Commenting on Job’s three theological friends, Slavoj Žižek contends that ‘God is the only true materialist … [God] comes and says there is no transcendent meaning, everything is a miracle … there is no transcendent master, which is why I think we have to read Christ as a repetition of Job. What dies on the cross with Christ? What dies is not an earthly representative of a transcendent. What dies is precisely God as this transcendent master of the universe. What dies on the cross for me is the idea of God as the ultimate guarantee of meaning … The lesson of Christianity … of Christ … [is that] we cannot afford this withdrawal. When we are confronted with horrible things … holocaust, concentration camps or other similar catastrophes it is a little bit vulgar to say, “This only appears to us as a catastrophe because of your limited perspective, withdrawal back and you will see how it contributes to harmony, or whatever”. There is no big other! This is why I think this would be a kind of more materialist reading why Christ truly sacrificed himself. The message is “All we can do is here”; there is no father up there who takes care of it … It is not “Trust God”. No. God trusts us. All that can be done, we should do it. In this sense, with this incomplete notion of reality, … it opens up the space for freedom. There is freedom only in an ontologically unfinished reality’.

Commenting on Job’s three theological friends, Slavoj Žižek contends that ‘God is the only true materialist … [God] comes and says there is no transcendent meaning, everything is a miracle … there is no transcendent master, which is why I think we have to read Christ as a repetition of Job. What dies on the cross with Christ? What dies is not an earthly representative of a transcendent. What dies is precisely God as this transcendent master of the universe. What dies on the cross for me is the idea of God as the ultimate guarantee of meaning … The lesson of Christianity … of Christ … [is that] we cannot afford this withdrawal. When we are confronted with horrible things … holocaust, concentration camps or other similar catastrophes it is a little bit vulgar to say, “This only appears to us as a catastrophe because of your limited perspective, withdrawal back and you will see how it contributes to harmony, or whatever”. There is no big other! This is why I think this would be a kind of more materialist reading why Christ truly sacrificed himself. The message is “All we can do is here”; there is no father up there who takes care of it … It is not “Trust God”. No. God trusts us. All that can be done, we should do it. In this sense, with this incomplete notion of reality, … it opens up the space for freedom. There is freedom only in an ontologically unfinished reality’.

While I generally do find Žižek to be a really stimulating thinker, what I find most disturbing here in this particular presentation is his notion of authority and freedom. To be sure, he never seems to challenge the relative need of authority in the area of sociality. However, if I have heard him correctly (and it’s a genuine ‘if’ on my part) when he comes to the purlieus of belief, of faith, the assumption is that we must abandon authority. It is at this point (though not at this point alone) that he so clearly betrays a failure to understand what constitutes a Christian notion of authority. For Žižek, authority is not a power but a force, a coercive burden to be shaken off rather than a love and true freedom to live in. Employing Forsyth here, I want to suggest that Žižek’s notion of authority is not ‘the source of liberty, but its load. It is something which sooner or later must produce impatience and not bring peace. It is something to be renounced as men pass to spiritual maturity. The more spiritual they consider themselves, the less they like to feel, think, or speak of authority’. There is no sense in Žižek’s notion of authority of one who employs his authority to set people – indeed his enemies – free.

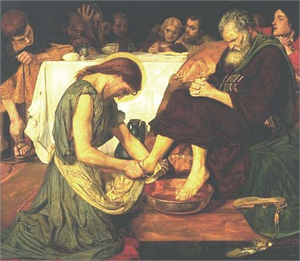

Truly, ‘God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God’ (1 Cor 1:28). This one who though he was in the form of God became the ‘low and despised’ one taught us that ‘whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many’ (Mark 10:43-45).

Truly, ‘God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God’ (1 Cor 1:28). This one who though he was in the form of God became the ‘low and despised’ one taught us that ‘whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many’ (Mark 10:43-45).

In this alone is true creaturely freedom. To assert, a Žižek does, that freedom exists ‘only in an ontologically unfinished reality’ is to deny the incarnation of God into our world, and the (cruci)-form that such authority takes. There is no greater freedom than to live under true authority. This is our gifted freedom. If God is creator, not merely in the sense of being the one who began all things but also in the decisive sense of being one who sustains all things from moment to moment by his gracious will then we must confess that no freedom exists apart from him. As C. Stephen Evans notes in his delightful book, Kierkegaard’s Fragments and Postscript: The Religious Philosophy of Johannes Climacus, ‘Because of God man is something; he is in fact a nobel something, created for eternal life with God. But his nobility lies precisely in his ability freely to recognize or fail to recognize his dependence on God. This freedom means that man is to an extent independent of God. But even his independence is itself dependent upon God’s creative power, most properly used when man recognizes – freely – his dependence’. (p. 170)

(If I have read Žižek incorrectly here, I apologise. Please take this as an invitation to help me try and understand this important thinker rightly on this point.)

As I read Zizek — and I strongly disagree with him in some of his claims here, without dismissing his points entirely — what he sees the cross as denying is an overarching Symbolic reality (‘big Other’ in Lacanian terminology) that secures the meaning of every event that occurs. As he sees it, the cross overturns the myth that every event finds its meaning within some universal equation. The cross reveals that reality can never be reduced to a ‘whole’. There is always the excess or the surd that defies definition, precluding any totalizing ‘big Other’.

For Zizek, the cross reveals that there is no transcendent Power overruling all events and securing their place within a Totality of the divine purpose. There is no hidden unifying Reality underlying the discord of history. Reality — to which God also belongs — itself is discordant and incomplete. For this reason, Christianity propels us into engagement in history.

I think that there is an important measure of truth in what Zizek is saying here. The idea of God as the ‘big Other’ who secures all meaning certainly needs to be reconceived in light of the cross, as does the notion of divine transcendence. However, I do not believe that they should be so lightly dismissed.

LikeLike

Hi, Its John from Melbourne.

Why do you take a thorough-going completely dismal materialist so seriously?

LikeLike

What is the source of the Zhizhek passage?

LikeLike

My previous response was poorly worded: the ‘light dismissal’ that I was referring to was Zizek’s treatment of the idea of God as ‘big Other’ and of the notion of divine transcendence. I think that both the concepts of divine transcendence and a God who secures meaning for the creation can be preserved, despite Zizek’s criticisms.

I think that the point that you raise about Christ’s self-definition of his mission is an important one. Zizek’s point is quite different from those made by the NT. I would be inclined to try to show how Christianity can sustain a notion of transcendence without succombing to the logic of the whole. Creation is a gift of grace and grace cannot be understood in terms of the logic of the whole. Grace must be understood in terms of excess and superabundance. The idea of a transcendent symbolic unity within which everything is meaningful, without any surds, fails to take full account of the gift-character of

reality. If creation is a gift, it finds its meaning, not within itself, nor even within a greater whole that comprehends it, but outside of itself, as it is related to the Giver.

The meaninglessness of evil is the result of its rendering creation as a thing in itself, alienating it from the giving God. The death of Christ overcomes evil by restoring the relationship between God and creation. Far from destroying the transcendent God, the cross is the opening up of creation to the transcendent. In Christ the Father gives himself completely to the creation and in Christ the creation is entirely given up to the Father. By restoring the creation in the gift economy of the Trinity it is preserved from death. The freedom of creation is secured by the difference between the gift and the giver,

a difference finally grounded on the fact that the Father is not the Son and the Son is not the Father. All of Zizioulas’ insights about Christianity’s rejection of an ontological monism should come into play here.

Transcendence is then that which encounters us everywhere in the creation as the overflowing grace of God, without dissolving creation into a greater whole. Creation is suspended from the being of God and is nothing in itself. I believe that such an approach to transcendence and creation as gift can save us from a totalitarian and ‘closed’ ontology. The disharmonies of fallen creation can be taken seriously as opposed to the transcendent. There is transcendence, but creation is not a part of a transcendent whole, but is rather that within which the transcendent God is known in the events of self-gift and consequent communion.

Such a notion of transcendence is beyond presence and absence and can lead to a form of materialism. It teaches us that transcendence is not to be found in a ‘whole’ of which the creation finds its meaning as a part (e.g. a comprehensive divine decree). Transcendence is rather known through the encountering of the Giver in his gifts, no more so than in his Son Jesus Christ. This then challenges us to reengage with the created order, as the created order is the only place where transcendence is to be encountered. By labouring to offer up the creation to the Father in his Son, we bring our reality — which is truly fragmented, not just apparently — back into relationship with the transcendent.

Freedom in creation is the freedom established by communion. An ontology of communion is quite different from a closed ontology. However, all of this need not lead to open theism, or other such positions, simply because communion is not a third term that mediates between God and the creation, but is creation’s participation in the Son’s communion with the Father in the eternal Spirit. Our freedom is a participation in God’s freedom.

LikeLike

John,

I think that Zizek needs to be taken seriously for a number of reasons. Although not a Christian, he treats the Christian faith very seriously and as a position that merits serious engagement. Such people are worth dialoguing with, even though we will strongly disagree with much that they say.

Zizek is also very gifted at showing where certain ideas can take you. Consequently, he is able to see and articulate some of the philosophical and psychological implications of Christianity with a degree of clarity that few Christians possess. Furthermore, even when I disagree with Zizek (which I frequently end up doing), he raises helpful questions about what I believe and challenges me to sharpen my understanding of the Christian faith that I profess.

LikeLike

The sources for Zizek’s thought on Christianity can be found in his two books: The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity and The Fragile Absolute: Why the Christian Legacy is Worth Fighting For. His ideas also appear in a debate with the theologian John Milbank in The Monstrosity of Christ. I am an ex-Christian who has become an atheist and I follow Zizek’s thought on Christianity as understood in the tradition of German dialectical philosophy starting with Kant through Hegel and then on into Ernst Bloch (see his book Atheism in Christianity. As my own personal devolving of my faith through the black hole of experiencing American Christian culture and the linguistic and cognitive contortions of theology and Christian pseudo-psychology (I am a therapist and writer), Zizek’s angle makes perfect sense to me in terms of having accepted God as thought construct and mythic/literary metaphor, the death of Christ on the cross is death of God that allows space for freedom of a community to be truly revolutionary in its acting out of radical engagement with the other of the neighbor rather than relying on the crutch of the Big Other of God. Zizek’s critique of the stuckness of left and right, conservative and liberal is the dialectical alternative to “squeeze out” through the middle of these distorted positions that can never be truly contacted in their pure essence. It becomes the “middle way” alternative, if you will, of allowing the boiling of the circumstances to push between to a new and truly revolutionary solution that is neither left or right (probably a little more left of centrist) to fully internalize what the essence of the Christian legacy has to offer which is a human morality that acts to be with, engage with (and by this I think Zizek means influence and be influenced) by the other of our neighbor (in the radical sense of the most difficult individuals for me to interact with).

What makes Zizek’s thought both dense and provocative is two-fold: it is influenced by Hegelian dialectic (mixed with Freud and Lacan’s critique of culture) and his counter-intuitive approach. This is what throws off his atheistic and left audience who expect him to engage in more stereotyped writ. However, Zizek repudiates this as “neo-liberal manipulation of capitalism.” Zizek’s critique of the left stands on the idea of stop protesting conservatives and fundamentalists and denouncing religion as an “evil” in the Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens sense and peel away to the perverse core of the sociological heart of the Christian socialistic revolutionary community where the New Testament moves more in the direction of morality of thinking about what is noble, right, pure, lovely, and admirable and lastly the “perfecting of God’s love in loving one another.” The message of Christianity for Zizek is: “God became man so man could become God and so that man could finally become man.” You might also find it helpful to read the review of his Puppet and Dwarf book below since it very pithily and succinctly sums up his thought.

http://www.readysteadybook.com/BookReview.aspx?isbn=0262740257

LikeLike