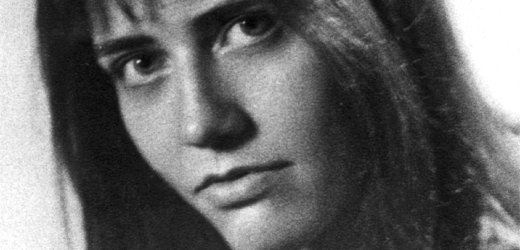

Many of my earliest memories seem to have grandparents in the frame, and many owe their origin to Babcia’s photo album – that collection of somewhat faded, browning and out-of-focus snapshots, many with heads carelessly decapitated, photos whose value as art is radically juxtaposed in comparison to their value as icons of sentiment and as a record of a story of her life; or, more accurately, the narrative of all our lives. For Babcia was the kind of person whose life was intricately and inseparably woven into our own. Indeed, in Babcia we have been graced with one whose identity is wrapped up in ours, whose identity as a sister, wife, mother, grandmother, matriarch, friend and neighbour was more voluminous than any identity that society might wish to allocate to her, but in whom blood was always thicker than water, even when conventional wisdom might desire otherwise.

Many of my earliest memories seem to have grandparents in the frame, and many owe their origin to Babcia’s photo album – that collection of somewhat faded, browning and out-of-focus snapshots, many with heads carelessly decapitated, photos whose value as art is radically juxtaposed in comparison to their value as icons of sentiment and as a record of a story of her life; or, more accurately, the narrative of all our lives. For Babcia was the kind of person whose life was intricately and inseparably woven into our own. Indeed, in Babcia we have been graced with one whose identity is wrapped up in ours, whose identity as a sister, wife, mother, grandmother, matriarch, friend and neighbour was more voluminous than any identity that society might wish to allocate to her, but in whom blood was always thicker than water, even when conventional wisdom might desire otherwise.

And what story does that family photo album bear witness to? It gives us only hints of what Babcia’s life was like before she arrived at Cowra and then at Bonegilla migrant centre on these shores. From only a handful of photos, and a scattering of various stories have we been able to cut and paste together some image of what her life was like before her two sons arrived on the scene. I shall not dwell on that here, but only mention her birth on 16 April 1926 in Woronez, Russia, where she was also baptised, and her years as a farm worker in Selkentrop (a village still as tiny as it is rural) in the early 1940s in a Europe in the grip of fear, and of her falling in love with the gentle human being – Janek Goronze – who would be her husband until 1982. Birthing children and the turn Down Under created the opportunity for Babcia and Dziadek, together with many who would become their friends, to begin, as it were, again. One way that this beginning was celebrated was through countless parties and an abundance of food rarely known in a past life they all seemed intent on forgetting.

The photos bear witness to the fact that in those earlier days, when her strength was greater and her zest for life more uninhibited than it was in recent years, she enjoyed outings to roadside picnic grounds and rydzed-forests well-trodden by members of the Polish community, and even more adventurous expeditions to far-flung and exotic places like Rotorua in New Zealand. But Babcia was no woman of the world! Indeed, the photos tell of a woman who loved the simple and nearer things of life – family, flowers, and friends with whom she would gossip and laugh for hours so very excitedly (and loudly) on the phone, or over a seemingly-bottomless banquet of ham, gurki, cottage cheese and semi-stale rye bread, not to mention the kapusniak or borsch swimming in sour cream, and the pierogi, golabki, and babka. So deceived was she by the seduction of food that she seemed to believe that if the item bore the label ‘Weighwatchers’ it meant that you could actually eat three times as much and still lose weight. Those new to the Goroncy dining experience learnt quickly not to pile their plates too early in the drama, for it would not be long before they heard the words from one who grazed more than feasted, and from whose mouth would come the command, ‘Take more, you too skinny. Look – ham, potatoes … you want something else?’. Convinced by the conspiracy that ‘restaurants make you stomach poison’, Babcia was devoted to home cooking. But it was a passion not primarily birthed by a paranoia of restaurants, or by economic rationalism, though, no doubt, the latter was a factor for a generation formed in a landscape where scarcity was the norm. Her passion for cooking, rather, was birthed by the fact that this was a primary and joyful means by which she could serve her friends and family. Indeed, one could turn up at all hours of the night – and I frequently did – and she would jump out of bed and spring into action – ‘you want something to eat Jay’ – so concerned as she was that I was fading away. Indeed, she was nothing if not hospitable to people – whether to those known to her, or to strangers.

The photos also bear witness to her love of gardening, and particularly to her flowers; her love for shopping – the perpetual hunt for a bargain, a trait that her eldest son has inherited; her devotion to her favourite TV programs, among which was ‘The Young and Wrestles’; and, in more recent years, the fascinating friendship that she enjoyed with Bobby, the only dog I’ve ever met who has become increasingly-less housetrained over the years, reverting, it would seem, to something like the life he had before he was rescued by the RSPCA, and before he met Babcia. And that reminds me of a story. I remember when Judy and I bought Bobby as a gift for Babcia. She was so adamant that she didn’t want a dog and that we should take him back to North Melbourne straight away. But we were stubborn too – hey, it’s in the blood! – and eventually, we convinced her to keep Bobby on a two-week trial. If, after that time she still felt the same, we’d take him away. Within a week, we asked her how she was doing with Bobby and whether she wanted us to take him back. And she said, ‘I not give you for thousand dollar!’ And so their friendship began. It was really special, and actually quite funny at times, to see how she and Unc and Bobby related, and how quickly Bobby learnt to understand Polish.

And there are things that the photos tell less about, if at all. They tell little of the way in which Babcia was a model of multicultural hospitality and friendship, happy as she was to share her life with her Macedonian and Italian and Chinese neighbours. They don’t tell of the time that she bowled up to Highpoint to see a movie on her own for the first time in her life – it was the Jesus film. Nor of the time that two of us took her to see Shakespeare in Love – an experience much more interesting, it must be said, than the movie was.

By far the most common subject in her albums, however, were her children, and their children, and their children. She loved us. And as much as her heart broke for each of us when things were going haywire, she rejoiced to hear every bit of news of our comings and goings, especially, I think, of us grandchildren, seeing in us, perhaps, a way of healing for fractures that had opened up in our family.

Much like she welcomed Unc, Babcia also welcomed a frightened teenaged-version of me into her home and daily life, and she was for me a safe and stable lifeboat around which I learnt to find my feet again. And so she was for many years thereafter – a fun and caring person to be around, even if sometimes very impatient, and one with whom I could truly be myself. I felt safe with her, even when she would harp on about things that I thought were significantly less than vital. And no matter how critical she might have been at times towards others – and, yes, she did, it must be said, possess quite a judgemental streak – to those foibles of her own family she was almost blind – or at least she tried to be so. And her unflinching and stubborn blindness extended also to herself. So, for example, this one who claimed to be a ‘very good driver … never make me accident’, did not think twice about going anti-clockwise around a busy car park roundabout in order to secure a spot closer to her shop of choice.

One of the great things that that great Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky has taught me is that earthly life cannot flourish without the conviction that the narratives of growth and conflict and attention that characterise our life here are not fated to come to an end. But this is not to say that some things will not come to an end. With the writer of the final book of the Bible, Dostoevsky too believed in the coming of the day of shalom. The day of shalom, the day of peace, will not be characterised by a peace with death. With death, there can be no such peace. Rather the day of shalom means a time when there will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things will have passed away. Though I am uncertain of the precise form that such an event will take, my faith in one for whom death is neither foreign nor the end of all things gives me reason to look forward to meeting Babcia again, to believing that life triumphs even over death. But until then, do widzenia Bubcia, do widzenia.

A Prayer

When the signs of age begin to mark my body,

and still more when they touch my mind;

when the ill that is to diminish me or

carry me off strikes from without

or is born within me;

When the painful moment comes in which I suddenly

awaken to the fact that I am ill or growing old;

when I realise that I must soon relinquish all whom

I hold dear and all in life that I have loved;

and above all at that last moment when I feel

I am losing hold of myself and am absolutely

passive within the hands of the great unknown

forces that have formed me;

In all those dark moments, O God, grant

that I may understand that it is you

who are painfully parting the fibres

of my being in order to penetrate

to the very marrow of my substance

and bear me away within yourself.

Amen.