TITUS: Why is art important in times of crisis?

ME: I remember seeing an image of a bombed-out National Library in Sarajevo in 1992. Among the ruins was a man playing the cello. I later learnt that his name is Vedran Smailović, that he is a Bosnian musician and that he was playing a fragment of music rescued from the Saxon State Library in Dresden after it was bombed in 1945 by British and American Forces. I was struck by this simple human action and what it might suggest about the possibility of seeking and making meaning amid even the most horrific of circumstances.

Of course, sometimes there may not be meaning to be had at all. At other times, the horror is so great that it silences us, leaves our bodies immobile, sucks all meaning out of life, renders things like ‘art’ to be an impossible indulgence – or worse.

But in time, if indifference doesn’t get the better of us, there can arise the possibility to respond to crises in other registers. And here, I think, is where the artist and those who receive art recognise something about arts’ capacity to come near to the truth of things and the artist’s capacity to witness to dislocation in ways that refuse to accept that the way things appear is the way that things must be or will be. This is about committing to being human in a particular direction.

Another way of approaching all this is to think of art as a way of paying attention, which involves refusing to deny, or forget, or bury the most uncomfortable truths of the human experience. Simone Weil referred to such attention as ‘the rarest and purest form of generosity’.

It is, of course, about a way of dignifying the human condition. But it’s more than that. It’s also something about how art and imagination are closely associated with our hopes, imagination being a prerequisite for understanding and nurturing hope.

TITUS: How do these convictions find shape in this particular book, Imagination in an Age of Crisis, and who is it written for?

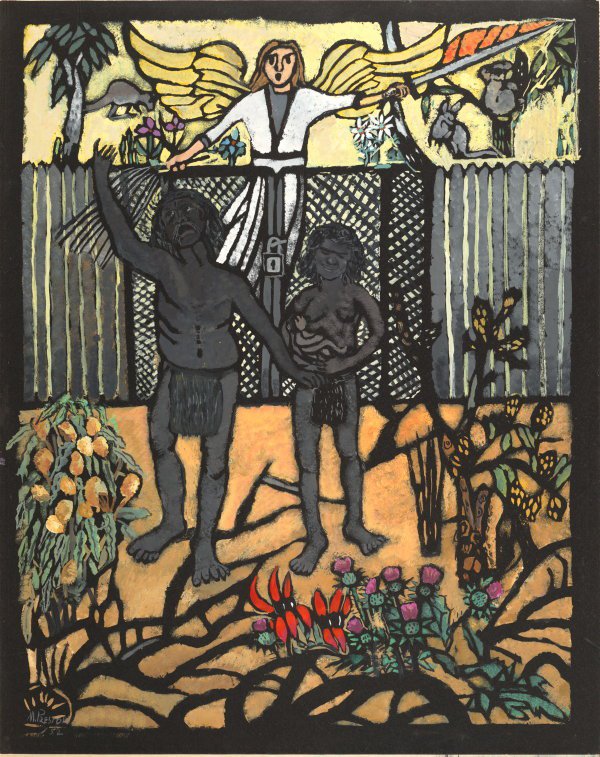

ME: This book is the work of a diverse group of over 30 poets, art practitioners, and academics reflecting together on how the arts and theology inform – and are informed by – our imaginations. They help us see and interpret what is happening in places such as an Aboriginal cooking ritual, biodiversity loss, institutional responses to child sexual abuse, folk rituals, our experience of film, theatre, music, and literature. Their contributions assist us to discern the ways of Spirit and generate hope and empathy in our lives.

Poets do that through attention to language and reverence for mystery. Art practitioners do that by working closely with the ‘stuff’ of meaning both before and after the limits of rationality. And theologians do that through engagement with cultural practices and products as possible modes of epiphany and witness. And the book offers some record about that.

The book is written for those open to the possibility of discovering wider horizons of meaning in a messy world. It is also written for artists willing to entertain the possibility that they are engaged in serious theological work. And it is for those who believe – or who want to believe – that art and spirituality can be acts of defiant hope in the face of all that appears anything but hopeful.

TITUS: Why does this book matter for theology?

ME: It seems that one of the things that good art does is to shed light on the true nature of things; it broadens our horizons, it enriches our capacity to see, it alerts us to dimensions of reality that we had not seen before, and for which regular prose, sometimes, is not enough. This is a helpful way to think also about the task of theology.

The other thing I’d want to say here is that both art and theology are concerned with how we receive gifts concerned with particular ways of knowing. These are often pursued on the wager that there is the possibility of something like an epiphany or a connection. At their best, they are also an invitation to say ‘Yes’ to engaging in conversations concerned with opening up matters in ways that resist the temptations to tie up loose threads. This is important because, very often, the truth of things seems to be hidden in these threads.

TITUS: Turning to the creation book, you could have chosen to work on a book on any number of topics, so why did you choose to devote time and energy to put together a book on creation?

ME: I’ve asked myself that question a lot over the past 7 years, and whenever I skim through an inbox of around 3,000 emails related to this book, representing something of the privilege and challenge of working with over 70 contributors from all over the globe.

The answer to the question of why is, of course, multi-faceted. But let me name just three things:

First, it arises from my conviction that theologians must be concerned with the most pressing issues of our time. Incontrovertibly, these include the threats posed to our ecosystem. At the same time, and for various reasons, we are increasingly dislocated from the world. Such matters ought to be of pressing concern to theologians and to the communities their work serves.

Second, I wanted to work on the kind of book I would find helpful as a student or as a teacher. This is one of the reasons the chapters tend to be quite short and avoid, wherever possible, copious technical paraphernalia. But more importantly, it’s why the book attends to so many different themes. I wanted to expose the assumptions that we all have about the created world and how these assumptions influence what we think about all kinds of other things – like beauty, land, justice, time, evil, the bible, medicine, sport, and technology – and then, conversely, how what we think about such things affects how we think about and live with creation.

Finally, there is something too about the place that doctrines of creation have typically played and continue to play in Christian thought. Typically, when it is on the radar at all – and it’s very often missing, especially in ecclesiocentric theologies – Christian accounts of creation treat the idea as a great unifying theme in which many other ideas coinhere. I think this is unfortunate, not only because such approaches inevitably flatten out the rich multiplicity of voices and ideas about creation in the bible and elsewhere but also because of how such accounts serve the agendas of the powerful. I hope that this volume, with its multiplicity of voices, methodologies, and themes, might challenge such approaches in ways that open up and deepen our love for and fascination about this world and for the entire creation beyond. Of course, it will be up to others to judge whether or not the volume has achieved these aims.