We homo sapiens are, essentially, both a storied people and a story-telling people. So, a basic human question is not primarily, ‘What am I, as an individual, to do or decide?’ but rather, ‘Of what stories do I find myself a part, and thus who should I be?’; for we literally live by stories. The Church, too, understands itself as a pilgrim people, as a people storied on the way, as a people whose very way becomes the material which shapes the narrative that has long preceded it and which is being written with it. It understands that being human never begins with a white piece of paper. As Alasdair MacIntyre rightly reminds us in After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, we never start anywhere. Rather, we simply find ourselves within a story that has been going on long before our arrival and will continue long after our departure. Moreover, Christian community begins with being found in the very act of God’s self-disclosure, an act which, in Jamie Smith’s words, ‘cuts against the grain of myths of progress and chronological snobbery’ and places us in the grain of the universe. And what – or, more properly, who – is disclosed in that crisis of discovery is one who provides memory, unity, identity and meaning to the story of our life. So Eberhard Jüngel: ‘We are not … simply agents; we are not just the authors of our biography. We are also those who are acted upon; we are also a text written by the hand of another’. Hence it is not just any story by which the Church lives but rather a particular story given to it – namely, Israel’s story in which, in the words of R.S. Thomas, it ‘gaspingly … partake[s] of a shifting identity never [its] own’.

We homo sapiens are, essentially, both a storied people and a story-telling people. So, a basic human question is not primarily, ‘What am I, as an individual, to do or decide?’ but rather, ‘Of what stories do I find myself a part, and thus who should I be?’; for we literally live by stories. The Church, too, understands itself as a pilgrim people, as a people storied on the way, as a people whose very way becomes the material which shapes the narrative that has long preceded it and which is being written with it. It understands that being human never begins with a white piece of paper. As Alasdair MacIntyre rightly reminds us in After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, we never start anywhere. Rather, we simply find ourselves within a story that has been going on long before our arrival and will continue long after our departure. Moreover, Christian community begins with being found in the very act of God’s self-disclosure, an act which, in Jamie Smith’s words, ‘cuts against the grain of myths of progress and chronological snobbery’ and places us in the grain of the universe. And what – or, more properly, who – is disclosed in that crisis of discovery is one who provides memory, unity, identity and meaning to the story of our life. So Eberhard Jüngel: ‘We are not … simply agents; we are not just the authors of our biography. We are also those who are acted upon; we are also a text written by the hand of another’. Hence it is not just any story by which the Church lives but rather a particular story given to it – namely, Israel’s story in which, in the words of R.S. Thomas, it ‘gaspingly … partake[s] of a shifting identity never [its] own’.

Back in 1993, Robert Jenson wrote a great little piece titled ‘How the World Lost Its Story’ (First Things 36 (1993), 19–24). He opened that essay with these words:

Back in 1993, Robert Jenson wrote a great little piece titled ‘How the World Lost Its Story’ (First Things 36 (1993), 19–24). He opened that essay with these words:

It is the whole mission of the church to speak the gospel … It is the church’s constitutive task to tell the biblical narrative to the world in proclamation and to God in worship, and to do so in a fashion appropriate to the content of that narrative, that is, as a promise claimed from God and proclaimed to the world. It is the church’s mission to tell all who will listen, God included, that the God of Israel has raised his servant Jesus from the dead, and to unpack the soteriological and doxological import of that fact.

To speak the gospel and, in Jenson’s parlance, to ‘do so in a fashion appropriate to the content of that narrative’, the Church is given a pulpit, a font and a table; in fact, many pulpits, fonts and tables. And these remain the principle ‘places’ where the people of God can expect to hear and to see and to taste and to learn and to proclaim the story into which they have been gathered, redeemed and made an indispensable character. This is not, however, to suggest that these are the only places wherefrom the free and sovereign Lord may speak, nor to aver in any way that the gospel is somehow kept alive by the Church’s attempt to be a story teller, for the story is itself nothing but God’s own free and ongoing history in Jesus. As Jüngel put it in God as the Mystery of the World, ‘God does not have stories, he is history’.  To speak gospel is literally to proclaim God, speech that would be a lie and completely empty were it not the story of God with us, of the saving history which has become part of God’s own narrative, of the world which has, in Jesus Christ, become ‘entangled in the story of the humanity of God’ (Jüngel), a story at core kerygmatic and missionary, and unfinished until all its recipients are included in its text. For, as Jenson has written in his much-too-neglected Story and Promise, the story of Jesus – who is the content of the gospel – ‘is the encompassing plot of all men’s stories; it promises the outcome of the entire human enterprise and of each man’s involvement in it’. To know this man’s story, therefore, is to know not only the story of God but also our own story. Indeed, it is the story that makes human life possible at all. As Jenson would write elsewhere, ‘Human life is possible — or in recent jargon “meaningful” — only if past and future are somehow bracketed, only if their disconnection is somehow transcended, only if our lives somehow cohere to make a story’.

To speak gospel is literally to proclaim God, speech that would be a lie and completely empty were it not the story of God with us, of the saving history which has become part of God’s own narrative, of the world which has, in Jesus Christ, become ‘entangled in the story of the humanity of God’ (Jüngel), a story at core kerygmatic and missionary, and unfinished until all its recipients are included in its text. For, as Jenson has written in his much-too-neglected Story and Promise, the story of Jesus – who is the content of the gospel – ‘is the encompassing plot of all men’s stories; it promises the outcome of the entire human enterprise and of each man’s involvement in it’. To know this man’s story, therefore, is to know not only the story of God but also our own story. Indeed, it is the story that makes human life possible at all. As Jenson would write elsewhere, ‘Human life is possible — or in recent jargon “meaningful” — only if past and future are somehow bracketed, only if their disconnection is somehow transcended, only if our lives somehow cohere to make a story’.

And here we come up against the perennial question of human speech, and it’s back to Jüngel (and to Peter Kline’s article on Jüngel and Jenson) to help me out: ‘The language which corresponds to the humanity of God’, writes Jüngel, ‘must be oriented in a highly temporal way in its language structure. This is the case in the language mode of narration, [or] telling a story’. In other words, if Kline reads Jüngel correctly, Jüngel is suggesting that narrative or story is the mode of human  language which most appropriately corresponds to the form of God’s life among and with us. Commenting on Jüngel, Kline argues that narrative alone witnesses to the change from old to new, can capture the movement and becoming in which God has his being, corresponds to the eschatological event of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and brings ‘the word of the cross’ to expression in a way apposite to us. So Jüngel: ‘God’s humanity introduces itself into the world as a story to be told’. Kline notes that for Jüngel, the church is given a story to tell, but, in Jüngel’s words, it ‘can correspond in [its] language to the humanity of God only by constantly telling the story anew’. God’s humanity ‘as a story which has happened does not cease being history which is happening now, because God remains the subject of his own story . . . God’s being remains a being which is coming’. The community, Kline says, tells only the story of Jesus Christ’s history, and so it constantly looks back to what has happened. Yet the telling of this story is also always new because God’s entrance into human language that once happened continues to happen again and again as Jesus Christ continues to live in the freedom of the Spirit. God is not confined to his once-enacted history, to one language or culture; history does not consume God. So Jüngel again: ‘God who is eschatologically active and who in his reliability is never old [is] always coming into language in a new way’.

language which most appropriately corresponds to the form of God’s life among and with us. Commenting on Jüngel, Kline argues that narrative alone witnesses to the change from old to new, can capture the movement and becoming in which God has his being, corresponds to the eschatological event of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and brings ‘the word of the cross’ to expression in a way apposite to us. So Jüngel: ‘God’s humanity introduces itself into the world as a story to be told’. Kline notes that for Jüngel, the church is given a story to tell, but, in Jüngel’s words, it ‘can correspond in [its] language to the humanity of God only by constantly telling the story anew’. God’s humanity ‘as a story which has happened does not cease being history which is happening now, because God remains the subject of his own story . . . God’s being remains a being which is coming’. The community, Kline says, tells only the story of Jesus Christ’s history, and so it constantly looks back to what has happened. Yet the telling of this story is also always new because God’s entrance into human language that once happened continues to happen again and again as Jesus Christ continues to live in the freedom of the Spirit. God is not confined to his once-enacted history, to one language or culture; history does not consume God. So Jüngel again: ‘God who is eschatologically active and who in his reliability is never old [is] always coming into language in a new way’.

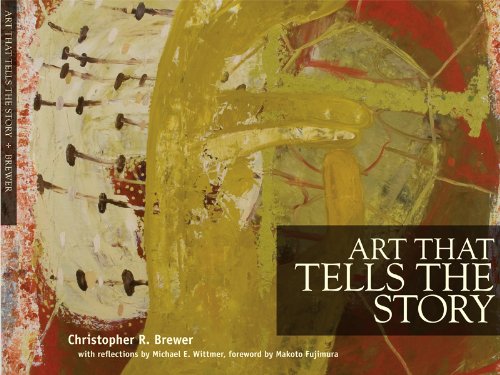

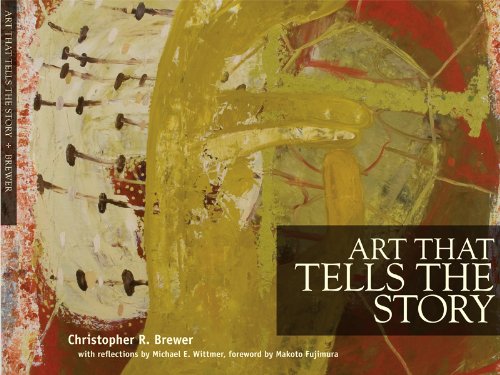

‘Telling the story anew’. ‘God … [is] always coming into language in a new way’. Which brings me to Chris Brewer’s new book, Art that Tells the Story. Others have already summarised the book, so let me simply say that Art that Tells the Story is a freshly-presented and beautifully-produced book which attempts to tell the old, old story … again. Boasting some intriguing prose (by Michael E. Wittmer) and coupled with well-curated images from a diverse array of accomplished visual artists including Jim DeVries, Wayne Forte, Edward Knippers, Barbara Februar, Clay Enoch, Julie Quinn, Michael Buesking and Alfonse Borysewicz, among others, herein, word and image work in concert to open readers up to hear and see again, and to hear and see as if for the first time, the Bible’s story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, inviting – nay commanding!, for the gospel is command – readers to comprehend in this story their own, and to enter with joy into the narrative which is the life of all things. A book this beautiful ought to be in hardback; but may it, all the same, find itself opened and dialogued with next to many coffee mugs, and in good and diverse company. Like its subject, this is one to sit with, to be transformed by, and to share with others.

‘Telling the story anew’. ‘God … [is] always coming into language in a new way’. Which brings me to Chris Brewer’s new book, Art that Tells the Story. Others have already summarised the book, so let me simply say that Art that Tells the Story is a freshly-presented and beautifully-produced book which attempts to tell the old, old story … again. Boasting some intriguing prose (by Michael E. Wittmer) and coupled with well-curated images from a diverse array of accomplished visual artists including Jim DeVries, Wayne Forte, Edward Knippers, Barbara Februar, Clay Enoch, Julie Quinn, Michael Buesking and Alfonse Borysewicz, among others, herein, word and image work in concert to open readers up to hear and see again, and to hear and see as if for the first time, the Bible’s story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, inviting – nay commanding!, for the gospel is command – readers to comprehend in this story their own, and to enter with joy into the narrative which is the life of all things. A book this beautiful ought to be in hardback; but may it, all the same, find itself opened and dialogued with next to many coffee mugs, and in good and diverse company. Like its subject, this is one to sit with, to be transformed by, and to share with others.

Flannery O’Connor once confessed, in Mystery and Manners, that ‘there is a certain embarrassment about being a story teller in these times when stories are considered not quite as satisfying as statements and statements not quite as satisfying as statistics’. ‘But’, she continued, ‘in the long run, a people is known, not by its statements or statistics, but by the stories it tells’. And so the dogged persistence of theologians and artists. Indeed, it is stories – in fact, a particular, if not very short or simple, story – that Brewer’s book is primarily concerned to tell. That his chosen medium is the visual arts reminded me of something that NT Wright once said, and which is, I think, worth repeating:

We have lived for too long with the arts as the pretty bit around the edge with the reality as a non-artistic thing in the middle. But the world is charged with the grandeur of God. Why should we not celebrate and rejoice in that? And the answer sometimes is because the world is also a messy and nasty and horrible place. And, of course, some artists make a living out of representing the world as a very ugly and wicked and horrible place. And our culture has slid in both directions so that we have got sentimental art on the one hand and brutalist art [on] the other. And if you want to find sentimental art then, tragically, the church is often a good place to look, as people when they want to paint religious pictures screen out the nasty bits. But genuine art, I believe, takes seriously the fact that the world is full of the glory of God, and that it will be full as the waters cover the sea, and, at present (Rom 8), it is groaning in travail. Genuine art responds to that triple awareness: of what is true (the beauty that is there), of what will be true (the ultimate beauty), and of the pain of the present, and holds them together as the psalms do, and asks why and what and where are we … And our generation needs us to do that not simply to decorate the gospel but to announce the gospel. Because again and again, when you can do that you open up hermeneutic space for people whose minds are so closed by secularism that they just literally cannot imagine any other way of the world being. I have debated in public … with colleagues in the New Testament guild who refuse to believe in the bodily resurrection and, again and again, the bottom line is when they say ‘I just can’t imagine that’, the answer is, ‘Smarten up your imagination’. And the way to do that is not to beat them over the head with dogma but so to create a world of mystery and beauty and possibility, that actually there are some pieces of music which when you come out of them it is much easier to say ‘I believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit’ than when you went in.

We have lived for too long with the arts as the pretty bit around the edge with the reality as a non-artistic thing in the middle. But the world is charged with the grandeur of God. Why should we not celebrate and rejoice in that? And the answer sometimes is because the world is also a messy and nasty and horrible place. And, of course, some artists make a living out of representing the world as a very ugly and wicked and horrible place. And our culture has slid in both directions so that we have got sentimental art on the one hand and brutalist art [on] the other. And if you want to find sentimental art then, tragically, the church is often a good place to look, as people when they want to paint religious pictures screen out the nasty bits. But genuine art, I believe, takes seriously the fact that the world is full of the glory of God, and that it will be full as the waters cover the sea, and, at present (Rom 8), it is groaning in travail. Genuine art responds to that triple awareness: of what is true (the beauty that is there), of what will be true (the ultimate beauty), and of the pain of the present, and holds them together as the psalms do, and asks why and what and where are we … And our generation needs us to do that not simply to decorate the gospel but to announce the gospel. Because again and again, when you can do that you open up hermeneutic space for people whose minds are so closed by secularism that they just literally cannot imagine any other way of the world being. I have debated in public … with colleagues in the New Testament guild who refuse to believe in the bodily resurrection and, again and again, the bottom line is when they say ‘I just can’t imagine that’, the answer is, ‘Smarten up your imagination’. And the way to do that is not to beat them over the head with dogma but so to create a world of mystery and beauty and possibility, that actually there are some pieces of music which when you come out of them it is much easier to say ‘I believe in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit’ than when you went in.

Art that Tells the Story is grounded upon the premise that artists and theologians can not only help us to see better, but also that like all human gestures toward the truth of things, the work of artists can become an instrument through which God calls for our attention. And here I wish to conclude by re-sounding a call trumpeted by Michael Austin in Explorations in Art, Theology and Imagination:

Theologians must be on their guard against commandeering art for religion, must allow artists to speak to them in their own language, and must try to make what they can of what they hear. What they will hear will tell of correspondences and connections, of similarities, of interactions and of parallel interpretations and perceptions which will suggest a far closer relationship of essence between art and religion than many theologians have been prepared to acknowledge. As the churches at the beginning of the twenty-first century become more fearful and therefore more conservative there may be fewer theologians prepared to take the risks that embracing a truly incarnational religion demands of them. In particular what they hear may suggest to them that their many (often contradictory) understandings of God and redemption and salvation in Christ need to be radically reconsidered if a new world is to be made.

Chris Brewer’s Art that Tells the Story is just such an attempt. It’s good stuff.

Speaking at a Ministers’ Meeting in Schulpforta in July 1922, Barth offered the following remarks:

Speaking at a Ministers’ Meeting in Schulpforta in July 1922, Barth offered the following remarks: