The demise of the local book shop is more than a mere kink in the history of civilisation as we know it. It is a sign that the end is nigh, that the four horsemen have donned their stirrups, and that the fiancée of God better get her nickers on and her face spruced up quick smart.

The demise of the local book shop is more than a mere kink in the history of civilisation as we know it. It is a sign that the end is nigh, that the four horsemen have donned their stirrups, and that the fiancée of God better get her nickers on and her face spruced up quick smart.

Of course, the sad and dangling sign that reads ‘Closing Down’ also announces an opportunity for the sagacious book buyer to exploit the situation to the absolute hilt, and to put some further pressure on the stumps that hold up that corner of the house where the library is situated.

Such is the situation a mere stones throw away from my study; or at least a stones throw away for someone who possesses omnipotent stone-throwing capabilities. I visited that scene of negation three times last week, and each time feeling somewhat like the grim reaper I have walked out with at least two bags of books – at $2 a book! – evidence, among other things, of one of my many addictions … and of my intelligent tastes.

The first time I stumbled into this sacrament of culture’s demise (as much to get out of the rain as for anything else I’m ashamed to say) I stumbled not to buy, not on this occassion anyway, but simply to smell pages. With the rising waft of wet carpet and the air reeking of the body odour of some forty-something woman who was hogging the self-help section, I was encouraged (is that too weak a word?) to move on to the cookbook section (one of my favourites), and then, just around the corner, as if my nose had discovered the smell of sweet basil for the first time, I was conjoined to the poetry section. ‘Section’ is perhaps too inflated a word to describe what was the smallest collection of poetry books you could imagine in a book shop; there must have been fewer than 30 volumes. But among that lot, two stupefied my cornea – Roy Fuller’s Owls and Artificers: Oxford Lectures on Poetry (not technically a book of poems, but when the pickins is slim and all that) and Collected Poems by a Dunedin-based poet that I had never heard of, a man by the name of John Paisley.

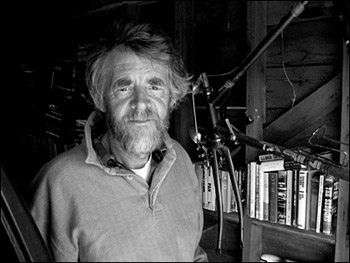

After reading the first few dozen poems by Paisley, I was intrigued and I wanted to know more about their author. To be sure, it’s not that all of his poems are wonderful – they aren’t; but there’s something about Paisley’s spirit that gripped me last week, and since too. I want to know more about this man, and the more I find out, the more fascinated I am, and the more I want to know. Thus far, here’s what I’ve been able to find out about John Paisley: He was born in Wellington in 1938; four years later his family moved to Dunedin. He attended Waitaki Boys’ High School and then the University of Otago, where he completed an MA in English on the poets Charles Brasch and James K. Baxter (to whose memory he penned the poem ‘Community at Jerusalem’). He commenced training as a Presbyterian minister at Knox College (where I work), but had to withdraw due to ill health. His sister, Dawn Ross, in a wee introduction to his Collected Poems, described her brother as ‘an eccentric person’ and as ‘different’. He later travelled to and lived in a variety of places, and held down a number of jobs. He wrote numerous poems and performed at poetry readings. He had one poetry collection (This Night in Winter) published during his lifetime, and two further collections were published following his death (Vigils and Collected Poems).

After reading the first few dozen poems by Paisley, I was intrigued and I wanted to know more about their author. To be sure, it’s not that all of his poems are wonderful – they aren’t; but there’s something about Paisley’s spirit that gripped me last week, and since too. I want to know more about this man, and the more I find out, the more fascinated I am, and the more I want to know. Thus far, here’s what I’ve been able to find out about John Paisley: He was born in Wellington in 1938; four years later his family moved to Dunedin. He attended Waitaki Boys’ High School and then the University of Otago, where he completed an MA in English on the poets Charles Brasch and James K. Baxter (to whose memory he penned the poem ‘Community at Jerusalem’). He commenced training as a Presbyterian minister at Knox College (where I work), but had to withdraw due to ill health. His sister, Dawn Ross, in a wee introduction to his Collected Poems, described her brother as ‘an eccentric person’ and as ‘different’. He later travelled to and lived in a variety of places, and held down a number of jobs. He wrote numerous poems and performed at poetry readings. He had one poetry collection (This Night in Winter) published during his lifetime, and two further collections were published following his death (Vigils and Collected Poems).

In a short essay, ‘Commentary on Religious Poems for Reading’, Paisley describes his own work as a poet thus:

I make no claims to be a religious poet myself. If anything, I am perhaps a poet who writes the occasional religious poem. But while most of the time my attention and my writing is taken up with other and more secular concerns, my religious poetry is important and significant to me and my development, both as a person and as a writer. It is not without significance that when many years ago I lost contact with reality for a few weeks altogether, I attended a party at the house of a friend and for sometime recited a long religious poem (spontaneously composed) to a room full of surprised and eventually indifferent guests. The poem is not among my papers, and I have no memory of having ever written it. But the fact that even in the state of insanity, my preoccupation was a religious one, speaks volumes in itself.

And about poetry itself, he writes:

It is easy for us to forget in the 20th century how closely the poetic spirit and vision is bound up with religion. In our tradition – the Judaic Christian one, there is a long line of poets beginning at Moses and the author of the book of Job, with David, Solomon and Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the other prophets and ending i with Jesus and St. John. The Bible was only the beginning, the list is endless and will only mention one now – St. John of the Cross – the beauty of whose poetry approaches the angelic.

Poetry in general and religious poetry in particular has at its heart the metaphor, which is a figure of speech where one object comes to represent or stand for another, for example, take William Blake (another great religious poet of last century), who said when he looked at the sun, he saw a choir of angels. It also has at its heart the myth which is a story which has a metaphorical meaning. Nowadays, we have so lost contact with the Poetic vision that we find it very difficult to understand the myths of the past and even more difficult to create our own myths in order to interpret our experience of life, and this disability on our part can become dangerous. When our myths become inarticulate, or we try to live without them, they enter into the dark depths of our subconscious and their presence there becomes a constant source of danger, a smouldering furnace springing up from time to time with the destructive force of a supposedly extinct volcano. Only when our imagination has been captured and put to work in a realm in which it has room to breathe and move, are we in any sense of the word saved from this destruction. A philosophy, ideology, or religion which fails to touch the imagination fails in the end even to satisfy the reason.

In addition to poetry, Paisley also wrote plays, stories and some non-fiction, including an article on Naaman which was published in the ‘Evangelical Presbyterian’ in 1968. He sometimes used one of several pseudonymns; some work is signed Edward Penmore, Jon Darlo Gibealli, Albert Twimmon and Wilfred Penmore. It seems that he only ever had one commissioned piece, ‘Lord Jesus look on this we do’, a poem commissioned by the chaplain at Cherry Farm Hospital (a psychiatric hospital where John may have been a patient), and that that poem has since been set to music by Colin Gibson. From his teens onwards he struggled with mental illness, a condition which was ‘both serious and crippling’. He took his own life in 1984.

As I read the collection through to its end, I discovered a maturing poet and gentle human being, one who moves from an anxious obsession with answers to a deep fascination with and a journey into a vortex of questions, and into the incomprehensibility of human dreaming in search of love and of love’s end, of ‘a purpose [which] holds its ground’.

My plan is to post, over the next few weeks, a number of his poems here at PCaL. To that end, and to kick things off, here’s ‘Credo and Petition’:

I am tired of folly’s smiles,

Of false wax faces in the dizzy gallery,

The image and the paper mask.

And hollow is a chromium gilded heaven:

Hollow like unending, idle bliss beyond the grave.

Give me instead the fateful thunder of the clouds,

Barbed lightning, all that can destroy

And yet bring truth.

Who hourly holds aloft the burning sun

And comes so kindly bearing warmth and life?

He finds me struggling on the steps of my becoming

And shares with me the pain-wracked torturing

Of limbs upon the wooden world.

Of Him I ask now out of hope:

A weeping on the dark, mis-shapen stone of days bygone;

A stamping at the doorway of the beaten earth,

That paths may form and doors may open.

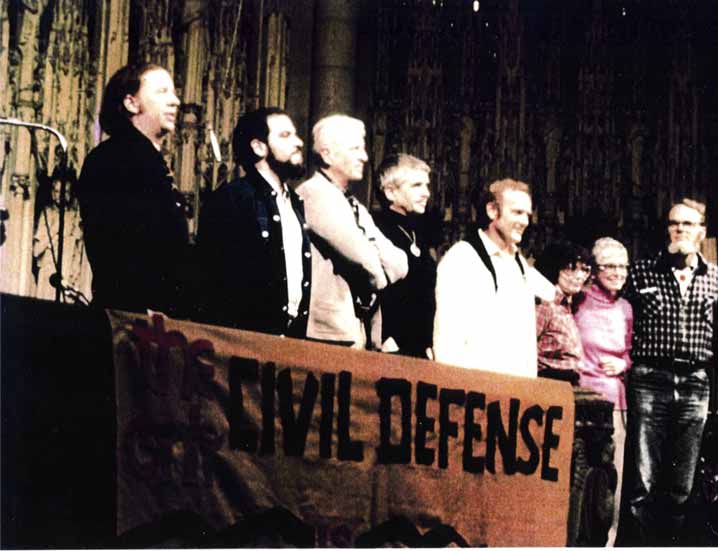

To the Plowshares 8, with love.

To the Plowshares 8, with love.