Last spring, one of the graduating M.Div. seniors at Austin Seminary asked us professors for a list of books he should read “sometime in his life.” A heartening request, but it got even better. In the last few months, John has made it clear that he does not understand “sometime” to mean an ever-receding future in which he will (he hopes) have the time to read. On the contrary, John seems to think that “sometime” began the day after graduation. Last week, in fact, I received an e-mail which revealed that John is on schedule to complete five classics—by à Kempis, Bonhoeffer, Dillard, H. R. Niebuhr, and Moltmann—by this December. Inspiring, isn’t it? But here’s the catch: he has not yet taken a call. Will he be able to keep on reading, once he becomes a pastor?

Last spring, one of the graduating M.Div. seniors at Austin Seminary asked us professors for a list of books he should read “sometime in his life.” A heartening request, but it got even better. In the last few months, John has made it clear that he does not understand “sometime” to mean an ever-receding future in which he will (he hopes) have the time to read. On the contrary, John seems to think that “sometime” began the day after graduation. Last week, in fact, I received an e-mail which revealed that John is on schedule to complete five classics—by à Kempis, Bonhoeffer, Dillard, H. R. Niebuhr, and Moltmann—by this December. Inspiring, isn’t it? But here’s the catch: he has not yet taken a call. Will he be able to keep on reading, once he becomes a pastor?

Pastors commonly lament that they aren’t able to keep up with the biblical languages. But in my conversations with pastors, frustration with keeping up with the theological literature is also conveyed. Frequent comments include: “There are just so many books out there—how do I know what to read?” “Why don’t theologians write shorter books? When I do have time to work through one, I feel like the author could have gotten to the main point a lot sooner,” and “Why don’t theologians ever write books for pastors?” My sense is that pastors yearn to participate in the wider theological conversation, but do not want to have to fight their way in. Any of us could generate a dozen ideas for how pastors can be helped with their theological reading. Seminaries could provide bibliographies—and, possibly, “book reports” on specific theological works—on-line. Pastors could form reading groups that meet weekly to discuss and encourage one another. Churches could include a weekly “reading day” in pastors’ job descriptions (try not to laugh).

Theology professors might help pastors strategize on how to read particular theologians, given their different emphases, styles, and contexts. For example, a professor might advise: (1) Be sure to keep a pocket dictionary of philosophical terms on your desk while reading Tillich; or (2) Don’t worry, when reading Barth, if your mind wanders, here and there. Let his words wash over you like a piece of music by Mozart . . . eventually, he’ll come back to whatever point you missed; or (3) Don’t immediately assume Gutiérrez is wrong, just because you don’t resonate with his argument. Allow him to let you “see” what theology looks like from a Latin American context.

While any of these strategies might be helpful in managing symptoms of the problem, I wonder if there is not also a need to address what underlies feelings of being overwhelmed, concerns about having too little time, and fears about wasting time on words that don’t have immediate application to the “real world” work of ministry. As helpful as “how-to” advice can be, I have come to believe that the fundamental problem pastors have with reading theology is not a dearth of information regarding what and how to read, but an absence of the conviction that the theological conversation is their conversation.

In the remainder of this brief essay I will propose four points for reflecting on “how to read a theology book” that focus less on the doing of the reading and more on our being as readers. Instead of pushing you to “just do it” (read theology), I reflect on what it means to “really be it” (a reader of theology). The theology of the Reformation, in contrast to our cultural wisdom, teaches us that we don’t create ourselves by doing. Nor does what we do (or not do) always reveal who we are, for we are sinful. Rather, what we do is to proceed from who we are: beloved children of God; brothers and sisters of Christ.

With this in mind, I suggest that the fundamental strategy for reading a theology book is to engage it as those who: remember who we are; revel in the richness of our inheritance; converse with our fellow heirs; and create with Christ as partners in the ministry of reconciliation. Let me explore the four facets of this strategy in greater detail.

REMEMBER.

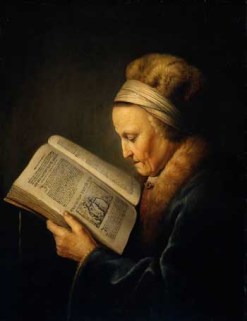

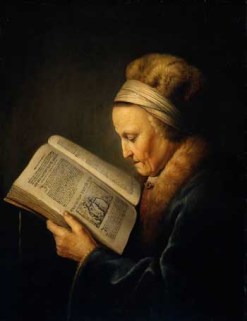

“TO SIT ALONE IN THE LAMPLIGHT WITH A BOOK SPREAD OUT BEFORE

YOU, AND HOLD INTIMATE CONVERSE WITH [PEOPLE] OF UNSEEN GENERATIONS—

SUCH IS A PLEASURE BEYOND COMPARE.”—Kenko Yoshida

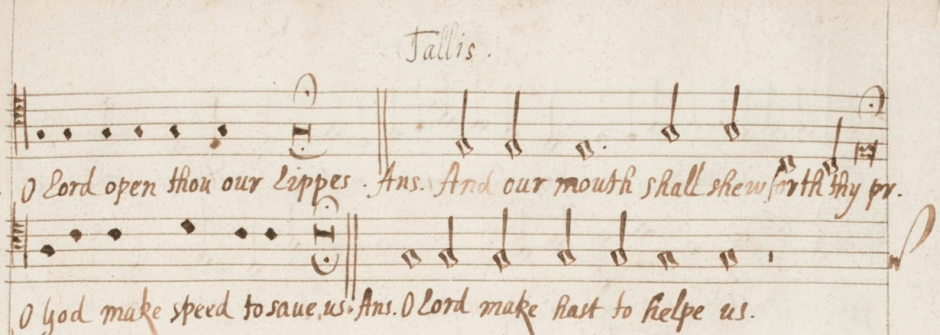

Week after week, pastors remind members of their congregations of who they are. “You are children of God,” we tell them. “You are joined, at this Table, with Christians all around the world—from every time and place.”

But how do these affirmations come into play—practically speaking—when we pick up a theology book and steal an hour to read? If we think of reading theology as something we do outside of community, as a kind of hunting for provisions to bring “home” to our congregations, it is no wonder we’re frustrated when the hunt seems unsuccessful! In actuality, to spend an afternoon with a text like Calvin’s Institutes is not to close ourselves off from the community in order to “study.” Rather, it is to be intentional about creating a space to develop an intimate relationship with a fellow seeker of understanding, a crucial member of the community of faith. As we read, we hold in our hands a tangible link to brothers and sisters in Christ from “unseen generations.” Like the bread that joins us to those who partake in different times and places, so the theology book has a sacramental quality—participating in a reality larger than the sum of the meanings of the words inside.

I wonder if pastors neglect their theological reading because, on some level, they understand it to be in tension with their calling to be with people. If reading a theology book means leaving the community behind or sitting in the proverbial “ivory tower,” it’s no wonder that ministers—and their congregations—are hesitant to make it a priority. But what if we were convinced that to read theology was to sit in the midst of the community, inviting the saints separated from us by time and space to enter into the circle with us? When we read as rememberers of who we are in relationship to others, our communal life is enriched by the physically absent who are really made present.

REVEL.

“BOOKS, BOOKS, BOOKS . . . LIKE SOME SMALL NIMBLE MOUSE BETWEEN

THE RIBS OF A MASTODON, I NIBBLED HERE AND THERE AT THIS OR

THAT BOX . . . THE FIRST BOOK FIRST. AND HOW I FELT IT BEAT UNDER

MY PILLOW, IN THE MORNING’S DARK. AN HOUR BEFORE THE SUN

WOULD LET ME READ! MY BOOKS!”—Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Theological books abound, it seems. Many pastors, like Browning, have inherited box after box of dusty old books. But how many of us have heard them beating under our pillows?

We might approach our theology books with dread, rather than joy-full anticipation, because we are afraid they might defeat us in our struggle to read. With no intention to “nibble here and there”—but only to succeed in our mission to conquer—we are back on the hunt. And who can fault us, in our competitive context, for setting our sights high? For wanting to master the material?

Recognizing that it is impossible to read every word of every book, students sometimes ask me to help them formulate an attack plan. Perhaps seminaries should offer courses in speed reading, some have suggested. That way, graduates would have some hope of keeping up once they leave seminary and take a church.

Drawn by Browning’s curious and playful spirit, I suggest that the “divide and conquer” approach to reading theology should be resisted. I wonder, instead, if “remembering” who we are as members of the Christian community can inspire us to approach our books with a spirit of revelry—knowing that the point isn’t to learn it all; loving how much theology there is; immersing ourselves in it. When we pick up a theology book, we might imagine ourselves sitting in a room full of the treasures that are our inheritance, basking in the wonder that we can’t begin to count how much there is. When we engage in our theological reading, we might envision ourselves encircled by colorful friends we can spend a lifetime getting to know. The goal of our reading, then, is not to master, control, or conquer, pleading for understanding whenever we haven’t done what we know we should do. Rather, it is to live into our identity as members of the body of Christ: to enter into relationship; to revel in the possibilities; to open ourselves up to the great cloud of witnesses that surrounds us; to hear the pulse.

CONVERSE.

“READING FURNISHES THE MIND ONLY WITH MATERIALS OF

KNOWLEDGE;IT IS THINKING THAT MAKES WHAT WE READ OURS.”—John Locke

As rememberers who sit in the center of the circle and revel in the riches that surround us, one of our greatest joys is to enter into the conversation. To read theology books is not like entering a museum, where we might work our way around from display to display without feeling the need to announce our presence or opinions. On the contrary, if reading a theology book is about developing a relationship with a brother or sister in Christ, our active participation is required and desired. When we read a theology book, we are being called upon to make a thoughtful contribution to the circle itself.

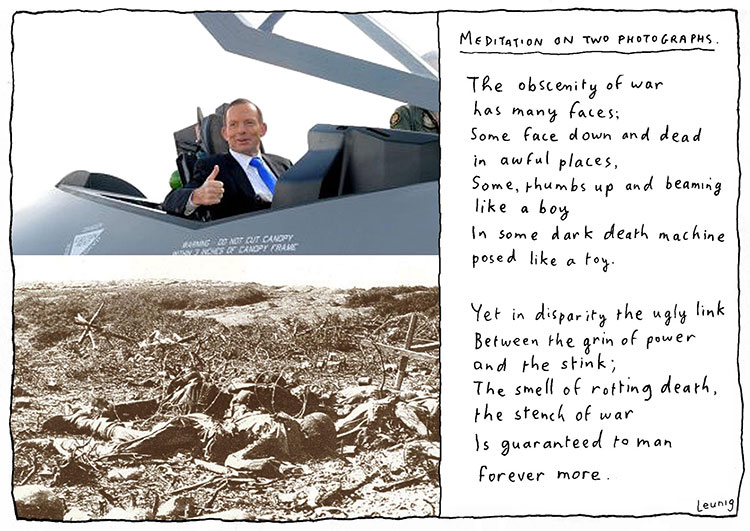

Eager to engage the circle of witnesses who surround us, we should avoid reading theology books Siskel-and-Ebert style. The “thinking” which Locke advocates would shrivel from self-centered declarations about whether we agree or disagree with the author, or whether the book “works” for us. To offer a simple “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” in response to our theological reading is, again, to fall into a “hunt and conquer” rather than a “remember and revel” mentality.

Remembering who we are in relation to the authors of the theology books who surround us, we make theological ideas our own in the context of conversation. “Talking with” our theology books, then, requires committed attempts to understand what the other is saying, even when we disagree. It involves asking questions (OK . . . a bit difficult to do when you are reading a book and not talking to a “live” person . . . but try writing them in the margins and see if the author addresses them later). It respects the other enough to argue, rather than conveniently dismissing.

As we think about what we are reading, conversing with the witnesses who surround us, we will find that we are being shaped and molded in our Christian convictions. We begin, then, to read theology not only with the hope that we will find ideas for our next sermon or lecture series, but with the expectation that we will, indeed, be changed.

CREATE.

“YOU ARE THE SAME TODAY THAT YOU ARE GOING TO BE IN FIVE YEARS

FROM NOW EXCEPT FOR TWO THINGS: THE PEOPLE WITH WHOM YOU

ASSOCIATE AND THE BOOKS YOU READ.”—Charles Jones

We read theology as creatures called to participate in God’s work of creation; as partners in the ministry of reconciliation and as ministers charged to tend the sheep of God.

But the charge to join in God’s ongoing creative work comes with a reminder: We are creators not as God is Creator, for we create only as creatures. Our creative ministerial acts flow not from omnipotence or a never-ending store of Wisdom, but from the reality of our own ongoing creation. The replenishing of our resources that we seek when reading theology will not translate into effective ministry unless we ourselves are replenished. For theology books to get our creative theological juices flowing, we have to be created by them. And if we ask the reasonable question—how can we be created by a mere book?—it’s time to go back to remembering. Theology books are not only books, but vehicles through which we enter into relationship with the communion of saints. Theology books are not to be attacked, and finished, and evaluated, but participated in, and conversed with, and nibbled again and again.

When we read theology in this way, our reading becomes less a matter of “something I work into my schedule because it’s important” and more a reflection of who we are. Reading theology doesn’t make us theologians; we read theology because we are theologians. As those who are called to speak words about God, how can we do otherwise than remember our relationship to the saints, revel in our inheritance, converse openly with one another, and create out of our ongoing re-creation in Christ? However we go about the logistics of our reading, let us seek to live into the truth that theology books are God’s open-ended invitation to join in communion.