Richard Flanagan writes:

So this is what we have come to as a nation.

The wretched of the earth, because they were no longer safe where they lived, sought to come here. With a determined cruelty, we kidnapped and imprisoned them in Pacific lagers. These lagers became synonymous with the idea of hellholes because it was important to our government that they be – and be known as – hellholes.

On this policy of deterrence, as it was called, which had as its declared purpose to make innocent human beings suffer indefinitely, we spent billions of dollars. To this end we had truck with vile regimes such as Sri Lanka’s. And to this end we began forsaking our democratic rights.

In the camps the refugees were made to answer to numbers given to them as their new identity. Denied their names they were not even allowed their stories. Every attempt that could be made was made by the Australian government, from the petty to the disturbing, to deny journalists access to the Pacific lager. When it came to imprisoned refugees free speech became a crime: for some years any doctor, nurse or social worker in the camps who publicly reported on the many instances, now well-documented, of rape, murder, suicide and sexual abuse of refugees was liable to two years’ imprisonment.

And why?

Because evil was being done to the innocent, and to that truth there is finally no justification that even the most powerful could make. And so it mattered that Australians not know of the mounting crimes for which all Australians will be finally accountable.

All this too was done in our name by our governments, of both left and right. And, more or less, if we didn’t tacitly agree, few of us disagreed enough. And perhaps we didn’t really want to know.

Once we Australians had led the world in democratic reform. Once it seemed possible that we might overcome the violence of our wars of invasion and reconcile with our Indigenous brothers and sisters. Once it seemed that we might make of ourselves a beacon for freedom and tolerance, a country of many peoples that welcomed the newly dispossessed as we had in turn once been welcomed. We were a nation born out of the evils of invasion and convictism. It was not that we saw ourselves as infinitely perfectible. It was rather that we were aware of what the alternatives were.

Now we are seen globally as the inventors of a particularly vile form of 21st century repression, in which the innocent are subjected to suffering in a prison where the crime is never named, no sentence is ever passed, and punishment is assured. For this achievement Australia now enjoys the praise of European neo-fascists and American white supremacists.

Some praise. Some achievement.

It is hard to say what is most horrifying in this long saga but the intent of the Australian government to now abandon the refugees it kidnapped, scattering them across an impoverished and corrupt country with a notorious reputation for violence, is an affront to any notions of humanity or decency.

When, out of fear for what might befall them should they leave, some hundreds of refugees refused to move from the Manus compound, there began a protest in which the refugees used the only thing left to them: their bodies.

Over the years we had taken away their rights, their future, even their hope. Three weeks ago we cut off their water, food and medical supplies. Risking starvation, dysentery, cholera and violence, some hundreds of refugees asserted with their flesh the one thing which Australia could not steal: their human dignity.

On Wednesday the UNHCR described what was now unfolding on Manus as a humanitarian crisis that was entirely preventable and a “damning indictment of a policy meant to avoid Australia’s international obligations”.

On Thursday 12 Australians of the Year signed an open letter calling on the government to restore water, food supplies, electricity and medical services to the refugees, warning it was a “human disaster that was unfolding” and that “it was inevitable that people will become sick and die”.

Instead of this moderate course of action, on the same day police in Papua New Guinea began clearing the Manus compound. According to witnesses, refugees were beaten with sticks to forcibly relocate the remaining hundreds of protesting men. This violence against the most powerless and weak was supported and promoted by the Australian government, as it has previously supported and sanctioned the poisoning of the refugees’ water collected in from sumps and rainwater, the destruction of the few pieces of property they possess, and the destruction of their scant remaining food and medicine supplies.

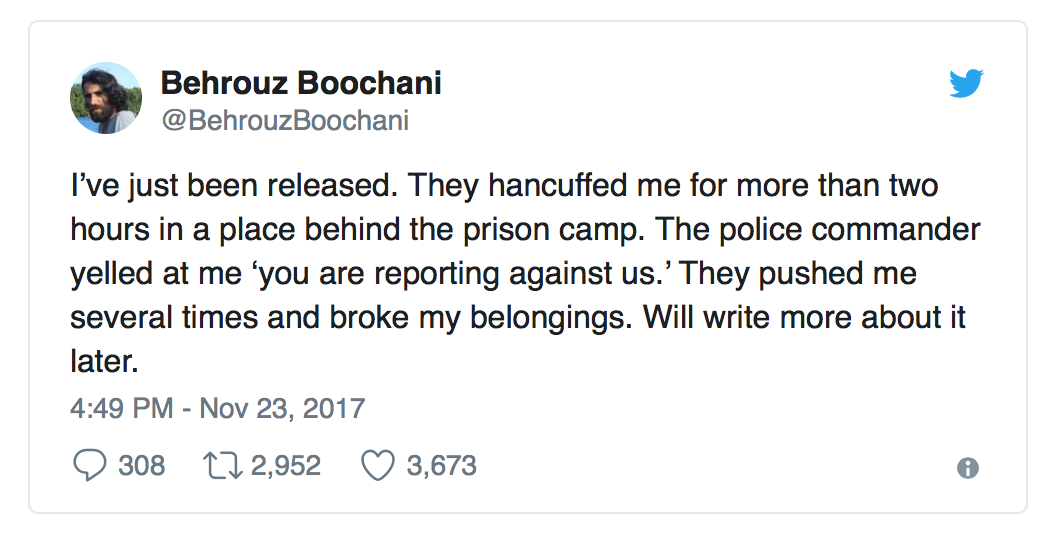

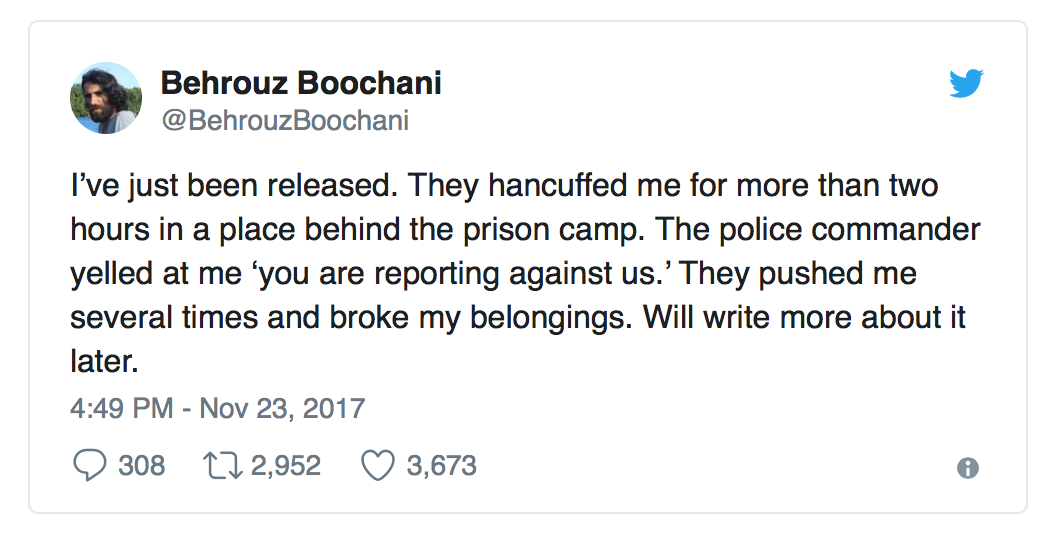

And then there came the news the Iranian journalist and refugee Behrouz Boochani had been taken away by PNG’s much-feared mobile squad, a notorious paramilitary police unit which, according to a report in the Age in 2013, is “allegedly responsible for rapes, murders and other serious human rights abuses” and funded by Australia’s immigration department “to secure the Manus Island detention centre”.

Behrouz Boochani was targeted for one reason and one reason only: he has been the voice of truth speaking from the appalling reality of the Pacific lagers.

It is difficult to believe that all this is not being masterminded – if the word is not too grand for such thuggery – at the highest levels of the Australian government.

Released some hours later, Boochani tweeted that he had been left handcuffed for two hours while he was “pushed several times”, had his belongings destroyed by the police, and was yelled at by the police commander that he “was reporting against us”. Boochani knows now, more than ever, that he is a marked man.

And in these circumstances he has, in characteristic fashion, continued to report.

His courage over the four years of his internment in the face of the horror of Manus – a hell of repression, cruelty, and violence – has been of the highest order. Behrouz Boochani kept on smuggling out his messages of despair in the hope we would listen.

It’s time we did.

All states commit criminal and sometimes wicked acts. The necessary mark of a democracy is the freedom to tell the truth about these crimes so that they can be ended and the guilty punished.

To be a writer is not to simply believe in freedom but to practise it every day with your words. Each word allows us to find ourselves in others, and in others to know we are not alone.

In the vacuum of reportage that the Australian government created one man kept getting the truth out. Behrouz Boochani’s words found me as they found so many others.

Now I hope mine find him.

We choose whether we live or whether we wait for death. Through his words Behrouz chose to live. His words showed that while our government had jailed his body, his soul remained that of a free man.

I am not sure if I would have had his courage were I to find myself in his situation. Perhaps that is why I admire it deeply.

Behrouz Boochani reminded Australia of what it had become. We should thank him and honour him for his warnings of what was happening to our country. Instead we enabled his imprisonment, and who can say what this marked man’s fate may yet be?

His detainment yesterday highlights the moral bankruptcy of the Pacific solution, its essentially criminal nature, and the growing dangers it presents to our democracy.

The shame of this time will outlive us all. Our children and grandchildren will have to remake the broken trusts, the sacred freedoms, the necessary liberties, that we traded away in our ignorance and our gullible fear. They must rekindle as necessary national virtues kindness and compassion to the weakest.

But we must begin the work now, with urgency, with determination, of rebuilding our nation’s honour, and our collective dignity. Because if we don’t, if we think it doesn’t affect us, the alternative is that what is happening on Manus will begin to happen here.

At the time of writing, Manus remains in crisis, with 300 refugees still in the compound. Who knows what fresh onslaught of violence is awaiting them? While outside wait the paramilitary thugs, inside the refugees search in the darkness for drinkable water, they scrounge for what little food was not destroyed, these 300 men who now face the determination of our government that they vanish from the face of the earth, and with them their terrible story that shames us all.

But that story demands investigation, not obliteration.

There must be a royal commission into the Pacific camps, the grotesque amounts of money wasted on them, the lies, the deceit and undemocratic practices used to ensure their ongoing existence, to determine the extent of Australian involvement in the PNG police’s latest acts, and to ascertain and if necessary prosecute those responsible for the many well-documented cases of the abuses of human rights on both Manus and Nauru.

If we can muster no feeling for the starving, sick and thirsty refugees waiting in the ruins of their prison for the next attack, spare a thought for what our future might look like if Peter Dutton begins persecuting journalists here with his newly acquired secret police powers. We should not forget the plans in 2015 for Dutton’s newly militarised Border Force officials to patrol Melbourne streets checking people’s papers, abandoned only in the face of overwhelming public anger.

Behrouz Boochani may be the first journalist to be detained for revealing the evil of our Pacific gulags. But how can we be confident he will be the last, and who knows what new government folly will need a repressive cloak of secrecy to safeguard its many failings?

In Boochani’s writings is a spirit Australia has lost: brave, honest, generous and free. Once he wanted to come here. Now we need him and all that he stands for more than ever.

And if, in these next few days any harm should come to Behrouz Boochani, for whose safety many now fear, the responsibility for that crime will not fall to PNG government or its police. It will be Peter Dutton’s.

[Reprinted with permission from The Guardian]

[Image: Reuters]

Every now and then – and more ‘then’ than ‘now’ – public discourse concerns itself with the question of class. (This happened briefly, for example, after the recent, although it doesn’t feel that way, presidential elections in the USA. At the time, some good commentary appeared in the US, and some people even wondered for a moment if Bernie wasn’t as mad as previously thought.)

Every now and then – and more ‘then’ than ‘now’ – public discourse concerns itself with the question of class. (This happened briefly, for example, after the recent, although it doesn’t feel that way, presidential elections in the USA. At the time, some good commentary appeared in the US, and some people even wondered for a moment if Bernie wasn’t as mad as previously thought.)