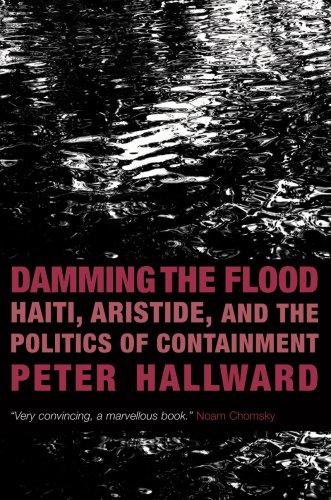

Back on 14 August 2008, Slavoj Žižek reviewed Peter Hallward’s Damming the Flood: Haiti, Aristide and the Politics of Containment, a review I thought worth reposting, particurlarly in light of recent tragedies effecting a country which otherwise hardly rates a mention in public discourse and the subsequent rhetoric of victimhood.

Back on 14 August 2008, Slavoj Žižek reviewed Peter Hallward’s Damming the Flood: Haiti, Aristide and the Politics of Containment, a review I thought worth reposting, particurlarly in light of recent tragedies effecting a country which otherwise hardly rates a mention in public discourse and the subsequent rhetoric of victimhood.

‘Noam Chomsky once noted that “it is only when the threat of popular participation is overcome that democratic forms can be safely contemplated”. He thereby pointed at the “passivising” core of parliamentary democracy, which makes it incompatible with the direct political self- organisation and self-empowerment of the people. Direct colonial aggression or military assault are not the only ways of pacifying a “hostile” population: so long as they are backed up by sufficient levels of coercive force, international “stabilisation” missions can overcome the threat of popular participation through the apparently less abrasive tactics of “democracy promotion”, “humanitarian intervention” and the “protection of human rights”.

This is what makes the case of Haiti so exemplary. As Peter Hallward writes in Damming the Flood, a detailed account of the “democratic containment” of Haiti’s radical politics in the past two decades, “never have the well-worn tactics of ‘democracy promotion’ been applied with more devastating effect than in Haiti between 2000 and 2004”. One cannot miss the irony of the fact that the name of the emancipatory political movement which suffered this international pressure is Lavalas, or “flood” in Creole: it is the flood of the expropriated who overflow the gated communities that protect those who exploit them. This is why the title of Hallward’s book is quite appropriate, inscribing the events in Haiti into the global tendency of new dams and walls that have been popping out everywhere since 11 September 2001, confronting us with the inner truth of “globalisation”, the underlying lines of division which sustain it.

Haiti was an exception from the very beginning, from its revolutionary fight against slavery, which ended in independence in January 1804. “Only in Haiti,” Hallward notes, “was the declaration of human freedom universally consistent. Only in Haiti was this declaration sustained at all costs, in direct opposition to the social order and economic logic of the day.” For this reason, “there is no single event in the whole of modern history whose implications were more threatening to the dominant global order of things”. The Haitian Revolution truly deserves the title of repetition of the French Revolution: led by Toussaint ‘Ouverture, it was clearly “ahead of his time”, “premature” and doomed to fail, yet, precisely as such, it was perhaps even more of an event than the French Revolution itself. It was the first time that an enslaved population rebelled not as a way of returning to their pre-colonial “roots”, but on behalf of universal principles of freedom and equality. And a sign of the Jacobins’ authenticity is that they quickly recognised the slaves’ uprising – the black delegation from Haiti was enthusiastically received in the National Assembly in Paris. (As you might expect, things changed after Thermidor; in 1801 Napoleon sent a huge expeditionary force to try to regain control of the colony).

Denounced by Talleyrand as “a horrible spectacle for all white nations”, the “mere existence of an independent Haiti” was itself an intolerable threat to the slave-owning status quo. Haiti thus had to be made an exemplary case of economic failure, to dissuade other countries from taking the same path. The price – the literal price – for the “premature” independence was truly extortionate: after two decades of embargo, France, the old colonial master, established trade and diplomatic relations only in 1825, after forcing the Haitian government to pay 150 million francs as “compensation” for the loss of its slaves. This sum, roughly equal to the French annual budget at the time, was later reduced to 90 million, but it continued to be a heavy drain on Haitian resources: at the end of the 19th century, Haiti’s payments to France consumed roughly 80 per cent of the national budget, and the last instalment was only paid in 1947. When, in 2003, in anticipation of the bicentenary of national independence, the Lavalas president Jean-Baptiste Aristide demanded that France return this extorted money, his claim was flatly rejected by a French commission (led, ironically, by Régis Debray). At a time when some US liberals ponder the possibility of reimbursing black Americans for slavery, Haiti’s demand to be reimbursed for the tremendous sum the former slaves had to pay to have their freedom recognised has been largely ignored by liberal opinion, even if the extortion here was double: the slaves were first exploited, and then had to pay for the recognition of their hard-won freedom.

The story goes on today. The Lavalas movement has won every free presidential election since 1990, but it has twice been the victim of US-sponsored military coups. Lavalas is a unique combination: a political agent which won state power through free elections, but which all the way through maintained its roots in organs of local popular democracy, of people’s direct self-organisation. Although the “free press” dominated by its enemies was never obstructed, although violent protests that threatened the stability of the legal government were fully tolerated, the Lavalas government was routinely demonised in the international press as exceptionally violent and corrupt. The goal of the US and its allies France and Canada was to impose on Haiti a “normal” democracy – a democracy which would not touch the economic power of the narrow elite; they were well aware that, if it is to function in this way, democracy has to cut its links with direct popular self-organisation.

It is interesting to note that this US-French co-operation took place soon after the public discord about the 2003 attack on Iraq, and was quite appropriately celebrated as the reaffirmation of their basic alliance that underpins the occasional conflicts. Even Brazil’s Lula condoned the 2004 overthrow of Aristide. An unholy alliance was thus put together to discredit the Lavalas government as a form of mob rule that threatened human rights, and President Aristide as a power-mad fundamentalist dictator – an alliance ranging from ex-military death squads and US-sponsored “democratic fronts” to humanitarian NGOs and even some “radical left” organisations which, financed by the US, enthusiastically denounced Aristide’s “capitulation” to the IMF. Aristide himself provided a perspicuous characterisation of this overlapping between radical left and liberal right: “Somewhere, somehow, there’s a little secret satisfaction, perhaps an unconscious satisfaction, in saying things that powerful white people want you to say.”

The Lavalas struggle is exemplary of a principled heroism that confronts the limitations of what can be done today. Lavalas activists didn’t withdraw into the interstices of state power and “resist” from a safe distance, they heroically assumed state power, well aware that they were taking power in the most unfavourable circumstances, when all the trends of capitalist “modernisation” and “structural readjustment”, but also of the postmodern left, were against them. Constrained by the measures imposed by the US and International Monetary Fund, which were destined to enact “necessary structural readjustments”, Aristide pursued a politics of small and precise pragmatic measures (building schools and hospitals, creating infrastructure, raising minimum wages) while encouraging the active political mobilisation of the people in direct confrontation with their most immediate foes – the army and its paramilitary auxiliaries.

The single most controversial thing about Aristide, the thing that earned him comparisons with Sendero Luminoso and Pol Pot, was his pointed refusal to condemn measures taken by the people to defend themselves against military or paramilitary assault, an assault that had decimated the popular movement for decades. On a couple of occasions back in 1991, Aristide appeared to condone recourse to the most notorious of these measures, known locally as “Père Lebrun”, a variant of the practice of “necklacing” adopted by anti-apartheid partisans in South Africa – killing a police assassin or an informer with a burning tyre. In a speech on 4 August 1991, he advised an enthusiastic crowd to remember “when to use [Père Lebrun], and where to use it”, while reminding them that “you may never use it again in a state where law prevails”.

Later, liberal critics sought to draw a parallel between the so-called chimères, ie, members of Lavalas self-defence groups, and the Tontons Macoutes, the notoriously murderous gangs of the Duvalier dictatorship. The fact that there is no numerical basis for comparison of levels of political violence under Aristide and under Duvalier is not allowed to get in the way of the essential political point. Asked about these chimères, Aristide points out that “the very word says it all. Chimères are people who are impoverished, who live in a state of profound insecurity and chronic unemployment. They are the victims of structural injustice, of systematic social violence [. . .] It’s not surprising that they should confront those who have always benefited from this same social violence.”

Arguably, the very rare acts of popular self- defence committed by Lavalas partisans are examples of what Walter Benjamin called “divine violence”: they should be located “beyond good and evil”, in a kind of politico-religious suspension of the ethical. Although we are dealing with what can only appear as “immoral” acts of killing, one has no political right to condemn them, because they are a response to years, centuries even, of systematic state and economic violence and exploitation.

As Aristide himself puts it: “It is better to be wrong with the people than to be right against the people.” Despite some all-too-obvious mistakes, the Lavalas regime was in effect one of the figures of how “dictatorship of the proletariat” might look today: while pragmatically engaging in some externally imposed compromises, it always remained faithful to its “base”, to the crowd of ordinary dispossessed people, speaking on their behalf, not “representing” them but directly relying on their local self-organisations. Although respecting the democratic rules, Lavalas made it clear that the electoral struggle is not where things are decided: what is much more crucial is the effort to supplement democracy with the direct political self-organisation of the oppressed. Or, to put it in our “postmodern” terms: the struggle between Lavalas and the capitalist-military elite in Haiti is a case of genuine antagonism, an antagonism which cannot be contained within the frame of parliamentary-democratic “agonistic pluralism”.

This is why Hallward’s outstanding book is not just about Haiti, but about what it means to be a “leftist” today: ask a leftist how he stands towards Aristide, and it will be immediately clear if he is a partisan of radical emancipation or merely a humanitarian liberal who wants “globalisation with a human face”‘.

[Source: New Statesman]

For those who may wish to do more than just read an old book review, here’s a wee list of (mostly American) groups seeking to respond to the needs of Haitians at the moment, all of whom would be pleased to have your support:

And for those of us who pray, Rose Marie Berger has penned the following ‘Prayer for Haiti (January 2010)’ to help us:

Most Holy Creator God, Lord of heaven and earth,

we bring before you today your people of Haiti.

It is you who set in motion the stars and seas, you who

raised up the mountains of the Massif de la Hotte and Pic La Selle.

It is you who made her people in your very image:

Their gregarious hearts, generous spirits,

their hunger and thirst for righteousness and liberty.

It is you, O Lord, who planted the rhythms of konpa, Twoubadou,

and zouk in the streets of Cite-Soleil. You who walk the paths

outside of Jacmel and Hinche. Your people, O Lord, cry out to you.

Haiti, O Haiti: the world’s oldest black republic,

the second-oldest republic in the Western world.

You are a God who answers the cries of the suffering.

You are a God who sees, frees, and redeems your people.

“I too have heard the moaning of my people,” you spoke to Moses. Now, Lord, speak to Chanté, Agwe, Nadege, and Jean Joseph.

Speak now, O Lord, and comfort Antoine, Jean-Baptiste,

Toto, and Djakout. Raise up your people from the ash heap

of destruction and give them strong hearts and hands,

shore up their minds and spirits. Help them to bear this new burden.

As for us, Lord, we who are far away from the rubble and the dust, the sobbing and the moans, but who hold them close in our hearts, embue us with the strength of Simon the Cyrene.

Help us to carry the Haitian cross; show us how to lighten the yoke with our prayers, our aid, our resources. Teach us to work harder

for justice in our own country and dignity in Haiti,

so that we may stand with integrity when we hold our Haitian families in our arms once again. We ask this in the name of Jezikri, Jesus Christ. Amen.

Since the birth of his daughter Aurora, Byron Smith has been posting some great little reflections on baptism, on whether to dunk, dip, douse or dribble?, and his latest on timing and why parents should not wait:

Since the birth of his daughter Aurora, Byron Smith has been posting some great little reflections on baptism, on whether to dunk, dip, douse or dribble?, and his latest on timing and why parents should not wait:

‘Like most preachers, I grossly overestimated the importance of my part in the sermon. When I thought of preaching, I did not consider it to be a congregation’s reception of the word of God, but a speaker’s command of the Bible’s hidden meanings and applications, which were served up in a way to showcase the authority and skill of the preacher. In those days the gospel lived or died by my personal performance. My preaching was a small cloud of glory that followed me around and hung like a canopy over the pulpit whenever I occupied it. How ludicrous I must have appeared to my congregation.

‘Like most preachers, I grossly overestimated the importance of my part in the sermon. When I thought of preaching, I did not consider it to be a congregation’s reception of the word of God, but a speaker’s command of the Bible’s hidden meanings and applications, which were served up in a way to showcase the authority and skill of the preacher. In those days the gospel lived or died by my personal performance. My preaching was a small cloud of glory that followed me around and hung like a canopy over the pulpit whenever I occupied it. How ludicrous I must have appeared to my congregation.