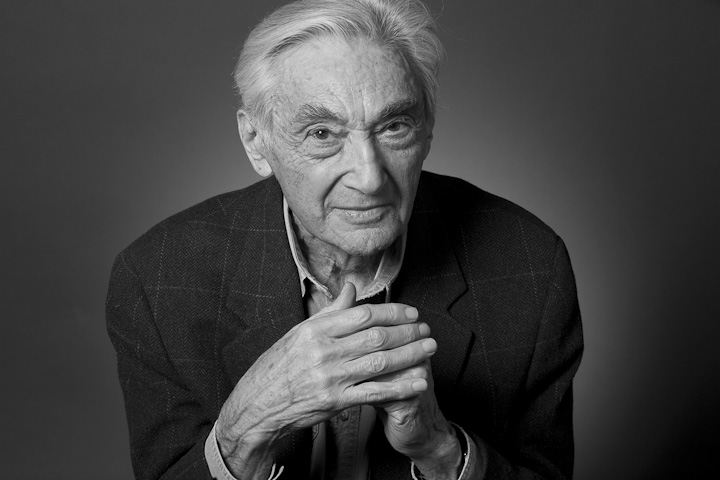

Saddened to read today of the death of Howard Zinn, author of A People’s History of the United States: 1492 to Present, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times, Howard Zinn on Democratic Education, Passionate Declarations: Essays on War and Justice, The Politics of History, Marx in Soho: A Play on History, Emma, A Power Governments Cannot Suppress and a host of other books. James Carroll’s assessment of this ex-air force bombardier is spot on, that ‘Howard had a genius for the shape of public morality and for articulating the great alternative vision of peace as more than a dream’. Typically provocative, and always timely, I don’t always agree with Zinn, but I’ve appreciated everything I’d read from his engaging pen and the gentle courage with which he said it.

For those unfamiliar with Zinn’s thought, here are a few tasters:

‘It is interesting that God is brought into the picture when the government is doing great violence. Maybe it’s when you are doing great violence that you desperately need some support. You’re not going to get any moral support from any thinking person, but since God isn’t thinking at the moment, maybe you can pull out God to support you’. – Howard Zinn, Terrorism and War (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2002), 94.

‘History is always a good entity to call upon if you are hesitant to call upon God because they both play the same role. They are both abstractions; they are both actually meaningless until you invest them with meaning. I’ve noticed that President Bush calls upon God a lot. I think he’s hesitant to call upon history because I think the word history throws him; he’s not quite sure what to do with it, but he’s more familiar with God. History is invoked because nobody can say what history really has ordained for you, just as nobody can say what God has ordained for you. It’s an empty vessel, which you can fill in whatever way you can. So you can say that history has decided that the United States will be the great leader of the world and that American values, values being another empty vessel that you can fill with anything you want, will be transmitted to the rest of the world. So you can fill history, that abstraction history, with anything you want, use it whenever you want. Political leaders, I guess, suppose that the population is as mystified by the word history as they are by the word God, and that therefore they will accept whatever interpretation of history is given to them. So the political leaders feel free to declare that history is on their side, and the way is open for them to use it in whatever manner they want’. Howard Zinn and David Barsamian, Original Zinn: Conversations on History and Politics (Pymble: HarperCollins, 2006), 131–2.

‘To me, a democratic education means many things: It means what you learn in the classroom; it means what you learn outside the classroom; it means not only the content of what you learn, but it means the atmosphere in which you learn it; it refers to the relationship between teacher and student. All of these elements of education can be democratic or undemocratic.

And so for the content of education to be democratic, it must take its cue from the idea of democracy, the idea that people will determine their own destiny. And therefore, it means students have a part in this. Students as human beings, as citizens in a democracy, have the right to determine their lives, have a right to play a role in the society. And therefore, a democratic education gives students the kind of information that will enable them to have a power of their own in the society.

And what that means is really to give the students a kind of education that, going into history, suggests to the students that historically there have been many, many ways in which ordinary people – people as ordinary as the student feels as he or she is sitting in the classroom – can play a part in the making of history, in the development of their society. So that a democratic education in that sense is an education that gives the student examples in history of where ordinary people have shown their power and their energy in not only reshaping their own lives but playing a part in how society works. That would be the substance of a democratic education, or part of the substance of a democratic education.

And then the relationship of the student to the teacher. There is democracy in the classroom. The understanding given to the student that the student has a right to challenge the teacher, that the student has a right to express ideas of his or her own. That education is an interchange between the experiences of the teacher, which may be far greater than the student in certain ways, and the experiences of the student, which are unique, since every student has a unique life experience, one which a teacher has not had, and therefore the student is in a position to throw into the educational reservoir of the class the student’s own experience. So the interchange between student and teacher, the free inquiry that is promulgated in the classroom, a spirit of equality in the classroom, to me that is part of a democratic education’. – Howard Zinn and David Barsamian, Original Zinn: Conversations on History and Politics (Pymble: HarperCollins, 2006), 132–3.

‘Patriotism is being used today the way patriotism has always been used, and that is to try to encircle everybody in the nation into a common cause, the cause being the support of war and the advance of national power. Patriotism is used to create the illusion of a common interest that everybody in the country has. I just mentioned the necessity to see society in class terms, to realize that we do not have a common interest in our society, that people have different interests. What patriotism does is to pretend to a common interest. And the flag is the symbol of that common interest. So patriotism plays the same role that certain phrases in our national language play, and that is to create the illusion of common interest. The words that are used are national security, pretending that there is only one security for everybody, one kind of security for everybody; national interest, pretending that there is one interest for everybody; national defense, pretending that the word defense applies equally to all of us. So patriotism is a way of mobilizing people for causes that may not be in the people’s interest’. Howard Zinn and David Barsamian, Original Zinn: Conversations on History and Politics (Pymble: HarperCollins, 2006), 148–9.

Great posting–well done.

LikeLike

I’ve read a lot of Zinn and was lucky enough to meet him a couple times. He did not disappoint and was truly a mensch.

LikeLike