to read and speak means you have been formed in a manner to avoid the pitfalls I have associated with the contemporary ministry. For I want to suggest to you that one of the essential tasks of those called to the ministry in our day is to be a teacher. In particular, you are called to be a teacher of language. I hope to convince you that if you so understand your task, you will discover that you have your work cut out for you. But that is very good news because you now clearly have something to do.

Yet in the book of James (3:1-5) we are told:

not many of you should become teachers, my brothers and sisters, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness. For all of us make many mistakes. Anyone who makes no mistakes in speaking is perfect, able to keep the whole body in check with a bridle. If we put bits into the mouths of horses to make them obey us, we guide their whole bodies. Or look at ships: though they are so large that it takes strong winds to drive them, yet they are guided by a very small rudder wherever the will of the pilot directs. So also the tongue is a small member, yet it boasts of great exploits.

The problem, according to James, is no one has found a way to tame the tongue. Because the tongue cannot be tamed it becomes a “restless evil, full of deadly poison.” The tongue is the source of discord because it at once makes it possible to bless the Lord and Father yet curse those who are made in the image of God. That we bless and we curse from the same mouth is but an indication of how dangerous the tongue is for those who have learned God will care for his world through patient suffering.

If James is right, and I certainly think he is, then how can I suggest to you that if you are to serve the church well in the ministry you must become a teacher and, in particular, a teacher of a language called Christian? I do so because I think the characterization of the challenges facing those going into the ministry is the result of the loss of the ability of Christians to speak the language of our faith. The accommodated character of the church is at least partly due to the failure of the clergy to help those they serve know how to speak Christian. To learn to be a Christian, to learn the discipline of the faith, is not just similar to learning another language. It is learning another language.

But to learn another language, to even learn to speak well the language you do not remember learning, is a time-consuming task. You are graduating from seminary, which I assume means that you have begun to learn how to speak as well as teach others how to talk, as we say in Texas, “right.” For as I suggested there is an essential relation between reading and speaking—it is through reading that we learn how to discipline our speech so that we say no more than needs to be said. I like to think that seminaries might be best understood as schools of rhetoric where, as James suggests, our bodies—and the tongue is flesh—are subject to disciplines necessary for the tongue to approach perfection.

That the tongue is flesh is a reminder that speech is, as James suggests, bodily. To speak well, to talk right, requires that our bodies be habituated by the language of the faith. To be so habituated requires constant repetition. Without repetition—and repetition is but another word for the worship of God—we are in danger of losing the grammar of the faith. At least part of your task as those called to the ministry is to help us, as good teachers do, acquire the habits of speech through the right worship of God’.

– Stanley Hauerwas, ‘Speaking Christian: A Commencement Address for Eastern Mennonite Seminary’, The Mennonite Quarterly Review 84 (2010), 441–44.

William Stringfellow, Instead of Death – Part IV

In Instead of Death, Stringfellow offers us a wonderful wee statement about conformity:

In Instead of Death, Stringfellow offers us a wonderful wee statement about conformity:

‘Who are you if you are just like everybody else? I will tell you plainly who you are – you are nobody! If you are a conformist just for the sake of being that, it is as if you did not exist in any significant, personal, or human way whatever. It is no real popularity that you gain if your own popularity is suffocated in the effort to conform. You cannot be popular, much less accepted and loved – which involves a different thing than simple popularity – if you are anonymous, and yet it is anonymity into which conformity invites you. If you are a conformist, if you look and act and talk like everybody else, you are nobody; and if you are nobody you might as well be dead, since you are already dead in principle’. (p. 47)

Wipf & Stock have offered readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem 40% off the retail price of any of the Stringfellow volumes. To obtain the 40% discount, just include the coupon code STRINGFELLOW with your order.

Jim Wallis in Dunedin

The Centre for Theology and Public Issues is hosting Jim Wallis, founder and CEO of the Sojourners Community in Washington DC, for an event in Dunedin on Tuesday 28 September. He will be keynote speaker at a conference on ‘Faith, Ethics and Public Life’ as well as deliver the Howard Paterson Memorial Lecture in Public Theology. The venue is to be held at First Church, in Moray Place.

The Centre for Theology and Public Issues is hosting Jim Wallis, founder and CEO of the Sojourners Community in Washington DC, for an event in Dunedin on Tuesday 28 September. He will be keynote speaker at a conference on ‘Faith, Ethics and Public Life’ as well as deliver the Howard Paterson Memorial Lecture in Public Theology. The venue is to be held at First Church, in Moray Place.

Tickets for the full conference, priced at $20 ($15 for students, beneficiaries & U-16s), can be booked online. The Howard Paterson Lecture is open to all the public, though space priority will be given to those who have booked for the whole conference.

Enquiries relating to this event can be made via email, or by calling +64 (0)3 479 8450, or by writing to The Centre for Theology and Public Issues, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054.

Around: ‘Love seeketh not itself to please’

- Stanley Hauerwas and the university

- Richard Hays on the word of reconciliation

- Byron Smith shares a great quote from Karl Rahner on ‘Christian pessimism’

- John Pilger on ‘Julia Gillard, the new warlord of Oz’

- Walter Kasper on the regret of no shared communion

- Elliott Prasse-Freeman on Retaking power in Burma (Part I)

- Carol Howard Merritt on What Causes Pastors to Burnout?

- J.R. Daniel Kirk shares a parents prayer

- Kim Fabricius shares a wonderful sermon on baptism

- Sung-Sup Kim reviews David Gibson’s Reading the Decree: Exegesis, Election and Christology in Calvin and Barth

- Ben Myers is completely uninterested in ‘being a real man’

- ‘Speaking Christian: A Commencement Address for Eastern Mennonite Seminary’ by Stanley Hauerwas

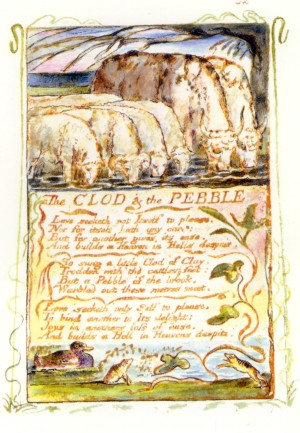

- Finally, here’s some William Blake that I’m enjoying today:

‘The Clod and the Pebble’

‘Love seeketh not itself to please,

Nor for itself hath any care,

But for another gives its ease,

And builds a heaven in hell’s despair.’

So sung a little clod of clay,

Trodden with the cattle’s feet,

But a pebble of the brook

Warbled out these metres meet:

‘Love seeketh only Self to please,

To bind another to its delight,

Joys in another’s loss of ease,

And builds a hell in heaven’s despite.’

Why the floorboards are humming at our place …

Here’s what we’re digging at our place at the moment: Ali Mills singing Waltjim Bat Matilda and Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu singing Wiyathul.

William Stringfellow, Instead of Death – Part III

Chapter Three of Instead of Death is titled ‘Sex and the Search for Self’. Here, the issue is not pleasure or lust but concerns personal identity under the Word of God. Stringfellow’s thesis here is that ‘the search for self is the most characteristic aspect of sex’ (p. 37). And this too is the ‘very theme of the gospel’ (p. 38). Throughout this chapter, he makes the ‘radical’ assumption that people both inside and outside the church are doing it, and nearly doing it, and that sexuality is an element of every human transaction or communication, even when nothing happens to ‘dramatize the fact’. And so he laments the ‘conventional denunciations’ of sex heard so often in the church – of sex as sin and as some something ‘foul or dirty or animalistic’. ‘Nothing that has ever been done in a bedroom, in the back seat of a car, or, for that matter, in a brothel is beyond the scope of the gospel and, therefore, beyond the Church’s care for the world. The fantasies, fears, and fairy tales associated with sex must be dispelled so that, within the Church, sex is admitted, discussed, and understood with intelligence, maturity, compassion, and, most of all, a reverence for the ministry of Christ in restoring human life to human beings’ (pp. 38–9). Stringfellow returns to play this melody later on, this time in regard to pornography and its associated secrecy:

Chapter Three of Instead of Death is titled ‘Sex and the Search for Self’. Here, the issue is not pleasure or lust but concerns personal identity under the Word of God. Stringfellow’s thesis here is that ‘the search for self is the most characteristic aspect of sex’ (p. 37). And this too is the ‘very theme of the gospel’ (p. 38). Throughout this chapter, he makes the ‘radical’ assumption that people both inside and outside the church are doing it, and nearly doing it, and that sexuality is an element of every human transaction or communication, even when nothing happens to ‘dramatize the fact’. And so he laments the ‘conventional denunciations’ of sex heard so often in the church – of sex as sin and as some something ‘foul or dirty or animalistic’. ‘Nothing that has ever been done in a bedroom, in the back seat of a car, or, for that matter, in a brothel is beyond the scope of the gospel and, therefore, beyond the Church’s care for the world. The fantasies, fears, and fairy tales associated with sex must be dispelled so that, within the Church, sex is admitted, discussed, and understood with intelligence, maturity, compassion, and, most of all, a reverence for the ministry of Christ in restoring human life to human beings’ (pp. 38–9). Stringfellow returns to play this melody later on, this time in regard to pornography and its associated secrecy:

‘If sex in all of its meanings, practices, and rituals is not in the open – frankly recognized, intelligently considered, and compassionately dealt with – then what is to be expected except that sex will be the subject of gossip, rumor, escapism, fantasy, and the lure of that which is forbidden? Recourse to pornography among adolescents is, as far as I can discern, far less the consequence of racketeer activities or abnormal adolescent preoccupation with sex than of the fear of candor about sex among adults, including parents and pastors’. (p. 50)

Stringfellow rightly names the heresy called ‘Christian marriage’ as a ‘vain, romantic and unbiblical’ concept, as pure fiction, and as ridiculous as the notion of a ‘Christian nation’ or a ‘Christian lawyer’ or a ‘Christian athlete’, or, we might add, ‘Christian music’. What might a ‘Christian’ crotchet look and sound like?! These are, like marriage, realities of the fallen life of the world, inherently secular, and subject to the power of death. ‘They are’, Stringfellow writes, ‘aspects of the present, transient, perishing existence of the world’ (p. 41). That clergy are licensed by the State to perform the functions of a civil magistrate only adds to the confusion about ‘Christian marriage’, and, Stringfellow claims, ‘greatly compromises the discretion of the clergy as to whom they shall marry’ (p. 42).

Wipf & Stock have offered readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem 40% off the retail price of any of the Stringfellow volumes. To obtain the 40% discount, just include the coupon code STRINGFELLOW with your order.

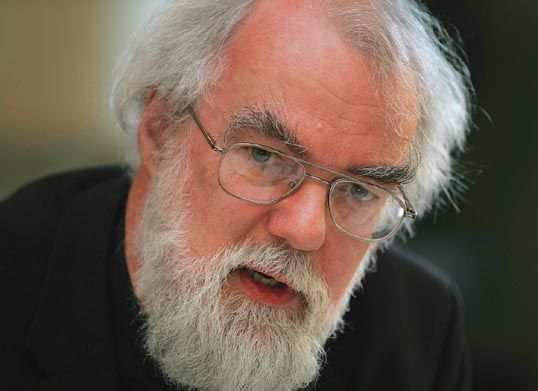

Rowan Williams on forgiveness (and some other stuff)

Rowan Williams is in Stuttgart where he has just has delivered the keynote address at the 11th Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation. The theme of the Assembly is ‘Give us this day our daily bread’. Part of Archbishop Williams’ address addressed the topic of forgiveness:

Rowan Williams is in Stuttgart where he has just has delivered the keynote address at the 11th Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation. The theme of the Assembly is ‘Give us this day our daily bread’. Part of Archbishop Williams’ address addressed the topic of forgiveness:

‘The person who asks forgiveness is a person who has renounced the privilege of being right or safe; he has acknowledged that he is hungry for healing, for the bread of acceptance and restoration to relationship. But equally the person who forgives has renounced the safety of being locked into the position of the offended victim; he has decided to take the risk of creating afresh a relationship known to be dangerous, known to be capable of causing hurt. Both the giver and the receiver of forgiveness have moved out of the safety zone; they have begun to ask how to receive their humanity as a gift.

Forgiveness is one of the most radical ways in which we are able to nourish one another’s humanity. When offence is given and hurt is done, the customary human response is withdrawal, the reinforcing of the walls of the private self, with all that this implies about asserting one’s own humanity as a possession rather than receiving it as gift. The unforgiven and the unforgiving cannot see the other as someone who is part of God’s work of bestowing humanity on them. To forgive and to be forgiven is to allow yourself to be humanised by those whom you may least want to receive as signs of God’s gift; but this process is intrinsically connected with the prayer for daily bread. To deny the possibilities of forgiveness would be to say that there are those I have no need of because they have offended me or because they have refused to extend a hand to me.

To forgive is clearly the mark of a humanity touched by God – free from anxiety about identity and safety, free to reach out into what is other, as God does in Jesus Christ. But it may be that willingness to be forgiven is no less the mark of a humanity touched by God. It is a matter of being prepared to acknowledge that I cannot grow or flourish without restored relationship, even when this means admitting the ways I have tried to avoid it. When I am forgiven by the one I have injured, I both accept that I have damaged a relationship, and accept that change is possible. And if the logic of the Lord’s Prayer is correct, that acceptance arises from and is strengthened by our own freedom to bring about the change that forgiveness entails.

Forgiveness is the exchange of the bread of life and the bread of truth; it is the way in which those who have damaged each other’s humanity and denied its dignity are brought back into a relation where each feeds the other and nurtures their dignity. It is a gross distortion of forgiveness that sees it as a sort of claim to power over the other – being a patron or a benefactor towards someone less secure. We should rather think of those extraordinary words in the prophecy of Hosea (11.8-90) about the mercy of God: ‘How can I give you up, O Ephraim? For I am God and not a mortal’. To forgive is to share in the helplessness of God, who cannot turn from God’s own nature: not to forgive would be for God a wound in the divine life itself. Not power but the powerlessness of the God whose nature is love is what is shown in the act of forgiving. The believer rooted in Christ shares that powerlessness, and the deeper the roots go the less possible it is not to forgive. And to be forgiven is another kind of powerlessness – recognising that I cannot live without the word of mercy, that I cannot complete the task of being myself without the healing of what I have wounded. Neither the forgiver nor the forgiven acquires the power that simply cuts off the past and leaves us alone to face the future: both have discovered that their past, with all its shadows and injuries, is now what makes it imperative to be reconciled so that they may live more fully from and with each other …

But to speak in these terms of bread and forgiveness and the future presses us towards thinking more about the act in which Christians most clearly set forth these realities as the governing marks of Christian existence: the Lord’s Supper, the Eucharist. We celebrate this Supper until Christ comes, invoking the Spirit of the coming age to transform the matter of this world into the sheer gift of Christ to us and so invoking the promise of a whole world renewed, perceived and received as gift. This is, supremely, tomorrow’s bread.

But it is so, of course, not as an object fallen from heaven, but precisely as the bread that is actively shared by Christ’s friends; and it is eaten both as an anticipation of the communion of the world to come and as a memorial of the betrayal and death of Jesus. That is to say, it is also a sacrament of forgiveness; it is the risen Jesus returning to his unfaithful disciples to create afresh in them this communion of the new world. The bread that comes down from heaven is bread that is being handled, broken and distributed by a certain kind of community, the community where people recognise their need of absolution and reconciliation with each other. The community that eats this bread and drinks this cup is one where human beings are learning to accept their vulnerability and need as well as their vocation to feed one another.

So we can connect the prayer for daily bread directly to what goes before it as well as after it in the Lord’s Prayer. We ask for the Kingdom to come and for God’s purpose to be realised as it is in the liturgy of heaven, in the heavenly Temple, where our basic calling to love and praise is fulfilled. And in the light of that, we pray for today’s and tomorrow’s bread, for the signs among us of the future of justice and reconciliation, above all as this is shown in mutual forgiveness.

The Lord’s Supper is bread for the world – not simply in virtue of the sacramental bread that is literally shared and consumed, but because it is the sign of a humanity set free for mutual gift and service. The Church’s mission in God’s world is inseparably bound up with the reality of the common life around Christ’s table, the life of what a great Anglican scholar called homo eucharisticus, the new ‘species’ of humanity that is created and sustained by the Eucharistic gathering and its food and drink. Here is proclaimed the possibility of reconciled life and the imperative of living so as to nourish the humanity of others. There is no transforming Eucharistic life if it is not fleshed out in justice and generosity, no proper veneration for the sacramental Body and Blood that is not correspondingly fleshed out in veneration for the neighbour.

If, then, we are called to feed the world – recalling Jesus’ brisk instruction to his disciples to give the multitudes something to eat (Mark 6.37) – the challenge is to become a community that nourishes humanity, a humanity on the one hand open and undefended, on the other creatively engaged with making the neighbour more human. ‘Give us our daily bread’ must also be a prayer that we may be transformed into homo eucharisticus, that we may become a nourishing Body. Our internal church debates might look a little different if in each case we asked how this or that issue relates to two fundamental things – our recognition that we need one another for our own nourishment and our readiness to offer all we have and are for the feeding, material and spiritual, of a hungry world’.

One can read the whole address here.

Need more Rowan? The New Statesman this week ran two other pieces on him: this one on citizenship, and this interview in which Williams talks about religious longing, the Church of England, society and the economy.

William Stringfellow, Instead of Death – Part II

In Chapter Two of Instead of Death, William Stringfellow turns to a reality that affects us all; namely, loneliness. ‘Loneliness’, he writes, ‘is as intimate and as common to humans as death. Loneliness does not respect persons, but inflicts all – men and women, those of status and the derelicts, the adolescents and the old people, the single and the married, the learned and the illiterate, and, one might add, the clergy and the laity’ (p. 23). Stringfellow proceeds to note that loneliness is neither a unique nor an isolated experience, but is rather the ‘ordinary but still overwhelming anxiety that all relationships are lost’ (p. 24). While neither denying nor negating the existence of lives other than the life of the lonely person, ‘loneliness so vividly anticipates the death of such other lives that they are of no sustenance or comfort to the life and being of the one who suffers loneliness’ (pp. 24–5).

In Chapter Two of Instead of Death, William Stringfellow turns to a reality that affects us all; namely, loneliness. ‘Loneliness’, he writes, ‘is as intimate and as common to humans as death. Loneliness does not respect persons, but inflicts all – men and women, those of status and the derelicts, the adolescents and the old people, the single and the married, the learned and the illiterate, and, one might add, the clergy and the laity’ (p. 23). Stringfellow proceeds to note that loneliness is neither a unique nor an isolated experience, but is rather the ‘ordinary but still overwhelming anxiety that all relationships are lost’ (p. 24). While neither denying nor negating the existence of lives other than the life of the lonely person, ‘loneliness so vividly anticipates the death of such other lives that they are of no sustenance or comfort to the life and being of the one who suffers loneliness’ (pp. 24–5).

Stringfellow then names some of the fictions of loneliness: that it is unfilled time, that it can be satisfied in erotic infatuation, and that it can be answered in possession. Of the latter, he writes: ‘At worst the fiction that one’s identity is to be found in another is cannibalistic – a devouring of another; at best it is a possessive, if romantic, manipulation of one by another in the name of love’ (p. 28).

The reason that none of these attempts have the power to answer loneliness, Stringfellow insists, is because they fail to comprehend the severe nature of loneliness – namely, that it is a foretaste of death. Work, excessive drinking, sex, psychotherapy, marriage, positive thinking (otherwise known as self-hypnoses), suicide, self-pity and leisure are all capable of filling the time but not the void. And not even prayer provides any magic solution. Still, it is the last resort:

‘Prayer is nothing you do, prayer is something you are. Prayer is not about doing, but being. Prayer is about being alone in God’s presence. Prayer is being so alone that God is the only witness to your existence. The secret of prayer is God affirming your life. To be that alone is incompatible with loneliness. In prayer you cannot be lonely. It is the last resort’. (p. 31)

In prayer we approach the lonely, unwelcome, misunderstood, despised, rejected, unloved and misloved, condemned, betrayed, deserted and helpless Christ. Only in the radically-lonely Christ who suffered loneliness without despair – and who descended into hell – is the assurance that no one is alone, and the reality and grace of God triumphant over the death that masquerades as loneliness and the loneliness that anticipates death.

‘In the event in which you are alone with your own death – when all others and all things are absent and gone – God’s initiative affirms your very creation and that you are given your life anew. In the moment and place where God is least expected – in the barrenness and emptiness of death – God is at hand. It is in that event that a person discovers it is death which is alone, not he’. (pp. 32–3)

Wipf & Stock have offered readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem 40% off the retail price of any of the Stringfellow volumes. To obtain the 40% discount, just include the coupon code STRINGFELLOW with your order.

William Stringfellow, Instead of Death – Part I

In 1962, Stringfellow was approached by the Christian Education Department of the Executive Council to pen a book for adolescents that would be included in its high school curriculum. Instead of Death, a book with ‘an astonishing career’ (p. 3), represents Stringfellow’s generous response to that request, a book concerned not with death as such but rather upon the historic transcendence of death, i.e. with resurrection from death. Concerning this book, Stringfellow writes:

In 1962, Stringfellow was approached by the Christian Education Department of the Executive Council to pen a book for adolescents that would be included in its high school curriculum. Instead of Death, a book with ‘an astonishing career’ (p. 3), represents Stringfellow’s generous response to that request, a book concerned not with death as such but rather upon the historic transcendence of death, i.e. with resurrection from death. Concerning this book, Stringfellow writes:

‘Instead of Death seeks to cope pastorally with a few issues which confront young people, as well as other persons, in self-conscious individual circumstances. But the theological connection of any of these matters to the ubiquity of the power of death and the redemptive vitality of the word of God in this world applies equally to political affairs and social crises and, moreover, does so in a way which renders apparently private concerns political’ (p. 4).

Throughout the book, Stringfellow recalls his own journeys alongside death – his own unremitting pain and sickness, the deathly institutions, authorities, agencies and bureaucracies with which he engaged as a Harlem lawyer, and the way in which the community of East Harlem helped him to identity the relentless and ruthless structures, procedures and regimes which dehumanise us, and which are as militant and as morally real as that death which visits us in our illness and personal challenge to life. Stringfellow charges that the Church has all-too-often preached an innocuous image of Jesus, a Jesus who demonstrates no real authority over death’s power, and has supposed a distinction between the personal and the public (or political) which undermines the eventfulness and accessibility of the resurrection for every human being in every situation in which death is pervasive, whether that be in realms political, economical, cultural, psychological or personal. To announce the resurrection of Jesus from the dead is to announce the liberation of all of human life from ‘the meaning and purpose of death in loneliness, in sexuality, and in daily work’ (p. 9), three of the six themes that are then taken up throughout the book.

While sin, evil and death are related, Stringfellow warns that we should not confuse with them each other:

‘Death is not the consequence of either evil or sin, nor is death some punishment for evil or sin. Nor is there any such thing as objective evil; that is, some knowledge or idea or principle of evil which people can learn or discover or discern and then, by their own will, do evil or good. If humans knew or could know what is good and what is evil in that sense, then they would be like God himself … What one person or nation considers to be good or evil can never be claimed by that person or nation to be the equivalent or even the approximation of God’s judgment, although persons and nations constantly make just that pretense. They do it as a way of mocking God, as a way of pretending that they can second guess how God will judge their decisions or actions, as a way of asserting that they already know how God will judge themselves and others. That is perilous because only a person who does not believe in God would so seriously usurp and absurdly challenge the freedom of God in judging all persons and all things in the world … Sin is not essentially the mistaken, inadvertent, or deliberate choice of evil by human beings, but the pride into which they fall in associating their own self-interests with the will of God. Sin is the denunciation of the freedom of God to judge humans as it please him to judge them. Sin is the displacement of God’s will with one’s own will. Sin is the radical confusion as to whether God or the human being is morally sovereign in history. And those persons who suppose that they are sovereign exist in acute estrangement in this history, separated from life itself and from the giver of life, from God’. (pp. 18, 19–20)

And from this decision for or against God, for or against life, none are exempt, not even the youngest of persons:

‘Death does not wait for full maturity and adulthood, for infirmity or age, for sickness o weakness to assail human life. The work of death begins at the very moment of birth: death claims every person on the first consciousness of existence. Death does not respect or wait upon the foolish amenities which cause people to hide from their offspring the truth that, for all the ingenuity and capability of human beings, death is present, powerful, and active in every moment, in every event and transaction of human experience. No one is given birth who does not imminently confront the claim of death over his life’. (pp. 20–1)

But neither death nor life-after-death is the last word – that word Stringfellow insists, is Jesus Christ.

Wipf & Stock have offered readers of Per Crucem ad Lucem 40% off the retail price of any of the Stringfellow volumes. To obtain the 40% discount, just include the coupon code STRINGFELLOW with your order.

Paul Fiddes: Eschatology Revisited

In addition to his public lecture at the recent ANZATS Conference, Paul Fiddes, gave two further, and equally stimulating, lectures on the conference theme, ‘The Future of God’. In the first lecture, ‘Shaping a New Creation: Realized and Future Eschatology Revisited’, Professor Fiddes briefly outlined the history of biblical and theological interpretation of realised and future eschatologies in Schweitzer, Dodd, Barth, Bultmann and Cullmann, before turning to Moltmann’s notion of the future as adventus. He noted how for Moltmann, the eschaton is an event in which the future happens ‘to’ time. He drew attention to a postmodern challenge of openness to ‘the event of the other’, before turning to give some shape to his own Moltmannesque proposal – drawing along the way upon Bloch, Jüngel, Derrida, Ricœur, Hartshorne, Vanstone, Rahner, Swinburne, and others – of God and an open future. God’s future, Fiddes insisted, is elastic, allowing space for both God and the creature to shape their future together. God allows those who are loved to share in the making of the future life. In this way, space is made for genuine human response to the life of God, for genuine interaction between God and creature. Love means that creatures and God both make a contribution to their future together. He argued that it is not only the creatures who wait for this end – God does too! And God is ceaselessly calling out possibilities in the imagination of the creature towards the possibilities that God himself has for the future – a future which is genuinely open. ‘The end is open – certain but surprising’. God makes waiting worthwhile precisely because the future is open – both to God’s creative freedom and to the creature’s response. This means that we ought to be ‘expecting the unexpected’. Divine omniscience, Fiddes noted, means that God knows everything that there is to be known. God does not yet know, however, the details of the future because the future is not yet there to be known. The future, therefore, is both open and closed. Its details are uncertain and genuinely open. That the end is the reconciliation of all things unto holy love is, however as sure as God’s self. During the question time following, Fiddes stated that it is not possible to speak either of God or of the eschaton literally. Language reaches its limits here. We are driven to metaphor.

In addition to his public lecture at the recent ANZATS Conference, Paul Fiddes, gave two further, and equally stimulating, lectures on the conference theme, ‘The Future of God’. In the first lecture, ‘Shaping a New Creation: Realized and Future Eschatology Revisited’, Professor Fiddes briefly outlined the history of biblical and theological interpretation of realised and future eschatologies in Schweitzer, Dodd, Barth, Bultmann and Cullmann, before turning to Moltmann’s notion of the future as adventus. He noted how for Moltmann, the eschaton is an event in which the future happens ‘to’ time. He drew attention to a postmodern challenge of openness to ‘the event of the other’, before turning to give some shape to his own Moltmannesque proposal – drawing along the way upon Bloch, Jüngel, Derrida, Ricœur, Hartshorne, Vanstone, Rahner, Swinburne, and others – of God and an open future. God’s future, Fiddes insisted, is elastic, allowing space for both God and the creature to shape their future together. God allows those who are loved to share in the making of the future life. In this way, space is made for genuine human response to the life of God, for genuine interaction between God and creature. Love means that creatures and God both make a contribution to their future together. He argued that it is not only the creatures who wait for this end – God does too! And God is ceaselessly calling out possibilities in the imagination of the creature towards the possibilities that God himself has for the future – a future which is genuinely open. ‘The end is open – certain but surprising’. God makes waiting worthwhile precisely because the future is open – both to God’s creative freedom and to the creature’s response. This means that we ought to be ‘expecting the unexpected’. Divine omniscience, Fiddes noted, means that God knows everything that there is to be known. God does not yet know, however, the details of the future because the future is not yet there to be known. The future, therefore, is both open and closed. Its details are uncertain and genuinely open. That the end is the reconciliation of all things unto holy love is, however as sure as God’s self. During the question time following, Fiddes stated that it is not possible to speak either of God or of the eschaton literally. Language reaches its limits here. We are driven to metaphor.

Fiddes’ final lecture at this meeting was titled ‘Patterns of Hope: Penultimate and Ultimate Eschatology Revisited’. Herein, he outlined John Hick’s pareschatology, and noted that one of the problems with Hick’s eschatology is its ‘highly individualistic’ nature. Again, Fiddes turned to Moltmann, this time outlining Moltmann’s version of millennialism and identifying some of its more unsatisfying features. Drawing this time upon Derrida, Huxley, Graham Ward, Heidegger, Kristeva, Merleau-Ponty, John Robinson, Barth, John Macquarrie, Pannenberg and Whitehead, Fiddes spoke of the way in which the notion of resurrection functions as an image of ultimate eschatology. He spoke too of the unacceptability of any ongoing simultaneity and oppressiveness, and proposed instead an eschatological vision that concerned the healing of time. Penultimate eschatology, he said, has an identity held in the triune God. There must be a penultimate eschatology if our identity is to be preserved, i.e. if God is to keep communion with who we are. When questioned from the floor about the nature of final judgement, Fiddes responded by insisting that final judgement means being confronted with the truth. This, of course, is a painful process, particularly for those who delight in living a lie.

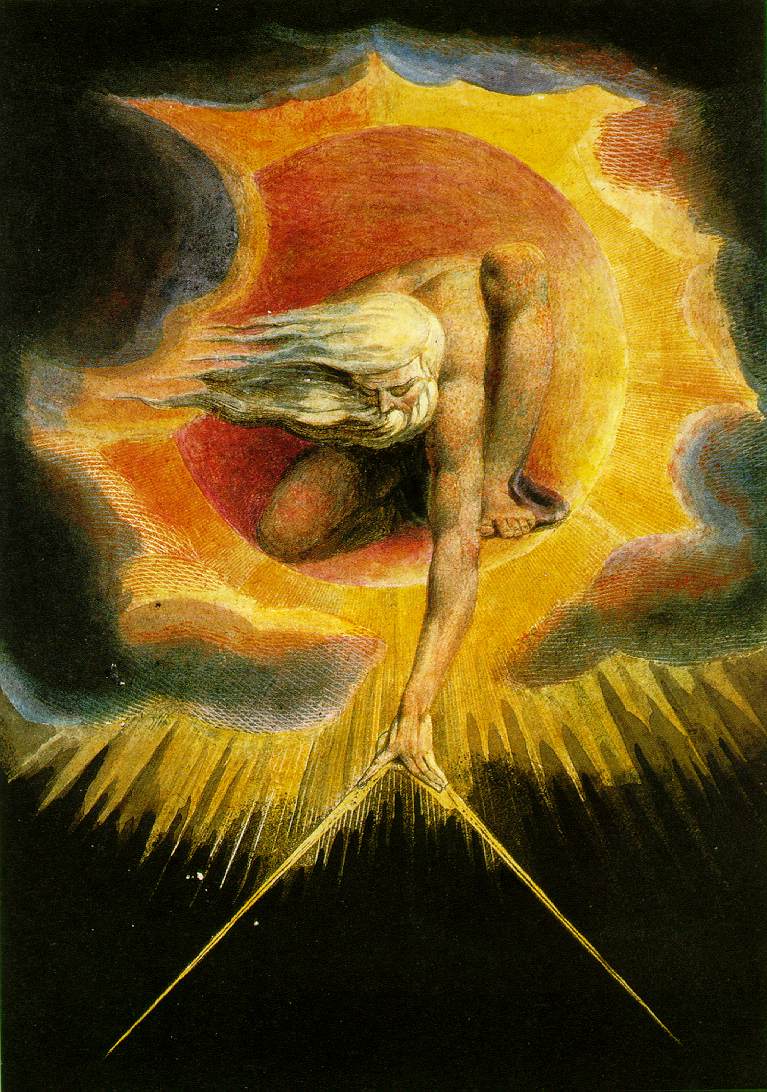

Paul Fiddes, ‘Images of Eternity: A Literary and Theological Enquiry into the Future’

In his public lecture at the recent ANZATS Conference in Melbourne, Paul Fiddes, one of the most stimulating theologians writing today, considered three literary giants – William Shakespeare, William Blake and TS Eliot. He argued that for Blake, eternity is about the wholeness of persons under the aegis of imagination and forgiveness, and that imagination petrifies when reason casts its laws upon it. Of Eliot’s work, Professor Fiddes drew attention to the notion of eternity as the healing of time, and as that which overcomes the division between past, present and future. We were reminded, and that with eloquence typical of the speaker, that God holds and heals the past, the present and the future in the transforming presence of love, and that we never escape from time but time can bring us into a new sphere of love.

In his public lecture at the recent ANZATS Conference in Melbourne, Paul Fiddes, one of the most stimulating theologians writing today, considered three literary giants – William Shakespeare, William Blake and TS Eliot. He argued that for Blake, eternity is about the wholeness of persons under the aegis of imagination and forgiveness, and that imagination petrifies when reason casts its laws upon it. Of Eliot’s work, Professor Fiddes drew attention to the notion of eternity as the healing of time, and as that which overcomes the division between past, present and future. We were reminded, and that with eloquence typical of the speaker, that God holds and heals the past, the present and the future in the transforming presence of love, and that we never escape from time but time can bring us into a new sphere of love.

These are themes with have much occupied Fiddes’ thought in recent years (see, for example, The Creative Suffering of God, The Promised End: Eschatology in Theology and Literature and Freedom and Limit: A Dialogue Between Literature and Christian Doctrine), and around which he is due to lecture further this year. He will be a keynote speaker at ‘The Power of the Word: Poetry, Theology and Life’, a conference held jointly between Heythrop College and the Institute of English Studies, and at the 2010 Biennial Conference of the International Society for Religion, Literature and Culture, to be held at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, between 23–26 September 2010 around the theme ‘Attending to the Other: Critical Theory and Spiritual Practice’.

Acknowledgements

Ruben Gallego’s White on Black was awarded the Russian Booker Prize in 2003. And appropriately so. I thought it one of the most intriguing novels I’ve read this year, one which unrelentlessly invites the reader to think about time and place, loss and irritation, foolishness and music, democracy and wheelchairs, bayonets, books and borscht, and neverness – differently. But it’s the Acknowledgements that I wish to draw attention to here in this post, particularly in light of Ben Myers’ recent splash on book dedications.

Ruben Gallego’s White on Black was awarded the Russian Booker Prize in 2003. And appropriately so. I thought it one of the most intriguing novels I’ve read this year, one which unrelentlessly invites the reader to think about time and place, loss and irritation, foolishness and music, democracy and wheelchairs, bayonets, books and borscht, and neverness – differently. But it’s the Acknowledgements that I wish to draw attention to here in this post, particularly in light of Ben Myers’ recent splash on book dedications.

Gallego concludes his book thus:

‘Thanks to Eve, our Foremother, for eating the apple.

Thanks to Adam, for taking part.

Special thanks to Eve.

Thanks to my grandmother Esperanza for bearing my mama.

Thanks to Ignacio for taking part.

Special thanks to my grandmother.

Thanks to my mama for bearing me.

Thanks to David for taking part.

Special thanks to my mama.

Thanks to my mama for bearing my sister.

Thanks to Sergei for taking part.

Special thanks to my mama.

Thanks to my literature teacher. Once when I was sick, she brought me chicken soup. She brought jam to class, and we ate jam and were perfectly happy. When I wrote compositions, she gave me the highest mark, when she didn’t give me the lowest.

Thanks to Sergei for editing and publishing my first texts.

Special thanks to my literature teacher for the jam.

Thanks to my wives, for having been.

Thanks to my daughters, for having been and being.

Special thanks to my daughters for being.

Thanks to all the women, granddaughters and grandmothers, young and old, beautiful and less beautiful.

Thanks to all the men.

Special thanks to the men for taking part.

Thanks again to my mama.

‘Piping songs of peasant glee’: Around the aether

- Some protest against St Andrews’ appointment of NT Wright.

- NT Wright’s speech, on women bishops, at General Synod.

- Charles Marsh reflects on Bonhoeffer’s time in America.

- Slavoj Žižek’s lecture on Apocalyptic Times.

- Jean-Luc Nancy on Communism.

- The ABC launch an exciting-looking new sight – Religion and Ethics – with pieces by Rowan Williams on resident aliens, Stanley Hauerwas on greed, Paul Griffiths on death, Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im on Islam and human rights, David Novak on Judaism, punishment and torture, and others.

- Emma Wild-Wood on the journal of CMS Evangelist, Apolo Kivebulaya.

- Maria Nugent on the meaning of texts in Aboriginal people’s oral traditions.

- Tarkovsky films now free online.

- Sarah Coakley rethinks the sex crises in Catholicism and Anglicanism, Part 1.

- Archbishop Rowan Williams’ closing sermon at General Synod.

Ten (Draft) Propositions on the Missionary Nature of the Church

1. We commend the motivation which grants missiology a prime locus within ecclesiology, and, conversely, understands ecclesiology within the locus of the missio dei.

1. We commend the motivation which grants missiology a prime locus within ecclesiology, and, conversely, understands ecclesiology within the locus of the missio dei.

2. We commend the claim that the community’s task of bearing witness to Christ is of the esse to the missio ecclesiae.

3. We commend the assertion that the missio ecclesiae finds its genesis and telos in the trinitarian relations ad intra and in the missio dei ad extra.

4. But we reject those articulations which suggest that the divine ontology in se is determined in the missio dei ad extra and so undermine the truth that the missio dei is an action of free grace from Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

5. We commend the intention to bring the conversation about the missio ecclesiae into dialogue with divine election, or what we might call ‘missional election’.

6. We commend the determination that understands the missio ecclesiae as an extension of, and witness to, the divine love.

7. We reject the decision to blur the distinction between the esse and the bene esse of the people of God along missiological lines.

8. We reject those theological programs which would reduce the Church’s raison d’être to the functions of mission.

9. We reject any suggestion that the Church is in a position of self-determination. Founded in baptism, called into being by proclamation, ruled by scripture and nourished by the eucharist, the Church is – and remains – a creatura verbum Dei, a people claimed and kept by God and made one by the vivifying Spirit to worship God in spirit and truth. The Church can be faithful or perfidious to its ontology, it can choose to hear or to be deaf, but its hearing or otherwise does not determine its status or its end. Only its Creator can do this. Again, the Church is not the determination of the creature but of the one God of grace. Jesus’ promise to the apostolic community is that he will remain with it until the very end of the age. These are the words of a faithful lover in unilateral covenant which his beloved. That this lover is as good as his word provides the certainty that the Church – like Israel – is neither optional nor independent nor dispensable to God’s purposes for creation.

10. We ought to be able to say all this without resort to Latin.

‘Much Laughter’, by Robert Cording

Boswell’s only note after an evening with Dr. Johnson.

Boswell’s only note after an evening with Dr. Johnson.

Nothing about the food, the wine, the subjects

Of that night’s passions. Nothing even about

The weather – rain most likely, the damp seeping

Under doors. Just those two words for a night

When everything else slipped into the vacancies

Of the unrecorded. That’s all that’s left. We know

Now the more complete story that Boswell chose

Not to tell: the good doctor’s wearied martyr’s gaze

As he walked the alleyways where the poor remained

Poor, the blind, blind, where the only lesson learned

From suffering was how much better it would be

Not to suffer. We know, too, that Johnson wanted

About this time to rest in God and yet could not

Imagine how to surrender himself to a future

He couldn’t anticipate; he couldn’t help but believe,

To his dismay, that all life needed to go wrong was

The hope it would go right. Too many could not see

How evil fouled the gears of the century’s benign God.

He was headed for another breakdown; Mrs. Thrale

Had already been secretly entrusted with a padlock

And chain to restrain his fits when the time came.

But on this particular evening, happiness must have

Arrived when he least expected it. A few hours

When everyone’s burdens were shouldered, when

There was no tomorrow sprouting its thousand forms

Of grief and humiliation and defeat. Just jokes

And small talk, and wine sweetened with oranges

And sugar tumbling down the doctor’s throat.

A night, perhaps, when all the timorous and beaten

Faces suddenly brightened in their common temple

Of laughter. A night when even a stray black dog

Might have been allowed to lick clean a patron’s

Greasy hands and warm its flea-bitten belly

Near the fire. A night caught in the genius and irony

Of Boswell’s two words – what they left unsaid

And what they say, the simple phrase like a pardon

After our sins have been listened to one by one,

And there is nothing left to remember but “much

Laughter” after another day on earth is done.

– Robert Cording, Common Life: Poems (Fort Lee: CavanKerry Press, 2006), 93–94.