Today’s London Review of Books includes a provocative and challenging (for all who value democracy) essay by Slovenian sociologist, philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Žižek entitled ‘Resistance Is Surrender’. I reproduce it here:

One of the clearest lessons of the last few decades is that capitalism is indestructible. Marx compared it to a vampire, and one of the salient points of comparison now appears to be that vampires always rise up again after being stabbed to death. Even Mao’s attempt, in the Cultural Revolution, to wipe out the traces of capitalism, ended up in its triumphant return.

Today’s Left reacts in a wide variety of ways to the hegemony of global capitalism and its political supplement, liberal democracy. It might, for example, accept the hegemony, but continue to fight for reform within its rules (this is Third Way social democracy).

Or, it accepts that the hegemony is here to stay, but should nonetheless be resisted from its ‘interstices’.

Or, it accepts the futility of all struggle, since the hegemony is so all-encompassing that nothing can really be done except wait for an outburst of ‘divine violence’ – a revolutionary version of Heidegger’s ‘only God can save us.’

Or, it recognises the temporary futility of the struggle. In today’s triumph of global capitalism, the argument goes, true resistance is not possible, so all we can do till the revolutionary spirit of the global working class is renewed is defend what remains of the welfare state, confronting those in power with demands we know they cannot fulfil, and otherwise withdraw into cultural studies, where one can quietly pursue the work of criticism.

Or, it emphasises the fact that the problem is a more fundamental one, that global capitalism is ultimately an effect of the underlying principles of technology or ‘instrumental reason’.

Or, it posits that one can undermine global capitalism and state power, not by directly attacking them, but by refocusing the field of struggle on everyday practices, where one can ‘build a new world’; in this way, the foundations of the power of capital and the state will be gradually undermined, and, at some point, the state will collapse (the exemplar of this approach is the Zapatista movement).

Or, it takes the ‘postmodern’ route, shifting the accent from anti-capitalist struggle to the multiple forms of politico-ideological struggle for hegemony, emphasising the importance of discursive re-articulation.

Or, it wagers that one can repeat at the postmodern level the classical Marxist gesture of enacting the ‘determinate negation’ of capitalism: with today’s rise of ‘cognitive work’, the contradiction between social production and capitalist relations has become starker than ever, rendering possible for the first time ‘absolute democracy’ (this would be Hardt and Negri’s position).

These positions are not presented as a way of avoiding some ‘true’ radical Left politics – what they are trying to get around is, indeed, the lack of such a position. This defeat of the Left is not the whole story of the last thirty years, however. There is another, no less surprising, lesson to be learned from the Chinese Communists’ presiding over arguably the most explosive development of capitalism in history, and from the growth of West European Third Way social democracy. It is, in short: we can do it better. In the UK, the Thatcher revolution was, at the time, chaotic and impulsive, marked by unpredictable contingencies. It was Tony Blair who was able to institutionalise it, or, in Hegel’s terms, to raise (what first appeared as) a contingency, a historical accident, into a necessity. Thatcher wasn’t a Thatcherite, she was merely herself; it was Blair (more than Major) who truly gave form to Thatcherism.

The response of some critics on the postmodern Left to this predicament is to call for a new politics of resistance. Those who still insist on fighting state power, let alone seizing it, are accused of remaining stuck within the ‘old paradigm’: the task today, their critics say, is to resist state power by withdrawing from its terrain and creating new spaces outside its control. This is, of course, the obverse of accepting the triumph of capitalism. The politics of resistance is nothing but the moralising supplement to a Third Way Left.

Simon Critchley’s recent book, Infinitely Demanding, is an almost perfect embodiment of this position. For Critchley, the liberal-democratic state is here to stay. Attempts to abolish the state failed miserably; consequently, the new politics has to be located at a distance from it: anti-war movements, ecological organisations, groups protesting against racist or sexist abuses, and other forms of local self-organisation. It must be a politics of resistance to the state, of bombarding the state with impossible demands, of denouncing the limitations of state mechanisms. The main argument for conducting the politics of resistance at a distance from the state hinges on the ethical dimension of the ‘infinitely demanding’ call for justice: no state can heed this call, since its ultimate goal is the ‘real-political’ one of ensuring its own reproduction (its economic growth, public safety, etc). ‘Of course,’ Critchley writes,

‘history is habitually written by the people with the guns and sticks and one cannot expect to defeat them with mocking satire and feather dusters. Yet, as the history of ultra-leftist active nihilism eloquently shows, one is lost the moment one picks up the guns and sticks. Anarchic political resistance should not seek to mimic and mirror the archic violent sovereignty it opposes’.

So what should, say, the US Democrats do? Stop competing for state power and withdraw to the interstices of the state, leaving state power to the Republicans and start a campaign of anarchic resistance to it? And what would Critchley do if he were facing an adversary like Hitler? Surely in such a case one should ‘mimic and mirror the archic violent sovereignty’ one opposes? Shouldn’t the Left draw a distinction between the circumstances in which one would resort to violence in confronting the state, and those in which all one can and should do is use ‘mocking satire and feather dusters’? The ambiguity of Critchley’s position resides in a strange non sequitur: if the state is here to stay, if it is impossible to abolish it (or capitalism), why retreat from it? Why not act with(in) the state? Why not accept the basic premise of the Third Way? Why limit oneself to a politics which, as Critchley puts it, ‘calls the state into question and calls the established order to account, not in order to do away with the state, desirable though that might well be in some utopian sense, but in order to better it or attenuate its malicious effect’?

These words simply demonstrate that today’s liberal-democratic state and the dream of an ‘infinitely demanding’ anarchic politics exist in a relationship of mutual parasitism: anarchic agents do the ethical thinking, and the state does the work of running and regulating society. Critchley’s anarchic ethico-political agent acts like a superego, comfortably bombarding the state with demands; and the more the state tries to satisfy these demands, the more guilty it is seen to be. In compliance with this logic, the anarchic agents focus their protest not on open dictatorships, but on the hypocrisy of liberal democracies, who are accused of betraying their own professed principles.

The big demonstrations in London and Washington against the US attack on Iraq a few years ago offer an exemplary case of this strange symbiotic relationship between power and resistance. Their paradoxical outcome was that both sides were satisfied. The protesters saved their beautiful souls: they made it clear that they don’t agree with the government’s policy on Iraq. Those in power calmly accepted it, even profited from it: not only did the protests in no way prevent the already-made decision to attack Iraq; they also served to legitimise it. Thus George Bush’s reaction to mass demonstrations protesting his visit to London, in effect: ‘You see, this is what we are fighting for, so that what people are doing here – protesting against their government policy – will be possible also in Iraq!’

It is striking that the course on which Hugo Chávez has embarked since 2006 is the exact opposite of the one chosen by the postmodern Left: far from resisting state power, he grabbed it (first by an attempted coup, then democratically), ruthlessly using the Venezuelan state apparatuses to promote his goals. Furthermore, he is militarising the barrios, and organising the training of armed units there. And, the ultimate scare: now that he is feeling the economic effects of capital’s ‘resistance’ to his rule (temporary shortages of some goods in the state-subsidised supermarkets), he has announced plans to consolidate the 24 parties that support him into a single party. Even some of his allies are sceptical about this move: will it come at the expense of the popular movements that have given the Venezuelan revolution its élan? However, this choice, though risky, should be fully endorsed: the task is to make the new party function not as a typical state socialist (or Peronist) party, but as a vehicle for the mobilisation of new forms of politics (like the grass roots slum committees). What should we say to someone like Chávez? ‘No, do not grab state power, just withdraw, leave the state and the current situation in place’? Chávez is often dismissed as a clown – but wouldn’t such a withdrawal just reduce him to a version of Subcomandante Marcos, whom many Mexican leftists now refer to as ‘Subcomediante Marcos’? Today, it is the great capitalists – Bill Gates, corporate polluters, fox hunters – who ‘resist’ the state.

The lesson here is that the truly subversive thing is not to insist on ‘infinite’ demands we know those in power cannot fulfil. Since they know that we know it, such an ‘infinitely demanding’ attitude presents no problem for those in power: ‘So wonderful that, with your critical demands, you remind us what kind of world we would all like to live in. Unfortunately, we live in the real world, where we have to make do with what is possible.’ The thing to do is, on the contrary, to bombard those in power with strategically well-selected, precise, finite demands, which can’t be met with the same excuse.

The Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities has been hosting some ‘Masterclasses’ with Slavoj Žižek. The three talks are available for download here:

The Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities has been hosting some ‘Masterclasses’ with Slavoj Žižek. The three talks are available for download here:

When were you happiest?

When were you happiest?

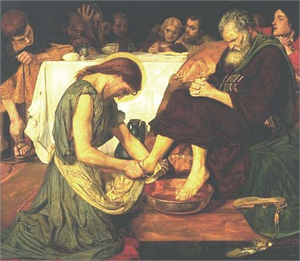

Commenting on Job’s three theological friends, Slavoj Žižek contends that ‘God is the only true materialist … [God] comes and says there is no transcendent meaning, everything is a miracle … there is no transcendent master, which is why I think we have to read Christ as a repetition of Job. What dies on the cross with Christ? What dies is not an earthly representative of a transcendent. What dies is precisely God as this transcendent master of the universe. What dies on the cross for me is the idea of God as the ultimate guarantee of meaning … The lesson of Christianity … of Christ … [is that] we cannot afford this withdrawal. When we are confronted with horrible things … holocaust, concentration camps or other similar catastrophes it is a little bit vulgar to say, “This only appears to us as a catastrophe because of your limited perspective, withdrawal back and you will see how it contributes to harmony, or whatever”. There is no big other! This is why I think this would be a kind of more materialist reading why Christ truly sacrificed himself. The message is “All we can do is here”; there is no father up there who takes care of it … It is not “Trust God”. No. God trusts us. All that can be done, we should do it. In this sense, with this incomplete notion of reality, … it opens up the space for freedom. There is freedom only in an ontologically unfinished reality’.

Commenting on Job’s three theological friends, Slavoj Žižek contends that ‘God is the only true materialist … [God] comes and says there is no transcendent meaning, everything is a miracle … there is no transcendent master, which is why I think we have to read Christ as a repetition of Job. What dies on the cross with Christ? What dies is not an earthly representative of a transcendent. What dies is precisely God as this transcendent master of the universe. What dies on the cross for me is the idea of God as the ultimate guarantee of meaning … The lesson of Christianity … of Christ … [is that] we cannot afford this withdrawal. When we are confronted with horrible things … holocaust, concentration camps or other similar catastrophes it is a little bit vulgar to say, “This only appears to us as a catastrophe because of your limited perspective, withdrawal back and you will see how it contributes to harmony, or whatever”. There is no big other! This is why I think this would be a kind of more materialist reading why Christ truly sacrificed himself. The message is “All we can do is here”; there is no father up there who takes care of it … It is not “Trust God”. No. God trusts us. All that can be done, we should do it. In this sense, with this incomplete notion of reality, … it opens up the space for freedom. There is freedom only in an ontologically unfinished reality’. Truly, ‘God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God’ (1 Cor 1:28). This one who though he was in the form of God became the ‘low and despised’ one taught us that ‘whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many’ (Mark 10:43-45).

Truly, ‘God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God’ (1 Cor 1:28). This one who though he was in the form of God became the ‘low and despised’ one taught us that ‘whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave, even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many’ (Mark 10:43-45).