There’s a scene in Terrence Malick’s film Thin Red Line where a young soldier gives voice to a series of imponderable and ancient questions about meaning, about the ‘thin red line’ between life and suffering and death. In what is essentially a prayer, he asks:

This great evil. Where does it come from? How’d it steal into the world? What seed, what root did it grow from? Who’s doing this? Who’s killing us? Robbing us of life and light. Mocking us with the sight of what we might have known. Does our ruin benefit the earth? Does it help the grass to grow or the sun to shine? Is this darkness in you, too? Have you passed through this night?

These questions haunt human history and seem to give lie to the claim that the earth is good, that behind and before history, that behind and before our life, that behind and before our agonising questions, stands one whom the NT calls ‘love’. It is little wonder then that we ask ‘why’ – why, if the Creator is good and powerful and loving, are there tsunamis and earthquakes? Why, if the Creator is on the side of life, will 29% of New Zealanders die of cancer? Why, if the Creator is the one who brings shalom, do 20% of us suffer from anxiety and mood disorders on a daily basis? Why, if the Creator is a father who knows how to give good gifts to his children, are there 925 million people who share life with us on this planet hungry? Why, if Jesus is the bringer of a new thing, is the world so unchanged? If this is how a good God governs the world, and because our cry for answers seems to illicit no response, it is little wonder that we lose hope and we begin to wonder not only do I have a future, but also does creation itself have a future, and even does God have a future.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell spoke for not a few when he wrote:

I can imagine a sardonic demon producing us for his amusement, but I cannot attribute to a Being who is wise, beneficent, and omnipotent the terrible weight of cruelty, suffering, and ironic degradation of what is best, that has marred the history of Man in increasing measure as he has become more master of his fate.[1]

And so we come to the ancient Book of Job, a book which begins with these words:

There was once a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job. That man was blameless and upright, one who feared God and turned away from evil. There were born to him seven sons and three daughters. He had seven thousand sheep, three thousand camels, five hundred yoke of oxen, five hundred donkeys, and very many servants … (Job 1.1–3)

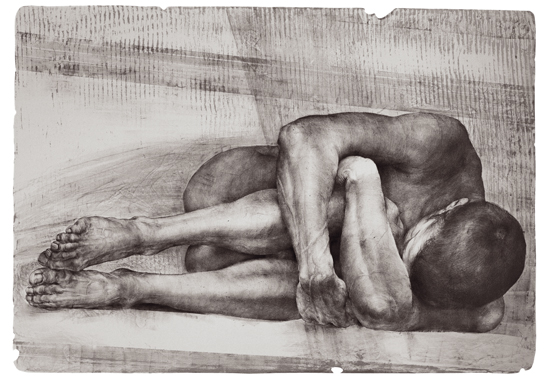

Such fertility represents signs, in the Semitic world, of a family under the blessing of God. But not for long. Soon Job is robbed of every iota of financial prosperity and security that was his familiar lot, his children all die in a tragic accident, his livestock are stolen from him, he himself falls victim to a painful and disfiguring chronic disease, and then even his wife turns against him with the words, ‘Curse God and die’. And, perhaps most terrible of all, the book suggests that all of these things happen by God’s permission.

And then for the next 36 or so chapters, Job’s so-called friends – the would-be theologians – instead of waiting with Job for God to speak, they rush in to defend God with their moronic and ignorant theological speculations and they try to convince Job that he must have done something wrong to bring about this state of affairs. On the other hand, Job, for his part, rather than engage in philosophical speculation about the meaning of suffering – as if there might even be such meaning – turns to address God; first by cursing the day of his birth, and then later by challenging God to a day in court where the injustices of his life might be evaluated before someone or something manifestly less prejudicial than God. And what strikes me about this litany of complaints is that rather than jump onto some ancient equivalent of an online social networking site and whinge to others about his loss, Job turns to prayer. He is completely in the dark as to the reason for his suffering, but again and again and again he commits his cause to God. Consider these words from chapter 13:

See, he will kill me; I have no hope; but I will defend my ways to his face … Why do you hide your face, and count me as your enemy? Will you frighten a windblown leaf and pursue dry chaff? For you write bitter things against me, and make me reap the iniquities of my youth. You put my feet in the stocks, and watch all my paths; you set a bound to the soles of my feet. One wastes away like a rotten thing, like a garment that is moth-eaten. (13.15, 24–28)

This theme is further developed in chapter 14 where we are invited to ask, ‘In the midst of such tragedy, in the midst of our agonies, in the midst of living with our demons and black dogs, in the midst of so many unanswered questions, “Can we hope?” And, if so, what might possibly be the basis of such hope?’

The chapter begins with a sober description of the experience of human life:

A mortal, born of woman, few of days and full of trouble, comes up like a flower and withers, flees like a shadow and does not last. Do you fix your eyes on such a one? Do you bring me into judgment with you? Who can bring a clean thing out of an unclean? No one can. (vv. 1–4)

And then we hear something of Job’s bitterness towards God as if he is addressing the schoolyard bully:

Since their days are determined, and the number of their months is known to you, and you have appointed the bounds that they cannot pass, look away from them, and desist, that they may enjoy, like laborers, their days. (vv. 5–6)

In other words, ‘God, since you have already planned all our days, and even our deaths, why can’t you just leave us alone to live out whatever life we have been given, because it seems like every time you come near, my life just falls apart’.

According to Job, our fate is hopeless. We all die, and when we breathe our last, we lie down and never get up. In fact, Job says that even the trees have more hope than we do:

For there is hope for a tree, if it is cut down, that it will sprout again, and that its shoots will not cease. Though its root grows old in the earth, and its stump dies in the ground, yet at the scent of water it will bud and put forth branches like a young plant. But mortals die, and are laid low; humans expire, and where are they? As waters fail from a lake, and a river wastes away and dries up, so mortals lie down and do not rise again; until the heavens are no more, they will not awake or be roused out of their sleep. (vv. 7–12)

Now most scholars argue that the real turning point of this chapter is in v. 14 when Job asks the question: ‘If mortals die, will they live again?’ (v. 14). And many commentators highlight how Job’s question here whispers that something else might be possible; that despite all evidence to the contrary, some crack might appear in an otherwise closed door and let in some fresh air, some crack which suggests that despite every appearance we are creatures not of chance but of One who has orientated us towards a hopeful future. It’s a fine way to read the passage, though I wonder if it too quickly closes our ears to something else that is important here.

For it may be that the real turning point in this passage actually lies on either side of these words – in v. 13 and in the second half of v. 14 – where Job speaks of both remembering and of waiting:

O that you would hide me in Sheol (i.e., in the underworld, the hiding place from God’s scrutiny and anger), that you would conceal me until your wrath is past, that you would appoint me a set time, and remember me! … All the days of my service I would wait until my release should come.

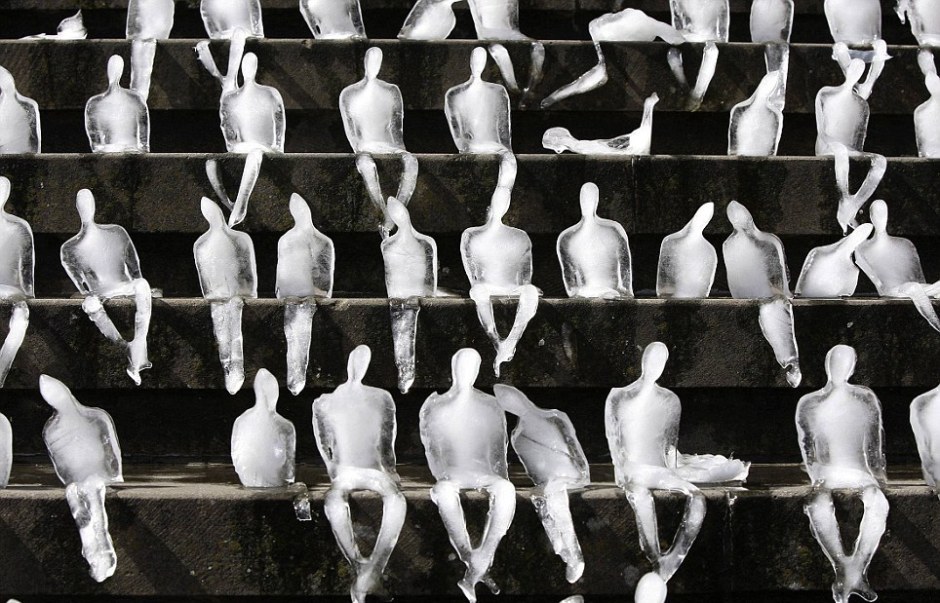

The language of remembrance and of waiting is, of course, familiar language around the church. It’s the language that we hear not only around Advent, but also during Lent and during Easter, and during so-called Ordinary Time. But if there’s one day in the church’s calendar when the language of remembrance and of waiting is most intense it is on the quietest day of the Christian year – Holy Saturday. And the story of Job is the story of one faithful person’s experience of Holy Saturday, just as the book of Lamentations recalls on a corporate level the whole community’s journey through its own experience of God abandonment. And Holy Saturday reminds us that there’s waiting and then there’s waiting. For whereas the quality of Advent waiting brims with expectation and preparation for hope to ring and joy to arrive like having warm bread in the oven, the air of Holy Saturday reeks of stale smoke, as though something was burned the day before. The silence of this day is not like the silence of restoration and anticipation and peace. The silence of Holy Saturday sounds more like the buzz of a lonely streetlight on a dark deserted road in the middle of nowhere. It’s the silence of paralysing shock. It’s the silence of shattered hopes. It’s the kind of silence when nothing feels safe or dependable anymore.

The waiting of Job and the waiting of Holy Saturday are like waiting for a teenage son or daughter who has missed a midnight curfew to come home, or like waiting for the surgeon to emerge from the hospital operating room, or like waiting for the phone to ring with a report of biopsy results. Like Job’s questions, Holy Saturday is a day of suspense. It is the boundary marker between the undeniable and the inconceivable. It is, in the words of one theologian, what ‘appears to be a no-man’s land, an anonymous, counterfeit moment in the gospel story, which can boast no identity for itself, claim no meaning, and reflect only what light it can borrow from its predecessor and its sequel’.[2] And it is the space all too familiar to those of us who grieve the loss of one whom death has claimed prematurely. It is the space all too familiar to those of us who live with the burden of unreconciled relationships. It is the space all too familiar to those of us who live with the anxiety of not knowing whether or not we will always be recognisable to our loved ones.

And I want to suggest that what holds that space together – what fills the boundary between death and life, between despair and hope, between love experienced and love unimaginable – is the divine memory. It is God’s memory of us which makes it possible for us to neither abandon our sorrow nor to surrender the horizon of hope. It is God’s memory which places a boundary to our hopelessness and our dislocation. It is the memory of the God who remembered Rachel and filled her barren womb (Gen 30.22). It is the memory of the God who heard Israel groaning under the burden of cruel slavery and remembered an ancient promise to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It is the memory of the God who heard the desperate cry of a frightened thief and made a promise to accompany him even beyond death. And it strikes me that the dead Jesus is resurrected too precisely because he is not forgotten by the Father and the Spirit.

Job knows that one day all who know him will pass away and that his achievements will be long abandoned. He knows the futility of trusting in what will only return to dust. He knows the futility of trusting in those shrines of remembrance that we erect in our lives and in our churches and in our communities. But as fragile as he is, he is not finally without hope, and his hope is not that he will be faithful enough to remember God but that God is faithful to remember him, that he will be kept alive only by God’s memory of him. Job’s hope is that despite all appearances, God’s memory outlasts this creation which is passing away. This is great news for those of us who have ‘lost’ their memory, and for those of us who live with those who have ‘lost’ their memory – for it announces that our dignity and hope and humanity are not to be found finally in our ability to remember and to love but rather in the promise of one who both remembers and loves and who does so beyond the boundaries that death itself would seek to erect.[3]

When pain torments our body; when unwelcome fantasies invade our sleep; when friends unite to condemn or to abandon us; when death hovers on our doorstep – then, it is not finally a kind word or a new resolve that we need but rather an encounter with the God who remembers us, who remembers that we are dust; who is, in the words of Psalm 8, ‘mindful’ of us; who remembers that our history is not something that can be discarded willy-nilly, and who, in Jesus Christ, enters into the boundary of our dislocation and into the emptiness of our long-abandoned memories and who publicises to and for us that we are not forgotten. The reason for our hope is that we are remembered in life; we are remembered when disaster engulfs robbing life of joy and peace; and we are remembered in our graves. The reason for our hope is that we are remembered by God when all other memories have dried up, when all has passed away and the creation itself undone, when (as in v. 19) the waters wear away the stones and the torrents wash away the soil of the earth and all human hopes are extinguished.

And, finally, in the crucified God, we hope together with those who do not share our hopes, and with those whose hopes for this life remain unfulfilled, and with those who are disappointed and indifferent, and with those who despair of life itself, and with those who have been the enemies of life, and with those who for whatever reason have abandoned all hope. In and with Christ, we hope and we remember them before God. In the crucified God, we hope together with the God who remembers us and who, in remembering us, is our hopeful end. Amen.

[1] Bertrand Russell, Last Philosophical Testament: 1943–68 (ed. John G. Slater and Peter Köllner; The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, Volume 2; London: Routledge, 1997), 87.

[2] Alan E. Lewis, Between Cross and Resurrection: A Theology of Holy Saturday (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2001), 2–3.

[3] No wonder that John Calvin once said that ‘there is nothing [human beings] ought fear more than to be forgotten by God’. John Calvin, Sermons from Job (trans. Leroy Nixon; Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1952), 78.

Sally Lloyd-Jones and Sam Shammas, The Jesus Storybook Bible Curriculum Kit (Grand Rapids: Zondervan; 2012) – a review

Sally Lloyd-Jones and Sam Shammas, The Jesus Storybook Bible Curriculum Kit (Grand Rapids: Zondervan; 2012) – a review