Author: Jason Goroncy

Richard Flanagan on Syria’s great exodus

The CEO of World Vision Australia, the Rev Tim Costello, recently invited Richard Flanagan and Ben Quilty to visit Lebanon, Greece, and Serbia, and so to see (and smell, and taste, and hear … and feel) first hand something of the Syrian refugee crisis. It was a smart move.

Richard wrote up something of that experience for the Guardian. (Apparently, a fuller account is coming. I very much look forward to reading it.) And then earlier this week, he was interviewed by Richard Fidler. The interview is deeply moving, and witnesses to the paradoxes of the human condition – from the deep grace of human hospitality and of hope’s desperate determinations, to our ugliest forms of opportunism, both economic (the story of the life death-jackets was outrageous) and political – the disgrace of using refugees (and other already-vulnerable persons, for that matter) as political bargaining chips rather than leaning unreservedly into fuller implications of the fact that, in Flanagan’s words, ‘that terrible river of the wretched and the damned flowing through Europe is my family. And there is no time in the future in which they might be helped. The only time we have is now’.

You can listen to the interview here.

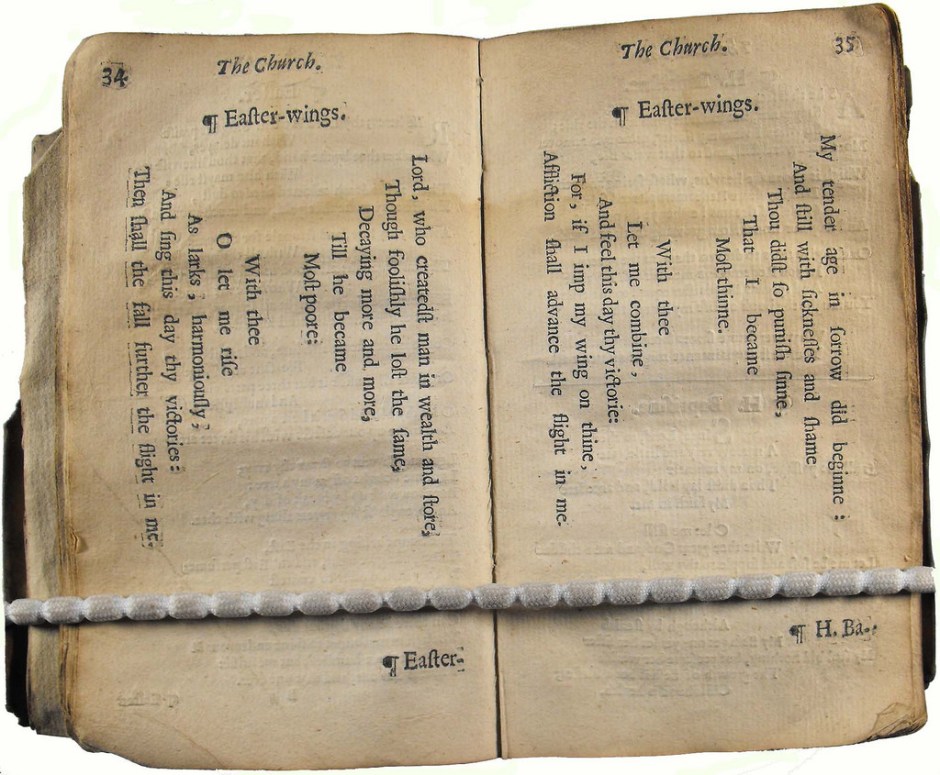

[Image: Lynsey Addario/Guardian]

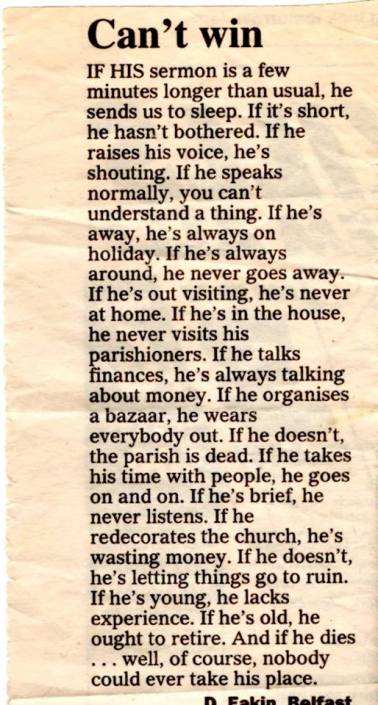

Pastors can’t win

This all seems to ring true for women clergy too, for whom I’m sure that a number of further statements might be added. I’m not confident, brave, or stupid enough to speak for them, but invite their comments below.

On a more serious note, I’m really glad that pastors can’t win. Their job is, after all, meant to be impossible.

[Image: via Peter Weeks on Facebook]

Who is Jesus?

This coming semester at Whitley College, I’ll be teaching a unit called Who is Jesus?

Here’s a little about it:

I’m really looking forward to teaching this unit – alongside one on my other favourite JC, Johnny Calvin – and to the insights that emerge as my students and I engage with the following texts, among others:

I. WHO IS CHRIST FOR US TODAY? ON THE QUESTS FOR THE HISTORICAL JESUS

- Stephen E. Fowl, ‘Reconstructing and Deconstructing the Quest for the Historical Jesus’, Scottish Journal of Theology 42 (1989), 319–33.

- Thomas P. Rausch, Who is Jesus?: An Introduction to Christology (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2003), Chapters 1 and 2.

II. SECOND TESTAMENT CHRISTOLOGY – INTERCHANGE, UNION, AND RESURRECTION: ST PAUL’S APOCALYPTIC CHRIST

- Douglas A. Campbell, ‘Christ and the Church in Paul: A “Post-New Perspective” Account’, in Four Views on the Apostle Paul, ed. Michael F. Bird (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012), 113–43.

- Louis Martyn, ‘The Apocalyptic Gospel in Galatians’. Interpretation 54, no. 3 (July 2000), 246–66.

III. SECOND TESTAMENT CHRISTOLOGY – PORTRAITS OF BELIEF

- Gerald O’Collins, ‘The Jewish Matrix’, in Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 21–43.

- Francis Watson, ‘The Quest for the Real Jesus’, in The Cambridge Companion to Jesus, ed. Markus Bockmuehl (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 156–69.

IV. EARLY SETTLEMENTS – I

- Gregory of Nazianzus, ‘To Cledonius the Priest against Apollinarius (Ep. CI)’, in A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series. Volume 7: S. Cyril of Jerusaelm, S. Gregory Nazianzen, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Edinburgh/Grand Rapids, MI: T&T Clark/Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1989), 439–43.

- Irenæus, ‘Against Heresies’, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325. Volume I: The Apostolic Fathers – Justin Martyr – Irenæus, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Edinburgh/Grand Rapids, MI: T&T Clark/Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1993), III.16–22 (pp. 440–55).

- Tertullian, ‘Against Praxeas; in which he defends, in all essential points, the doctrine of the Holy Trinity’, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325. Volume III: Latin Christianity: Its Founder, Tertullian, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Edinburgh/Grand Rapids, MI: T&T Clark/Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1993), Chapters 27–30 (pp. 623–27).

V. EARLY SETTLEMENTS – II

- Athanasius, Athanasius on the Incarnation: The Treatise De Incarnatione Verbi Dei, trans. The Religious of C. S. M. V., 2nd ed. (London: A. R. Mowbray, 1953), 25–64.

VI. CHRIST IN CELLULOID

- The film Ordet, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer.

- Robert Barron, ‘Christ in Cinema: The Evangelical Power of the Beautiful’, in The Oxford Handbook of Christology, ed. Francesca Aran Murphy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 475–87.

VII. THE SAVING GOD

- Anselm, ‘Why God Became Man’, in Anselm of Canterbury: The Major Works, ed. Brian Davies and G. R. Evans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), I.xi–xxi, II.iv–xx (pp. 282–307, 317–54).

- John D. Zizioulas, ‘Biblical Aspects of the Eucharist’, in The Eucharistic Communion and the World, ed. Luke B. Tallon (London: T&T Clark, 2011), 1–38.

VIII. THE DYING GOD

- Eberhard Jüngel, God as the Mystery of the World: On the Foundation of the Theology of the Crucified One in the Dispute between Theism and Atheism, trans. Darrell L. Guder (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1983), 343–68.

- Karl Barth, The Humanity of God, trans. John Newton Thomas and Thomas Wieser (London: Collins, 1961), 37–65.

IX. THE RESURRECTED AND COMING GOD

- Hans W. Frei, The Identity of Jesus Christ: The Hermeneutical Bases of Dogmatic Theology, Expanded and updated ed. (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013), 140–50.

- Jürgen Moltmann, ‘The Resurrection of Christ: Hope for the World’, in Resurrection Reconsidered, ed. Gavin D’Costa (Oxford: Oneworld, 1996), 73–86.

- Rowan Williams, Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel, 2nd ed. (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2002), 68–90.

X. GOD IN THE GALLERY

- Jeremy Begbie, ‘Christ and the Cultures: Christianity and the Arts’, in The Companion to Christian Doctrine, ed. Colin E. Gunton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 101–18.

- Robin M. Jensen, ‘Jesus Up Close’, Christian Century 120, no. 19 (2003), 26–30.

- Lawrence S. Cunningham, ‘Christ in Art from the Baroque to the Present’, in The Oxford Handbook of Christology, ed. Francesca Aran Murphy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 506–16.

XI. CHRIST IN THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD: CONTEXTUAL CHRISTOLOGIES

- Benjamin Myers, ‘“In his own strange way”: Indigenous Australians and the Church’s Confession’, Uniting Church Studies 16, no. 1 (2010), 39–48.

- Stuart Piggin, ‘Jesus in Australian History and Culture’, in Mapping the Landscape: Essays in Australian and New Zealand Christianity: Festschrift in Honour of Professor Ian Breward, ed. Susan Emilsen and William W. Emilsen, American University Studies (New York, NY: Peter Lang, 2000), 150–67.

- The Rainbow Spirit Elders, Rainbow Spirit Theology: Toward an Australian Aboriginal Theology, 2nd ed. (Hindmarsh: ATF Press, 2012), 55–74.

- Stanley Jedidiah Samartha, ‘Indian Realities and the Wholeness of Christ’, Missiology 10, no. 3 (1982), 301–17.

XII. THE FINALITY OF JESUS CHRIST IN A PLURALIST WORLD?

- Gavin D’Costa, ‘Christ, the Trinity and Religious Plurality’, in Christian Uniqueness Reconsidered: Myth of Pluralistic Theology of Religions, ed. Gavin D’Costa, Faith Meets Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1990), 16–29.

- John Hick, ‘Christology in an Age of Religious Pluralism’, Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 35 (1981), 4–9.

If you’re keen to know more, it’s not too late to enrol ;-) The unit can be taken at either undergraduate or postgraduate level, as well as online (at UG or PG level) from anywhere the World Wide Web has reached.

Alan P. F. Sell (1935–2016): A Service of Thanksgiving

Dr Karen Sell has asked if I might make public the details below about the thanksgiving service being arranged following the death of Alan Sell:

You are warmly invited to A Service of Thanksgiving for the Gospel on occasion of the death of Alan Philip Frederick Sell at The Church of Christ the Cornerstone Saxon Gate Milton Keynes on Thursday March 3rd 2016 at 2.15 pm. Refreshments will follow the Service. If so wished donations may be sent to Willen Hospice, Milton Road, Milton Keynes, MK15 9AD.

Alan Philip Frederick Sell (1935–2016): Per Crucem ad Lucem

I am grieved to learn (via Kim Fabricius) that my dear friend Alan Sell, who had been quite unwell for some time now, has died. In an email sent to United Reformed Church ministers (current and retired), Helen Lidgett (Synod Clerk, East Midlands Synod) stated:

I am grieved to learn (via Kim Fabricius) that my dear friend Alan Sell, who had been quite unwell for some time now, has died. In an email sent to United Reformed Church ministers (current and retired), Helen Lidgett (Synod Clerk, East Midlands Synod) stated:

I am deeply saddened to report the death of Rev Professor Alan Sell. He died peacefully, content, and with great dignity at 9.00 pm on Sunday February 7th in Willen Hospice in Milton Keynes. Details of the Green Burial and Thanksgiving Service will be forwarded shortly.

Our thoughts and prayers are with Alan’s wife, Karen and their family.

Alan’s qualifications were: BA; BD; MA; DD; DLitt; PhD; HonDD; Hon DTh; FSA FRHistS; He was ordained in 1959 and had a very fruitful and world-wide ministry:

1959–1964: Sedbergh & Dent

1964–1968: Hallow, Worcester & Ombersley

1968–1983: Theological Lecturer & Professor in UK

1983–1987: Theological Secretary WARC

1988–1992: Theological Lecturer & Professor in Canada

1992–2001: United Theological College Aberystwyth

In retirement he continued to write and contribute to theological debate, including a valuable contribution to the discussion on the marriage of same sex couples at East Midands Synod in March 2015.

Alan was a good friend, and a wonderful encourager to me. I shall miss him and our frequent correspondences very much. Already, the world certainly feels poorer without him.

In pace requiescat et in amore Alan.

℘

You can read my reviews of some of Alan’s work here:

- Hinterland Theology: A Stimulus to Theological Construction (Paternoster, 2008)

- Nonconformist Theology in the Twentieth Century (Paternoster, 2006)

- The Theological Education of the Ministry: Soundings in the British Reformed and Dissenting Traditions (Pickwick, 2013)

- edited with Anthony R. Cross. Protestant Nonconformity in the Twentieth Century (Paternoster, 2003)

Living betwixt and between muddle and ambiguity

‘Royal Cave’, Buchan Caves Reserve. © Jason Goroncy, 2016

Over these past days, I have been reminded again that at our best, to be human, and to be human community, is to live betwixt and between muddle and ambiguity. We are, unavoidably, marked by profound inconsistencies and misdirected hopes. We are an enigma – even, and perhaps especially, to ourselves.

A few months ago, the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams gave an outstanding lecture on what George Orwell can teach us about the language of terror and war. In that lecture, he drew not only upon Orwell’s work but also upon that of the Trappist monk, poet, and social activist Thomas Merton, and he argued that each in their own way were concerned with the power and the misuse of language. Williams suggested that ‘our current panics about causing “offence” are, at their best and most generous, an acknowledgement of how language can encode and enact power relations’.

Certainly, the spirit of the age in which we live is characterised by efforts to entrench unquestionable power, power that makes unwelcome voices of dissent, and which feels little or no responsibility to those who do not serve its own proximate interests.

According to Williams, our thoughts and wrestles and debates about those questions which really matter for the flourishing of life often expose ‘a deep unwillingness to have things said or shown that might profoundly challenge someone’s starting assumptions. If there is an answer to this curious contemporary neurosis, it is surely not to be found in the silencing of disagreement but rather in the education of speech: how is unwelcome truth to be told in ways that do not humiliate or disable? And the answer to that question is inseparable from learning to argue – from the actual practice of open exchange, in the most literal sense “civil” disagreement, the debate appropriate to citizens who have dignity and liberty to discuss their shared world and its organisation and who are able to learn what their words sound like in the difficult business of staying with such a debate as it unfolds’.

Isn’t that one of the reasons that we place ourselves in communities of faith? I often tell my children that one of the main reasons we go to church is so that we can learn and practice loving people that we don’t really like that much – people who irritate us, people who we find odd and who we’d never be seen dead with otherwise, people who frustrate us and hurt us and disappoint us. We belong to the church because that is how we hope to learn the truth that is required for our being truthful about ourselves and about one another. What is the Christian community if it is not a unique training ground for learning the lessons of being the kind of community that God intends for all humanity – for learning that to be truly human is to belong to and to relate to and to do life with those who are other than ourselves, those whom God has joined together?

And so we eat and drink – not only with friends, but also with strangers, with enemies and with betrayers … and with our own inner demons. For that is the context in which Christ makes himself available to us.

Prayers of a Secular World: a review

Prayers of a Secular World. Edited by Jordie Albiston and Kevin Brophy; introduction by David Tacey. Carlton South: Inkerman & Blunt, 2015. 160pp, ISBN: 978-0-9875401-9-5.

Prayers of a Secular World. Edited by Jordie Albiston and Kevin Brophy; introduction by David Tacey. Carlton South: Inkerman & Blunt, 2015. 160pp, ISBN: 978-0-9875401-9-5.

Inkerman and Blunt recently published a new anthology of work, a relatively little book by an impressive range of some 80 mostly Antipodean poets, some very well known, others hardly at all. The collection, Prayers for a Secular World, was edited by Melbourne poets Jordie Albiston and Kevin Brophy, and is introduced, fittingly so, with a brief essay by David Tacey on the religious nature of secularism. The latter helps to orient the reader to some of the terrain they are about to enter.

In their call for submissions, the editors said that they were ‘looking for poems of wonder and celebration, poems that mark the cycle of the day – dawn, midday, evening, night – the seasons, the progression of planets, the evolution of weather; poems of becoming – first steps, first words, transitions, epiphanies and inspirations; poems of belief and of doubt, pleas for protection, poems of remembrance and blessing, of forgiveness and redemption, poems of gratitude’. Short of the sternest editorial policing, such an invitation almost guarantees, more than most edited collections I think, the kind of hotchpotch smorgasbord of aptitude evident in the volume’s final form. Still.

The book’s title – which echoes Donna Ward’s claim, in Australian Love Poems, that ‘poems are prayers of the secular world’ – appears, at first glance, to promote the somewhat late-Victorian idea that poets are the new priests. But the pages therein are marked by a welcome avoidance of such presumption, their words occupied with patterns of time and of place, of dying and of encountering the world anew, and with the sounds of landscapes mostly suburban, where the majority of its readers, no doubt, dwell and pass through. In a review published in The Australian, Geoff Page noted of the title: ‘They are certainly not be [sic] “prayers” in the intercessory sense but they are contemplative and very likely to widen and diversify the metaphysical sensibilities of all but the most hardened of fundamentalists – who, no doubt, already have their own (more limited) rewards in view’. This is a point worth repeating, especially perhaps for those uncomfortable, in Tacey’s words, with the notion that ‘the transcendent doesn’t happen elsewhere, apart from the world, but is a dimension of the world’. Still, the publisher’s description of the book as ‘a meditation on living in a post-religious world’ strikes me as very odd – odd not only as a sketch of the book’s content, but also odd in terms of its assessment of things. Observers of the cultural landscape of our day might well enquire what world exactly is being spoken of here.

There is, for many, the perennial temptation to will oneself into a kind of authenticity. Such efforts are an expression of a romanticism that either refuses or forgets to weave into the solidest realities a knowledge of its loss. The result is, as the poet Christian Wiman has observed, a ‘soft nostalgia’. There are here, happily, a good number of notable exceptions to what might otherwise be merely another unwelcome example of such, of groping disorientated by a handful of tamed Emersonian ghosts trying to iron out the highs and lows of life apparently naïve to the view that our being of dust does not equate to an uncritical defence of some pathetic form of natural theology. In this volume, poems by Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Andrew Lansdown, Fiona Wright, Robyn Rowland, Debi Hamilton, Ron Pretty, Anne Elvey, Michelle Cahill, and David Brooks, for example, serve this end particularly well. So do, I think, these two contributions:

‘Da Barri Barri Bullet Train’, by The Diwurruwurru Poetry Club with Mista Phillip

we bin get up with mista an habim gooda one feed

we bin jumpin da mudika

an millad bin go lunga bush

mimi an kukudi bin come too

an dey bin singim kujika

dey bin learnim us mob

for sing im kujika

we likim learn for sing us mob kujika

wen us mob bin lyin down in da darkes

darkest night I bin look da barri barri

e bin movin really really like da bullet train

I bin hold ma mimi really tight

da fire us mob bin make next ta millad mob

poking tongue like a big one king brown

an millad mob listen noise one side na water

must e bin da buffalo drinkin water

den us bin listen da croc bin snap da buffalo

da gnabia out there too

an he bin make us mob so frightn

but ma mimi bin sing out

hey you mob stop all da noise

ma mimi bin start to sing

da song na us mob country

sing in da old language

dem old people did sing

an make millad mob so shiny an strong

an I bin lyin da listen na mimi

I bin feel really really safe

den I musta bin go sleep

And

‘Eucalyptus Regnans’, by Meredi Ortega

for Brandi

that was some fiery trajectory you took, moving to Kinglake

to be among giants and clouds

I recall you dying once before

…….. .. run down at the crossing, going home for lunch

but you’re on Yea oval, among the nightied and discalceate

and you’re okay

road posts gone

all delineators and signs, the way forward and way back

…….. ..only black stags, ash deafening

one charred fence post

and your old weatherboard like a kind of gloating, it falls to you

…….. ..to be the lucky one

better to believe in regnans than luck, they have what it takes

martyrdom, lofty sentiments

…….. ..all crown and nimbus and resurrection

up on the mountain, no one knows if lyrebirds

are mimicking silence

…….. ..volunteers go into the wasteland, leave songs out

musk and fern and siltstone tunes

it rains and then some

…….. ..and the green is giddying

stags wash white, their millioned saplings serry

…….. ..knit roots, squeeze out the other then each other

ashes move up the escarpment and up

to the yellow-raddled cockatoo, yellow-eyed currawong, to the sun

and you are in the very dawn of things

… believing in God’s love

Here’s a wonderful confession from Thomas Merton, which even in its brevity dares to say more than we can really know this side of the dirty mirror:

Here’s a wonderful confession from Thomas Merton, which even in its brevity dares to say more than we can really know this side of the dirty mirror:

Automatic and compulsive routines that are simply silly – and I don’t take them seriously. All the singing, the “speaking in tongues,” etc. Funny. I see how easily I could go nuts and don’t especially care. I see the huge flaws in myself and don’t know what to do about them. Die of them eventually, I suppose, what else can I do? I live a flawed and inconsequential life, believing in God’s love. But faith can no longer be naïve and sentimental. I cannot explain things away with it. Need for deeper meditation. I certainly see more clearly where I need to go and how (surprising how my prayer in community had really reached a dead end for years and stayed there – fortunately I could get out to the woods and my spirit could breathe). Still, Gethsemani too has to be fully accepted. My long refusal to fully identify myself with the place is futile (and identifying myself in some forlorn and lonesome way would be worse). It is simply where I am, and the monks are who they are: not monks but people, and the younger ones are more truly people than the old ones, who are also good in their own way, signs of a different kind of excellence that is no longer desirable in its accidentals. The essence is the same.

Renounce accusations and excuses.

– Thomas Merton, Dancing in the Water of Life: Seeking Peace in the Hermitage, ed. Robert E. Daggy, The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume 5: 1963–1965 (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1998), 328.

With thanks to Mary Luti for drawing my attention to some of these words.

A little commendation for The Givenness of Things

I want to commend Marilynne Robinson’s recent book The Givenness of Things.

The result of this collection of wise and intelligent essays on profoundly human themes, proclivities, and experiences – like poverty, theology, freedom, randomness, fear, fads, greed, faith, science, and alarmism, breathed through with decent doses of Shakespeare, Calvin, Locke, and Saints Matthew and Luke, and marked by a remarkably high christology – is a perspicacious map which assists those of us living in and with Western cultures to read better the signs of the times, and to live better orientated towards those things that will outlast all else. A gift, from one who on her next birthday will be seventy.

I read large amounts of this book while sitting by two kangaroos – a big one, and a little one. They seemed to enjoy my company as much as I did theirs, and that of this book. And nearby hung this sign, another telling commentary on the state of things:

Rowan Williams’s lectures on ‘Christ and the Logic of Creation’

Rowan Williams has begun delivering his series of public lectures on the subject of ‘Christ and the Logic of Creation’. This series of Hulsean Lectures traverses the following ground:

Rowan Williams has begun delivering his series of public lectures on the subject of ‘Christ and the Logic of Creation’. This series of Hulsean Lectures traverses the following ground:

12 January 2016: A Mediaeval Excursion: Aquinas’s Christology and its aftermath.

19 January 2016: Defining the Problem: from Paul to Augustine.

26 January 2016: Logos and logoi: A Byzantine breakthrough.

2 February 2016: The Last of the Greek Fathers? An unfamiliar Calvin.

9 February 2016: Centres and Margins: Bonhoeffer’s Christ.

16 February 2016: ‘In Whom all Things Cohere’: Christ and the logic of finite being.

And while my attention is turned towards Cambridge, I will also mention Ian McFarland‘s recent Inaugural Lecture. The subject: The Crucial Difference: For a Chalcedonianism without Reserve.

The Eucharist ‘puts an end to every war waged by heavenly and earthly enemies’

Francisco de Zurbarán, Agnus Dei (1635–40). Prado Museum, Madrid.

A good read here from William Cavanaugh. Here’s a snippet:

True sacrifice can never be the immolation of a victim, making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country. True sacrifice is nothing other than the unity of people with one another through the participation in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. Christ’s sacrifice reverses the idea that one must achieve domination over the enemy to achieve unity. Christ instead takes on the role of victim, absorbs the violence of the world instead of deals it out, and thereby offers a world in which reconciliation rather than violence can hold sway.

This is why the Eucharist is the antidote to war for Augustine. In the Eucharist, the whole economy of scarcity and competition that leads to war is done away with. Augustine makes clear that God does not need to be appeased as the Roman gods do. God is abundance, not lack, so participation in God’s life in the body of Christ does away with competition over scarce goods among people. True sacrifice is unity, and true unity is the participation of the human community in God’s life …

War depends on dividing up the world in such a way that some are excluded from this drama. We prefer to make rigid distinctions between friend and enemy, between our virtue and their depravity. We are thereby licensed to ignore the role our own interventions in their world may have had in stirring up their animosity toward us. When faced with war, we might do better to respond first in a penitential key. At the beginning of World War II, the Catholic Worker newspaper ran a headline: “We Are Responsible for the War in Europe.”

Christians who embrace non-violence are often accused of unrealistically trying to impose a perfectionist ethic on mere sinful human beings. I find it remarkable that travelling to the other side of the world to shoot people is considered somehow everyday and mundane, while refraining is considered impossibly heroic.

The reason we should reject violence is not from a prideful conviction that we are the pure in a world full of evil. The gospel call to non-violence comes from the realization that we are not good enough to use violence, not pure enough to direct history through violent means. Peacemaking requires not extreme heroism, but a humble restraint in identifying enemies, and an everyday commitment to caring for members of one’s body in mundane ways: feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and imprisoned, all of whom, Jesus says, are Jesus himself.

Christian non-violence imitates Jesus’s nonviolence, but it also participates in Jesus’s self-emptying into sinful humanity, his sharing in the brokenness of the world. It is this peacemaking that we enact in sharing the broken bread of the Eucharist.

Seeking descriptions of baptism in modern literature

My friend Alison is compiling a set of 40 short readings for Lent (I’ve posted a few of my own over the years), each of which is about the experience of baptism. She is especially keen to find descriptions of baptism in modern literature. So far, she has readings from Wendell Berry, Sara Miles, Marilynne Robinson, Vincent Donovan, Stanley Hauerwas, Giovanni Guareschi, Martin Luther King, Jr., William Kloefkorn, and others, including some from Dr Luke’s Book of Acts. She is also considering readings from Annie Dillard, Barbara Taylor Brown, Annie Lamott, Langston Hughes and others.

My friend Alison is compiling a set of 40 short readings for Lent (I’ve posted a few of my own over the years), each of which is about the experience of baptism. She is especially keen to find descriptions of baptism in modern literature. So far, she has readings from Wendell Berry, Sara Miles, Marilynne Robinson, Vincent Donovan, Stanley Hauerwas, Giovanni Guareschi, Martin Luther King, Jr., William Kloefkorn, and others, including some from Dr Luke’s Book of Acts. She is also considering readings from Annie Dillard, Barbara Taylor Brown, Annie Lamott, Langston Hughes and others.

Alison is looking for suggestions for additional readings, particularly those from Indigenous, Asian, or African writers.

So, any suggestions folks?

Some more perspectives on whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God

The Syrian Orthodox Church and the Omar Mosque, Old Town, Bethlehem, Palestine.

Two very constructive contributions to the discussion birthed from recent events at Wheaton College:

- Robert Priest, Professor of International Studies and Professor of Mission and Anthropology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, is concerned ‘over the way Wheaton [College] has framed the issues, over the repercussions of this for Christian witness, and over the failure to include missiologists and missionaries as interlocutors’. By way of response, he invited a number of evangelical and other respected missiologists and missionaries – those, in other words, whose insights have been mostly tragically absent in this discussion – ‘to write short essays addressing the following question: “What are the missiological implications of affirming, or denying, that Muslims and Christians worship the same God?”’ The result is a very helpful and much-welcomed resource, this ‘Occasional Bulletin’ from The Evangelical Missiological Society (EMS).

- The Australian theologian Geoff Thompson, of Pilgrim Theological College, has posted ‘an observation, some other questions, a concern, and a personal reflection’ here.

I also really appreciated this brief and timely reflection from Matthew Milliner (of Wheaton College), delivered at the Islamic Center of Wheaton.

I commend these resources to you. And if you, dear readers, come across any other such resources on this subject, you are encouraged to draw attention to them in the comments box below.

[Image: Palden Jenkins]

The Jews of Venice

The December edition of National Geographic includes a fascinating little read, and some great photos too by Fabrizio Giraldi, on Venice and its being home to the world’s oldest Jewish ghetto, at 500 years.

Baptists and life in covenant

Paul Fiddes has written a nice little reflection on the nature of covenant and how it relates to Baptist ecclesiology. Here’s a section:

Paul Fiddes has written a nice little reflection on the nature of covenant and how it relates to Baptist ecclesiology. Here’s a section:

It is essential to realise that this covenant is not a legal contract. The ‘way’ in which covenant partners walk can only be one of mutual trust. This is where Baptists have given an insight to the universal church which is a true gift. In the local congregation, covenanted together, all the members ‘watch over’ each other, and this ‘oversight’ happens in the church meeting as they seek to find the mind and purpose of Christ for them. At the same time, Baptists have always believed that Christ calls some of these members to exercise ‘oversight’ (or a ‘watching over’) in a spiritual leadership of the congregation. Among Baptists there is no legal provision, no church law, which regulates the relation between these two forms of ‘oversight’, the one corporate and other personal. Congregations must therefore learn to live in the bonds of trust between the people and their ministers. Oversight flows to and fro freely between the whole congregation and its spiritual leaders.

In the same way, oversight flows to and fro between the local congregation and the association of churches. The single congregation lives in a covenant made by Christ, and Christ is present among them to make his purpose known. The congregation is his body, where Christ becomes visible in the world today. This is why the congregation has ‘freedom’ to make decisions about its life and mission, and cannot be coerced or imposed upon by any church authorities outside it. The congregation is not ‘autonomous’, which means ‘making laws for itself’. Christ makes its laws, and the church has the freedom and responsibility to discern his ways. It is free because it is ruled only by Christ.

But Christ also calls local congregations together into covenant, in association. Where churches are assembled through their representatives, there too Christ is present, there he becomes visible to the world in the body of his people, there his mind can be known through the help of the Holy Spirit. Local congregations are thus ‘interdependent’, needing each other’s spiritual gifts and understanding if they are to share in God’s mission in the world.

Yet in the covenant principle there is no legal contract, only the way of trust. In their search for the mind of Christ the local church meeting must listen to what the churches say as they seek to listen to Christ together. It must take with complete seriousness the decisions made at an association level, and will need good reason not to adopt them for itself. But in the end it has freedom to order its own life as a covenant community which stands under the rule of Christ. It needs the insights of other churches to find the mind of Christ, but then it has the freedom to test whether what is claimed to have been found is truly his mind. It might feel called to make a prophetic stand on some issue, and will stand under the judgment only of Christ as it does so.

Other churches may think that this covenantal approach of mutual trust is hopelessly impracticable, and that it would be better to regulate the relation between people and clergy, between churches and diocese or province. Baptists have learned over the years to live with the risks of trust and love. Here there is plenty of opportunity for muddles, mistakes and frustrations, but also room for all to flourish.

You can read the full piece here.

On believing and confessing the one God, ‘although in different ways’

Ben Myers’s delightful and constructive offering yesterday to the discussion of whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God reminded me of Pope Gregory VII’s letter to Anzir, the King of Mauretania. In that letter, penned in 1076 (and so in the period between John of Damascus and Paul of Antioch, Ben’s two subjects), Gregory suggests that Christians and Muslims do indeed worship the same God, ‘although in different ways’. (Implicitly, he is doing what many recent commentators, in their noble efforts to seek intellectual coherence, have failed to do; namely, to indicate, albeit subtly, a distinction between ontological and epistemological claims vis-à-vis God.)

Ben Myers’s delightful and constructive offering yesterday to the discussion of whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God reminded me of Pope Gregory VII’s letter to Anzir, the King of Mauretania. In that letter, penned in 1076 (and so in the period between John of Damascus and Paul of Antioch, Ben’s two subjects), Gregory suggests that Christians and Muslims do indeed worship the same God, ‘although in different ways’. (Implicitly, he is doing what many recent commentators, in their noble efforts to seek intellectual coherence, have failed to do; namely, to indicate, albeit subtly, a distinction between ontological and epistemological claims vis-à-vis God.)

So Gregory:

God, the Creator of all, without whom we cannot do or even think anything that is good, has inspired to your heart this act of kindness. He who enlightens all people coming in to the world [Jn 1.9] has enlightened your mind for this purpose. Almighty God, who desires all people to be saved [1 Tim 2.4] and none to perish, is well pleased to approve in us most of all that besides loving God people love others, and do not do to others anything they do not want to be done unto themselves [Mt 7.12]. We and you must show in a special way to the other nations an example of this charity, for we believe and confess one God, although in different ways, and praise and worship him daily as the creator of all ages and the ruler of this world. For the apostle says: ‘He is our peace who has made us but one’ [Eph 2.14]. Many among the Roman nobility, informed by us of this grace granted to you by God, greatly admire and praise your goodness and virtue … God knows that we love you purely for his honor and that we desire your salvation and glory, both in the present and in the future life. And we pray in our hearts and with our lips that God may lead you to the abode of happiness, to the bosom of the holy patriarch Abraham, after long years of life here on earth. (Cited in J. Neuner and J. Dupuis, eds., The Christian Faith in the Documents of the Catholic Church. Bangalore: Theological Publications in India, 1982, 276–77. Slightly modified for gender inclusivity and correction of one of the biblical references.)

The backstory to this letter – and there’s always a backstory! – is that Anzir had sent Gregory a gift which included the freeing of some Christian (?) prisoners. Gregory’s response was this letter sent with a delegation as a sign of friendship, and the remarkable invitation to live together in the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount.

Bruce McCormack too has weighed into the recent conversation with a very helpful piece.

(And for those who may be interested, I touched briefly on the subject a few years ago in this post.)

Jesus and film

I’m trying to settle on a film – just one – to include in my upcoming christology unit. (I often include at least one film per unit.) So far, I’ve shortlisted the following:

I’m trying to settle on a film – just one – to include in my upcoming christology unit. (I often include at least one film per unit.) So far, I’ve shortlisted the following:

- Au Hasard Balthasar (Bresson)

- Calvary (McDonagh)

- The Last Temptation of Christ (Scorsese)

- Magnolia (Anderson)

- Son of Man (Dornford-May)

- Offret (Tarkovsky)

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Forman)

- Romero (Duigan)

- Waiting for Godot (Beckett)

(That’s right, neither The Life of Brian, nor Miss Congeniality, nor Jesus of Montreal, nor The Karate Kid, nor Red Sonja, nor The Gospel According to St. Matthew, nor Taxi Driver quite made this year’s shortlist.)

At the moment, the frontrunners for me are Beckett’s Godot and Tarkovsky’s Offret, but I’m keen to crowdsource any other suggestions.

‘Journey of the Magi’

‘A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

and running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arriving at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you might say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

– T. S. Eliot, ‘Journey of the Magi’, in Collected Poems, 1909–1962 (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), 109–10.

[Image: Robert Perry, ‘Three Trees at Sunset, Fontainebleau Forest’]

Hope is the strangest protest

The poet and novelist George Mackay Brown is well-known for his love of place, and for his laments about their destruction with the advent of stuff like concrete, plastic bottles, portable transistor radios, and what he describes as the ‘menace of cars’, indeed with all signs of industrialization.

The poet and novelist George Mackay Brown is well-known for his love of place, and for his laments about their destruction with the advent of stuff like concrete, plastic bottles, portable transistor radios, and what he describes as the ‘menace of cars’, indeed with all signs of industrialization.

In a piece penned for The Orcadian and published on 23 March 1972, he (again) recounts feelings of deep grief about the prevalence of contaminants – oil slicks and junk – that he finds on his sojourns along the coast of his beloved island home. But the piece concludes on a different note:

We must have faith that somewhere, deep down at the very roots and sources of life, there is an endless upsurge of health and renewal. (If there were not, the earth would have shriveled like a rotten apple millenniums since.) A hundred years ago the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, troubled by the pollution of industrial England, consoled himself with the certainty that ‘there lives the dearest freshness deep down things …’. We can only hope that that primal unsullied source will be strong enough to wash away the frightful poisons that men are pouring into the air and earth and oceans every hour of the day and night. So, nowadays, when I take an afternoon walk around the coast, I am not offended any more by the empty sauce bottles and syrup tins on the rocks below. They seem to be simply human friendly objects. The freshness of nature, that lives ‘deep down things’, passes over them, and they are gone.

Hope is the strangest – and the most unbelievable – protest.

[Image: source]