- Keith Thomas laments the state of the modern university, in Universities under Attack.

- Charles Simic on Serenity.

- Alan Hollinghurst and Jeffrey Eugenides on the art of fiction.

- The Changi POW artwork of Des Bettany is finally online – a beautiful project. Speaking of war art, check out Macy Halford’s piece on An Artist’s War.

- Chad Marshall reviews Mark S. Gignilliat’s Karl Barth and the Fifth Gospel: Barth’s Theological Exegesis of Isaiah.

- Michiko Kakutani reviews Robert Hughes’s Rome: A Cultural, Visual, and Personal History.

- Jarrod M. Longbons’s interview with Tracey Rowland on Pope Benedict XVI.

- The gospel according to Stephen Fry; and Fry on London.

- The Centre for Theology and Ministry (Uniting Church in Australia) is seeking a new Professor of Systematic Theology.

- Robert Fisk on bankers as the dictators of the West.

- Ben Myers looks through an icon of theophany.

- Rick Floyd reminds me of that old Bing Crosby cassette I probably still have laying around in a box somewhere.

- A Rowan Williams lecture on The Future of Interfaith Dialogue.

- Crispin Blunt’s lecture on Restorative Justice.

- Steve Holmes reviews Scot McKnight’s Junia Is Not Alone.

- Finally, I’m still relishing John Updike’s Higher Gossip.

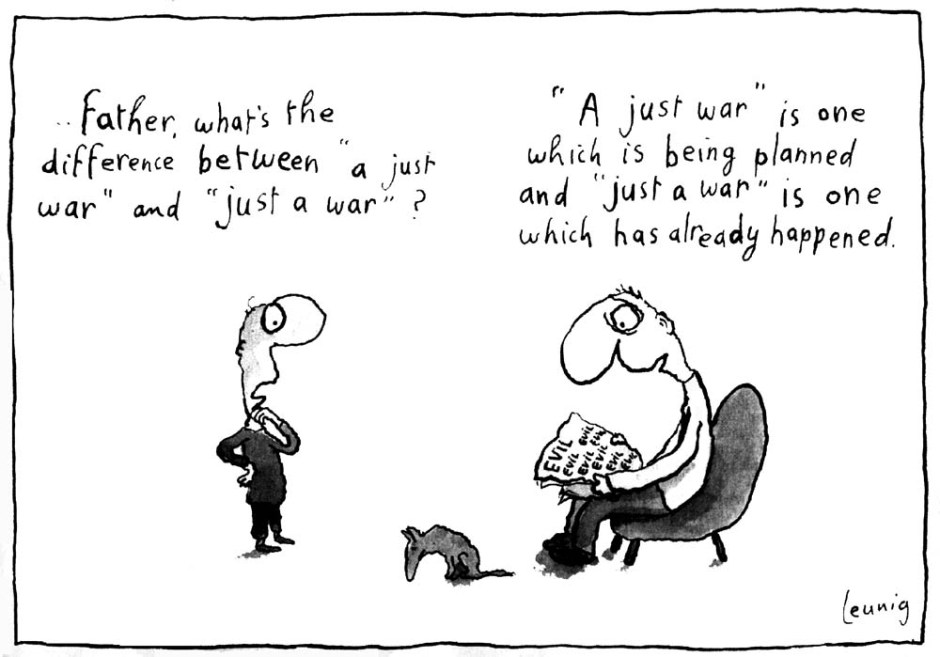

War

On blood and guts, violence and death

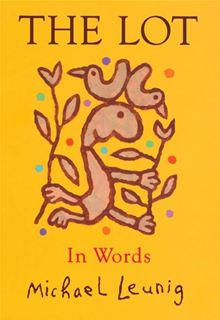

I’ve been enjoying this delightful collection of short essays by the Melbourne-born poet, artist and cultural commentator Michael Leunig. Here’s a snippet from his essay ‘Blood and Guts, Violence and Death’:

I’ve been enjoying this delightful collection of short essays by the Melbourne-born poet, artist and cultural commentator Michael Leunig. Here’s a snippet from his essay ‘Blood and Guts, Violence and Death’:

“No nation can go to war without a sufficient reserve of hatred, cruelty and bloodlust politely concealed in its general population, and if our so-called Western democracies wanted their ‘war against terror’, then let them now at least see the graphic details of war’s sickening and hideous consequences.

The curse is, however, that it’s the children who are most defiled and blighted by such frightening imagery – and they had no part in it.

My years in the abattoir taught me that society denies its bloodlust and cruelty and imagines that such impulses appropriately belong to prehistoric barbarians, or ‘rough and uncouth men’. But I believe we now have the unique modern cruelty of the refined and educated Western man, the respected gentleman in the fine suit who has never much dirtied his hands or killed a living creature, never meditated upon a rotting corpse and never had his consciousness infected with the messy organic substances of violent death – yet who can sign with an elegant golden pen the document that unleashes the cowardly invasion and who can then go out to dine on claret and lamb cutlets.

The likes of these men abound in the halls of academia, the boardrooms and corridors of power, and the chicken-coop workstations of the media, where they have clamoured for war, for all sorts of ungodly and unfathomable reasons, without really knowing in their bones how it works – the business of violence and blood and guts.

They are primally inexperienced, unconnected and unwise. Their flesh has not been seared. Their repressed death fascination and sly cruelty has not yet been transformed into reverence and understanding by initiation into things carnal and spiritual, by the actual sights and sounds of splattering blood and crunching bone, and the pitiful flailing and wailing of violent death – the very thing they would unleash upon others. Just one sordid street-fight or one helpless minute of aerial bombardment might redeem them. They lack the humbling erudition of the slaughterman, the paramedic and, no doubt, the soldier who has really been a soldier.

I dare say there’s something foul, creepy and disgraceful emerging in the character of corporate and political leadership in ‘Western civilisation’, and I sense it’s substantially the result of an insipid masculinity problem.

The insatiable need for heartless power and ruthless control is the telltale sign of an uninitiated man – the most irresponsible, incompetent and destructive force on earth.”

– Michael Leunig, The Lot: In Words (Camberwell: Penguin, 2008), 50–2.

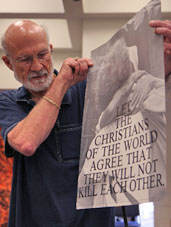

Hauerwas on the Church and the abolition of war

In Hauerwas’ latest piece, ‘Ten Years and Counting: The Church and the Abolition of War’, we hear, near the eve of 9/11, themes long-echoed by Yoder’s most prolific publisher:

In Hauerwas’ latest piece, ‘Ten Years and Counting: The Church and the Abolition of War’, we hear, near the eve of 9/11, themes long-echoed by Yoder’s most prolific publisher:

‘I want to convince Christians that war has been abolished. The grammar of that sentence is very important. The past tense is very deliberate. I do not want to convince Christians to work for the abolition of war, but rather I want us to live recognizing that in the cross of Christ war has been abolished.

So I am not asking Christians to work to create a world free of war. The world has already been saved from war. The question is how Christians can and should live in a world of war as a people who believe that war has been abolished’.

You can read the rest here.

I’ve also posted some resources on pacifism and war here.

‘How To Kill’, by Keith Douglas

Under the parabola of a ball,

Under the parabola of a ball,

a child turning into a man,

I looked into the air too long.

The ball fell in my hand, it sang

in the closed fist: Open Open

Behold a gift designed to kill.

Now in my dial of glass appears

the soldier who is going to die.

He smiles, and moves about in ways

his mother knows, habits of his.

The wires touch his face: I cry

NOW. Death, like a familiar, hears

And look, has made a man of dust

of a man of flesh. This sorcery

I do. Being damned, I am amused

to see the centre of love diffused

and the wave of love travel into vacancy.

How easy it is to make a ghost.

The weightless mosquito touches

her tiny shadow on the stone,

and with how like, how infinite

a lightness, man and shadow meet.

They fuse. A shadow is a man

when the mosquito death approaches.

– Keith Douglas, ‘How To Kill’ in Keith Douglas: The Complete Poems (ed. Desmond Graham; London: Faber & Faber, 2000), 119.

Writing off Yoder

The latest edition of One the Road, the journal of the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand, includes a helpful piece by Michael Buttrey titled ‘12 ways to prematurely write off Yoder: Some common misconceptions about Yoder’s ‘Neo-Anabaptist’ vision’. Buttrey identifies the twelve ‘misconceptions’ as:

The latest edition of One the Road, the journal of the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand, includes a helpful piece by Michael Buttrey titled ‘12 ways to prematurely write off Yoder: Some common misconceptions about Yoder’s ‘Neo-Anabaptist’ vision’. Buttrey identifies the twelve ‘misconceptions’ as:

1. Yoder believes Constantine corrupted the church.

2. Yoder thinks that there was no salt or light in the medieval church.

3. Yoder hates Luther, Calvin and the other magisterial Reformers.

4. Yoder has a low view of God’s sovereignty over history. Or:

5. He idolizes the early church.

6. Yoder inappropriately sees Jesus’ earthly life as normative.

7. Yoder fails to deal with the Old Testament, especially the wars of Joshua.

8. Yoder’s pacifism inhibits any effective witness to the state, especially regarding war.

9. Even for Christians, Yoder’s pacifism is impossible, or at least irresponsible.

10. Yoder advocates separation from the world that ‘God so loved.’ And:

11. Isn’t Yoder a ‘fideistic sectarian tribalist’ like Stanley Hauerwas?

Here, Buttrey writes:

These common accusations seriously misunderstand Yoder.

First, Yoder’s context was one where he was urging traditionally quietist Anabaptists to realize they had a social ethic and witness to society, while simultaneously calling activist Christians to realize they need not abandon the gospel and take up the methods of the world in their impatience to get things done. Ironically, Yoder has often been taken more seriously by theologians and political philosophers outside his tradition – such as Stanley Hauerwas and Romand Coles – than those on the ‘inside.’

Second, Yoder has no desire to divide the church further. Indeed, in “The Kingdom As Social Ethic” he deeply objects to the labelling of radically obedient groups as sectarian, for they had no intentions of separating themselves:

[Such groups] have called upon all Christians to return to the ethic to which they themselves were called. They did not agree that their position was only for heroes, or only possible for those who would withdraw from wider society. They did not agree to separate themselves as more righteous from the church at large. (85)

Third, Yoder is fundamentally not interested in withdrawal or separation from society. In “The Paradigmatic Public Role of God’s People,” Yoder agrees with Karl Barth that ‘what believers are called to is no different from what all humanity is called to. … To confess that Jesus Christ is Lord makes it inconceivable that there should be any realm where his writ would not run.’ (25) Of course, those who seriously see Christ’s commands as normative for all tend to be called fideists or theocrats. Yoder is neither.

Yoder is not a fideist because, unlike most realists, he sees the gospel as having a truly universal appeal. Christian realists typically assume that the gospel is inaccessible and incomprehensible to all other groups, and so it is necessary to use a neutral, ‘public’ language to oblige non-Christians ‘to assent to our views on other grounds than that they are our views.’ (16–7) Indeed, it is not Yoder but his critics who tend to think that their faith is fundamentally irrational and its public demands must be set aside for that reason. This reverse fideism is not surprising, however, given how modern liberal democracies understand religious groups and language.

Further, Yoder is not a theocrat, because he does not call for the violent imposition of the gospel, which would be an oxymoron. Rather, the challenge for the church is to purify its witness so ‘the world can perceive it to be good news without having to learn a foreign language.’ (24) Christ’s universal lordship obliges the church to make great demands of the world, but by definition, the gospel witness is a process of public dialogue, not coercion.

In short, the best word for Yoder’s understanding of the church’s witness to society is that of model. Consider some of these potential imperatives for civil society Yoder derives theologically in that same essay:

- egalitarianism, not because it is self-evident (history suggests that it is clearly not!) but because baptism into one body breaks down ethnic and cultural barriers;

- forgiveness as commanded by Christ (he agrees with Hannah Arendt that a religious origin and articulation for forgiveness is no reason to discount it in secular contexts);

- radical sharing and hospitality, even voluntary socialism, as implied in the Eucharist; and

- open public meetings and dialogue, as Paul instructed the Corinthians.

This sketch is almost a political “platform,” and hardly separatist. But for Christians with typical approaches to politics, Yoder’s call for the church to be where God’s vision for society is first implemented and practiced is an enormous stumbling block. It is yet another irony that realists are so often closet quietists: they see the only choice as being between transforming society and letting it go its own way. Yoder, however, asks us to obey Christ even if no one else is interested – although he trusts that the Kingdom will advance if the word of God is faithfully witnessed and embodied amid the powers and principalities of the world.

12. Yoder and Stanley Hauerwas are the same.

You can read the full piece here.

Hauerwas on War, Sacrifice and the Alternative to the Sacrifices of War

The ABC’s outstanding Religion and Ethics site has recently posted a stirring three-part reflection on war by Stanley Hauerwas:

- The Sacrifices of War

- War as the Sacrifice of the Refusal to Kill

- The Sacrifice of Christ and the Sacrifices of War

Here are some tasters:

- ‘I think the language of sacrifice is particularly important for societies like the United States in which war remains our most determinative common experience, because states like the United States depend on the story of our wars for our ability to narrate our history as a unified story’.

- ‘I think it is a mistake to focus – as we most often do – only on the sacrifice of life that war requires. War also requires that we sacrifice our normal unwillingness to kill. It may seem odd to call the sacrifice of our unwillingness to kill “a sacrifice,” but I will argue that this sacrifice often renders the lives of those who make it unintelligible. The sacrifice of our unwillingness to kill is but the dark side of the willingness in war to be killed. Of course I am not suggesting that every person who has killed in war suffers from having killed. But I do believe that those who have killed without the killing troubling their lives should not have been in the business of killing in the first place … Killing creates a world of silence isolating those who have killed’.

‘Awarding of medals becomes particularly important. Medals gesture to the soldier that what he did was right and the community for which he fought is grateful. Medals mark that his community of sane and normal people, people who do not normally kill, welcome him back into “normality.” [Lt Col Dave] Grossman calls attention to Richard Gabriel’s observation that “primitive societies” often require soldiers to perform purification rights before letting them rejoin the community. Such rites often involve washing or other forms of cleaning. Gabriel suggest the long voyage home on troop ships in World War II served to give soldiers time to tell to one another their stories and to receive support from one another. This process was reinforced by their being welcomed home by parades and other forms of celebration. Yet soldiers returning from Vietnam were flown home often within days and sometimes hours of their last combat. There were no fellow soldiers to greet them. There was no one to convince them of their own sanity. Unable to purge their guilt or to be assured they had acted rightly, they turned their emotions inward’.

‘Awarding of medals becomes particularly important. Medals gesture to the soldier that what he did was right and the community for which he fought is grateful. Medals mark that his community of sane and normal people, people who do not normally kill, welcome him back into “normality.” [Lt Col Dave] Grossman calls attention to Richard Gabriel’s observation that “primitive societies” often require soldiers to perform purification rights before letting them rejoin the community. Such rites often involve washing or other forms of cleaning. Gabriel suggest the long voyage home on troop ships in World War II served to give soldiers time to tell to one another their stories and to receive support from one another. This process was reinforced by their being welcomed home by parades and other forms of celebration. Yet soldiers returning from Vietnam were flown home often within days and sometimes hours of their last combat. There were no fellow soldiers to greet them. There was no one to convince them of their own sanity. Unable to purge their guilt or to be assured they had acted rightly, they turned their emotions inward’.- ‘Killing shatters speech, ends communication, isolating us into different worlds whose difference we cannot even acknowledge. No sacrifice is more dramatic than the sacrifice asked of those sent to war, that is, the sacrifice of their unwillingness to kill. Even more cruelly, we expect those who have killed to return to “normality”’.

- Hauerwas also cites from Carolyn Marvin’s and David Ingle’s book Blood Sacrifice and the Nation: Totem Rituals and the American Flag: ‘In the religiously plural society of the United States, sectarian faith is optional for citizens, as everyone knows. Americans have rarely bled, sacrificed or died for Christianity or any other sectarian faith. Americans have often bled, sacrificed and died for their country. This fact is an important clue to its religious power. Though denominations are permitted to exist in the United States, they are not permitted to kill, for their beliefs are not officially true. What is really true in any society is what is worth killing for, and what citizens may be compelled to sacrifice their lives for’. To which Hauerwas comments: ‘This is a sobering judgment, but one that cannot be ignored if Christians are to speak truthfully to ourselves and our neighbours about war. I think, however, Christians must insist that what is true is not what a society thinks is worth killing for, but rather that for which they think it worth dying. Indeed, I sometimes think that Christians became such energetic killers because we were first so willing to die rather than betray our faith. Yet the value of Marvin’s and Ingle’s claim that truth is to be found in that for which you are willing to kill is how it helps us see that the Christian alternative to war is not to have a more adequate “ethic” for conducting war. No, the Christian alternative to war is worship … The sacrifices of war are undeniable. But in the cross of Christ, the Father has forever ended our attempts to sacrifice to God in terms set by the city of man. We (that is, we Christians) have now been incorporated into Christ’s sacrifice for the world so that the world no longer needs to make sacrifices for tribe or state, or even humanity. Constituted by the body and blood of Christ we participate in God’s Kingdom so that the world may know that we, the church of Jesus Christ, are the end of sacrifice. If Christians leave the Eucharistic table ready to kill one another, we not only eat and drink judgment on ourselves, but we rob the world of the witness necessary for the world to know there is an alternative to the sacrifices of war’.

Stanley Hauerwas on patriotism, pacifism and just warriors

On 2 March 2003, David Rutledge conducted the following interview with Stanley Hauerwas on ABC’s Encounter program:

On 2 March 2003, David Rutledge conducted the following interview with Stanley Hauerwas on ABC’s Encounter program:

David Rutledge: One of the most prominent Christian pacifist voices in the US at the moment is Stanley Hauerwas, from Duke University in North Carolina. His prominence – or notoriety, perhaps – was established by Time magazine in its “America’s Best” issue of 2001, which proclaimed Stanley Hauerwas as “America’s Best Theologian” and ran a profile on him, entitled Christian Contrarian. In that article, he called on Christians not to be defined by their political community, and he condemned “any and all forms of patriotism, nationalism and state worship”. Well that issue of Time magazine hit the newsstands on September 10th, just 24 hours before the terrorist attacks that dramatically altered the American psyche – and that suddenly put Stanley Hauerwas out on the radical fringe of American public life. I asked Stanley Hauerwas if there was anything in that article that he would have changed, had he known that history was about to take the turn that it did.

Stanley Hauerwas: No, not a thing. I suppose that the claim that radical pacifism and Christian non-violence means that you’re critical of all forms of patriotism – I don’t know that I’m critical of “all forms of patriotism”, because I don’t know what “all forms of patriotism” would look like. I’m certainly critical of the kind of patriotism that we find in America. That is the worst kind possible, because it’s not just a loyalty to the particularities of history and geography, but because of America’s basis within the fundamental norms of the Enlightenment – freedom, equality, abstractions like that – then that means American patriotism cannot help but be a form of imperialism. And that’s always the way it has been. And I think it’s one of the most dangerous forms – indeed it’s virulent on the world stage.

Americans can’t understand – I mean, we just – Americans assume that if you just had enough education and enough money, you would want to be just like us – because we’re what free people look like. And therefore American patriotism, I think, is one of the worst forms that could possibly be present in the world.

I think that in America now, we’re really being ruled by the Right. And I think that they have a view of the world that is just not going to be open to any evidence. And so they’re determined to do this. I really believe that this war was on the drawing tables of many of the people that came into the Bush administration. And I think that September 11th was their licence to do it. September 11th determinatively changed American politics, there is absolutely no question about that. The mid-term elections that we just had, in which the Republicans gained seats both in the Senate and the Congress, is really – I mean, that has never happened in America. That’s new. And I think it has everything to do with Americans’ desire for security. September 11th brought the world home to America – and they don’t like it, they just don’t like it. And they’re willing to go with anyone that’s going to promise safety. And that’s what Bush is offering them.

But I really believe, since I’m a Christian, that you always live in a world at risk. Indeed, what Christianity is about, is always learning how to die early for the right reasons. And Americans just – that’s a thought that is unthinkable right now. I think the American response to September 11th is exactly the other side of the Americans’ unbelievable support for crisis care medicine. They think that if we just get good enough at curing cancer, or good enough at doing something about people suffering heart attacks, or good enough with genetics today, then they’re going to get out of this life alive. It’s just not going to happen.

David Rutledge: Can we go back to just war for a minute? You made an interesting comment, that the just war tradition raises the right kinds of questions; but then the just war tradition is seemingly being invoked at the moment as a justification for war. The assumption seems to be that we can and do wage war, so how can we do it and still remain faithful to our Christian ideals. Now as a pacifist, do you think that that is legitimate? How do you evaluate the just war tradition?

Stanley Hauerwas: I’m certainly willing always to join serious just war thinkers in trying to think through what the implications of being a just warrior should be. But if you take the war on Iraq: why is America able to even imagine going to war in Iraq? It’s because we can. We’ve got all this unbelievable military power, so we can envision it, because we have the capacity for it. Now, the question is: did you get the capacity to wage that kind of war on just war considerations? Is the United States’ foreign policy a just war foreign policy? Is the United States’ military preparedness based on just war considerations? No way! They’re based on presuppositions, that you’d better have as much military might as you can, in a world of anarchy, because the one with the most weapons at the end, wins.

Now, if just war people were more serious about raising questions about the implications of what just war would commit them to – for example, the war on terrorism could not possibly be a just war. I don’t even think it’s a war, I mean that’s a metaphorical use of the word “war” that comes from Americans’ views of – you know, the “war on drugs”, the “war on crime” – I mean, it’s just crap. Because what they need to think about is: just war is always about a political end, that you need to declare, so your enemy will know how they can resign and surrender. And so if you’re about annihilating your enemy, as we were in World War II – that is, we fought it for unconditional surrender – you can’t fight a just war for unconditional surrender, because you’re not trying to destroy your enemy, you’re only trying to stop your enemy from doing the wrong that you declared the war for. I mean, there can’t be a just war against terrorism, because you don’t even know who the enemy is, and you get to keep changing it, and the presumption that a just war should be in response to aggression: well, in what way is Iraq really threatening America? That hasn’t been shown at all. What Iraq threatens is American imperial hegemony in the world. How is that a criterion for just war?

So I regard most of the people that are trying to give an account of why it is that the war against Iraq could meet just war criteria, as just an ideological cover for American realism. And notice: no one’s talking about the war on terrorism that much in America right now, because we lost it. Or at least, we haven’t won it. So instead, everyone’s talking about the war against Iraq, and so you’ve made the shift from the war on terrorism to the war against Iraq, which you’re going to win, and so Bush is not being held accountable for the mistaken strategy of ever declaring war against terrorism.

David Rutledge: Theologian and pacifist Stanley Hauerwas, talking earlier this year on the eve of the American attack on Iraq.

Stanley Hauerwas: What I find absolutely crucial is reflecting on Christ’s death and resurrection. What that means is that God would rather die, God would rather have God’s own Son die, than to redeem the world through violence. And that central story is what Christians are about.

Stanley Hauerwas: What I find absolutely crucial is reflecting on Christ’s death and resurrection. What that means is that God would rather die, God would rather have God’s own Son die, than to redeem the world through violence. And that central story is what Christians are about.

I go to an Episcopal church, and after we finish the Mass, one of the prayers that I find a deep comfort is – I just have the Book of Common Prayer here – Eternal God, heavenly Father, you have graciously accepted us as living members of your Son, our saviour Jesus Christ. You have fed us with spiritual food, in the sacrament of His body and blood. Send us now into the world in peace, and grant us strength and courage to love and serve you, with gladness and singleness of heart, through Christ our Lord. Amen. Now, how could someone that prays that prayer every week at the Eucharistic sacrifice – and remember, the Eucharistic sacrifice is where we become part of Christ’s sacrifice for the world, so the world will know it’s got an alternative to violence – how can anyone that prays that prayer, week after week, run for the Presidency of the United States? It beats the hell out of me.

You know, I’m not trying to call Christians out of being politically involved; I just want them to be there as Christians. And instead, what they get is they think they have a personal relationship with Jesus, which makes it OK for them to do anything that they damn well please, in the name of what’s important for national defence. Well, Jesus is a political saviour, and that prayer is a political prayer. And that’s the kind of seizing of the imagination I’m trying to help Christians regain in America. Because in America, Christians just cannot distinguish themselves – what it means to be Christian, they assume it goes hand in hand with what it means to be an American. And that’s just a deep mistake. But how to help Christians recover that difference is very difficult indeed.

David Rutledge: How much help are you getting in that from the American Christian leadership?

Stanley Hauerwas: Well, for example: the Methodist bishops have given a kind of statement against going to war pre-emptively. And you know, they want you to work through the UN, and that kind of thing. They don’t just come out and say “you do it, George, and your soul is going to Hell. Or your soul is already in Hell”. Which I wish they would do. But George Bush, on the whole, is just ignoring any of that kind of statement, because he knows it doesn’t represent the American Methodists. Most American Methodists assume “well, something needs to be done”, and they therefore wouldn’t follow the lead of their bishops.

There’s been quite a number of statements by most of the mainstream religious bodies – you know, saying “go through the UN” and that kind of thing, but it’s had no effect. Because I think that Bush is right: most of the laity doesn’t know how to think about war at all. And the reason most Christian laity don’t know how to think about war at all, is because our religious leadership has never helped educate the American people. As a pacifist, when I go and lecture to churches about the ethics of war, and try to introduce them to just war considerations – because I think that just war is certainly a very serious alternative that people, if they do it seriously, it raises the right kinds of questions that ought to be raised – I usually get a hand stuck up, and someone says “no one’s every told me that Christians have a problem with war”. Isn’t that remarkable? I say “I know you’ve been betrayed. Fire your bishops”. The teaching office of the church has just been absent, over the years, about these kinds of matters.

David Rutledge: There was commentator in the journal First Things, who said that when Christian go off to fight a just war, they’re following Christ, but at a distance. And I wonder if, in your pacifism, you’re talking about something much more immediate, you’re talking about pacifism as the road to Calvary, if it has to be that way, as following Christ in such a way as to be led unresisting to a horrible death, if that’s what your Christianity calls you to do? Is that the kind of end that you have in mind?

Stanley Hauerwas: It certainly could be. I mean, what is the deep problem? The deep problem of Christian non-violence is: you must be willing to watch innocent people suffer for your convictions. Of course, that’s true. In the hard cases, it means it’s not just your death, it’s watching other people die, whom you might have been able to defend. Now of course, you want to try to do everything you can that would prevent that alternative. But you may have to envision that.

But look: the just warriors are in exactly the same position. Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on just war grounds, were murder. There’s no other description for that. Just warriors need to argue that it would have been better for more people to die on the beaches of Japan, both Americans and Japanese, than to commit one murder. That’s what the position should be committed to holding. So of course, any account of serious attempt to morally control war, would mean that if you’re a just warrior, you’re going to have to watch the innocent suffer for your convictions – just like the pacifist does. But on the whole, most people who argue on just war grounds don’t want to acknowledge that. But they should.

David Rutledge: Do you think that one of the key problems for a message like yours, in America or in the world right now, is that when you talk about watching innocent people suffer in the course of a war, the most outstanding recent example of that is the deaths of thousands of Americans at the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon. And the most difficult thing in the world at the moment is for Americans to say “well, in the name of justice, we can’t allow those deaths to be the pretext for more deaths” – even though that’s right at the heart of Christian teaching?

Stanley Hauerwas: Well, I think that Americans simply cannot contemplate Americans getting to die as victims. And they want to turn their deaths into some good. And when they do that, you exactly betray – at least, as Christians – what we should have learned through the Cross: that the attempt to make life meaningful, even life that has died, through further violence, is absolutely futile. But we seem determined to want to do that, and I think we in the world will pay a great price for that. I mean, the price that Americans are going to have to pay for the kind of arrogance that we are operating out of right now, is going to be terrible indeed. And I think that when America isn’t able to rule the world, that people will exact some very strong judgements against America – and I think we will well deserve it.

Around the traps … [updated]

- Podcasts of William Lane Craig on Searching for the Historical Jesus and of William Lane Craig and Shelly Kagan on Is God Necessary for Morality?.

- Ernst Troeltsch and the resurrection: an Easter sermon by Kim Fabricius.

- A new book on Karl Barth: The Trinity and Creation in Karl Barth by Gordon Watson.

- Andrew Sullivan is Thinking Out Loud.

- David Bentley Hart’s bizarre thoughtlessness regarding pacifism by Brian Hamilton. Dave Belcher also posts on David Bentley Hart.

- The New York Times is running some photographs (by Jehad Nga, who was one of American Photo’s Emerging Artists in 2007) and audio of US troops leaving Iraq.

- Protect peaceful Moldovan protesters from police ill-treatment.

- Justine Toh on Clint Eastwood and the ethics of violence.

- And in case you missed it: David’s Ten Theses on Prayer and Ben’s stellar reflection on Led Zeppelin IV.

Pacifism and War: Some Resources [Updated]

I’m trying to put together a list of responsible books/essays that explore theologically questions of Christian pacifism and Christian attitudes to war, and would be keen to hear of such that others have found helpful (and, if possible, why). Here’s what I’ve come up with so far:

I’m trying to put together a list of responsible books/essays that explore theologically questions of Christian pacifism and Christian attitudes to war, and would be keen to hear of such that others have found helpful (and, if possible, why). Here’s what I’ve come up with so far:

Wilma A. Bailey, “You shall not kill” or “You shall not murder”?: The Assault on a Biblical Text (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2005).

Roland H. Bainton, Christian Attitudes Towards War and Peace: A Historical Survey and Critical Re-evaluation (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1960).

Oliver R. Barclay, ed., Pacifism and War (When Christians Disagree) (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1984).

Clive Barrett, ed., Peace Together: A Vision of Christian Pacifism (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 1987).

Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Man of Vision, Man of Courage (New York: Harper & Row, 1970).

Robert W. Brimlow, What About Hitler?: Wrestling with Jesus’s Call to Nonviolence in an Evil World (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2006).

Martin Ceadel, Pacifism in Britain, 1914-45: Defining of a Faith (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1980).

*David L. Clough and Brian Stiltner, Faith and Force: A Christian Debate About War (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2007).

Robert G. Clouse, ed., War: Four Christian Views (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1981).

James Denney, War and the Fear of God (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1916).

Kim Fabricius, Ten Propositions on Peace and War (with a postscript)

Kim Fabricius, Ten Stations on My Way to Christian Pacifism

Gabriella Fiori, Simone Weil: An Intellectual Biography (trans. J.R. Berrigan; Athens/London: University of Georgia Press, 1989).

Peter T. Forsyth, The Christian Ethic of War (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1916).

Peter T. Forsyth, The Justification of God: Lectures for War-Time on a Christian Theodicy (London: Independent Press, 1957).

*Stanley Hauerwas, Against the Nations: War and Survival in a Liberal Society (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1992).

Stanley Hauerwas, Dispatches from the Front: Theological Engagements with the Secular (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994).

Stanley Hauerwas, September 11: A Pacifist Response. From remarks given at the University of Virginia, October 1, 2001.

Stanley Hauerwas, ‘No, This War Would Not Be Moral’, in Time (3 March, 2003).

Stanley Hauerwas and Paul Griffiths, ‘War, Peace & Jean Bethke Elshtain’, in First Things (October, 2003).

Stanley Hauerwas, Performing the Faith: Bonhoeffer and the Practice of Nonviolence (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2004).

Stanley Hauerwas and Jean Vanier, Living Gently in a Violent World: The Prophetic Witness of Weakness (Downers Grove: IVP, 2008).

Eberhard Jüngel, Christ, Justice and Peace: Toward a Theology of the State in Dialogue with the Barmen Declaration (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1992).

Geoffrey A. Studdert Kennedy, Rough Rhymes of a Padre (Toronto: Hodder & Stoughton, 1918).

Geoffrey A. Studdert Kennedy, After War, Is Faith Possible?: The Life and Message of Geoffrey “Woodbine Willie” Studdert Kennedy (ed. Kerry Walters; Eugene: Cascade, 2008). [Reviewed here]

Jean Lasserre, War and the Gospel (London: James Clarke, 1962).

Philip Matthews and David Neville, ‘C.S. Lewis and Christian Pacifism’ in Faith and Freedom: Christian Ethics in a Pluralist Culture (Hindmarsh: ATF Press, 2004), 205-16.

Paul O’Donnell and Stanley Hauerwas, A Pacifist’s Look at Memorial Day: Duke University Divinity professor Stanley Hauerwas on nonviolence, Iraq and killing Hitler.

Oliver O’Donovan, In Pursuit of a Christian View of War (Bramcotte Notts: Grove Books, 1977).

*Oliver O’Donovan, The Just War Revisited (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

George Orwell, ‘Pacifism and the War’, Partisan Review August-September (1942).

Paul Ramsey, War and the Christian Conscience (Durham: Duke University Press, 1968).

Paul Ramsey, The Just War: Force and Political Responsibility (Lanham/Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002).

Alan Ruston, ‘Protestant Nonconformist Attitudes towards the First World War’, in Protestant Nonconformity in the Twentieth Century (ed. Alan P. F. Sell and Anthony R. Cross; Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2003), 240-263. [The book is reviewed here]

*W. J. Sheils, ed., The Church and War: Papers read at the Twenty-first Summer Meeting and the Twenty-second Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1983).

Ronald J. Sider, Christ and Violence (Kitchener: Herald Press, 1979).

*Glen H. Stassen, ed., Just Peacemaking: The New Paradigm for the Ethics of Peace and War (Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 2008).

John Stott, ed., The Year 2000AD (London: Marshalls, 1983), 27-71.

John Stott, Issues Facing Christians Today: New Perspectives on Social and Moral Dilemmas (London: William Collins Sons & Co., 1990), 82-112.

Helmut Thielicke, Theological Ethics Volume 2: Politics (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979).

Miroslav Volf, ‘Christianity and Violence’ (A paper presented at the Boardman Lectureship in Christian Ethics, Boardman Lecture XXXVIII, University of Pennsylvania, 1 March, 2002).

Alan Wilkinson, Dissent or Conform? War, Peace and the English Churches, 1900-1945 (London: SCM Press, 1986).

*John Howard Yoder, The Original Revolution: Essays on Christian Pacifism (Scottdale/Kitchener: Herald Press, 1971).

John Howard Yoder, When War is Unjust: Being Honest in Just-War Thinking (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984).

John Howard Yoder et al., What Would You Do?: A Serious Answer to a Standard Question (Scottsdale/Kitchener: Herald Press, 1983).

John Howard Yoder, Christian Attitudes to War, Peace, and Revolution (ed. Theodore J. Koontz and Andy Alexis-Baker; Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2009).

Supplementary Readings

Terry Eagleton, ‘Isaiah Berlin and Richard Hoggart’ in Figures of Dissent: Critical Essays on Fish, Spivak, Žižek and Others (London/New York: Verso, 2003), 104-8.

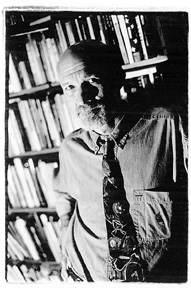

Robert Jenson: Burns Lecture 2 – The Tanakh as Christian Scripture

© 2009. Photo taken by John Roxborogh, when Robert Jenson visited the Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership in Dunedin. Used with permission.

The Burns Lectures are definitely warming up. In this lecture Robert Jenson dealt with the Tanakh, or Old Testament (as is his preferred terminology with appropriate qualification: ‘old’ equals ‘prior’ rather than ‘antiquated’) as Christian scripture. He began by clarifying the appropriate questions – the status of the OT as Christian scripture was never questioned and for Jenson this can’t be the Church’s question since it is both absolutely prior (presumably in the sense that it constitutes the world in which the Christian faith is born) and necessary for the Church’s self-understanding. Jenson says that the really interesting question for the first Christians was a kind of obverse to that which questions the status of Israel’s scriptures, namely whether Israel’s scriptures could accept the proclamation of the resurrection. The Church, he insisted, did not accept Israel’s scriptures. Rather, Israel’s scriptures received the Church. Jenson noted that for the century, it was Israel’s scriptures which served the Gospel rather than the obverse. This question is alive even though it cannot be clearly asked since God has already answered it in raising Jesus.

Jenson proceeded to highlight how this question is constantly in the background of NT writing and how the NT demonstrates in the way it tells its story a ‘narrative harmony’ with Israel’s scriptures – relationship between passion narrative and Isaiah 53 being a case in point. The OT prophets were the one’s who provided the answer to ‘why’ did Jesus needed to die. Jenson argued that we cannot ask why the OT Scripture after Christ. Rather, we can only ask how scripture is the way for the Christian community. He also observed that the Church reads the OT as narrative because her gospel is itself a narrative, and because her gospel recognizes itself as the climax of the story told in the OT. Jenson cautioned about ‘unguarded talk of the unique fullness of God’s revelation in Christ’ [is that the mythological Christomonism?]. Such talk requires, says Jenson, the important qualification that the God present to the OT sages is the same Word, Jesus Christ. Jesus taught the scriptures with ‘authority’ says Jenson, ‘that is, as if he were the author … because, in a sense, he is’. Jenson continued this line with comments like ‘Christ prayed the psalms as the leader of Israel’s worship gathered as the body of Christ’. When ancient Israel gathered in the temple with their hymns and lamentations they were gathered as ‘the body of Christ’. At this point he introduced some of the difficult issues that were to arise later in his lecture also. In response to those who wonder whether Christians can pray the Psalms that call for the destruction of their enemies and the bashing of babies against rocks, he suggested, with some rhetorical flourish, that they could pray them at the foot of the cross against the devil and his angels. [We shall return to this claim]

The key question which the latter part of Jenson’s lecture focuses on is not whether the OT is Christian scripture but precisely how it so functions. Jenson’s answer is that it functions as ‘narrative of God’s history with his people’, including the Church. This arises because the Church’s gospel is narrative and it identifies itself as the climax of the narrative of Israel’s history. Why this should be so stems from the character of the ‘regula fidei’ as a ‘plotted sequence of God’s acts’ (economy) on the one hand and the nature of the book the Church wrote as a second testament. He interestingly contrasts the two movements to emerge from old Israel with the destruction of the temple – rabbinic Judaism ended up using the Tanakh differently from the Church because their second testament (Mishnah) had a legal character which meant that they read their Torah with law as a guiding concept. On the other hand the Church with its narrative gospel ended up contextualising law within the narrative of God with his people. This also had a lot to do with Paul’s very complex problematisation of the law.

The ‘how’ question in relation to the role of the OT was forged in contrast to various challenges to the initial role of the OT – Gnosticism, Marcionism, and Platonism. Although there was a certain ‘Church History 101’ feel to the lecture here, Jenson’s characterization of the movements and issues was always interesting. In response to all these developments, but particularly to that ‘monomaniacal Paulinist’ Marcion, Jenson says that Christians have no way of avoiding the fact that the God of Israel is a ‘man of war’ who goes into battle, sometimes for, sometimes against, his people, but a God who takes sides in history. This, says Jenson, is the only alternative to a god who abandons history. God is either involved in fallen history as the God of Israel is, or God is not. If God is to engage a violent history God cannot do so without being a ‘God of war’, that is, without getting God’s hands dirty. And it seems, for Jenson, to be involved is to be implicated as an agent of violence. Like Hans Boersma has also recently argued, Jenson seems to hold that God uses violence as a means justified by God’s ends – that God participates in the world’s violence but he does so by entering into that violence and dying in it, through which violence is undone.

When questioned as to whether there was a third alternative, namely to suffer violence as the crucified one, Jenson responded effectively that in relation to this issue it was not really a third alternative since the crucifixion was an event in which God was both the crucifier and the crucified – and therefore, presumably, not non-violent. He also presumed that the question was motivated by the issue of theodicy.

Three critical questions arise at this point:

- The first picks up on the difference the revelation of God in Christ makes. Why did Jenson limit the praying of that psalm to prayers against “the devil and his angels”? If he is to be consistently true to the ‘man of war’ motif, why do not Christians pray against their human enemies and their enemy’s babies? And if they do so, how is this consistent with love for one’s enemies?

- Is it necessary that if the Father sent the Son to the cross and the Son went to the cross in obedience to the Father that the God of Israel must be seen as both the crucified and the crucifier? Surely the willingness to be crucified and the willingness to let the Son be crucified (not my will but yours) do not entail the agency of crucifixion. Surely the fact that this evil event is ultimately good (Friday) lies in the good consequent upon it (for the joy that was set before him). There is no paradoxical necessity to make God (in whom there is no darkness) the agent of death. Surely the triune God is here its defeater.

- Finally, does the fact that the Old Testament is the Church’s scripture rule out the possibility that it, like the New Testament, is a ‘text in travail’ bearing witness to Israel education by God. Is it not possible to discern in the light of the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ a journey within Israel to unlearn pagan violence – we think here of a trajectory which includes the Cain/Abel story, the Akideh, the repentance of God post flood, the Joseph story, story of Job, the servant songs and so much more. So rather than accepting a strand which is taken for granted in the scriptures – God as man of war – why not discern how that strand is being deconstructed in the course of Israel’s journey with God? If such a reading is persuasive then the motivation to question the ‘man of war’ motif need not be motivated by theodicy, or not in any simplistic way.

Past Lectures:

1. Creed, Scripture, and Their Modern Alienation

Following Lectures:

3. The New Testament and the Regula Fidei

5. The Creed as Critical Theory of Scripture

6. Genesis 1:1 and Luke 1:26-38

Notes by Bruce Hamill and Jason Goroncy

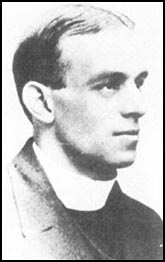

‘After War, Is Faith Possible?’: A Commendation

Geoffrey A. Studdert Kennedy, After War, Is Faith Possible?: The Life and Message of Geoffrey “Woodbine Willie” Studdert Kennedy (ed. Kerry Walters; Eugene: Cascade, 2008). xii + 225 pages. ISBN: 978-1-55635-379-6. Review copy courtesy of Wipf and Stock.

Geoffrey A. Studdert Kennedy, After War, Is Faith Possible?: The Life and Message of Geoffrey “Woodbine Willie” Studdert Kennedy (ed. Kerry Walters; Eugene: Cascade, 2008). xii + 225 pages. ISBN: 978-1-55635-379-6. Review copy courtesy of Wipf and Stock.

One the real delights of my research into the thought of PT Forsyth has been revisiting, and in some cases discovering for the first time, others who were writing around the same time, and often of the same events. To re-read James Denney, or James Baldwin Brown, or FD Maurice, is one of the best ways one could spend a month … or two. Another giant personality to add to that list would have to be Geoffrey A. Studdert Kennedy, better known as ‘Woodbine Willie’. (I posted on ) My copies of Studdert Kennedy’s work, which are all over 90 years old, form a truly valuable part of my library and one to which I return not infrequently. Collected Poetry (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1927), The Hardest Part (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1918), I Believe: Sermons on the Apostles Creed (New York: George H. Doran, 1921), Rough Rhymes of a Padre (Toronto: Hodder & Stoughton, 1918) and The Wicket Gate, or Plain Bread (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923) all constitute exceptional reading.

And so I was absolutely delighted to discover that Wipf & Stock decided to republish some Woodbine Willie excerpts, all well chosen and just enough to plant an appetite in those who will no doubt want to hear more from ‘the bloody parson!’ (p. 12). The collection was edited by Kerry Walters, who also contributed a very fine introduction on Studdert Kennedy’s life and message, and a helpful bibliography of the primary and secondary literature.

This WWI padre was, of course, one of the best-known and most-loved Christian pacifists of the early twentieth century. Unlike those theological yuppies who defend pacifism on purely ideological grounds and over a café latte in Lygon Street – informed by the Gospel or otherwise – Woodbine Willie’s commitment to pacifism was birthed in the trenches alongside frightened men and their dead mates. In all that he wrote, a number of questions incessantly occupied his thought: ‘Given the insanity and brutality of war (‘the universal disaster’; p. 14), what must the God who allows it be like? (p. 13); How is evil to be gotten rid of? (p. 3); What sort of universe ought an honest person believe in? (p. 15). His answer to these questions eventually led to the conviction that God is not sadistic, or indifferent to the world’s evil. Neither is God ‘Almighty’ enough to prevent such evils: ‘I see no evidence anywhere in nature of the Almighty Potentate Who guides and governs all things with His rod, and knows no failure and thwarting of His Will’ (p. 81). What God does do, Woodbine Willie insists (in Moltmannesque manner), is to suffer with and alongside humanity. This is love’s character – not raw despotic power but entering into the sorrows of the beloved. War then, which is evil in its most acute form, is ‘the test case for determining if Christianity can cope with evil’ (p. 21).

Against those who would ‘blather’ about the ‘glory of war’, or who would hold out hope for war being a converting ordinance, Woodbine Willie says that ‘war is pure undiluted, filthy sin. I don’t believe that it has ever redeemed a single soul – or ever will’ (p. 62):

War is only glorious when you buy it in the Daily Mail and enjoy it at the breakfast table. It goes splendidly with bacon and eggs. Real war is the final limit of damnable brutality, and that all there is in it. It’s about the silliest, filthiest, most inhumanly fatuous thing that ever happened. It makes the whole universe seem like a mad muddle. One feels that all talk of order and meaning in life is insane sentimentality. (p. 41)

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy speaking at Tredegar during an Industrial Christian Fellowship Crusade in 1928.

There are no words foul and filthy enough to describe war. Yet I would remind you that this indescribably filthy thing is the commonest thing in History, and that if we believe in a God of Love at all we must believe in the face of war and all it means. The supreme strength of the Christian faith is that it faces the foulest and filthiest of life’s facts in the crude brutality of the Cross, and through them sees the Glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ. (p. 49)

Waste of Muscle, waste of Brain,

Waste of Patience, waste of Pain,

Waste of Manhood, waste of Health,

Waste of Beauty, waste of Wealth,

Waste of Blood, and waste of Tears,

Waste of Youth’s most precious years,

Waste of ways the Saints have trod,

Waste of Glory, waste of God –

War! (p. 50)

I cannot say that war, disease, pestilence, famine, and all the other characteristics of the process are good. If this word “Almighty” means that the Father could have made this world, and obtained the results He desires, in a thousand other ways, but that He deliberately chose this, that makes my gorge rise. Why in thunder choose this one? It is disreputable if He could have done it otherwise, without this cruelty and wrong. It is not commonly respectable. He must be an evil-minded blackguard, with a nasty disposition like a boy that likes pulling the wings off flies. I cannot get up any reverence for such a being. Why, bless my life, He tortures children, voluntarily tortures them to death, and has done so for thousands of years. I can’t stand that at all – it’s dirty; and when I am told that I must believe it, and that every detail of the process was planned out precisely as He wished, I begin to turn sick. Snakes, sharks, and blood-sucking vermin – what sort of a God is this? He chose this way because He gloried in it! That beats the band. It turns me clean up against the process. I cannot see its beauty for its brutality. I cannot hear the lark sing for the squealing of a rabbit tortured by a stoat, I cannot see the flowers for the face of a consumptive child with rotten teeth, the song of the saints is drowned by the groans of murdered men. (p. 75)

A soldier in time of war is not a person but a puppet, who moves when you pull strings. (p. 78)

… our armaments are symbols, not of our power, but of our weakness … Our military power is an exact index of our spiritual and moral impotence. (p. 79)

Life is one, from the single cell to the Savior in the flesh. I cannot separate swine from Shakespeare or Jellyfish from Jesus of Nazareth; they all are products of the process. So behind the process there must be a Spirit which is like the Spirit of man. (p. 81)

I am not a pacifist (I’ve been too persuaded by Forsyth and Jüngel here), but reading Woodbine Willie continuously challenges me to ask myself whether I should be, whether our Lord’s command to ‘Love your enemies’ (Matt 5:44) really does, in Barth’s words, abolish ‘the whole exercise of force’. Either way, Barth is most certainly correct when he challenges: ‘In conformity with the New Testament, one can be pacifist not in principle but only in practice (praktisch Pazifist). But let everyone consider very carefully whether, being called to discipleship, it is possible to avoid – or permissible to neglect – becoming a practical pacifist!’ (Church Dogmatics IV/2, 549-50).

I am not a pacifist (I’ve been too persuaded by Forsyth and Jüngel here), but reading Woodbine Willie continuously challenges me to ask myself whether I should be, whether our Lord’s command to ‘Love your enemies’ (Matt 5:44) really does, in Barth’s words, abolish ‘the whole exercise of force’. Either way, Barth is most certainly correct when he challenges: ‘In conformity with the New Testament, one can be pacifist not in principle but only in practice (praktisch Pazifist). But let everyone consider very carefully whether, being called to discipleship, it is possible to avoid – or permissible to neglect – becoming a practical pacifist!’ (Church Dogmatics IV/2, 549-50).

Faith does not mean that we cease from asking questions; it means that we ask and keep on asking until the answer comes; that we seek and keep on seeking until the truth is found; that we knock and keep on knocking until the door is opened and we enter into the palace of God’s truth. (p. 63)

Woodbine Willie dares us to keep on prayerfully asking the questions …

If the Church is to be a Church indeed, and not a mere farce – and a peculiarly pernicious farce, a game of sentimental make-believe – she must be filled to overflowing with the fire of the ancient prophets for social righteousness, with the wrath and love of the Christ. (p. 196)

The Church is not, and never can be, an end in itself; it is a means to an end; a means to the salvation of the world and the building of the Kingdom of God. It is not the Ark of Salvation for themselves, it is the Agent of Salvation for mankind. It is not a refuge of peace, but an army preparing for war. They seek in it, not security, but sacrifice. This is the infallible mark of the Church, the hallmark of the Cross. And if the sin of our modern slums, and the degradation that they cause; if the sin of our over-crowded, rotten houses, and the ugliness and vice they bring; if the sin of unemployment, with the damnation of body and soul that it means to men and women, boys and girls; if the sin of the heartless, thoughtless luxury at one end, standing out against the squalid and degrading poverty at the other; if the sin of commercial trickery and dishonesty, and wholesale defrauding of the poor; if the sin of prostitution, and the murder of women and children by venereal disease; if the sin of war, the very sin of sins, which is but the bursting into a festering sore of all the filth that the others have bred in years of miscalled peace; if all that is not laid upon the Church as a burden, and Christ’s members do not feel it as their own, then the Church is not a Church at all; and no amount of organization, propaganda, and evangelization can make it live. It has missed its vocation. (p. 167)

John Pilger on ‘The politics of bollocks’

While much of the world has been observing the post-election balloons starting to deflate, the last streamers being swept up, and the last drop of bubbly being sculled (though some of us have now refilled our flutes after recent news), John Pilger‘s gutsy pen has been resisting all efforts to shut up and be grateful that at least President Bush is gone. It’s time, he says, for Obama-lovers to grow up. He is, of course, right. Here’s Pilger piece published in yesterday’s New Statesman:

While much of the world has been observing the post-election balloons starting to deflate, the last streamers being swept up, and the last drop of bubbly being sculled (though some of us have now refilled our flutes after recent news), John Pilger‘s gutsy pen has been resisting all efforts to shut up and be grateful that at least President Bush is gone. It’s time, he says, for Obama-lovers to grow up. He is, of course, right. Here’s Pilger piece published in yesterday’s New Statesman:

‘Growing up in an Antipodean society proud of its rich variety of expletives, I never heard the word bollocks. It was only on arrival in England that I understood its magisterial power. All classes used it. Judges grunted it; an editor of the Daily Mirror used it as noun, adjective and verb. Certainly, the resonance of a double vowel saw off its closest American contender. It had authority.

A high official with the Gilbertian title of Lord West of Spithead used it to great effect on 27 January. The former admiral, who is a security adviser to Gordon Brown, was referring to Tony Blair’s assertion that invading countries and killing innocent people did not increase the threat of terrorism at home.

“That was clearly bollocks,” said his lordship, who warned of a perceived “linkage between the US, Israel and the UK” in the horrors inflicted on Gaza and the effect on the recruitment of terrorists in Britain. In other words, he was stating the obvious: that state terrorism begets individual or group terrorism at source. Just as Blair was the prime mover of the London bombings of 7 July 2005, so Brown, having pursued the same cynical crusades in Muslim countries and having armed and disported himself before the criminal regime in Tel Aviv, will share responsibility for related atrocities at home.

There is a lot of bollocks about at the moment.

The BBC’s explanation for banning an appeal on behalf of the stricken people of Gaza is a vivid example. Mark Thompson, the BBC’s director general, cited the corporation’s legal requirement to be “impartial . . . because Gaza remains a major ongoing news story in which humanitarian issues . . . are both at the heart of the story and contentious”.

In a letter to Thompson, David Bracewell, a licence-fee payer, illuminated the deceit behind this. He pointed to previous BBC appeals for the Disasters Emergency Committee that were not only made in the midst of “an ongoing news story” in which humanitarian issues were “contentious”, but also demonstrated how the corporation took sides.

In 1999, at the height of the illegal Nato bombing of Serbia and Kosovo, the TV presenter Jill Dando made an appeal on behalf of Kosovar refugees. The BBC web page for that appeal was linked to numerous articles meant to stress the gravity of the humanitarian issue. These included quotations from Blair himself, such as: “This will be a daily pounding until he [Slobodan Milosevic] comes into line with the terms that Nato has laid down.” There was no significant balance of view from the Yugoslav side, and not a single mention that the flight of Kosovar refugees began only after Nato had started bombing.

Similarly, in an appeal for victims of the civil war in the Congo, the BBC favoured the regime led by Joseph Kabila by not referring to Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and other reports accusing his forces of atrocities. In contrast, the rebel leader Laurent Nkunda was “accused of committing atrocities” and ordained the bad guy by the BBC. Kabila, who represented western interests, was clearly the good guy – just like Nato in the Balkans and Israel in the Middle East.

While Mark Thompson and his satraps richly deserve the Lord West of Spithead Bollocks Blue Ribbon, that honour goes to the cheer squad of President Barack Obama, whose cult-like obeisance goes on and on.

On 23 January, the Guardian‘s front page declared, “Obama shuts network of CIA ‘ghost prisons'”. The “wholesale deconstruction [sic] of George Bush’s war on terror”, said the report, had been ordered by the new president, who would be “shutting down the CIA’s secret prison network, banning torture and rendition . . .”

The bollocks quotient on this was so high that it read like the press release it was, citing “officials briefing reporters at the White House yesterday”. Obama’s orders, according to a group of 16 retired generals and admirals who attended a presidential signing ceremony, “would restore America’s moral standing in the world”. What moral standing? It never ceases to astonish that experienced reporters can transmit PR stunts like this, bearing in mind the moving belt of lies from the same source under only nominally different management.

Far from “deconstructing the war on terror”, Obama is clearly pursuing it with the same vigour, ideological backing and deception as the previous administration. George W Bush’s first war, in Afghanistan, and last war, in Pakistan, are now Obama’s wars – with thousands more US troops to be deployed, more bombing and more slaughter of civilians. Last month, on the day he described Afghanistan and Pakistan as “the central front in our enduring struggle against terrorism and extremism”, 22 Afghan civilians died beneath Obama’s bombs in a hamlet populated mainly by shepherds and which, by all accounts, had not laid eyes on the Taliban. Women and children were among the dead, which is normal.

Far from “shutting down the CIA’s secret prison network”, Obama’s executive orders actually give the CIA authority to carry out renditions, abductions and transfers of prisoners in secret without threat of legal obstruction. As theLos Angeles Times disclosed, “current and former US intelligence officials said that the rendition programme might be poised to play an expanded role”. A semantic sleight of hand is that “long-term prisons” are changed to “short-term prisons”; and while Americans are now banned from directly torturing people, foreigners working for the US are not. This means that America’s numerous “covert actions” will operate as they did under previous presidents, with proxy regimes, such as Augusto Pinochet’s in Chile, doing the dirtiest work.

Bush’s open support for torture, and Donald Rumsfeld’s extraordinary personal overseeing of certain torture techniques, upset many in America’s “secret army” of subversive military and intelligence operators because it exposed how the system worked. Obama’s newly confirmed director of national intelligence, Admiral Dennis Blair, has said the Army Field Manual may include new forms of “harsh interrogation” which will be kept secret.

Obama has chosen not to stop any of this. Neither do his ballyhooed executive orders put an end to Bush’s assault on constitutional and international law. He has retained Bush’s “right” to imprison anyone, without trial or charge. No “ghost prisoners” are being released or are due to be tried before a civilian court. His nominee for attorney general, Eric Holder, has endorsed an extension of Bush’s totalitarian USA Patriot Act, which allows federal agents to demand Americans’ library and bookshop records. The man of “change” is changing little. That ought to be front-page news from Washington.

The Lord West of Spithead Bollocks Prize (Runner-Up) is shared. On 28 January, a nationally run Greenpeace advertisement opposing a third runway at Heathrow Airport in London summed up the almost wilful naivety that has obstructed informed analysis of the Obama administration.

“Fortunately,” declared Greenpeace beneath a Godlike picture of Obama, “the White House has a new occupant, and he has asked us all to roll back the spectre of a warming planet.” This was followed by Obama’s rhetorical flourish about “putting off unpleasant decisions”. In fact, the president has made no commitment to curtail America’s infamous responsibility for the causes of global warming. As with George W Bush and most other modern-era presidents, it is oil, not stemming carbon emissions, that informs his administration. His national security adviser, General Jim Jones, a former Nato supreme commander, made his name planning US military control over the exploitation of oil and gas reserves from the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea to the Gulf of Guinea off Africa.

Sharing the Bollocks Runner-Up Prize is the Observer, which on 25 January published a major news report headlined, “How Obama set the tone for a new US revolution”. This was reminiscent of the Observer almost a dozen years ago when liberalism’s other great white hope, Tony Blair, came to power. “Goodbye xenophobia” was the Observer‘s post-election front page in 1997 and “The Foreign Office says ‘Hello World, remember us?'”. The government, said the breathless text, would push for “new worldwide rules on human rights and the environment” and implement “tough new limits” on arms sales. The opposite happened. Last year, Britain was the biggest arms dealer in the world; currently, it is second only to the United States.

In the Blair mould, the Obama White House “sprang into action” with its “radical plans”. The president’s first phone call was to that Palestinian quisling, the unelected and deeply unpopular Mahmoud Abbas. There was a “hot pace” and a “new era”, in which a notorious name from an ancien régime, Richard Holbrooke, was despatched to Pakistan. In 1978, Holbrooke betrayed a promise to normalise relations with the Vietnamese on the eve of a vicious embargo ruined the lives of countless Vietnamese children. Under Obama, the “sense of a new era abroad”, declared the Observer, “was reinforced by the confirmation of Hillary Clinton as secretary of state”. Clinton has threatened to “entirely obliterate Iran” on behalf of Israel.

What the childish fawning over Obama obscures is the dark power assembled under cover of America’s first “post-racial president”. Apart from the US, the world’s most dangerous state is demonstrably Israel, having recently killed and maimed some 4,000 people in Gaza with impunity. On 10 February, a bellicose Israeli electorate is likely to put Binyamin Netanyahu into power. Netanyahu is a fanatic’s fanatic who has made clear his intention of attacking Iran. In the Wall Street Journal of 24 January, he described Iran as the “terrorist mother base” and justified the murder of civilians in Gaza because “Israel cannot accept an Iranian terror base [Gaza] next to its major cities”. On 31 January, unaware he was being filmed, Tel Aviv’s ambassador to Australia described the massacres in Gaza as a “pre-introduction” – a dress rehearsal – for an attack on Iran.

For Netanyahu, the reassuring news is that the new US administration is the most Zionist in living memory, a truth that has struggled to be told from beneath the soggy layers of Obama-love. Not a single member of the president’s team demurred from his support for Israel’s barbaric actions in Gaza. Obama himself likened the safety of his two young daughters with that of Israeli children but made not a single reference to the thousands of Palestinian children killed with American weapons – a violation of both international and US law. He did, however, demand that the people of Gaza be denied “smuggled” small arms with which to defend themselves against the world’s fourth-largest military power. And he paid tribute to the Arab dictatorships, such as Egypt, which are bribed by the US treasury to help the United States and Israel enforce policies described by the UN special rapporteur Richard Falk, a Jew, as “genocidal”.

It is time the Obama lovers grew up. It is time those paid to keep the record straight gave us the opportunity to debate informatively. In the 21st century, people power remains a huge and exciting and largely untapped force for change, but it is nothing without truth. “In the time of universal deceit,” wrote George Orwell, “telling the truth is a revolutionary act.”

Chomsky on ‘”Exterminate all the Brutes”: Gaza 2009’

On Saturday December 27, the latest US-Israeli attack on helpless Palestinians was launched. The attack had been meticulously planned, for over 6 months according to the Israeli press. The planning had two components: military and propaganda. It was based on the lessons of Israel’s 2006 invasion of Lebanon, which was considered to be poorly planned and badly advertised. We may, therefore, be fairly confident that most of what has been done and said was pre-planned and intended.

On Saturday December 27, the latest US-Israeli attack on helpless Palestinians was launched. The attack had been meticulously planned, for over 6 months according to the Israeli press. The planning had two components: military and propaganda. It was based on the lessons of Israel’s 2006 invasion of Lebanon, which was considered to be poorly planned and badly advertised. We may, therefore, be fairly confident that most of what has been done and said was pre-planned and intended.

That surely includes the timing of the assault: shortly before noon, when children were returning from school and crowds were milling in the streets of densely populated Gaza City. It took only a few minutes to kill over 225 people and wound 700, an auspicious opening to the mass slaughter of defenseless civilians trapped in a tiny cage with nowhere to flee.

In his retrospective “Parsing Gains of Gaza War,” New York Times correspondent Ethan Bronner cited this achievement as one of the most significant of the gains. Israel calculated that it would be advantageous to appear to “go crazy,” causing vastly disproportionate terror, a doctrine that traces back to the 1950s. “The Palestinians in Gaza got the message on the first day,” Bronner wrote, “when Israeli warplanes struck numerous targets simultaneously in the middle of a Saturday morning. Some 200 were killed instantly, shocking Hamas and indeed all of Gaza.” The tactic of “going crazy” appears to have been successful, Bronner concluded: there are “limited indications that the people of Gaza felt such pain from this war that they will seek to rein in Hamas,” the elected government. That is another long-standing doctrine of state terror. I don’t, incidentally, recall the Times retrospective “Parsing Gains of Chechnya War,” though the gains were great.

The meticulous planning also presumably included the termination of the assault, carefully timed to be just before the inauguration, so as to minimize the (remote) threat that Obama might have to say some words critical of these vicious US-supported crimes.

Two weeks after the Sabbath opening of the assault, with much of Gaza already pounded to rubble and the death toll approaching 1000, the UN Agency UNRWA, on which most Gazans depend for survival, announced that the Israeli military refused to allow aid shipments to Gaza, saying that the crossings were closed for the Sabbath. To honor the holy day, Palestinians at the edge of survival must be denied food and medicine, while hundreds can be slaughtered by US jet bombers and helicopters.

The rigorous observance of the Sabbath in this dual fashion attracted little if any notice. That makes sense. In the annals of US-Israeli criminality, such cruelty and cynicism scarcely merit more than a footnote. They are too familiar. To cite one relevant parallel, in June 1982 the US-backed Israeli invasion of Lebanon opened with the bombing of the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, later to become famous as the site of terrible massacres supervised by the IDF (Israeli “Defense” Forces). The bombing hit the local hospital – the Gaza hospital – and killed over 200 people, according to the eyewitness account of an American Middle East academic specialist. The massacre was the opening act in an invasion that slaughtered some 15-20,000 people and destroyed much of southern Lebanon and Beirut, proceeding with crucial US military and diplomatic support. That included vetoes of Security Council resolutions seeking to halt the criminal aggression that was undertaken, as scarcely concealed, to defend Israel from the threat of peaceful political settlement, contrary to many convenient fabrications about Israelis suffering under intense rocketing, a fantasy of apologists.

All of this is normal, and quite openly discussed by high Israeli officials. Thirty years ago Chief of Staff Mordechai Gur observed that since 1948, “we have been fighting against a population that lives in villages and cities.” As Israel’s most prominent military analyst, Zeev Schiff, summarized his remarks, “the Israeli Army has always struck civilian populations, purposely and consciously…the Army, he said, has never distinguished civilian [from military] targets…[but] purposely attacked civilian targets.” The reasons were explained by the distinguished statesman Abba Eban: “there was a rational prospect, ultimately fulfilled, that affected populations would exert pressure for the cessation of hostilities.” The effect, as Eban well understood, would be to allow Israel to implement, undisturbed, its programs of illegal expansion and harsh repression. Eban was commenting on a review of Labor government attacks against civilians by Prime Minister Begin, presenting a picture, Eban said, “of an Israel wantonly inflicting every possible measure of death and anguish on civilian populations in a mood reminiscent of regimes which neither Mr.Begin nor I would dare to mention by name.” Eban did not contest the facts that Begin reviewed, but criticized him for stating them publicly. Nor did it concern Eban, or his admirers, that his advocacy of massive state terror is also reminiscent of regimes he would not dare to mention by name.

Eban’s justification for state terror is regarded as persuasive by respected authorities. As the current US-Israel assault raged, Times columnist Thomas Friedman explained that Israel’s tactics both in the current attack and in its invasion of Lebanon in 2006 are based on the sound principle of “trying to `educate’ Hamas, by inflicting a heavy death toll on Hamas militants and heavy pain on the Gaza population.” That makes sense on pragmatic grounds, as it did in Lebanon, where “the only long-term source of deterrence was to exact enough pain on the civilians – the families and employers of the militants – to restrain Hezbollah in the future.” And by similar logic, bin Laden’s effort to “educate” Americans on 9/11 was highly praiseworthy, as were the Nazi attacks on Lidice and Oradour, Putin’s destruction of Grozny, and other notable attempts at “education.”

Israel has taken pains to make clear its dedication to these guiding principles. NYT correspondent Stephen Erlanger reports that Israeli human rights groups are “troubled by Israel’s strikes on buildings they believe should be classified as civilian, like the parliament, police stations and the presidential palace” – and, we may add, villages, homes, densely populated refugee camps, water and sewage systems, hospitals, schools and universities, mosques, UN relief facilities, ambulances, and indeed anything that might relieve the pain of the unworthy victims. A senior Israeli intelligence officer explained that the IDF attacked “both aspects of Hamas – its resistance or military wing and its dawa, or social wing,” the latter a euphemism for the civilian society. “He argued that Hamas was all of a piece,” Erlanger continues, “and in a war, its instruments of political and social control were as legitimate a target as its rocket caches.” Erlanger and his editors add no comment about the open advocacy, and practice, of massive terrorism targeting civilians, though correspondents and columnists signal their tolerance or even explicit advocacy of war crimes, as noted. But keeping to the norm, Erlanger does not fail to stress that Hamas rocketing is “an obvious violation of the principle of discrimination and fits the classic definition of terrorism.”