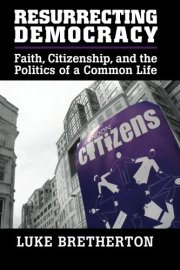

I’ve just finished re-reading Luke Bretherton’s wonderful – and very timely – book, Resurrecting Democracy: Faith, Citizenship, and the Politics of a Common Life. I’ll be drawing upon it for a paper that I’ll be giving in Chile later this year. Along the way, I’ve been reflecting on these sentences in light of the deeply-troubling events taking place at various US borders:

I’ve just finished re-reading Luke Bretherton’s wonderful – and very timely – book, Resurrecting Democracy: Faith, Citizenship, and the Politics of a Common Life. I’ll be drawing upon it for a paper that I’ll be giving in Chile later this year. Along the way, I’ve been reflecting on these sentences in light of the deeply-troubling events taking place at various US borders:

When everything is treated as a crisis or an exception, crisis and disorder become means of governing.

Framing something as an exception justifies two parallel responses. The first is the closing down of due process, proper accountability, and collective self-rule: the crisis demands immediate action rather than taking the time to formulate reasoned and collective political judgments. The second is to claim the problems are so overwhelming and so urgent that they are beyond the scope of widespread deliberation and human judgment and instead a “neutral,” topdown procedure must be found to address the crisis. This can involve leaving it all up to the market to decide or trying to find a one-size-fits-all, technocratic, administrative solution … that just eradicate the problem in one go. This second response displays what can be seen as the modernist prejudice: the need to abandon tradition and eviscerate rather than reform existing institutions in order to inaugurate the “new,” “the modern,” or the “progressive” [– or, we might say, the “alternative” –] solution.

But what happens when the ‘exception’ is no longer true to definition but becomes the new norm, literally by the stroke or two of a pen? (I write this as news filters into my ‘alerts’ about the firing of acting Attorney General, Sally Yates.) What happens when one reads the current disorder against a narrative like this one which suggests that the ‘primary aims’ and ‘main organisational goal[s]’ of the new regime are to undermine, eliminate, and replace all existing power structures with ‘a tight inner circle’ hungry for ‘unchallenged power’? That human societies have been here before doesn’t entirely take the sting out of things, although some time reading the Hebrew Bible, for example, does at least help to see that sting in some continuity with the nature of history as shot through with the tragic and violent.

The one thing that is certain in our current political climate is that things are ‘deeply uncertain and fluid’ (Rowan Williams). The other one thing that is certain is that those in liberal democracies are embroiled in a real battle about power, and about what role, if any, the ‘existing rulebook’ (Bretherton) will play, and about the possibility of living a genuinely-shared life (with or without the hassle of all those left-leaning loopheads ‘blocking traffic and causing some travelers to miss their flights’).

The one thing that is certain in our current political climate is that things are ‘deeply uncertain and fluid’ (Rowan Williams). The other one thing that is certain is that those in liberal democracies are embroiled in a real battle about power, and about what role, if any, the ‘existing rulebook’ (Bretherton) will play, and about the possibility of living a genuinely-shared life (with or without the hassle of all those left-leaning loopheads ‘blocking traffic and causing some travelers to miss their flights’).

It is this, among other things, that makes Bretherton’s work so interesting. Drawing upon insights from Aristotle, Saul Alinsky, and others, and his own involvement with grassroots democracy expressed in the work of Citizens UK, Bretherton’s is a vision of democratic politics and of vibrant civil society expressed in what he calls ‘broad-based community organizing’ in which those of different faiths – and of non – and who carry ‘myriad obligations and commitments’ and identities and practices, coordinate, negotiate, and seek to forge a common life, a life that will inevitably call into question the kind of arrangements designed to leave economic and political and ecclesiastical elites immune from accountability and responsible participation in a common social, economic, and political space. Bretherton recognises that ‘whereas the medieval city offered one set of political opportunities and challenges, the modern and now world city offers an assemblage of material and social conditions for a different set’. And rather than shy away from this reality, or rage against it, Bretherton leans into its opportunities:

What community organizing represents is a means of reconstituting, from the ground up, a sensus communis, which can then form the basis of a practical rationality on which shared judgments can be made. It does this through assembling a ‘middle ground’ out of the existing traditions, customs, and habits that have poured into the city. The practices of community organizing create the conditions through which a shared world of meaning and action can emerge – albeit one often based on partial misunderstandings and misconceptions.

Such efforts towards a sensus communis are not without opposition however, as anyone who has been involved in grassroots democratic movements can testify :

Whether on the Left or the Right, those who would seek to do without a shared life and resort instead to technical, bureaucratic, legal, and market-based procedures of control and risk avoidance consistently oppose organizing and thence the creation of a middle ground.

So goes what Bretherton calls ‘the virtuous pursuit of democratic politics’.

Apathy leads to all kinds of death. ‘The body politic is a constructed, fractious, and fragile artifice that requires something like the practices of community organizing in order to constitute and reconstitute it out of its disparate elements. It is a constant work in progress rather than a spontaneous, natural phenomenon’ (Bretherton).

[Image: Verso]

Funny you should post this today. The theology book discussion group (via skype) that I am in discussed this book last night. It is a really useful book. Would you be interested in joining a skype group that discusses books in theology and social theory mainly?

LikeLike

I think the American public is experiencing a sort of cognitive dissonance as they attempt to identity the rationale behind the administration’s actions when that rational may not even exist. I really liked your point about the sensus communis! It was a very meaningful extrapolation of current events.

LikeLike

Cf. these concluding remarks by Rowan Williams in a refection entitled “Mass democracy has failed — it’s time to seek a humane alternative” (written shortly after Trump’s election victory):

“… Naught for our comfort; but at least an opportunity to ask how politics can be set free from the deadly polarity between empty theatrics and corrupt, complacent plutocracy. What will it take to reacquaint people with control over their communities, shared and realistic values, patience with difference and confidence in their capacity for intelligent negotiation? It’s the opposite of what Trump has appealed to. The question is whether the appalling clarity of this opposition can wake us to work harder for an authentic and humane politics that seems in such short supply

LikeLiked by 1 person

@Bruce: it’s encouraging to learn that you are part of the group discussion around this book. I might be interested in being part of that discussion. Email me the details.

@NKP: I think that you’re right about the cognitive dissonance thing.

@Kim: yeah, great piece by Williams. It’s one of 2–3 bits of writing from him that I’ll be referring to in my paper. There’s also some very helpful material in his Faith in the Public Square.

LikeLike