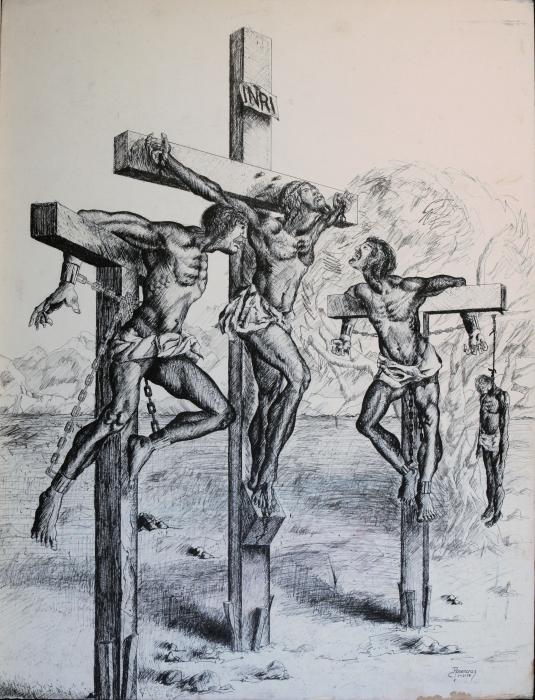

Jesus said to him, ‘Friend, do what you are here to do’. (Matthew 26.50)

In the darkness of Gethsemane, amid the clash of swords and the flicker of torches, Jesus addresses his betrayer with a word that stops us in our tracks: hetairos (‘friend’). This Greek word is not the warm philos of intimate companionship, but neither is it a term of contempt. It carries the weight of association, of one who has walked alongside, shared meals, witnessed miracles. And Jesus uses it at the precise moment when that companionship is being weaponised against him.

The theological scandal of this address lies in its refusal to unmake the relationship at the very moment it is being violated. Judas arrives with a kiss – the gesture of greeting now twisted into a signal of betrayal, of identification for arrest. Yet Jesus does not revoke the covenant of their shared journey. He names Judas as what he has been and will be, even as Judas enacts what he has chosen to become.

This moment in the garden confirms what was already enacted hours earlier in an upper room. The church’s liturgy captures this with haunting precision: ‘On the night he was betrayed, [Jesus] took bread …’. Not the night before. Not the night after Judas left. The very night of betrayal itself. And the bread broken and shared was given to the twelve, not to eleven. There’s all the hope of the world in that.

The ‘friend’ spoken in Gethsemane thus echoes the broken bread given in the upper room. Both gestures refuse to allow betrayal to have the final word on the relationship. Both offer dignity and recognition at the precise moment when they are least deserved and will be most thoroughly rejected. Knowing does not prevent giving.

This, it seems to me, has profound implications for how the Christian story invites us to understand and embody our own relationships. Jesus’ calling Judas ‘friend’ does not prevent consequences – Judas’ story ends in disaster, just like Jesus’, at least penultimately. Yet it also suggests something subterranean that cannot finally be completely broken. When I think about my own damaged relationships, this is where both hope and pain get generated.

Those who recognise in Jesus something of the divine life see in that meal and garden something of the relentless and outlandish logic of grace, of a love that precedes our choices and persists through our blunders. The bread given to Judas is the same bread given to Peter, who will deny, and to all the other disciples, who will scatter.

For those of us who live in the aftermath of our own experiences of betrayal, small and large, this gives pause. Maybe the same voice that called Judas ‘friend’ in the garden still calls us by name, places bread into our uncertain hands, and refuses to let the worst moments define the terms of our relationships? This, we hope, is the character of divine love: unconditioned not because it is indifferent to betrayal, but because it remains loyal even when loyalty is not returned.