In my most recent post in this series, I made the claim that to engage in Christian ministry is to take up an invitation to participate in the life of God. Indeed, it is to enter into God’s rest. To enter such rest is to be, in Irenaeus’ words, ‘fully alive’. More wonderfully, it is to be ‘the Glory of God’. In this post I wish to ruminate on the Decalogue’s fourth word; namely, that which concerns the grace of Sabbath, the rest which renews and restores:

In my most recent post in this series, I made the claim that to engage in Christian ministry is to take up an invitation to participate in the life of God. Indeed, it is to enter into God’s rest. To enter such rest is to be, in Irenaeus’ words, ‘fully alive’. More wonderfully, it is to be ‘the Glory of God’. In this post I wish to ruminate on the Decalogue’s fourth word; namely, that which concerns the grace of Sabbath, the rest which renews and restores:

‘Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. 10 But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work – you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it’. (Exod 20.8–11)

Whereas the First Word is about how we honour God with our loyalty, the Second about how we honour God with our thought life, the Third about how we honour God with our words, this Fourth Word concerns how we honour God with our time. This word has nothing at all to do with legalistic notions associated with various brands of Sabbatarianism. It does have everything to do with rest and with God’s invitation that we enter his rest. This word is all about the use of our time in a rhythm of toil and rest, work and worship. It reminds us that the goal of God’s creation is not humanity, but Sabbath. And unlike the other six days, the seventh day has no end. In other words, we live in the Sabbath now. The Sabbath of God is the whole history of the world from the sixth day until the end (of time).

Few commandments in holy writ so cut across the grain of Western society as this one. In his book, The Soul of Ministry: Forming Leaders for God’s People, Ray Anderson devotes an entire chapter to the matter of Sabbath. He speaks of the ‘slave master self’ that lurks at the edges of the human psyche. Whether it be a demanding parent or boss or job, like Israel we too carry this virus with us – a ‘hidden virus with an insatiable appetite for healthy flesh’ (p. 60). While Israel had just been redeemed from a dehumanising bondage in Egypt, they were yet to be redeemed from the bondage that existed in their very being. And so not only would they need to learn ‘the discipline of the Sabbath’ for their own well-being, but they would also need to learn ‘the theology of the Sabbath’ in order to strengthen their faith and to give perspective to their hope.

Anderson writes:

‘Without a theology of the Sabbath, the discipline of the Sabbath would itself become a slave master as, in fact, quickly happened. By the time of Jesus, the Sabbath discipline had become a law more severe and sacred than any moral imperative. Paradoxically, liberation from the taskmaster of the sabbath law was a primary occasion for the condemnation and execution of Jesus. That which was to be a sacrament of liberation, of renewal and restoration, had become a rigid and inhumane rule from which liberation was effected by the ministry of Jesus!’

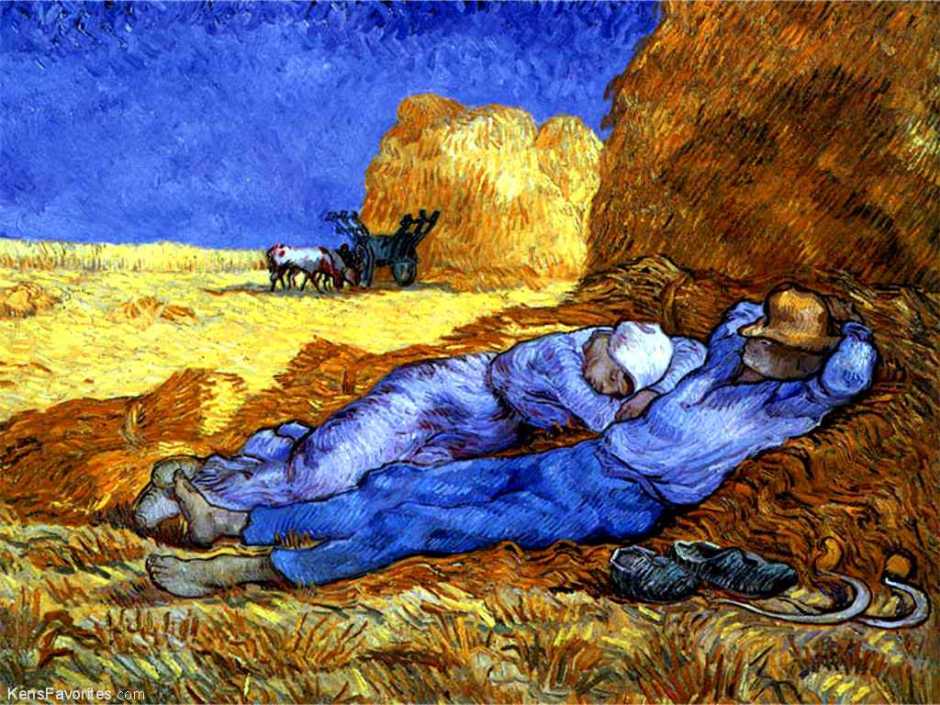

Sabbath is not about taking a ‘day-off’ – what Eugene Peterson calls ‘a bastard Sabbath’ (in Working the Angles: The Shape of Pastoral Integrity, p. 66); rather it is a conscious effort of entering into, and responding to, the rhythms and actions of Spirit at work in creation. It is realising that God is not waiting for us to wake up to begin working each day, but that God is working already and inviting us, when we awake, firstly to listen, and only then to join in.

Sabbath time is not a time that proves its worth or justifies itself. It is not a time to ‘get things done’. It is a time of rest, of ‘not-doing’. No Patmos visions. No Sinai’s. No Mounts of Transfiguration. It is, put simply, the sanctification of time.

Thinking about Sabbath recalls that the Sabbath was God’s way of operating before it became ours. (Geoffrey Bingham’s The Law of Eternal Delight is helpful here). So Genesis 1.31–2.3:

‘God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day. Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their multitude. And on the seventh day God finished the work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all the work that he had done. So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work that he had done in creation’.

There is no commandment here for us concerning what we should do with this day. What there is is a sense of completeness. On the seventh day – not at the end of the sixth day – God stopped creating. But that does not mean that God is finished working. Rather, God keeps on sustaining and providing for his creation. God is, in every sense, ‘the faithful Creator’ (1 Pet 4.19).

The other thing that Genesis 1 and 2 highlight is that the goal of God’s creation is not humanity but Sabbath. Creation was not finished until God made the Sabbath. The seventh day was not God’s day off. It was the day God finished creating and rested. Also, unlike the other six days, the seventh day has no end. When we read through Genesis 1 we notice a rhythm: ‘And God said … and there was evening and there was morning, the first day. And God said, … and there was evening and there was morning, the second day … the third day … the fourth day … the fifth day … the sixth day’. But when we get to the seventh day there is no end because the seventh day is all the history of the world from the end of the sixth day until the end of time itself. In other words, we are living in the seventh day now. This is what we were made for – to enter into God’s rest.

And what was creation’s seventh day was, for the primal couple, only their second. Might it not be significant that immediately after creating them God thrust them into his rest? Might it not be that the reason that there remains a Sabbath-rest for the people of God (Heb 4.9) is precisely because we are those who live in God’s own rest; i.e., in God’s finished work in creation and redemption. The people of God are those who take seriously Jesus’ cry ‘It is finished’ and live in the truth that we have no rest apart from that in the crucified and risen Lamb! Jesus Christ is our Sabbath rest!

Sabbath makes no sense apart from its relationship to the creation, and to the covenant that God has made with creation. It is little surprise then that it is the only one of the Ten Words that finds its voice in the creation narratives, completing both the creation itself, and marking the beginning of creation’s growth and renewal by God. We might also note here that the Sabbath command was revealed to Israel in hard-copy form at Sinai before they set down to write the creation account. In other words, Genesis makes most sense (and matters most) because Exodus has happened. Only in this order – redemption then creation – is the theo-logic of the Fourth Word preserved. This recalls not only that redemption and creation are interwoven, but also that Israel already had a theology of redemption and creation before they had a theology of the Fall, sin and death.

The second creation account reads: ‘Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their multitude. And on the seventh day God finished the work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all the work that he had done’ (Gen 2.1–2). On these verses, Anderson notes: ‘The sixth day represents the culmination of creaturely possibility, while the seventh day represents the possibility and creative conclusion that God provides. A theology of the Sabbath, therefore, is a theology of God’s Sabbath ministry of completion of his work. This is the ministry of renewal and restoration’ (pp. 62–3).

In the Book of Hebrews, the author understands the Sabbath rest as synonymous with the Israelites journey from slavery to liberation, from a land of mud and whips to that ‘flowing with milk and honey’ (Exod 3.8, 17; 13.5; 33.3). The author describes entry into this land of promise as ‘entering into God’s rest’ (Heb 3.11, 18; 4.3), identifying this entering by citing the second creation account in Genesis (Heb 4.4; Gen 2.2). The author of Hebrews suggests that the redeemed Israelites failed to enter into this rest because of their disobedience. Thus the invitation to enter into the rest remains: ‘So then, a sabbath rest still remains for the people of God; for those who enter God’s rest also cease from their labors as God did from his’ (Heb 4.9–10).

Anderson notes that ‘the Sabbath rest of God can be understood as the continuing ministry of God “completing his work” on the seventh day. The seventh day is the end of the sixth day. This end goal represents the last or final work of God. The seventh day, therefore, provides an end-goal orientation for the sixth day. As the ‘last day’, the seventh day now casts its light back into the sixth day, the next to the last day’ (p. 63). Recalling Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Anderson reminds us that while the last day is the ultimate, the next to the last is the penultimate. It is the ultimate (the seventh day) that gives meaning to the penultimate (the sixth day). In other words, today makes sense because of tomorrow. Furthermore, tomorrow does not eliminate the significance of today so much as provide a proper context, dignity and perspective for the environment in with earthly existence is lived out and apart from which the six days would seem pointless and endless. ‘Anticipation of the seventh day, even from the first day of the week, makes what would otherwise be unbearable something that can be accepted as having only limited power and duration’ (p. 63).

The Sabbath requirement also reminds us that there is more to life than work. This is not because work is a bad thing – indeed, work is just as ‘holy’ as rest from it – but the Sabbath was given to (in)form the usage of all our time. In Deuteronomy 5, the reason given for Sabbath-keeping is that our ancestors in Egypt went for something like 400 years without rest. Under Egyptian slavery they were compelled to work – they never had a day off. They were considered slaves, not people. Hands, work units for building bricks for shrines of death. And so when they were redeemed they were released into a rest that had eluded them for hundreds of years. Their Sabbath was identified with their salvation. That is why, it seems to me, that as part of the Sabbath they were not only to rest but to celebrate their redemption. And not only them but also their servants and their livestock and the sojourners among them. This was a gift to the whole covenant community because when God brings us out of bondage he frees us so we are no longer slaves to our work. So Jesus’ words: ‘Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light’ (Matt 11.28–30). Jesus comes into our sixth day with the invitation, ‘come with me into my own Sabbath rest’.

So we given a glimpse here into the truth that the Sabbath is God’s grace gift for all round renewal. We were not created to be at it all the time, to be slaves to our work, or to our egos, or to a day. Remembering the Sabbath day, therefore, has to do with trusting in Christ whether or not we make or break the day. It has to do with trusting that Christ is working on the Sabbath in our place. It has to do with the liberating reality that this world does not revolve around us and what we are doing. It has to do with saying ‘Yes’ to Jesus’ invitation to come and enter into his rest. It has to do with making a conscious effort of entering into and responding to the rhythms and actions of the God who is always at work. It has to do with God’s work of bringing humanity into his rest. It has to do with God ‘finishing’ his ancient work of renewal and restoration and healing and liberation from oppression and sin and abuse and injustice and all else that restricts human flourishing. That is where the Pharisees got it so wrong and Jesus got it so right (see Matthew 12.1–13 and John 5.1–18). Jesus was accused of ‘working’ on the Sabbath. Of course he was working on the Sabbath! What else would God be doing on the Sabbath but healing and liberating a groaning creation from the bondage of the sixth day and bringing it into the very rest that it was all created for!

The fourth commandment is not given to bind us up in legalistic knots. It is given so that we might not be slaves anymore to anything, but rather we might enjoy our won-freedom and rest in God. It is given that we might not try to live as though God does not exist. It is given that we might participate in the ministry and rest of Jesus. In other words, it is an invitation to trust in One who watches over us, who neither slumbers nor sleeps, and who works for us. So Matthew 6.25–34:

‘Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds of the air; they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? And can any of you by worrying add a single hour to your span of life? 28 And why do you worry about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you – you of little faith? Therefore do not worry, saying, “What will we eat?’ or “What will we drink?’ or “What will we wear?’ For it is the Gentiles who strive for all these things; and indeed your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. But strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. “So do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today’s trouble is enough for today’.

Jesus’ work as the Incarnate Son takes place during the sixth day and is done with a view of bringing to completion the creation which he began as the Word of God. Thus he taught that ‘the Sabbath was made for humankind, not humankind for the Sabbath’, and that ‘the Son of Man is lord even of the Sabbath’ (Mark 2.27–28). Through the Spirit, the Son of Man continues the Father’s work of healing, restoring, liberating, comforting, forgiving not only on the sixth day, but also on the Sabbath. By doing this, the ‘lord of the Sabbath’ is setting a precedent that ought to find expression in every day of the week. (See, for e.g., Rom 14.5–6; cf. Col 2.16).

Anderson writes:

‘The original consecration of the seventh day as the Sabbath left the other six days unconsecrated, as it were. Only on the evening of the sixth day could the Israelite stand with his or her back to these days and step into the day consecrated by the renewal and restoration of the Lord. On this day they were to celebrate life as a gift of Yahweh, with no efforts of their own needed beyond the necessary chores. The point was that they were to leave behind the struggle to live by their own efforts and live out of the gracious provision of God. Those who attempted to carry over into this consecrated day some tasks related to their own purpose were severely judged. Some were even put to death for this violation. Even so small a matter as gathering sticks for the fire on the Sabbath caused the death of one man (Num 15:32–36). The enormity of the violation was not determined by the scale of the incident, but because it served to undermine the entire fabric of the covenant grounded in grace alone. The ‘slave driver’ within must be exposed and removed before we can experience the full deliverance of our humanity from bondage. Grace does not stop with the removal of external conditions of oppression and pain, but seeks deep inner healing and recovery’. (pp. 64–5)

Through their disobedience, the primal couple fell out of the rest that was given to them to enjoy. As a consequence, their death became sealed with that of the sixth day. The Sabbath, therefore, served as a ‘sacramental bridging of this abyss’ (p. 65) which offered immediate relief from nature’s powers and the threat of death. While the six days would always be lived under these powers, the seventh day provided relief, renewal, and restoration that pointed towards a final jubilee and the hope of the reconciliation of all things to God. Saint Paul also witnesses to something of this:

‘For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God’ (Rom 8.19–21).

This setting free happens in and through Jesus Christ who in his incarnation entered into the nothingness and dread of human depravity in order to bring creation into the saving rest of God. The Bible’s word for this action is ‘grace’. Grace is never a soft thing. Grace is a man groaning on a cross, dying on a bitter tree, not only for his friends but also for those who would wish him and his Father dead. Grace is God redeeming in holy love. Grace is God in his eucatastrophic action in the face of Nature’s catastrophe. Grace is God taking seriously the scandalous nature of sin’s offence, and himself going down into the experience of nothingness and dread, into hell, into death, into the furnace of his own wrath, into the radical depths of its wound, in order to save. There can be no higher gift. This grace alone, the grace of the initiating Father, lived in the obedient Son, and made alive through the Spirit, carries humanity home and brings creation into the Sabbath rest of God. Only then can Paul sing: ‘For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord’ (Rom 8.38–39).

Now the ‘Lord who is the Sabbath’ calls us into his rest in order that we might join him in doing the things that he is doing ‘on the Sabbath’ every day of the week. There can be no place here for that Sabbatarianism that consecrates one day out of all the others. In Christ, every day is about Sabbath rest, renewal and healing, that our entire ministry may be performed under the grace-aegis of God. To keep the Sabbath is never about conformity to rules and regulations (Col 2.22), but is about conformity to Christ who is the Lord of the Sabbath.

I conclude this post with a wee poem that I penned recently. It is titled ‘Sabbath’:

Sabbath means

living with limits –

with the limits of time: of millennia, of centuries, of minutes and of seconds,

with the limits of creatureliness,

with the limits of creation itself,

with the limits of knowing.

Sabbath means

living with faith –

faith in the muscle of ancient and unbroken promises,

faith in the magic of rest,

faith in the remorselessness of Love’s ongoing endeavour;

Wendell Barry is right: ‘Great work is done while we’re asleep’.

Sabbath means

living with hope –

hope that the deepest reality and creation’s flourishing do not revolve around me,

hope in the renewing power of stillness,

hope that both pools and rapids (in)form the life of the one river,

hope that a community – whose roots are long and deep, and whose shoots recur fresh and green – has heard rightly.

Sabbath means

living with love –

love of one’s self and of one’s other,

love of election to vocation,

love of the law of eternal delight,

love of what is,

and love of the other days, for ‘the Sabbath cannot survive in exile, a lonely stranger among days of profanity’ (Abraham Heschel).

© Jason Goroncy,

2 September 2010

Bannockburn

◊◊◊

Other posts in this series:

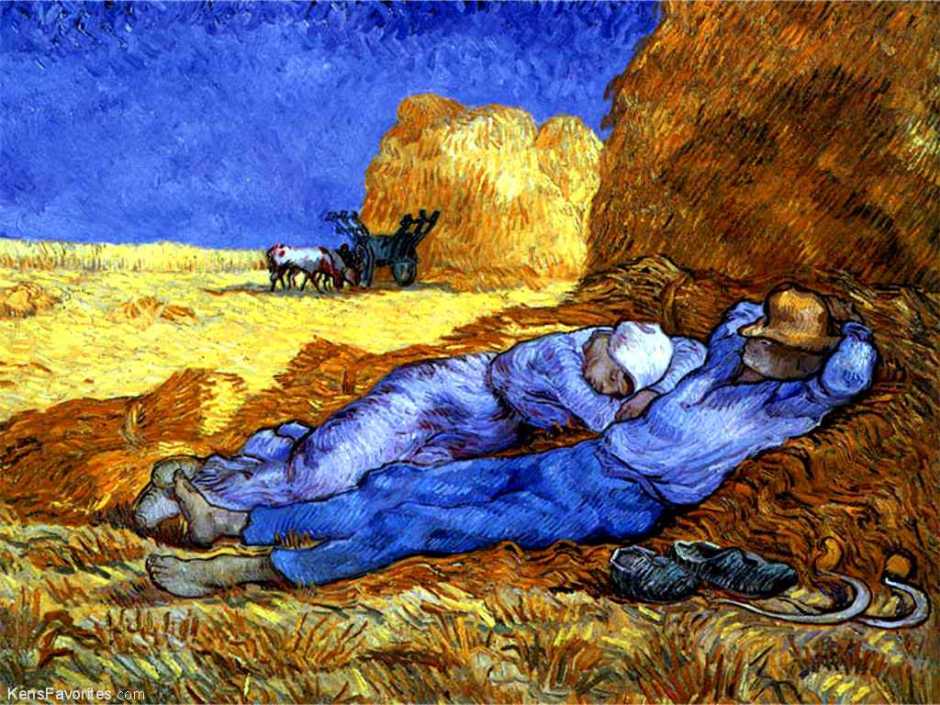

[Image: Vincent van Gogh, ‘Noon: Rest From Work (After Millet)’. 1889–90; Musée d’Orsay, Paris]

January 2011 will witness Professor Bruce McCormack give the Croall Lectures (in the Martin Hall at New College) on the theme ‘Abandoned by God: The Death of Christ in Systematic, Historical, and Exegetical Perspective’. The titles are:

January 2011 will witness Professor Bruce McCormack give the Croall Lectures (in the Martin Hall at New College) on the theme ‘Abandoned by God: The Death of Christ in Systematic, Historical, and Exegetical Perspective’. The titles are: