David Clough is a very fine Christian theologian who for many years now has been doing some great work to help us rethink our attitude to animals. Recently, he delivered a wonderful inaugural professorial lecture at The University of Chester (a university, to be sure, with some aesthetically-challenged lecture rooms) on the subject ‘Rethinking Animality: Towards a New Animal Ethics’, or Why Christians (& others) should stop eating animals from intensive farming. I thought it was worth sharing, so here it is:

Author: Jason Goroncy

Alan Sell’s The Theological Education of the Ministry: Soundings in the British Reformed and Dissenting Traditions: a review

Alan P. F. Sell, The Theological Education of the Ministry: Soundings in the British Reformed and Dissenting Traditions (Eugene, OR.: Pickwick Publications, 2013). ISBN 13: 978-1-62032-593-3; 328pp.

Alan P. F. Sell, The Theological Education of the Ministry: Soundings in the British Reformed and Dissenting Traditions (Eugene, OR.: Pickwick Publications, 2013). ISBN 13: 978-1-62032-593-3; 328pp.

A guest review by Graeme Ferguson

Alan Sell, who served for a time as Theological Secretary of the WARC and who taught in Manchester and Wales, has indulged himself in retirement, writing a very readable account of the thinking of several theologians who helped form ministry in the reformed tradition in Great Britain and whose contribution should not be forgotten.

It may come as a surprise that the English dissenting tradition is as angular and stubborn today as it has been through the years in shaping the Church. Sell, as an unrepentant Congregationalist, knows the ins and outs of this history well. He has worked with the theologians who shaped ministry in the last fifty years. He has the patience to track through some of the more tortuous paths of dissent both in England and Scotland and celebrates several churchmen who are not widely remembered.

He begins with Caleb Ashworth and the dissenting academy he set up in Daventry. This sets the tone for remembering the costs involved in bearing witness to the faith outside the mainstream of English church life.

His chapter on Scottish religious philosophy in the later nineteenth century is a sharp reminder of how effectively and fully Scottish theologians engaged in the intellectual debates of the day. Theological professors such as A.C. Fraser, Robert Flint, A.B. Bruce, James Iverach, and others, came out of the realist tradition of the Scottish Enlightenment. They were committed apologists for the faith, formulating forms of knowing that gave an assured intellectual basis for strong faith. Their books were found on the shelves of many New Zealand ministers who followed these debates closely.

His chapter on John Oman of Cambridge not only traces his formidable philosophical contribution to personalist modes of knowing God but also has a fascinating segment on Oman’s church background in the secessionist groups of the islands of northern Scotland. Oman is an Orcadian who for all his life retained that mystical spirituality of the northern lights. I was glad to see that Sell added the story about Oman’s portrait which hangs in the dining hall at Westminister College. One person asked the artist if the sitter’s face was that of a fisherman; another suggested a philosopher, and a third that he had the face of a saint. The artist was content that he had captured Oman’s heart.

In writing about N.H.G. Robinson and Geoffrey Nuttall, Sell speaks about people he knew and valued. Robinson was an ethicist in St Andrews, a careful scholar committed to clarity and precision in developing his ideas. Sell develops a set of theses to encapsulate Robinson’s thinking. Nuttall was an angular and difficult church historian of English dissent who taught in London and with whom Sell had a long friendship. Not only did Nuttall not suffer fools, but he was also an authority on Puritanism and dissent. Both men influenced a generation of students to value sound scholarship and appreciate the richness and depth of lively faith.

This book needed some strong editing. In trying to ensure that each scholar could speak for himself, Sell quotes extensively. There are some personal interjections which may be endearing but which read as self-justifying. A good editor would have picked up infelicities of language and dates that wobbled into the wrong century. Also, the bibliographies are far too long. But the book was well worth persevering with as a fascinating study of people, with their foibles, personal loves and hates, and passion for sound scholarship, who influenced generations of people serving in ministry.

The United Stasi of America – championing a new level of efficiency

‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks’. – The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 12.

‘After the Wall fell the German media called East Germany “the most perfected surveillance state of all time”. At the end, the Stasi had 97,000 employees – more than enough to oversee a country of seventeen million people. But it also had over 173,000 informers among the population. In Hitler’s Third Reich it is estimated that there was one Gestapo agent for every 2,000 citizens, and in Stalin’s USSR there was one KGB agent for every 5,830 people. In the GDR, there was one Stasi officer or informant for every sixty-three people. If part-time informers [many of whom were ‘pastors’] are included, some estimates have the ratio as high as one informer for every 6.5 citizens’. – Anna Funder, Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall, p. 57.

Having recently finished reading Funder’s wonderful book, it has been near impossible to not observe some very disturbing parallels with what is unfolding about PRISM. Today, we face a situation where something towards 39% of the world’s population (or something in the order of 2.5 billion people) – which is the number of the world’s internet users – can be spied on by a single person/agency. Just as terrifying is the fact that he who has informed ‘the people’ about this situation is labeled a ‘traitor’, though to what exactly is not too clear.

The shareholders will, no doubt, rejoice at news of such unprecedented levels of efficiency and technological sophistication, and in the assurances that their ‘interests’ are being maintained at all costs. Most important, though, is that Edward Snowden’s girlfriend is doing ok. Ah, all’s well with the world Empire!

…

Tonight, I will go to bed with Václav Havel and Dietrich Bonhoeffer; they help me at such times. And in the morning, I will (God willing) awake into a world that belongs to One upon whose word I will meditate, and to whom I shall direct my gaze and the burdens of the world and of things closer to my own soul. Ah, He is risen. All is indeed well with the world! Optimism? No. An opiate? No one who has ever really prayed has ever thought so, and I trust them. Patience and hope? Yes. And so joy.

The Tendering of New Zealand’s Restorative Justice Services: Robbing Peter to Pay Paul

A guest post by Janet Sim Elder

The recent announcement that government tendering of Restorative Justice (RJ) services throughout Aotearoa New Zealand to a smaller number of providers based here in NZ or from offshore is imminent. Judith Collins, Minister of Justice, has also announced there an increase of funding of $4.42 million in the May budget. Clearly this National Government wants to expand services.

A good thing you might say. Yes it is, but … and there is a large ‘but’. Ministry staff numbers entrusted with servicing the Restorative Justice groups around the country have gradually diminished over the last thirteen years since we in Dunedin and three other jurisdictions trained and were part of the world-first pilot of RJ as an alternative way of doing justice within the Justice system.

From a vibrant, forward-thinking, large group of public servants, the staff in this unit now number about five. The logic is, I suspect, that it is much easier and more cost efficient for a small group of Ministry staff to work with a handful of providers; the fewer the better.

Restorative Justice Aotearoa, the national grouping of all RJ services in NZ, is not in a position to put in a tender for all those services and is clearly not interested in doing so.

Nicola Taylor, the feisty Director of Anglican Family Care in Dunedin under whose umbrella we work as Restorative Justice Otago, providing long-term, highly professional and skilled work in bringing victims and offenders together to hear each other’s stories and to begin repair of the harms caused by offending, has decided we have no other option than to submit a tender ourselves. It’s risky because we have no certainty we will be successful, and because there is no contingency plan if we fail. Our story will be replicated throughout the country for the other RJ providers.

So we are committed to going all out for a strong bid to provide services in our Otago region. We have a depth and breadth of experience and are known and trusted by victims and offenders alike, as well as by local professionals working within and around the court system. This all has to be done in a few short weeks rather than months. Anglican Family Care is committing resources including in governance and making tenders to ensure we put in the best tender we can.

So we are committed to going all out for a strong bid to provide services in our Otago region. We have a depth and breadth of experience and are known and trusted by victims and offenders alike, as well as by local professionals working within and around the court system. This all has to be done in a few short weeks rather than months. Anglican Family Care is committing resources including in governance and making tenders to ensure we put in the best tender we can.

If you can help with brief letters of support for our bid, or for the RJ group near you elsewhere in the country in the same boat as we are, then, who knows, Peter does not have to be robbed in order to pay Paul and both might have a chance to live life in all its fullness!

To help out, please contact:

Restorative Justice Otago

c/- Anglican Family Care

PO Box 5219

Dunedin, Otago, NZ

email

p: +64 3 477 0801

Interfaith Engagement for Peace: a Muslim Perspective

I’m delighted to learn (and publicise) that Ingrid Mattson (who holds the Chair in Islamic Studies at Huron University College at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada) will deliver this year’s Open Peace Lecture at the University of Otago.

I’m delighted to learn (and publicise) that Ingrid Mattson (who holds the Chair in Islamic Studies at Huron University College at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada) will deliver this year’s Open Peace Lecture at the University of Otago.

The title of Dr Mattson’s lecture is ‘Interfaith Engagement for Peace: a Muslim Perspective’.

When: Monday 19 August, 1730–1900, followed by supper.

Where: Burns 1 Lecture Theatre, Dunedin.

All are welcome. The event is being sponsored by the Dunedin Abrahamic Interfaith Group and Otago Tertiary Chaplaincy.

A review of ‘Barth’s Interpretation of the Virgin Birth’

Barth’s Interpretation of the Virgin Birth: A Sign of Mystery, by Dustin Resch. Farnham/Burlington: Ashgate, 2012. ix + 218pp; ISBN 978 1 4094 4117.

Barth’s Interpretation of the Virgin Birth: A Sign of Mystery, by Dustin Resch. Farnham/Burlington: Ashgate, 2012. ix + 218pp; ISBN 978 1 4094 4117.

In Barth’s Interpretation of the Virgin Birth, Dustin Resch (Assistant Professor of Theology and Dean of the Seminary at Briercrest College and Seminary) offers us a clearly written introductory survey to Barth’s presentation of the doctrine of the virgin birth, unencumbered with detail and critical interaction.

With a view to setting Barth’s contribution in its theological context, the study begins, appropriately, with a brief overview of the doctrine in the Western tradition. Here, particular attention is given to treatments by Irenaeus, Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Schleiermacher, Strauss and Brunner, and to the ways that the pre-Reformation articulations of the tradition tended to evaluate the doctrine in terms of its ‘fittingness’ with the broader themes of christology, pneumatology and original sin. This emphasis, Resch argues, ‘slipped into the background during the Reformation, which aimed to chasten what the Reformers took to be undue speculation, particularly about Mary’ (p. 36), only to emerge again during the modern period, albeit in ways that argued for its fundamental un-fitness in the courtroom of critical biblical scholarship and modern biology, and therefore without any significant theological value. Resch proceeds to argue that Barth takes up the Augustinian heritage of the virgin birth, but revises it such that Barth believes he escapes the criticisms of its modern despisers. The success or otherwise of Barth’s efforts here are left largely untested by Resch.

In the second chapter, Resch offers an exposition of the methodological and exegetical features of Barth’s development of the doctrine from his early work at Göttingen and Münster up to the introductory volume of Die Kirkliche Dogmatik. Locating Barth’s unembarrassed claims on the virgin conception vis-à-vis the Augustinian, Schleiermacherian, Harnackian and modern Roman Catholic traditions, and as a dogmatic bookend to Jesus’ miraculous resurrection, Resch convincingly rehearses throughout the ways in which, for Barth (post-Münster), the virgin birth functions as a fitting theological ‘sign’ (Zeichen) of the mystery of the incarnation – rather than making any claims about the constitutive significance of Jesus’ person as the Logos incarnate or about biology and the wonders of parthenogenesis – which directs the church to a number of its basic dogmatic claims. As P.T. Forsyth – the so-called ‘Barthian before Barth’ (a great compliment to Barth!) – had earlier shown, the virgin birth is really a theological rather than a critical question. It is not a necessity created by the integrity and authority of Scripture per se but a necessity created (if at all) by the solidarity of the gospel, and by the requirements of grace. In terms of epistemology, for example, it recalls that ‘the beginning of our knowledge of God … is not a beginning which we can make with God. It can be only the beginning which God has made with us’ (CD II/1, 190). For Barth, the Bible’s presentation of the miracle of the virgin birth has ‘no ontic but [only] noetic significance’ (Credo, p. 69), its concern being the mystery of God’s free grace. Hence the Bible evidences a complete lack of concern with scientific explanation and is wholly concerned with the question of the sheer mystery and grace of revelation, a mystery and grace which announce, among other things, the foundationless nature of all our presuppositions about, and our semi-Pelagian gropings for, God. It is, literally, to begin again at the beginning; i.e., with God’s self-giving in Jesus Christ. Ontology, in other words, for Barth, must always precede epistemology.

Notwithstanding the comments made above vis-à-vis Scripture, Resch suitably notes, however, that Barth’s treatment of the virgin birth as a sign relating to the mystery of the incarnation rather than as a constitutive element of Christ’s person was one that was ‘derived exegetically and was not a theological decision made simply to avoid the criticism of modern theology’ (p. 62). So Resch:

For Barth, the criteria by which the church should make its decision to adopt the biblical attestation of the virgin birth into its understanding of the biblical message should be the same as the criteria by which the New Testament authors themselves decided to incorporate the virgin birth into their witness. In both cases, questions of the age and source value of the tradition were not conclusive. Instead, the doctrine was accepted because of its ‘fit’ with the central elements of Christian faith. (pp. 73–74)

This theological reading of the Gospel texts, as Resch notes in a number of places, enabled Barth to avoid many of the charges often laid at Augustinian interpretations of the doctrine, and that while guarding the mystery of Christ’s person from being collapsed into a general truth or principal. That said, Resch is also concerned to map how, for Barth, the virgin birth functions as a ‘paradigm’ through which to understand not only the shape of God’s work upon human beings but also something about the corresponding posture of faith’s being-before-God, features borne out well by Resch not only in terms of Barth’s treatment of Mary but also, and perhaps especially, through his attendance to the largely ignored figure of Joseph who ‘clearly has no capacity for God, but rather is elected to serve Christ in the world as his guardian. Understood this way’, Resch notes in a later chapter, ‘Joseph becomes an excellent metaphor for Barth’s view of the church’ (p. 175). In Barth’s own words:

This theological reading of the Gospel texts, as Resch notes in a number of places, enabled Barth to avoid many of the charges often laid at Augustinian interpretations of the doctrine, and that while guarding the mystery of Christ’s person from being collapsed into a general truth or principal. That said, Resch is also concerned to map how, for Barth, the virgin birth functions as a ‘paradigm’ through which to understand not only the shape of God’s work upon human beings but also something about the corresponding posture of faith’s being-before-God, features borne out well by Resch not only in terms of Barth’s treatment of Mary but also, and perhaps especially, through his attendance to the largely ignored figure of Joseph who ‘clearly has no capacity for God, but rather is elected to serve Christ in the world as his guardian. Understood this way’, Resch notes in a later chapter, ‘Joseph becomes an excellent metaphor for Barth’s view of the church’ (p. 175). In Barth’s own words:

Though I am very averse to the development of ‘Mariology’, I am very inclined to ‘Josephology’, because in my eyes Joseph has played a role with respect to Christ which the church should adopt. I know that the Roman Church prefers to compare its role with the glorious role of Mary. It brings the Christian message to the world in the same way in which Mary has given us Christ. But the comparison deceives. The church cannot give birth to the Redeemer; but it can and must serve him with humble and discrete enthusiasm. And that was exactly the role that Joseph played, who always held himself in the background and left all fame to Jesus. Exactly that should be the role of the church, if we want the world to rediscover the glory of the Word of God. (‘Über die Annäherung der Kirchen: Ein Gesprach zwischen Karl Barth und Tanneguy de Quénétain’, Junge Kirche: protestantische Monatshefte 24 (1963): 309)

Chapter Three is concerned to examine Barth’s doctrine of the virgin birth in relation to his presentation of Christ’s sinless humanity and original sin in the Church Dogmatics. In particular, Resch maps the ways that, for Barth, Christ’s birth through the virgin Mary attests to both the ‘Yes’ of God’s grace to humanity and, because of the absence of a human father, to God’s ‘No’ of judgment against sinful human beings: ‘The natus ex Maria virgine unambiguously negates the possibility of viewing revelation and reconciliation as a possibility latent within human beings by describing the mystery of the sovereign act of God in the incarnation. It does this “by an express and extremely concrete negative”. This negative – symbolized by the removal of the man – indicates the limitation of human participation in the incarnation’ (p. 85).

In Chapter Four, Resch brings Jesus’ conception into conversation with Barth’s pneumatology, noting how the former, which remains sui generis, functions, for Barth, as a pattern for, and a heuristic tool – ‘a distinctive mark’ – to interpret, the work of the Spirit in the lives of those who ‘perceive and accept and receive [Jesus Christ] as the Reconciler of the world and therefore as their Reconciler’ (CD IV/1, 148). It is argued that, just as Mary was enabled by the Spirit to conceive Christ within her womb, so too are Christians enabled by the same Spirit to receive the revelation and reconciliation of God.

Mary’s role in Barth’s theology is given fuller attention in the final chapter where Resch helpfully outlines how Barth’s treatment of Mary’s ‘readiness’ (Bereitschaft) before God informs both his understanding of the relationship between divine grace and human agency, and his evaluation of Roman Catholic Mariology, noting the ways that Barth’s acceptance of the virgin birth happens by the same criteria by which he rejects Mariology; namely, with its fit with the mystery of the incarnation. ‘Barth’s main problem with Mariology’, Resch avers, ‘is simply that in it Mary is treated in relative independence from Christ. While never completely severed from Christ, Mary has come to have her own special dignity, merit and ministry. In contrast with the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, and particularly the New Testament, according to Barth, Roman Catholic Mariology fails to use the term Theotokos as an exclusively Christological title … The Catholic Mary is, for Barth, the symbolic portrayal of the philosophical concept of the analogia entis’ (pp. 168–69, 177). Conversely, Barth will insist that human readiness for God – and God’s readiness for humanity – is found in, and is synonymous with, Christ alone.

Throughout the essay, Resch successfully illustrates ways that Barth’s thinking on the virgin birth remains both broadly Augustinian insofar as the doctrine relates to that of original sin, and radically revisionist insofar as Barth departs from Augustine’s interpretation of the virgin birth as that which mysteriously preserves Christ from the tainting effects of concupiscence and original sin and conceives it instead as a symbol of the dialectic that the incarnation itself announces – the futility of all human willing, acting and striving for the grace of God, and the divine determination and gracious freedom to call into existence things that do not exist (Rom 4.17).

Readers (and I suspect Resch himself too) may well be left asking, however, whether Resch has bought too uncritically into Barth’s Protestant critique of Mariology, and whether his heavy reliance on a somewhat limited scope of Barth’s work (mainly The Great Promise and CD I/2) leaves his presentation less satisfying than it might be. More frustrating, however, is the exhausting repetition throughout the book. Where the reader may be hoping to find a new vista around the next corner, or an idea further developed in conversation with other themes pertaining to the subject (e.g., the doctrines of election and creation, the relationship between ‘sign’ and ‘ontology’ and between this particular ‘sign’ and other ‘signs’, the relationship between the objective basis and subjective experience of faith’s participation in the faithfulness of Christ as the vicarious human given by God, discipleship and prayer, how Mary’s and Joseph’s fittingness relates to that of other characters throughout the Bible, etc. are all left too uncooked) or with at least some significant secondary literature, the reader discovers instead that he is simply back where he has been numerous times before, and little the wiser for the effort. I suspect, nonetheless, that we are not here dealing with a case of an author who does not know where the real questions lie – indeed, he identifies some very worthwhile trajectories for further thought in his conclusion; Barth’s rather one-dimensional presentation of Mary divorced from her existential situation, for example – but perhaps with a matter of confidence and/or energy to traverse there within the bounds of this project. One hopes that in future work, he builds on the reliable foundation laid here.

[In due course, a version of this review will appear in The Journal of Theological Studies]

Two conferences to note

The department of theology at Durham University is hosting a one-day colloquium (13 June) on Ecumenical Readings of Aquinas. It will include presentations by Andrew Davison, Christopher Insole, Marcus Plested and Lewis Ayres. Details here.

The department of theology at Durham University is hosting a one-day colloquium (13 June) on Ecumenical Readings of Aquinas. It will include presentations by Andrew Davison, Christopher Insole, Marcus Plested and Lewis Ayres. Details here.

The Australian Catholic University is organising a conference titled ‘Addressing the Sacred through Literature and the Arts’ (2-3 August). The conference will aim to ‘address acts of creation and co-creation and encourage a dialogue between artists, scholars and audiences in a mutual exploration of the sacred’. Keynote speakers are Amanda Lohrey, Kevin Hart and Rosemary Crumlin. Details here.

For details about other theology conferences, visit here.

On the anniversary of our baptisms

Religious rituals are important because by them truths (and not only truths) are inscribed in us, because by them we have opportunity to rehearse those things that matter deeply to us and to do so with others, and because it is among such rituals that the loose and sometimes deeply painful and paradoxical strands of our life are held, and that in ways that take our location seriously and which are, one hopes, intentionally faithful to a broader and deeper narrative into which our lives have been taken up, the old old story by which we live and move and are measured. So understood, it’s little wonder that C.S. Lewis, in A Preface to Paradise Lost, spoke of ‘the proper pleasure of ritual’. Of course, not all rituals could properly be defined as ‘acts of pleasure’. Nor are all handmaidens of an overtly religious imagination. Monday afternoon netball, or pre-bed activities of endless calls for ‘toilet, teeth, and pajamas’, or story time, or a wee dram of aqua vitae, for example, readily come to mind. And while these latter types of activity seem to be no less important for our formation, and while they are common enough, they are not what we might call ‘catholic’ in nature.

I mention this because one of the most important things one can do as a public citizen is to remind catholic bodies that the local situation is where the real action is. It is equally important that the correspondent reality is manifest; namely, to remind the local clan that its raisons d’être are most faithfully conceived in light of a – or the – catholic story. And we need rituals that perform both tasks, that celebrate both realities.

To return to the matter of more overtly ‘religious’ rituals, my most local tribe – which consists of my partner and I and our three begats (1, 2 and 7) – practices a number of such and that with, it must be said, modulating degrees of regularity and intentionality. However, one of the ‘rituals’ that we celebrate with particular enthusiasm and without fail is the various anniversaries of our baptisms (this week it was mine). So, five times a year, usually after dinner – or between main course and dessert, depending on where clan members are on the sanity-ometer at that particular moment – we clear the table, light a candle, put out a small bowl of water and recite the following liturgy together (drawn, with some modification, from the excellent Uniting in Worship 2, a liturgical resource produced by the Uniting Church in Australia. I intend, at some stage, to write an entirely new liturgy but at the moment this is what we use), rotating the leader from occasion to occasion. The words in bold are said by all.

1. INTRODUCTION

Brothers and sisters,

in our baptism, we died and were buried with Christ,

so that we might rise with him to new life.

We were initiated into Christ’s holy Church

and brought to life through water and the Spirit.

God’s mighty acts of salvation for us and all people

are gracious gifts, freely given.

Today we come to reaffirm our baptism,

declaring our allegiance to the risen Christ

and seeking to be obedient to his will.

2. REAFFIRMATION OF BAPTISM

Do you repent of your sins?

I repent of my sins.

Do you turn to Jesus Christ

who has defeated the power of sin and death

and brought us new life?

I turn to Christ.

Do you commit yourself to God,

trusting in Jesus Christ as Saviour

and in the Holy Spirit as God’s power and presence along the way?

I commit myself to God.

THE APOSTLES’ CREED

And now I ask you to confess the faith

into which you were baptised,

and in which you continue to live and grow.

Do you believe in God?

I believe in God, the Father almighty,

creator of heaven and earth.

Do you believe in Jesus Christ?

I believe in Jesus Christ, God’s only Son, our Lord,

who was conceived by the Holy Spirit,

born of the Virgin Mary,

suffered under Pontius Pilate,

was crucified, died, and was buried;

he descended to the dead.

On the third day he rose again;

he ascended into heaven,

he is seated at the right hand of the Father,

and he will come to judge the living and the dead.

Do you believe in the Holy Spirit?

I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

the forgiveness of sins,

the resurrection of the body,

and the life everlasting. Amen.

This is the faith of God’s baptised people.

We are not ashamed to confess it

in Christ our Lord.

COMMITMENT TO MISSION

I ask you now to pledge yourselves

to Christ’s ministry in the world.

Will you continue in the community of faith,

the apostles’ teaching,

the breaking of bread and the prayers?

With God’s help, we will.

Will you proclaim by word and example

the good news of God in Christ?

With God’s help, we will.

Will you seek Christ in all people,

and love your neighbour as yourself?

With God’s help, we will.

Will you strive for justice and peace,

and respect the dignity of every human being?

With God’s help, we will.

May almighty God,

who has given us new birth by water and the Holy Spirit,

keep us steadfast in the faith,

and bring us to eternal life;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

3. RECOLLECTION OF BAPTISM

The leader pours water into the bowl, saying:

Come, Lord Jesus,

refresh the lives of all your faithful people.

The leader places her/his hand into the bowl and then sprinkles the rest of the family three times saying:

Sisters and brothers:

Always remember you are baptised,

and praise the Holy Spirit.

THE SIGN OF THE CROSS

Today we remember that, from the time of our baptism,

the sign of the cross has been upon us.

I invite you now to join me

in tracing the sign of the cross upon your forehead,

saying: I belong to Christ. Amen.

Everyone places their fingers into the bowl and then marks themselves with the sign of the cross, saying:

I belong to Christ. Amen.

You are now invited to trace the sign of the cross

on those around you,

saying: You belong to Christ. Amen.

Everyone places their fingers into the bowl and then marks each other person at the table with the sign of the cross, saying:

You belong to Christ. Amen.

4. PRAYERS

Let us pray for all the baptised everywhere

and for ourselves in this congregation of God’s people.

That our redemption from evil

and our rescue from the way of sin and death

may be evident in our daily living.

Lord, in your mercy,

hear our prayer.

That the Holy Spirit may continue

to open our hearts and lives

to the grace and truth we find in Jesus our Lord.

Lord, in your mercy,

hear our prayer.

That we may be kept in the faith and communion

of the holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

Lord, in your mercy,

hear our prayer.

That we may be sent into the world

to witness to the love of Christ.

Lord, in your mercy,

hear our prayer.

That we may be brought to the fulness

of God’s peace and glory.

Lord, in your mercy,

hear our prayer.

Other prayers are offered here for other people/situations that lay heavy on our hearts.

Then to conclude the prayers, we say together:

Praise be to you, our Lord Jesus Christ,

for all the benefits

you have won for us,

for all the pains and insults

you have borne for us.

O most merciful Redeemer,

friend and brother,

may we know you more clearly,

love you more dearly,

and follow you more nearly,

day by day. Amen.

5. THE PEACE

We are the body of Christ.

In the one Spirit we were all baptised into one body.

Let us then pursue all that makes for peace

and builds up our common life.

May stations …

- Hammarskjold: A Life by Roger Lipsey (Posts on this book here, here and here)

- The Place of Bonhoeffer: Problems and Possibilities in His Thought, edited by Martin E. Marty

- Wheat Belly by William Davis

- The Island of the Women and Other Stories by George Mackay Brown

- Northern Lights: A Poet’s Sources by George MacKay Brown

- Three Plays by George Mackay Brown

Listening:

- The Low Highway by Steve Earle

- A German Requiem by Brahms

Watching:

St. Patrick’s Bad Analogies

A little post-Trinity Sunday levity:

‘Ministry As Difficult As It Ought to Be’, by Will Willimon

Will Willimon’s latest piece, a version of an article previously-published in The Christian Century, is well worth the read. It’s entitled ‘Ministry As Difficult As It Ought to Be’, and I thought it worth reproducing here. Willimon’s words speak powerfully to pastors, to theological educators, to church committees set up to discern/assess calls about future pastors, and more:

Will Willimon’s latest piece, a version of an article previously-published in The Christian Century, is well worth the read. It’s entitled ‘Ministry As Difficult As It Ought to Be’, and I thought it worth reproducing here. Willimon’s words speak powerfully to pastors, to theological educators, to church committees set up to discern/assess calls about future pastors, and more:

“See our big buildings?” asked the Medical School Dean as he swept his hand across the panorama of the Duke Medical Center. “Their purpose is production of a handful of doctors who can be trusted to be alone with a naked patient. Takes us four years.”

I repositioned the Dean so that he faced the less impressive neogothic Divinity School. “That’s where we teach our seminarians to be in awkward situations with naked, vulnerable parishioners. It only takes us three years.”

After two quadrennia as a church bureaucrat, slogging in the muck and mire of ecclesiastical trenches — sending pastors to remote, unappealing locations where Jesus insists on working — I’m again teaching in that amazing countercultural phenomenon called a seminary.

I was honored to serve with eight hundred fellow clergy who risked United Methodism in Alabama, though I leave behind a subpoena and three law suits; don’t tell Governor Bentley that I’ve now fled the state.

Being bishop gave me a front row seat to observe ministry in the Protestant mainline that is being rapidly sidelined. Pastoral leadership of a mainline congregation is no picnic. My admiration is unbounded for clergy who persist in proclaiming the gospel in the face of the resistance that the world throws at them. Now, as a seminary professor, I’m eager to do my bit in the classroom to prepare new clergy for the most demanding of vocations.

Consumer Corrupted Clergy

From what I saw, too many contemporary clergy limit themselves to ministries of congregational care-giving – soothing the fears of the anxiously affluent. One of my pastors led a self-study of her congregation. Eighty percent responded that their chief expectation of their pastor was, “Care for me and my family.”

I left seminary in the heady Sixties, eager to be on the front line in the struggle for a renaissance of the church as countercultural work of God. By a happy confluence of events, the church was again being given the opportunity to be salt and light to the world rather than sweet syrup to enable the world’s solutions to go down easier.

Four decades later as bishop I saw too many of my fellow clergy allow congregational-caregiving and maintenance to trump other more important acts of ministry like truth-telling and mission leadership. Lacking the theological resources to resist the relentless cloying of self-centered congregations, these tired pastors breathlessly dashed about offering their parishioners undisciplined compassion rather than sharp biblical truth.

North American parishes are in a bad neighborhood for care-giving. Most of our people (at least those we are willing to include in mainline churches) solve biblically legitimate need (food, clothing, housing) with their check books. Now, in the little free time they have for religion, they seek a purpose-driven life, deeper spirituality, reason to get out of bed in the morning, or inner well-being – matters of unconcern to Jesus. In this narcissistic environment, the gospel is presented as a technique, a vaguely spiritual response to free-floating, ill-defined omnivorous human desire.

A consumptive society perverts the church’s ministry into another commodity which the clergy dole out to self-centered consumers who enlist us in their attempt to cure their emptiness. Exclusively therapeutic ministry is the result. I saw fatigue and depression among many clergy whom I served as bishop. Debilitation is predictable for a cleros with no higher purpose for ministry than servitude to the voracious personal needs of the laos.

The 12 million dollar Duke Clergy Health study implies that our biggest challenge is to drop a few pounds and take a day off. If you can’t be faithful, be healthy and happy. I believe that our toughest task is to love the Truth who is Jesus Christ more than we love our people who are so skillful in conning us into their idolatries.

Seminaries, Wake Up

Yet I must say that by comparison, the poor old demoralized mainline church, for all its faults, is a good deal more self-critical and boldly innovative than the seminary. Our most effective clergy are finding creative ways to critique the practice of ministry, to start new communities of faith, to reach out to underserved and unwelcomed constituencies, and to engage the laity in something more important than themselves. Alas, seminaries have changed less in the past one hundred years than the worship, preaching, and life of vibrant congregations have changed in the last two decades.

As bishop I served as chair of our denomination’s Theological Schools Commission. Most of our seminaries are clueless, or at least unresponsive, to the huge transformation that is sweeping through mainline Protestantism. We have so many seminaries for one reason: the church has given seminaries a monopoly on training our clergy with no accountability for the clergy they produce. Increasing numbers of our most vital congregations say that seminary fails to give them the leadership they now require. Oblivious to our current crisis, seminaries continue to produce pastors for congregational care-giving and institutional preservation. The result is another generation of pastors who know only how to be chaplains for the status quo and managers of decline rather than leaders of a movement in transformational faith. As a fellow bishop said, “Seminaries are still cranking out pastors to serve healthy congregations, giving us new pastors who are ill equipped to serve two-thirds of my churches.”

In just a decade, United Methodists, various Presbyterians, Lutherans, and Episcopalians will have half of our strength and resources – judgment upon our unfaithful limitation of ministry to a demographic (mine) that is rapidly exiting. After decades of study, finger-pointing and blaming, we now know that a major factor in our rapid decline is our unwillingness to go where the people are and to plant new churches. Yet few traditionalist mainline seminaries teach future pastors how to start new communities of faith.

My new pastors repeatedly told me: “We got out of seminary with lots of good ideas but without the ability to lead people from here to there.” “I’ve learned enough to know that something is bad wrong with the current church but I don’t know where to begin to fix it.” Seminaries produce clergy rich in ideas but impoverished in agency, well-intentioned in care giving but deficient in leadership.

After interviewing a dozen seminarians at one of our prestigious seminaries, I asked my District Superintendents, “How many interviewees could be helpful in the work that we believe God has assigned us in Alabama?”

They identified two of the twelve. “Seminaries are run by professors whose life goal is acquisition of academic tenure,” said one DS. “Why ask the seminary to give us innovators who take risks and hold people accountable for their discipleship?”

We found that too many of our pastors want to be John on Patmos, dreaming dreams and seeing visions, when what we badly need is Paul in Corinth, doing the tough, persistent, measureable work required to initiate new communities of faith. If that much touted moniker “servant leader” means anything, it means someone who is willing to submit to what the institution now needs doing for the common good in this time and place. Mainline churches who want to be part of God’s future need leadership by impatient instigators rather than patient caretakers for the ecclesial status quo.

Our Board of Ordained ministry habitually asked candidates unrevealing questions like, “What are your gifts and graces for ministry?”

Surprise, the would-be pastors were incredibly gifted.

I got the Board to ask behavioral questions like, “When is the last time you started a ministry?” “Tell us about your most recent failure in the church. What did you learn?” No ventures, no leadership; no failures, no initiatives.

Don’t dismiss my criticism of seminaries as due to anxiety about a dying institution. Though anxiety is an appropriate response to death, my impetus for concern is Christological. Scripture renders a living agent on the move. “God never rests!” thunders Barth. The Lord of the church means to reign over a far more expansive realm than the church. Nothing in the message or work of Christ justifies a settled, parochial, sedate, care-giving style of ministry that comforts one generation (the average Methodist is 59), cares for aging real estate, and ceases all efforts to get the news to a violent, despairing world that, in Jesus Christ, God is decisively doing something about what’s wrong with the world.

So in this semester’s The Local Church in Mission class rather than have students write a paper on their theology of mission, I’m having them attempt to start up some mission in a church context. Then they are to tell me what they have learned about the leadership skills they need to obtain if they are to be a pastor in a North American church that finds itself in a missionary situation.

One of my pastors succeeded in planting a congregation in a marginalized, primarily Spanish-speaking community (where we have closed three churches in the past ten years). I spent a day with her, primarily to urge her to go back to school and finish her seminary education. During the course of the day she told me that in her previous life she had started three restaurants. Two failed, one finally succeeded. I not only understood why God had used her so effectively in this church start but also why I ought to put her in charge of our new church development rather than send her to seminary.

Seminaries have got to find ways to listen to the church’s cry for bold, transformative clergy leaders to serve the church in the present hour or seminaries face a bleak prospectus.

Theological Refurbishment

Seminaries must remember that the most interesting thing about clergy is not that we have acquired savvy management skills or have been given esoteric knowledge that is unavailable to the lowly baptized. The One who calls and makes clergy, the One who is in ministry and mission rocking the world (whether we are or not) is ultimately the only good reason to be a pastor. Leadership in the name of Jesus is inherently energetic, transformative leadership that challenges and enables Christians to participate in the ever-expanding Realm of God. Pastors have the privilege of expending our lives for someone more important than ourselves or our congregations. We get to serve a people on the move because they are in the grip of a God who refuses to be God alone and leave us to our own devices.

After my prattling about how the sixth century prophets inform our work as pastors, a surly seminarian piped up, “So Jesus explains how you got to be pastor of a large church and a bishop?” Being a seminary professor is more difficult than it looks.

As I look out upon the students in my Intro to Christian Ministry class, I hear Jesus say, “Hey, I’m doing my part to give your church a future. I’m giving you all the resources you need to be faithful.”

Then I hear Jesus sneer, “Would you people at Duke try not to bore to death those whom I’ve summoned to give your church a future?”

I agonized with a pastor about what he could do to stop his congregation from self-destruction. Had he tried a consultant? Yes. Had he secured a crisis counselor? Yes.

“I keep thinking that maybe our disintegration is not something I did or didn’t do,” the pastor said, “or even due to our bad history. I wonder if our demise is caused by Jesus.”

What?

“Maybe Jesus has used our way of being church as much as he intends. Perhaps the Holy Spirit is moving somewhere else? Only Jesus can birth a church; maybe he’s the only one who’s got a right to kill it.”

How willing are we clergy to risk service to such a demanding Savior?

Seminary’s grand goal? Theological education makes ministry in the name of Jesus Christ as difficult as it ought to be. In sending each new wave of pastors, seminaries have the opportunity to theologically regenerate the church, giving the church and its pastoral leaders some canon of measurement greater than institutional health or cultural relevance. Seminarians come to us more adept at construal of their world through a-theistic categories, most of them purloined from the reigning social sciences, than theological canons. Our job is to train the church’s leaders in a rigorously theological refurbishment of the church.

Training people to minister in the name of Jesus is a huge challenge — because of Jesus. His vision of a new, reborn humanity, the extravagant reach of his realm, the constant outward, Trinitarian momentum, the command not only to belief the faith but also to enact and embody the faith, Christ’s revelation of the God whom we did not expect, Christ’s determination to save sinners, only sinners, all make leadership in Jesus’ name a daunting task.

I received a heated email from a long-time member of one of my churches complaining that during the Sunday service the pastor had prayed for the salvation of Osama bin Laden. “We don’t pay a preacher to pull a stunt like that,” whined the lay leader.

I called the pastor, explaining to him that his behavior was difficult for the laity to handle, asking him if he had used good judgment to pray such a thing during our national crisis.

With distinct annoyance the pastor replied, “Just for your information bishop, I happen to believe that the Jew who said, ‘Pray for your enemies and bless those who persecute you,’ is the Son of God.”

In my courses I face a two-fold challenge: responsibility to hand over what we’ve learned in two thousand years of leading in the name of Jesus, indoctrinating a new generation of pastors into the God-given wisdom of the church and taunting would-be pastoral leaders to step up and help the church think, pray, and act our way out of our present malaise.

“Here kid, watch me now,” I say in my classes, “here’s the way my generation tried to serve the church and its mission. Now, here’s my list of failures and disappointments. God has sent you to overcome my generation’s limitations in doing church. Go for it!”

In spite of my best intentions, my classes in ministry sometimes degenerate into techniques for success, managerial tips and tricks, and irresistible, knock down arguments for effective ministry; atheism that ministers as if God doesn’t matter.

Still, my students keep calling me back to the theological wonders that convene us, another benefit of working almost exclusively among those who outrageously believe that they have been summoned, commandeered, called by God to leadership in the Body of Christ. Whatever God wants to do with the world, God has decided to do it with them.

The paradigmatic story of their enlistment is Exodus 3, the call of Moses. (We made our entering students read Gregory’s Life of Moses to prepare them for Duke Divinity.) When summoned to leadership, Moses asks, “Who are you that you should send me?”

Moses cannot represent a deity without knowing the peculiar identity of the God who sends him against the empire. Nor can we. The best work we do in the seminary classroom is investigation and reiteration of the identity of the Triune God who, in every time and place, summons the people required to help the church to be faithful, giving them the grace needed to keep ministry as difficult as God needs it to be.

I begin my class by asking students to describe, in less than five pages, how they got to seminary, “My Call to Christian Leadership.” Reading those papers is a faith-engendering experience. People jerked out of secure positions in perfectly good professions, bright young things commandeered and shoved into a very different life trajectory, a nurse to whom Jesus personally appeared on a patio. All I could say, when I finished reading those papers was, “Wow. Jesus is more interesting (and dangerous) than even I knew.”

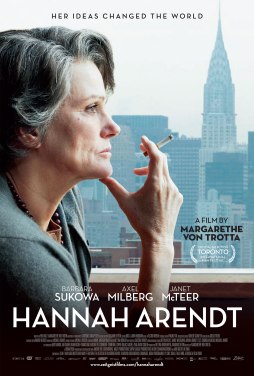

Waiting for ‘Hannah Arendt’

It’s been a while since I really looked forward to a film’s release, but I’m on the edge of my seat awaiting Margarethe von Trotta’s award-winning Hannah Arendt. The film’s focus is Arendt’s controversial reporting for the The New Yorker on the 1961 Adolf Eichmann trial, what Arendt named the ‘show trial’. Of course, one of the reasons for why this and other similar trials were so named by Arendt was because of her deep-seated conviction, expressed in a letter to her Doktorvater Karl Jaspers and published in Correspondence 1926-1969, that ‘the Nazi crimes … explode the limits of the law’. Indeed, ‘that is precisely what constitutes their monstrousness. For these crimes’, she continues, ‘no punishment is severe enough. It may well be essential to hang Göring, but it is totally inadequate. That is, this guilt, in contrast to all criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems. That is the reason why the Nazis in Nuremberg are so smug … We are simply not equipped to deal, on a human, political level, with a guilt that is beyond crime’. As she would write in Eichmann in Jerusalem: ‘The purpose of a trial is to render justice, and nothing else; even the noblest of ulterior purposes — “the making of a record of the Hitler regime which would withstand the test of history” … — can only detract from the law’s main business: to weigh the charges brought against the accused, to render judgment, and to mete out due punishment’.

It’s been a while since I really looked forward to a film’s release, but I’m on the edge of my seat awaiting Margarethe von Trotta’s award-winning Hannah Arendt. The film’s focus is Arendt’s controversial reporting for the The New Yorker on the 1961 Adolf Eichmann trial, what Arendt named the ‘show trial’. Of course, one of the reasons for why this and other similar trials were so named by Arendt was because of her deep-seated conviction, expressed in a letter to her Doktorvater Karl Jaspers and published in Correspondence 1926-1969, that ‘the Nazi crimes … explode the limits of the law’. Indeed, ‘that is precisely what constitutes their monstrousness. For these crimes’, she continues, ‘no punishment is severe enough. It may well be essential to hang Göring, but it is totally inadequate. That is, this guilt, in contrast to all criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems. That is the reason why the Nazis in Nuremberg are so smug … We are simply not equipped to deal, on a human, political level, with a guilt that is beyond crime’. As she would write in Eichmann in Jerusalem: ‘The purpose of a trial is to render justice, and nothing else; even the noblest of ulterior purposes — “the making of a record of the Hitler regime which would withstand the test of history” … — can only detract from the law’s main business: to weigh the charges brought against the accused, to render judgment, and to mete out due punishment’.

I’m really interested to see how von Trotta deals with these difficult themes in the film. By the way, for those interested in reading an outstanding and critical (here meant in both senses of the word) engagement with these ideas may I commend to you Lawrence Douglas’ The Memory of Judgment: Making Law and History in the Trials of the Holocaust, a book that I shall probably re-read in preparation for seeing the film.

The film’s synopsis reads:

HANNAH ARENDT is a portrait of the genius that shook the world with her discovery of “the banality of evil.” After she attends the Nazi Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem, Arendt dares to write about the Holocaust in terms no one had ever heard before. Her work instantly provokes a scandal, and Arendt stands strong as she is attacked by friends and foes alike. But as the German-Jewish émigré struggles to suppress her own painful asso- ciations with the past, the film exposes her beguiling blend of arrogance and vulnerability – revealing a soul defined and derailed by exile.

The film portrays Hannah Arendt (Barbara Sukowa) during the four years, (1961 to 1964), that she observes, writes, and endures the reception of her work on the trial of the Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann. Watching Arendt as she attends the trial, staying by her side as she is both barraged by her critics and supported by a tight band of loyal friends, we experience the intensity of this powerful Jewish woman who fled Nazi Germany in 1933. The fierce, chainsmoking Arendt is happy and flourishing in America, but her penetrating vision makes her an outsider wherever she goes.

When Arendt hears that the Israeli Secret Service has kidnapped Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires and brought him to Jerusalem, she is determined to report on the trial. William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson), the editor of “The New Yorker” magazine, is thrilled to have such an esteemed intellectual cover the historic process, but Arendt’s husband, Heinrich Blücher (Axel Milberg), is not so sure. He worries that this encounter will put his beloved Hannah back into what they both call the “dark times.”

Arendt enters the tense Jerusalem courtroom expecting to see a monster and instead she finds a nobody. The shallow mediocrity of the man cannot be easily reconciled with the profound evil of his actions, but Arendt quickly realizes that this contrast is the puzzle that must be solved. Arendt returns to New York and as she begins to discuss her groundbreaking interpretation of Adolf Eichmann, fear ripples through her best friend, Hans Jonas (Ulrich Noethen). Her philosophical approach will only cause confusion, he warns. But Arendt defends her courageous and original perspective and Heinrich supports her all the way. After two years of intense thought,

additional reading, and further debate with her best American friend, Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer) her German researcher and friend, Lotte Köhler (Julia Jentsch) and of course, constant consultation with Heinrich, she finally delivers her manuscript. The publication of the article in “The New Yorker” provokes an immediate scandal in the U.S., Israel, and soon in the rest of the world.

HANNAH ARENDT provides an insight into to the profound importance of her ideas. But even more moving is the chance to understand the warm heart and icy brilliance of this complex and deeply compelling woman.

So far, I’ve been unable to find out any details about when the film opens here in New Zealand (only that it seems that Curious is bringing it out here) and have had to try and satisfy myself with watching the promos and reading a few reviews, including this one published in Der Spiegel. If anyone has any details about when and where I can see it south of the Waitaki, then please let me know.

Susan Sontag on writing in our time

‘The culture-heroes of our liberal bourgeois civilization are anti-liberal and anti-bourgeois; they are writers who are repetitive, obsessive, and impolite, who impress by force—not simply by their tone of personal authority and by their intellectual ardor, but by the sense of acute personal and intellectual extremity. The bigots, the hysterics, the destroyers of the self—these are the writers who bear witness to the fearful polite time in which we live. It is mostly a matter of tone: it is hardly possible to give credence to ideas uttered in the impersonal tones of sanity. There are certain eras which are too complex, too deafened by contradictory historical and intellectual experiences, to hear the voice of sanity. Sanity becomes compromise, evasion, a lie. Ours is an age which consciously pursues health, and yet only believes in the reality of sickness. The truths we respect are those born of affliction. We measure truth in terms of the cost to the writer in suffering—rather than by the standard of an objective truth to which a writer’s words correspond. Each of our truths must have a martyr’. From Susan Sontag’s wonderful review of Simone Weil’s Selected Essays 1934–43.

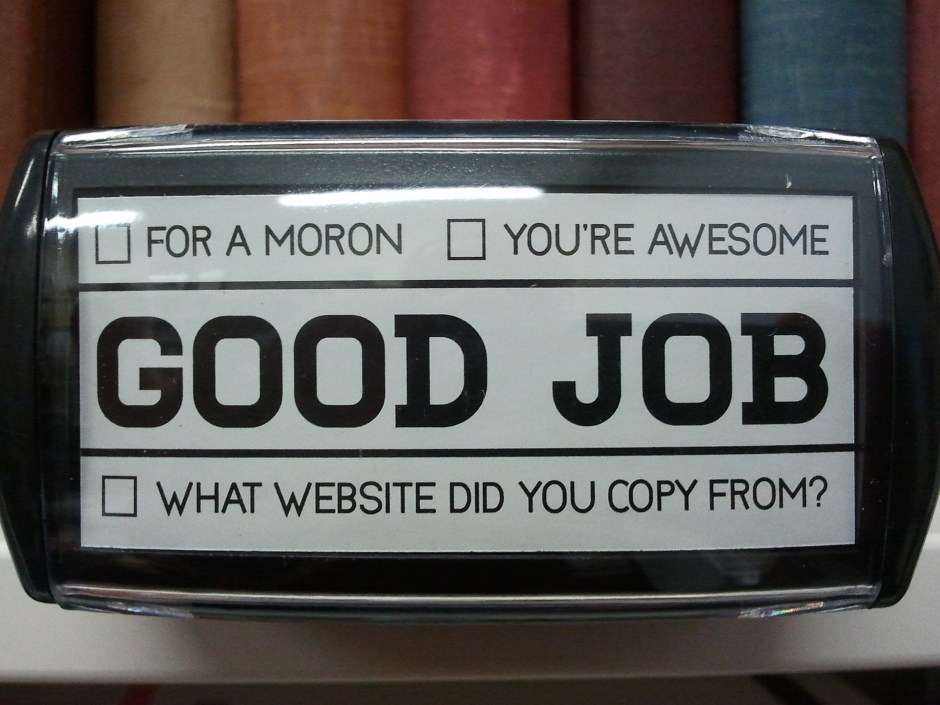

An aid for teaching

‘No matter how often it happens in my courses, I never cease to be infuriated with plagiarism’. So tweeted a friend of mine earlier this week. And every teacher worth his or her salt knows the feeling. His comment coincided nicely with a very practical gift that my thoughtful partner purchased for me just a day or two earlier – a ‘GOOD JOB’ stamp that I’m really looking forward to using the next time I engage in that wonderful form of lovemaking called ‘grading papers’:

Of course, when I think about my current crop of students, I anticipate that mainly only one box will be required. However, the Augustinian in me can certainly imagine occasions when all three boxes will need to be ticked, and sometimes all at once.

On cooking Indian (plus a recipe for Paneer Tikka Masala)

There is something highly addictive about Indian food. In fact, ‘scientists’ (which is the BBC’s name for the odd creatures who typically spend four-fifths of their life trying to secure funding in order to research things that half a dozen people in the world care enough about to bother reading the findings on; not that important matters have typically been the concern of the majority) like a crew at Nottingham Trent University a few years back claim that ‘just thinking about eating a curry can make people feel high and eating it arouses the senses and makes your heart beat faster’. But I‘m not concerned here with that kind of addiction.

There is something highly addictive about Indian food. In fact, ‘scientists’ (which is the BBC’s name for the odd creatures who typically spend four-fifths of their life trying to secure funding in order to research things that half a dozen people in the world care enough about to bother reading the findings on; not that important matters have typically been the concern of the majority) like a crew at Nottingham Trent University a few years back claim that ‘just thinking about eating a curry can make people feel high and eating it arouses the senses and makes your heart beat faster’. But I‘m not concerned here with that kind of addiction.

Rather, I’m concerned about the addiction that attends cooking Indian food. There’s something about the range, the texture and the colour of the various spices, about a home (and a human nose) coming alive with exotic aromas from ingredients grown 14,000 kms away, about the wonderfully friendly and cricket-loving people who run those funky little Indian food marts, and, of course, there’s the thrill – as brimming with eschatological hope as anything ever was – that drives one to produce a curry as near perfect as creatures living anywhere north of the Bellingshausen Station are capable of. Like the thrill of anticipation that attends catching a trout on a fly pattern that you had tied yourself, so too is the joy of creating your own curry recipe (as opposed to simply copying one from some tried and true volume by Camellia Panjabi or Pushpesh Pant). There’s something gloriously physical, too, about preparing Indian dishes. You are involved in the process from go to whoa in ways that many other forms of cooking don’t seem to invite nearly as much. Cooking Indian announces to the cook – and to all who have eyes to see and noses to whiff and palates to tingle – that the only creation worth celebrating, the only creation that is, is the creatio continua. Cooking Indian, in other words, is a prophetic act which exposes the joyless lie of deism and celebrates the joyful freedom of the God of spice. To be sure, such an act of (sub-)creation, of participation in the movement of Spirit in creation – like that which attends fly tying – requires some time-consuming research, patience, and sometimes a few doozies along the way, as with many of life’s most valuable gifts. But the rewards are obvious to all who so venture out (and hopefully to those they cook for as well!).

Had I an editor, s/he would have no doubt deleted the previous paragraphs laden as they are with mixed metaphors and superfluous waffle irrelevant to any definition of a point that this post purports to be about, and demanded that I make plain this post’s purpose in ways that demand less ink and much less of the reader’s patience and time and theological lexica. But I don’t have an editor, so they’re staying put. And having now released a few things off my chest, I am delighted to share a wee recipe – one in progress, for are not all recipes symbols of the provisionality and, in some cases, the idolatry of our attempts at meaning making and of our strange groping for the Bread of Heaven? – for Paneer Tikka Masala. I do so with no apologies in advance for the inconsistent use of measurement systems (something that I’m confident that my intelligent readers will be able to cope with), and with a caveat lector around the fact that I reserve the right to edit the recipe as I further tweak it. Cooking as creatio continua.

By the way, I’m always keen to hear from readers who give the recipes posted here at PCaL a go, and/or who have suggestions arising from their own culinary efforts.

Paneer Tikka Masala

Serves 8–10

Ingredients

For the tikka:

- 1kg of Paneer, cut into 1-inch cubes

- 1 green capsicum, cut into 1-inch pieces

- 1 red capsicum, cut into 1-inch pieces

- 2 tbsp peeled, finely grated ginger

- 4 garlic cloves, finely crushed

- 2 tsp ground cumin

- 2 tsp paprika

- 1 tsp kashmiri chilli powder

- 1 tsp garam masala

- 12 tbsp yogurt

- 6 tbsp olive oil

For the masala:

- 8 tbsp ghee or olive oil

- 3–4 medium-sized onions, very finely sliced

- 2 tbsp peeled, finely grated ginger

- 10–12 garlic cloves, crushed

- 1 tsp ground turmeric

- 3 tsp kashmiri chilli powder

- 3 tsp paprika

- 2 tsp coriander, finely ground

- 2 tsp cumin, finely ground

- 8 tbsp plain yogurt

- 4 medium-sized tomatoes, peeled and finely chopped

- 700 ml chicken stock

- 1/2 tsp salt, or to taste

- 1/2 cup tomato puree

- 2 tsp kasoori methi, crushed

- 1 tsp garam masala

- 8 tbsp chopped coriander leaves

- ½ cup cream

Method

1. In a non-reactive bowl, marinate the paneer and capsicum in the ginger, garlic, cumin, paprika, chilli powder, garam masala and yogurt. Mix well, cover, and refrigerate for a couple of hours. Pour yourself a drink.

2. When you’re ready to cook, it’s time to make the masala. Over medium heat, heat the olive oil in a large lidded pan (I use a large cast iron French oven made by Le Creuset. It has not failed me yet, with any dish). When the oil is hot, put in the onions, and stir until they brown (about 8–10 mins) but don’t burn the little fellas. Then add the ginger and garlic and keep stirring for about a minute. Then add the turmeric, chilli powder, paprika, coriander and cumin. Stir for about 10 seconds, and then add 1 tbsp of yogurt. Stir until it is absorbed (think stock and risotto!), and add the remaining yogurt in the same way – a tbsp at a time.

3. Now add the tomatoes, stopping along the way to give thanks to God for these amazingly versatile little friends, and then fry them for 5–6 minutes on low, or until they turn pulpy. Then add the stock, salt, and tomato puree and bring it all to a gentle simmer. Cover, reduce the heat to low, and simmer gently for 20 minutes, or until the sauce is as thick as a stubborn Methodist (OK, not quite that thick. Think, instead, of somewhere between a nice creamy Anglo-Catholic, that all-too-rare breed of high-church Presbyterian and an ol’ time charismaniac. In other words, thick but thin too. Better still, just think cream.). Stir in the kasoori methi, garam masala and chopped coriander leaves, and, checking the flavour, add more salt if needed. Add the cream, stir gently, and simmer uncovered on very low. Refill your glass and put on some Iris DeMent. If you’ve made it this far and it’s not looking like a complete disaster, then you’re a champion.

4. If you’re someone who likes super smooth gravy, then now is the time to set the blender onto the sauce. After blending, keep it simmering away on very low while you attend to step 5.

5. While the masala is simmering away uncovered, it’s time to cook the paneer and capsicum. Thread the marinated paneer cubes and capsicum onto skewers, brush with oil and grill until lightly browned on all sides. Take the paneer and capsicum off the skewers, place in the masala, stir in well, and serve immediately. (As an alternative to the skewer method, fry the paneer and capsicum in butter/oil until all sides are lightly browned. Or, as an additional but I think less successful alternative, brush each piece of paneer and capsicum with butter/oil and bake in a 180° celsius oven until lightly browned.)

6. Garnish with more chopped coriander leaves (if you’re into pretty food) and enjoy with naan or roti or rice (my preferred type of which is Sona Masoori). More importantly, enjoy it with friends and/or enemies.

Hauerwas on Preaching Without Apology

Some (more) great stuff here from Stanley Hauerwas reading the introduction from his forthcoming book Without Apology: Sermons for Christ’s Church, plus more:

The Beauty of Holiness

A guest post by Chris Green

A guest post by Chris Green

Ps. 96.7-9

1 Thess. 4.3

Heb. 12.15

God means to make us holy. As one of our texts put it, “This is the will of God: your sanctification.” But what does this actually mean? What exactly is it that God wants for us? Simply this: to make us like Christ. St Paul says it directly; we are predestined to be conformed to the image of the Son. Sanctification, then, names the process by which the Father, working in, with, and through us by the Spirit, accomplishes this work of making us like the Son, our humanity through and through glorified by sharing together in the Triune life.

Making us like Christ requires a healing of all that sin has corrupted, disfigured, and destroyed in us. And it requires a reordering and reenergizing of our loves and habits of body, mind, and spirit so that we come to live lives worthy of the gospel. Such radical renovation of our lives depends upon our being baptized in and filled with the Spirit—made to partake of the divine nature, as St. Peter has it—so that we come, over time, to take on Christ’s divine-human likeness. Only in this way are we made apt for God, neighbor, and creation. Only in this way are we made truly ourselves.

If we aren’t careful, however, our talk about holiness will slide into nonsense—or something worse. In many people’s minds, the call to holiness is a call to a certain kind of moral rigor. To be holy is to be “good” in an extraordinary, perhaps even superhuman, way. For me, this kind of perversion is exemplified by Bro. Wright, a cranky old man from the church my family attended when I was kid. Bro. Wright—it’s impossible to overstate how pleased I am that this happened to be his name—believed that he was “fully sanctified,” and so not only couldn’t sin but also couldn’t even be tempted to sin. Every December 31st, during what we called the “watch night” service, he would testify that if he had the year to live again he would do nothing differently. I don’t need to tell you that he was unbelievably distant, mean-spirited, condescending. No lie: he sat to the side of the sanctuary, in a metal folding chair, and presided over the services. In the end, not long before he died, he became so weary of dealing with the rest of us that he quit coming to church altogether.

Of course, Bro. Wright—or, more accurately, my memory of him—is a caricature. Still, I suspect that many of us recognize in this sketch an image we know. Perhaps we recognize something of ourselves? Regardless, it’s safe to say that if we’re thinking of the saintly life as one that leads away from the ugliness and inconvenience of life together, then we have utterly misunderstood the gospel. Sanctification moves us always deeper in, more toward the center of community, in the world as well as in the church.

The Fourth Gospel teaches us that Jesus is the one who prays for us to be where he is, interceding for us to have a home in his nearness to the Father. To be like Jesus, then, is to be “with God,” to abide “in the Father’s embrace,” and precisely in that place to open our lives for others, especially those most removed from God—the godless, the ungodly, the godforsaken. Christ prepares for us a place in the Father, the room he himself is. “I go to prepare a place for you,” he promises, “that where I am, you may be also.” He is the Father’s house, and as we become like Christ, we too become roomy, opened more and more for others to find their place in God through us. To be where Christ is, is to embody the mind of Christ, as Philippians 2 describes it; that is, to refuse to fixate on or take refuge in our personal relation to God, but instead to go on emptying ourselves, in myriad ways, in the unpretentious care of our neighbors and enemies, becoming obedient, day after day, to the cross we’re bound to bear.

The horizontal beam of this cross is the otherness, the strangeness, of our sisters and brothers, outside and inside the church, and all the difficulties their strangeness causes for us and for them. As Bonhoeffer says, “Only as a burden is the other really a brother or sister and not merely an object to be controlled.” The vertical beam is the otherness, the strangeness of the God whose ways are not our ways and whose thoughts are beyond our thoughts. Enduring this manifold strangeness, we identify ourselves with Christ in his intervening, atoning agony and just so find ourselves taking on his character. Look again at Hebrews 12. The holiness to which we are called, the holiness without which we cannot see the Lord, is a holiness we are called to make possible for others. “See to it,” the text says, “that no one fails to obtain the grace of God.” See to it that the weak are made strong, that the lame are healed. See to it that bitterness can take no root. See to it that Jacob and Esau live at peace.

Intercession, then, is the surest mark of holiness. Like Abraham, we intercede for Sodom—not only for God to spare their lives but also for God to forgive their sins. Like Moses and Aaron, we stand in the midst of the rebels—the very ones calling for our demise—and resist the divine judgment against them. Like Christ, even as we are dying, falling into the abyss of godforsakeness, we cry out for our oppressors’ forgiveness. “Father, forgive them; they do not know what they are doing.” A.W. Tozer famously said that the most important thing about us is what comes into our minds when we think about God. That’s not quite right. The most important thing about us is what comes into our hearts when we see the sins of our enemies. In the end, the sheep are known by how they see—and see to the needs of—the goats.

Finally, I want to return to the language of the “beauty” of holiness. In what ways is holiness beautiful? In just the same way that Jesus himself is beautiful. The beauty of holiness is the unrecognized, undesired beauty of the Suffering Servant who suffers for others’ salvation, his life utterly expended for theirs. As we become like him, we too will be despised, held in no account, as we, like and with him, bear others’ infirmities, carry their dis-ease, making their wounds our own, letting their iniquities fall upon our heads. Oppressed and afflicted, we will hold our tongues, and find ourselves again and again led like lambs to the slaughter. For his sake, we are sure to be killed all day long—and precisely in these moments to know ourselves to be “more than conquerors.” It is this beauty that will captivate the world, so that they’ll say of us, “they have been with Jesus.” By this the world will know that we are his disciples. What more could we want or ask for?

[Chris’ recent book, Toward a Pentecostal Theology of the Lord’s Supper: Foretasting the Kingdom, was reviewed here]

Rajasthani Red Meat

This recipe, based on Madhur Jaffrey’s from her At Home with Madhur Jaffrey: Simple, Delectable Dishes from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, is a real hoot at our place.

This recipe, based on Madhur Jaffrey’s from her At Home with Madhur Jaffrey: Simple, Delectable Dishes from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, is a real hoot at our place.

When this dish is served in the Rajasthan desert region of India, its colour, coming mainly from ground hot chillies, is a fiery red. In the recipe below, I have moderated the heat by mixing cayenne pepper with more calming paprika for those who might prefer a milder curry. Fresh red paprika is good too if you are chasing a more traditional colour. My own preference, however, is to go with the Kashmiri chilli powder.

It is generally served with Indian flatbreads, but is just as good served with rice. A calming green, such as spinach or Swiss chard, could be served on the side as well, as can plain yoghurt.

Serves 4–6

Ingredients

¼ cup olive or coconut oil

Two 7cm cinnamon sticks

6 whole cloves

10 green cardamom pods

1 large red onion, chopped finely

2 teaspoons very finely grated peeled fresh ginger

4 garlic cloves, crushed to a pulp

1 tablespoon ground coriander

1kg stewing lamb, preferably from the shoulder, cut into big (6-8cm) cubes. (Alternatively, you can use stewing beef.)

1½ teaspoons salt, or to taste

1 teaspoon cayenne pepper

2 tablespoons Kashmiri chilli powder

3 tablespoons chopped fresh coriander

Method

Pour the oil into a large, heavy pan and set over medium-high heat. When hot, put in the cinnamon sticks, cloves, and cardamom. Let the spices sizzle until the aroma begins. Add the onions. Stir and fry until they turn a reddish brown. Add the ginger, garlic, and coriander. Stir for a minute. Add the lamb/beef, salt, cayenne, and chilli powder. Stir for 3–4 minutes. Now add 4 cups water and bring to a boil. Cover, turn heat to low, and simmer for about an hour 1, stirring occasionally. Then remove the lid, and continue simmering on very low heat for between 2 and 6 (or more) hours, or until the meat is tender and the gravy is at your desired thickness. Sprinkle the coriander over the top when serving. Enjoy with a beer and with some after-dinner yoga.

Do you love me?

Stanley Hauerwas is always worth listening to. Here he is preaching on Jesus’ words, ‘Do you believe in love me?’, at the recent closing convocation at Duke Divinity School:

The Māori Prophets

Māori Television is running what promises to be a fascinating seven-part series on The Māori Prophets. Here’s the blurb:

Māori Television is running what promises to be a fascinating seven-part series on The Māori Prophets. Here’s the blurb:

The Māori prophets are an incredible part of our nation’s history. The Prophets is a fascinating seven-part series presented by Anglican Priest and historian, Reverend Hirini Kaa.

From the time the Bible began to be widely translated into te reo Māori in the 1830s through to the middle of the 20th century, the show chronicles the lives, beliefs and social conditions that saw these messianic figures rise from within Māori communities.

Starting with leaders like Papahurihia, the first prophet to draw on Māori and Christian doctrine, emerging with a new form of traditional Māori spirituality to more well-known prophets (Te Kooti, Te Whiti and Tohu and Ratana), The Prophets unveils an incredible part of our nation’s history.

Thus far, only the first episode in the series has been aired. It – and presumably, in time, those episodes forthcoming – can be viewed here.