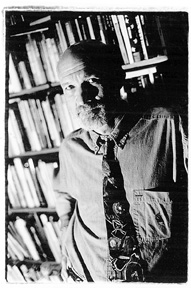

I have posted on Alfonse Borysewicz before: here and here. In the latter post I mentioned that Alfonse would be delivering the Brooklyn Oratory‘2009 Baronius Lecture. He has been kind enough to send me a copy:

I have posted on Alfonse Borysewicz before: here and here. In the latter post I mentioned that Alfonse would be delivering the Brooklyn Oratory‘2009 Baronius Lecture. He has been kind enough to send me a copy:

Baronius Lecture 2009 – Alfonse Borysewicz

Oratory Church of St. Boniface, Brooklyn, New York

Can You Be a Contemporary Artist and a Practicing Catholic?

There is a story about a rabbi going to see another rabbi and finds himself immersed in the reading of the Torah. “What are you doing?”-“I’m trying to interpret a passage that I’ve been studying for years and can’t explain completely to myself.” “Let me see: I’ll try to explain it to you myself.” “That won’t do any good, I can explain it to other people; what I can’t do is explain it to myself.”

In 1977, on my first day of seminary, after two years of college at a Jesuit university in Detroit, I found in my hands a book of poems by Gerard Manly Hopkins. To this day I still make pilgrimages with that old college Penquin paperback; particularly one poem, “Carrion Comfort,” which has become a personal mantra for me. The opening lines of this heart-felt poem are:

NOT, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee;

Not untwist-slack they may be-these last strands of man

In me ór, most weary, cry I can no more….

Three decades have passed since I finished my seminary studies, and, in a clumsy way, decided not to become a priest, and instead have spent now 30 odd years working as a painter, first in Boston, with quick recognition and subsequently in the New York art world. Today when I ask myself if I can be a contemporary artist and a practicing Catholic, Hopkins’ words, “despair” , “weary” and “these last strands of man,” squeeze me hard. For me this question is a real-life drama. And it is not as simple as one might think.

In his autobiography, Henry Adams, heir to two presidents and an accomplished author of biographies, novels, a nine-volume history of the US, and works on education and art, portrays himself as a misfit. From a literary standpoint his life was an extraordinary success, but in his own estimation he had failed miserably. He saw himself as a human fossil, a survivor from an earlier era confronted with a bewildering, changing world. In The Education of Henry Adams, he wrote: “What could become of such a child of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when he should wake up to find himself required to play the game of the twentieth?”

Like Adams, I’m often tempted to see myself as a human fossil. As a practicing Catholic I am in many ways a product of other centuries, yet contemporary art requires me to play-exclusively- the game of the twenty-first century, a world that changes even faster than the one Adams lived in. With the compounded temptation to idolize an ever increasing material and technological world at the expense of a sacramental vision of the world.

Like Adams, I’m often tempted to see myself as a human fossil. As a practicing Catholic I am in many ways a product of other centuries, yet contemporary art requires me to play-exclusively- the game of the twenty-first century, a world that changes even faster than the one Adams lived in. With the compounded temptation to idolize an ever increasing material and technological world at the expense of a sacramental vision of the world.

In the book The Church Confronts Modernity, published by Catholic University, several authors reflect on the church and culture in Quebec, Ireland, and the United States. With regard to the “home country,” so to speak, one author makes a distinction between two Catholicisms in America: one emphasizing authority, one emphasizing individual conscience. The former highlights knowing the church’s teachings; the other, being a good Christian. The first views modern society as evil, the second as God’s creation. And so it goes.

Regardless of which model you follow, the dilemma is the same: either you can risk denying your ultimate identity by changing (or pandering), or else by refusing to change you can become obsolete, out of step with the modern, or should I say, the lost modern world.

When I was in my thirties, my paintings, though they were full of religious meaning for me, were safely abstract, and I was welcomed into the gallery scene of the time. As I entered my forties, my Catholicism became more important to me (the culture wars, raising children, terror and war, etc.), and my paintings began to change (less abstract, more representational with direct religious imagery). This new work was no longer welcome in the galleries that had once shown my work and, it seems, in the dialogue of the culture. Recently I have come to the realization that my erasure from the art world was no fluke. Rather my initial 15 years of success was the fluke. That is to say, my intuitive drive to unite my art with my faith and religion was doomed to fail in the culture world at large from the get go. The boulder I have been pressing to move, the truncated and distorted views of God and the Faith and the Church, has been there for centuries. And it’s taken me 51 years to realize this. But the wonder and gift is I have realized this. The question now is do I attempt to participate in the contemporary culture-art world by changing and updating or as Zsigmond Moricz wrote in the great Central European classic novel of a budding artist’s struggle, do I remain “faithful unto death”?

Why remain faithful to religious imagery in an increasing secularized world? This is a question I often ask myself at around five AM when I wait for the sunrise and the soon honking horns outside my window. Why am I still pressing this boulder that has cost my family and I so dearly? It is an old question, and one that lives at the heart of Christian worship, which brings ancient events into the here and now by presenting us with images. Our liturgy, so beautifully celebrated in this Church, celebrates events that take place in the present, and are at the same time linked to a historical past we can barely imagine. Yet this is what both the Middle Ages and the Renaissance did: they portrayed biblical stories in a contemporary setting.

I can think of many more recent artists who do this, but one American nomadic modernist in particular comes to mind: Marsden Harltey of New York and Maine, who in 1941 painted Fisherman’s Last Supper, an ordinary family at dinner minus the loved ones lost recently at sea. From this fishing village portrait to the Ghent Altarpiece or The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, all imply, as Heather Dubrow writes in The Challenge of Orpheus, that “the figure within it is, as it were, alive and well in that very church at that very moment.” Saint Augustine echoes this: “Easter happened once yet the yearly remembrance brings before our eyes, in a way, what once happened long ago.” Why this recreation of Christian events, reoccurring from medieval peasants to the geniuses of the Renaissance to New York neurotics like Marsden Harltey and myself? Augustine answers: “for fear we should forget what occurred but once, it is re-enacted every year for us to remember.”

One cannot talk about American Catholic identity, culture, and the artistic endeavor, without (forgive me) genuflecting to the writer working from Milledgeville, Georgia-Flannery O’Connor. Echoing Chesterton, O’Connor insisted that the free will essential to Catholicism also freed the imagination. As she put it: “The Catholic novelist believes that you destroy your freedom by sin; the modern reader believes, I think, that you gain in that way.” In other words, do you live and create in an ordered autonomy where your freedom is guided by transcendent values or a radical autonomy where anything goes. Or, in short, a freedom that views life as a gift or a freedom that views life as something to me manipulated. I think the latter is the prevalent operative mode in our culture today, though recently it is showing signs of stress. As Karl Barth writes even God put limits on God’s own freedom by resting on the seventh day of creation.

So where am I? Like Adams, am I a misfit? With my sacred obsessions, I feel like a genetic mutant unfossilized from the thirteenth century into the twenty-first. When asked why she had a penchant for writing about freaks, Flannery O’Connor replied, “because I can still recognize one.” Why, in a culture divorced from and hostile to religious devotion, am I painting religious images and icons? Because, as O’Connor said, “I can still recognize one.”

The Czech philosopher Habermas warns us that “global capitalism’s triumphal march encounters few genuine oppositions and, in that regard, religion, as a repository of transcendence, has an important role to play. It offers a much-needed dimension of otherness: the values of love, community, and godliness to help offset the global dominance of competitiveness, acquisitiveness, and manipulation that predominates in the vocational sphere.” Or more basic, I don’t want my children or their children, my friends and their friends, or the passerby/stranger to abandon or forget their place in, as Pope Benedict illuminated in his first encyclical Deus Caritas Est, in this ongoing love story. To bring it back home from a hymn sang here two just two Fridays ago at the noon mass (#630 Lord, Whom Love is Humble Service):

Still your children wander homeless

Still the hungry cry for bread

Still the captives long for freedom

Still in grief we mourn our dead

As. O Lord, your deep compassion

Healed the sick, and feed the soul.

Use the love your Spirit kindles

Still to save and make us whole.

Look around, folks. You might not see anything like this for some time to come. Honestly, I have nowhere to go with these works. The galleries won’t exhibit them; they’ve abandoned religious expression. Except for occasional moments like this, the Church and its parishes won’t display them. They have neglected or forgotten their own heritage, and so my work seems unusual to them at best, or at worst, dangerous. The universities, well, they will only show them on PowerPoint. ..Or perhaps Saul Bellow was right when he said “art can’t carry the weight of religion.”

My hero, the Jesuit theologian Bernard Lonergan, saw the crisis of culture and faith years ago. In 1967, he wrote: “There is bound to be formed a solid right that is determined to live in a world that no longer exists. There is bound to be formed a scattered left, captivated by now this and that new possibility. But what will count is a perhaps not a numerous center, big enough to be at home in both the old and new, painstaking enough to work out one by one the transition to be made, strong enough to refuse half measure and insist on complete solutions even though it has to wait….”

My hero, the Jesuit theologian Bernard Lonergan, saw the crisis of culture and faith years ago. In 1967, he wrote: “There is bound to be formed a solid right that is determined to live in a world that no longer exists. There is bound to be formed a scattered left, captivated by now this and that new possibility. But what will count is a perhaps not a numerous center, big enough to be at home in both the old and new, painstaking enough to work out one by one the transition to be made, strong enough to refuse half measure and insist on complete solutions even though it has to wait….”

In 1987, desperately hungry for a community to worship with, I took a bike ride to the Cathedral of St. James and found my home. After that first mass and walking up to Fr. Jim Hinchey inquiring about Baptism for my daughter in budding he soon put me to work in the bookstore. Then the transition from St. James to here when Fr. Dennis Corrado implored me to make a processional cross, do some gold leafing, and more…I will never forget his mandate: “Alfonse don’t worry about money because we don’t have any.” Though profoundly grateful to have worked in this church, to bring my art in this sacred space, I don’t think I can stomach again, like I did a few weeks ago and again ten years before, right here, holding the ladder while Fr. Mark Lane balances himself like an acrobat on these ladders to reach a hook, without a nerve in his body trembling while I shook below.

As for myself, like Saint Augustine, I have become a question to myself. About a year ago the Jesuit magazine printed an article about my works entitled “An Ordinary Mystic”. I actually brought up the Rahnerian idea after hearing about it from a friend; a beautiful idea. As my friend

Jesuit Michael Paul Gallagher writes “ future believers will have to be mystics or else they will not have faith. Clearly this cannot mean that everyone has to have the special gift of mystical saints. Rather it suggests that, in a more secular context, faith will have to be grounded in a personal experience of grace. It will need an ability to recognize the Spirit at work in one’s ordinary life.”

On the question of whether one can be a Catholic artist and be a contemporary painter, I will defer. I’m too saturated, too involved, too subjective, too neurotic to answer. They say that one doesn’t look at icons, but they look at you. My paintings, my icons, are looking down at you. Let me know. There-on my left-is Mary Magdalene. The Danish philosopher Kierkegaard writes “the words of the angel to Mary Magdalene at the grave could be used here: Do not be afraid; for I know that you seek Jesus of Nazareth; because until confidence appears, the person who seeks Jesus at first actually experiences fear before him, before his holiness.” Or as the filmmaker Bresson in Diary of a Country Priest, echoing St. Therese of Lisieux , all is grace.

Yesterday’s New Statesman includes a piece by

Yesterday’s New Statesman includes a piece by