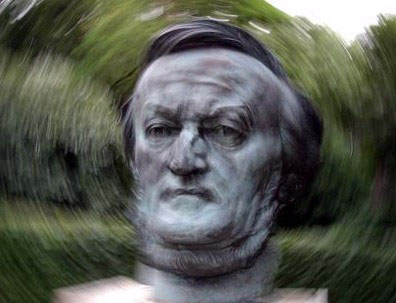

David P. Goldman has posted a fascinating reflection on Why We Can’t Hear Wagner’s Music. The entire piece is well worth the time it takes to read it, but here’s a few snippets:

David P. Goldman has posted a fascinating reflection on Why We Can’t Hear Wagner’s Music. The entire piece is well worth the time it takes to read it, but here’s a few snippets:

‘Why did Wagner loom so large to his contemporaries? The answer is that he evoked, in the sensuous, intimate realm of musical experience, an apocalyptic vision of the Old World. Wagner’s stage works declared that the time of the Old Regime was over—the world of covenants and customs had come to an end, and nothing could or should restrain the impassioned impulse of the empowered individual. Wagner’s baton split the sea of European culture.

It is hard to make sense of what has become of the West without engaging Wagner on his chosen terrain in the musical theater, for electronic media are a poor substitute for live performance. To engage Wagner on that chosen terrain is harder to do as directors bury him under supposedly creative interpretations. We have had Marxist, feminist, and minimalist versions of The Nibelung’s Ring and a production of Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal, dominated by a video image of a decomposing rabbit. A demythologized Wagner opera, much less a decomposing one, is not Wagner at all; as Thomas Mann said, Wagner’s work “is the naturalism of the nineteenth century sanctified through myth.” Without the myth, there is no sanctification, and Wagner’s effort to substitute art for religion becomes incomprehensible …

Wagner’s power comes, first of all, from his music, but we have lost the capacity to hear it the way Baudelaire and Mahler did. And our inability to hear Wagner’s music constitutes a lacuna in our understanding of the spiritual condition of the West. Despite Wagner’s reputation for compositional complexity, his musical tricks can be made transparent to anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of music. In some ways, Wagner is simpler to analyze than the great classical composers. Because—as Nietzsche said—Wagner is a miniaturist who sets out to intensify the musical moment, his spells, at close inspection, can be isolated …

Wagner set out to destroy musical teleology, which he abhorred as the “tyranny of form.” As Nietzsche perceptively noted:

If we wish to admire him, we should observe him at work here: how he separates and distinguishes, how he arrives at small unities, and how he galvanizes them, accentuates them, and brings them into pre-eminence. But in this way he exhausts his strength; the rest is worthless. How paltry, awkward, and amateurish is his manner of “developing,” his attempt at combining incompatible parts.

That is what Rossini meant when he said that Wagner has beautiful moments and awful quarter-hours. (He also said that Lohengrin couldn’t be appreciated at first hearing, and that he had no intention of hearing it a second time.) Wagner had a gift, as well as an ideological purpose, for the intensification of the moment. If Goethe’s Faust bets the Devil that he can resist the impulse to hold onto the passing moment, Wagner dives headfirst into its black well. And if Faust argues that life itself depends on transcending the moment, Wagner’s sensuous embrace of the musical moment conjures a dramatic trajectory toward death …

That is what Rossini meant when he said that Wagner has beautiful moments and awful quarter-hours. (He also said that Lohengrin couldn’t be appreciated at first hearing, and that he had no intention of hearing it a second time.) Wagner had a gift, as well as an ideological purpose, for the intensification of the moment. If Goethe’s Faust bets the Devil that he can resist the impulse to hold onto the passing moment, Wagner dives headfirst into its black well. And if Faust argues that life itself depends on transcending the moment, Wagner’s sensuous embrace of the musical moment conjures a dramatic trajectory toward death …

If Wagner himself was not quite a premature Nazi, he remains a horrible affirmation of Franz Rosenzweig’s claim that Christianity, once severed from its Jewish roots, would revert rapidly to paganism …

Wagner’s shift away from goal-oriented motion to intensification of the moment deafens our ears to the expectations embedded in classical composition and ultimately ruins our ability to hear his manipulation of these expectations. In other words, Wagner’s aesthetic purpose is at war with his methods. Once we are conditioned to hear music as a succession of moments rather than as a journey to a goal, we lose the capacity for retrospective reinterpretation, for such reinterpretation presumes a set of expectations conditioned by classical form in the first place. Despite his dependence on classical methods, Wagner’s new temporal aesthetic weakened the capacity of later musical audiences to hear classical music. As Sir Thomas Beecham joked, people really don’t like music; they just like the way it sounds …

What made Wagner his century’s most influential artist was not merely that he portrayed as inevitable and even desirable the fall of the old order but that through his music he turned the plunge into the abyss into an intimate, existential experience—a moment of unbounded bliss, a redemptive sacrifice that restores meaning to the alienated lives of the orphans of traditional society. On the ruins of the old religion of throne and altar he built a new religion of impulse: Brünnhilde becomes Siegfried’s co-redemptrix in Wagner’s heretical Christianity.

And that is why (as Bernard Shaw said) Wagner’s music is better than it sounds. There really are a few moments worth the painful wait, when Wagner’s application of classical technique yields the illusion of timelessness. Because we are mortal (as I argued in “Sacred Music, Sacred Time”), and our time on earth is limited, a transformation of our perception of the nature of time bears directly on our deepest emotions—those associated with the inevitability of our death. That, I think, is what Schopenhauer tried to get at when he argued that “music does not express this or that particular and definite pleasure, this or that affliction, pain, horror, sorrow, gaiety, merriment, or peace of mind, but joy, pain, horror, sorrow, gaiety, merriment, peace of mind themselves, to a certain extent in the abstract, their essential nature, without any accessories, and so also without the motives for them.”’

Read the whole essay here.

Thanks! I am a huge fan of Wagner.

LikeLike

I sometimes wonder if Wagner wouldn’t have been a better symphonic composer than an opera composer: his musical interludes are just superb. I first came across them when television presented Georg Solti conducting them. They were mind-blowing. But I also sat through (all? most of?) either Lohengrin/Parisfal and went to sleep several times.

LikeLike

Tell me Mike: When you sat through Lohengrin, was it ‘live’ or on TV? It makes a huge difference. I fall asleep watching almost anything on TV.

LikeLike

Congratulations,

Well, perhaps all too well, crafted article.

LikeLike